I was fortunate to have these two F.X. Tourte cello bows on my bench together, both made – in my view – at very much the same time, around 1820. Interestingly, while they share very close technical similarities in their proportions and working mannerisms, at the same time we can see a stylistic freehand at work.

These are both late ‘golden period’ cello bows displaying all the classic Tourte attributes: octagonal sticks; rugged hatchet head forms; silver head-plates; and beautifully proportioned frogs and buttons. Looking in more detail, we can observe the very close similarities in the internal workings of the frogs and of the head mortices.

The sticks

The sticks are made from a choice of pernambuco that permitted Tourte to arrive at an ideal balance between strength and flexibility. I believe that he was extremely sensitive to this essential ratio and would have determined – in the stick-making process – the amount of wood to remove (the graduation of the stick) purely by feel. In all but a very few number of Tourte bows that I have examined, there has always been a certain flexibility in the sticks, mitigated by a resilience that makes sure that the stick won’t give in. It is this consistent, almost-magical formula that made Tourte the desirable ‘go to’ bow maker, acclaimed by musicians from his own day to the present.

Both of these sticks are of an asymmetric octagonal section, which was the norm throughout Tourte’s golden period (c. 1800–1820). Prior to 1800 the vast majority of his sticks were round; in the later years, some round-form sticks were made again.

The heads

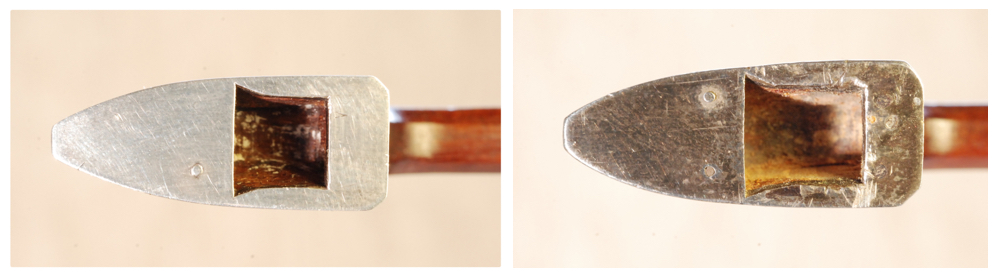

In the heads we can see Tourte’s freedom of style, expressed through the variations in the profiles: the back of the head of bow 1 (pictured left in all the images) is slightly rounder as it turns into the stick; bow 1 also is shorter (across the width of the head plate) than bow 2 by 1.5 mm, yet both bows appear to be harmonious in their respective proportions. The crown of the stick – where it turns into the ridge – of bow 1 is softer and slightly more rounded than that of bow 2, yet these tiny variations are nonetheless significant in how the whole of each head appears to the eye.

The ridges of these two bows follow almost exactly the same line, deviating to the left towards the bottom (from above), then centering up just as they meet the silver point. I am of the opinion that this typical deviation from a straight line that is nearly always seen in Tourte’s bows is a result of a quirk of hand, rather than an aesthetic consideration. The position of the deviations changed over the years from at times being quite straight in the early days, to examples in the last years where the ridge line moves to the right.

The mortices of these two bows, although of differing lengths, are of a very similar character.

Both mortices are nearly parallel in width until shortly before the front, where they suddenly widen out. The ‘wall’ at the front of these mortices is cut quite forward.

This is a classic form of an F.X. Tourte head mortice: by cutting forward (and also slightly back, at the opposite end of the mortice), space is created for the hair knot without the need to cut down too deeply.

The frogs

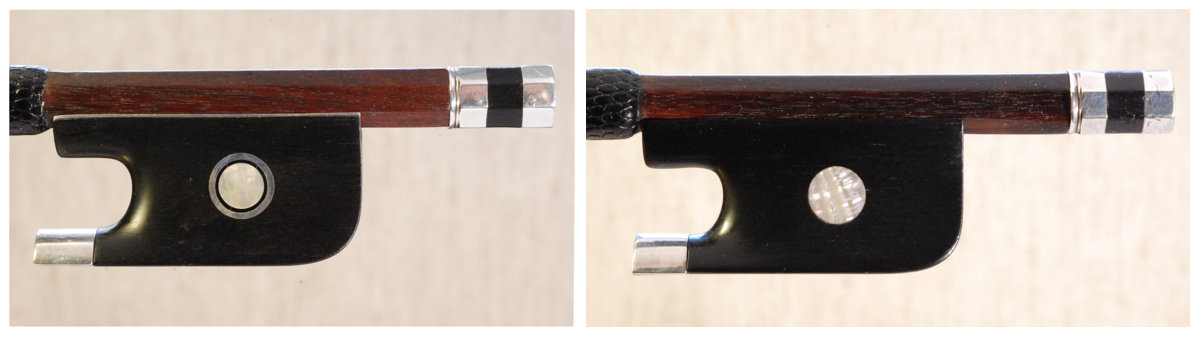

The forms of the throats are quite different, as is immediately obvious (the silver underside on bow 1 is a later addition).

