When one mentions the Hill Collection at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the mind immediately flies to the ‘Messie’. However, the ‘Messie’ is only one part of a collection rich in treasures and opportunities to expand our understanding of the violin making craft and its great exponents. This holds true for the bows as well. Three early bows, catalogued as Ash. 27–29, present us with a case study of the evolution of early bow making in England in the 18th century.

When one examines the style and finish of their heads, the manner of fluting on their sticks and the style and finish of their frogs, it becomes increasingly clear that they are all from the same hand. This hand would once have been called Edward Dodd, but research over the years has made it clear that such bows were all crafted decades before the Dodd family even arrived in London. While their maker might remain anonymous, these particular bows were closely connected with some of the premiere London shops of that age.

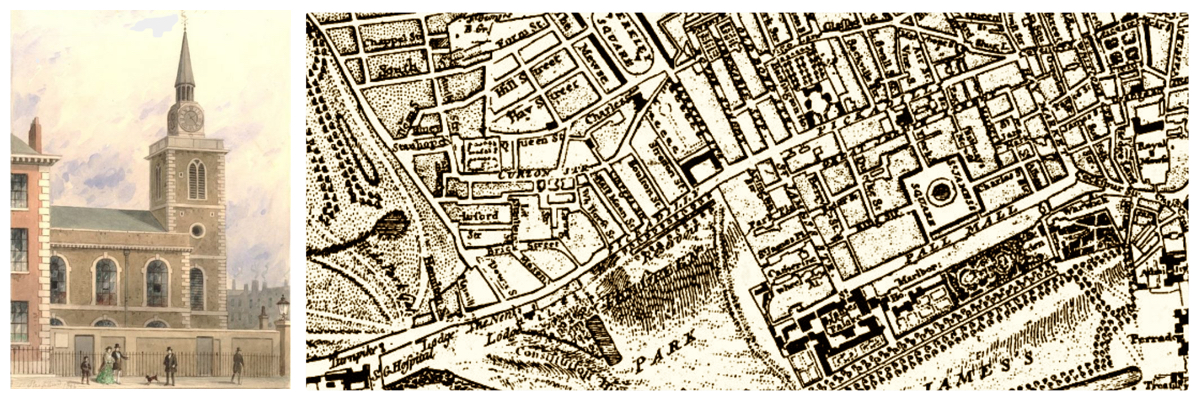

St James Piccadilly (left), near to which Peter Wamsley’s shop, the Harp and Hautboy, was located. John Rocque’s map of London (right) shows Piccadilly in the 1740s, around the time of Wamsley’s death in 1744

The first and earliest bow, Ash. 27, is also the simplest, with fluting just at the part of the handle where the player would grasp it as well as along the upper surfaces of the head. The stick itself is substantially straight, but with an outward curve towards the head. As was the case with most early bows, the hair was inserted into mortises in both the head and the heel. The frog of this example is a later replacement, but the original must have been very similar in concept: it is clipped below the hair, its pointed nose setting securely into a small indentation cut for that purpose. This method allowed for the hair to be tightened at the moment of use, although the tension was restricted to one setting as the hair length could not be easily altered. Channels along the back and lower surfaces of the frog held the hair in place and prevented its slipping off. This bow is generally dated to the decade of the 1720s.

Ash. 27, an unbranded English bow from the 1720s. Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

With Ash. 28, which is generally attributed to the decade of the 1740s, we have something very similar but significantly different. For one thing, it is the earliest brand one encounters in an English bow. This is a valuable tool in applying an accurate date to the bow. Peter Wamsley (c. 1670–1744), the dealer for whom it was made, was the preeminent violin maker in London during the years after Barak Norman and Daniel Parker. His shop ran from the beginning of the 18th century until his death in 1744, and was kept open by his widow and son for another seven years thereafter. Such was his ability that he received a Royal Warrant as violin maker to the Prince of Wales. The bow bears the brand ‘WAMSLEY’ prominently stamped in the center of both sides of the frog. Since the player’s hand during this period did not grasp the frog, this kept it sharp and distinct, making it a very good device for disseminating Wamsley’s name among musicians.

As with the earlier bow, the stick is concave, especially towards the tip, but in this case the fluting on the head extends to the throat, which on the earlier bow had been left roughly finished. This could reflect its different application: 27 is a violin bow, 28 a viol or cello bow and thus much larger in proportions. Also like the earlier bow, the hair is fitted into mortises in both head and heel, but again with a refinement: the mortise in the head has small notches cut into the upper corners, allowing the hair to be spread to a wider ribbon. Similarly, the surfaces of the frog, which clips on in the same manner as the earlier bow, widen to allow a broader ribbon of hair. A further refinement is that the surface is convex, thus preventing the hair from bunching in the middle.

Ash 28, a viol or cello bow branded ‘Wamsley’ from the 1740s. Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

A curious feature of these bows is that while both appear to have buttons, neither one is functional. On the violin bow, the very end of the stick is fluted, perhaps as a decorative touch. On the viol bow, an ivory knob is glued to the back of the heel. This would find greater purpose in the third of our bows.

Ash.29 is a viola bow and thus balanced between the previous two in mass and size. It bears the brand ‘T. SMITH’ on its frog. This refers to Thomas Smith (c. 1725–1789), who worked for Wamsley during his last years and who acquired the business from his widow in 1751. Smith had a similar reputation and celebrity to Wamsley, as he retained the Royal Warrant to become violin maker to both George III and the Prince of York, remaining so until his death in 1789. It is the latest of the three, thought to date from around 1755.

The greatest change and refinement of the Smith bow is the use of a screw adjustment, the earliest known among English bows. The frog, while modeled after the earlier ones, no longer clips into place; its pointed leading edge now can slide smoothly along the stick. The fluting of the stick runs over the entire heel, and the top surface of the frog has been fluted to match, resulting in a stable contact that does not wobble.

Ash 29, a viola bow branded ‘T. Smith’, c. 1755. Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The hair is now set into a mortise cut into the bottom surface of the frog and runs along a convex channel just at the very end of its contact with the frog. In the head, the cut notches of its mortise are formalized into the classic and familiar T-mortise, with larger and more regular cutaways at the upper corners of the mortise.

As for adjusting the hair, the bow now has a channel cut through the center of the heel, allowing a worm screw to be inserted. A matching eyelet is set into the frog and a larger mortise cut into the stick to allow the eyelet to slide both forward and backwards, in the process loosening or tightening the hair. To prevent the heel from splitting due to the resulting tension, a large nipple was cut at the end, which fit comfortably into a matching recessed hollow in the inner surface of the button.

And so, with these three bows, we have a thorough illustration of the development of the method for tightening and loosening bow hair that we still use today, and a fairly clear understanding of when this development occurred – an example of the many lessons to be learned from this wonderful collection.

Philip J. Kass is an expert on classical violin making and has contributed extensively to the Journal of the Violin Society of America, The Strad magazine and the New Grove Dictionary of Music.