As with the overall form of the head, it is in the throat of the frog that we can see the freehand artistry of the maker. Bow 1 has a slightly more open throat, the curves being quite gentle and even; the length of the frog (at the ferrule) extends noticeably beyond the length at the thumb-projection. Bow 2 shows somewhat more complex contouring (and in this throat in particular, we can see the influence that Tourte exerted on Dominique Peccatte).

The choice of the ‘Parisian eye’ or the plain pearl eye would seem to be purely aesthetic. Throughout his career, Tourte would use the three-piece model of button with either Parisian eye or pearl-eye decorated frogs (aside from a few examples of one-piece buttons in the very early works).

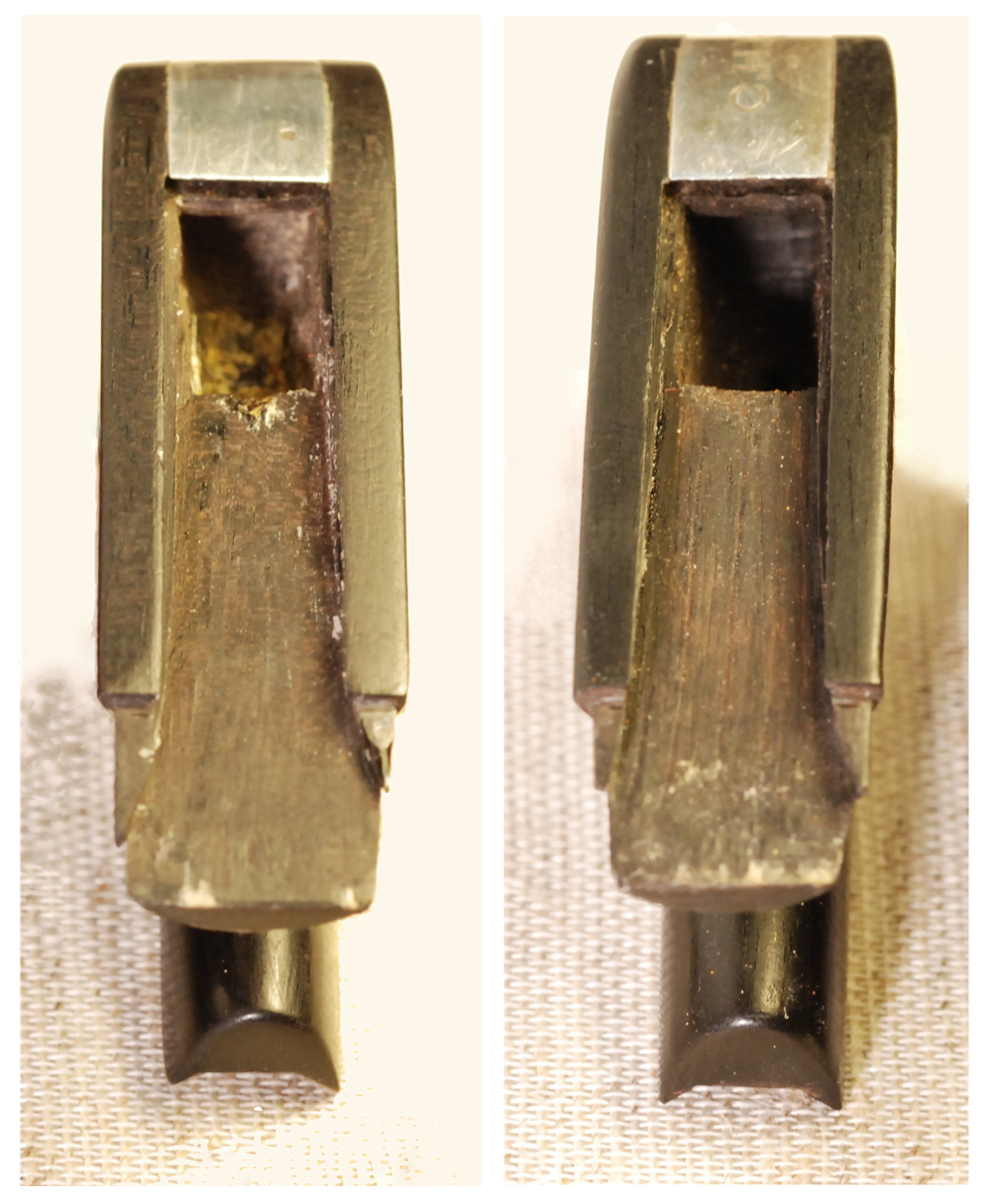

Looking at some of the structural details of the frog and button, you will see why I consider these two bows to have been made very much at the same period.

The proportions of all of the parts are very close to each other: the width of the frog, the length and shape of the ferrule; the length of the pearl slide; the width of the back-plate; and the position of the pins.

Internally, the workings of these two frogs are almost identical. The back-plates stop just above the back of the mortices; the hair channels are rather shallow and, to allow for more space for the hair, the walls of the channels are undercut.

The tongue (or ‘ferrule support’) on both of these frogs clearly shows the tool that was used in order to form the ebony to fit the ferrule: a rather coarse file!

The curve of the ferrule back is almost identical in both of these examples.

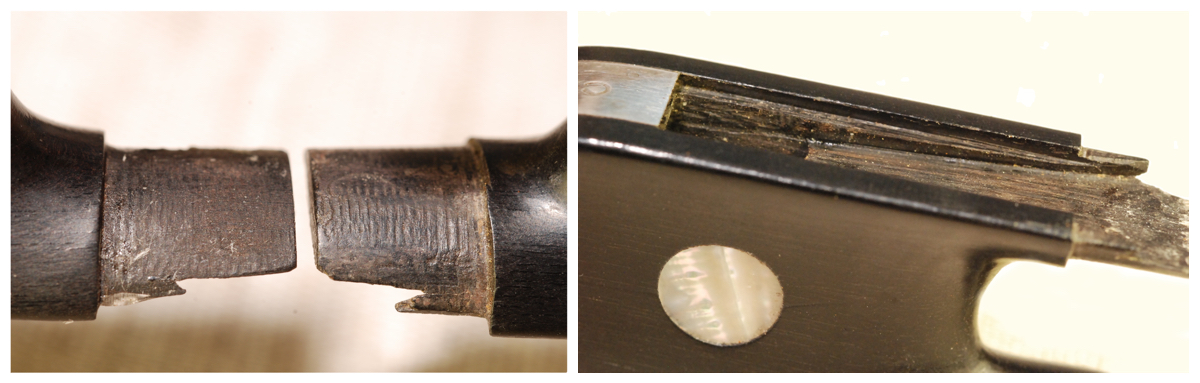

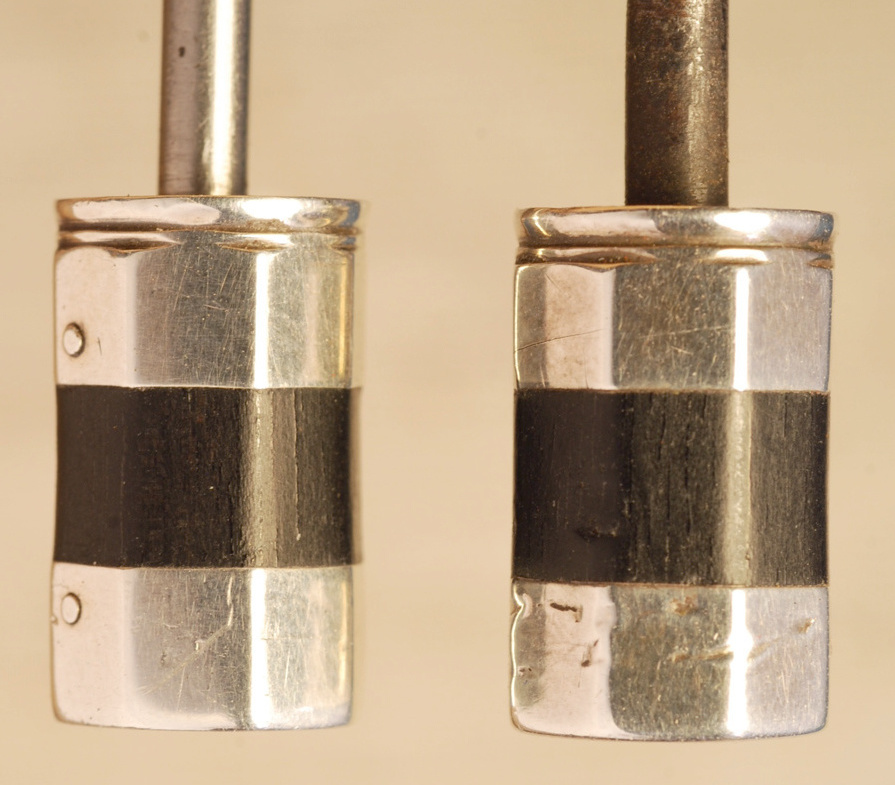

The buttons

Finally, with a look at the buttons of these two bows, we can see how consistent Tourte was in his design. (The shaft of the button on the left is not original.) The mouldings (or collars) are exactly the same in concept: note how the second, smaller collar has been slightly yet deliberately filed into, creating a pleasing transition between the flat facets and the fully rounded front collar. The proportions of the silver rings and the ebony body are beautifully balanced in both cases.

In Tourte’s cello bows, we can find the greatest variety of form – particularly in the design of the heads. This variety ranges from the ‘violin head’ models (which really are upright, blown-up versions of his violin bows) to hatchet heads that are even more rugged and exaggerated than the two examples illustrated here. In between those extremes are ‘swan-heads’ (with rounded backs to the heads), models that could be described as violin/hatchet heads (somewhere in between the two) and others that are still considered today to be the most perfectly formed classic bow heads. What is perhaps extraordinary about all these variants is that if one encounters a hitherto unknown model by F.X. Tourte, there will, from a combination of all the aspects that he created, be something about it that will leave you in no doubt of its authorship.

Peter Oxley is a bow maker and expert.

The cello bow illustrated on the left is currently for sale privately by Tarisio. To make an enquiry, please contact Matthew Huber, mhuber@tarisio.com.