The man who created Cozio.com, Philip Margolis, was right when he concluded in 2003 that the violin world needed more readily accessible information in the marketplace for instruments of the violin family and their bows. So Margolis created the largest online database for the violin world, which now provides information on over 30,000 instruments and bows. Ten years later, he remarked of his mission:

My overriding goal with the site has always been to level the playing field for buyers, especially musicians. The violin market is really about information and historically there has been a huge imbalance in the information available to dealers versus musicians. Given that information is the currency of the market, it is natural that most dealers would be opposed to efforts to expand access to this information. To a large extent, a dealer’s livelihood depends on him having more information (or higher-quality information) than his competitors and customers.

Since the launch of Cozio, there has been an explosion of other websites with an array of information relating to fine instruments and bows. From computerized tomography scans, violin varnish research, dendrochronology, violin bridges, violin string selection, information on historic violin makers, auction results, and here, the Violin Society of America’s journal, excerpts from The Strad Archive, expert commentary and here, stolen instrument databases, such as the FBI’s, museum websites and here, and online forums, the list of evolving websites is nearly boundless. This has resulted in a shift in the information paradigm for those in the violin world, democratizing access to an array of content, at times for a fee.

In the marketplace for historical instruments and bows, beyond sound, the essential topics are authenticity, provenance, valuation and condition. Analysis of these topics will likely be informed by some combination of connoisseurship, historical records and scientific forensics if the value of the instrument warrants it. Content on the internet may contribute in some measure to these topics.

Taking the topic of provenance as an example, what can one learn on the web and why is it important? Provenance is the history of ownership and possession of an object, and this information may materially contribute to an understanding of authenticity (although it does not, as is sometimes believed, equate to authenticity). Provenance also may be critical to steering clear of instruments with a tainted ownership history and potential liability; it can be useful to insurers and law enforcement on the trail of a misappropriated instrument. Evidence of provenance may be found in certificates of authenticity, correspondence, diaries, photographs, appraisals, inventories, bills of sale, repair receipts, concert programs, books, exhibition and auction records, and other materials. Markings, labels and inscriptions on and in instruments may also be relevant.

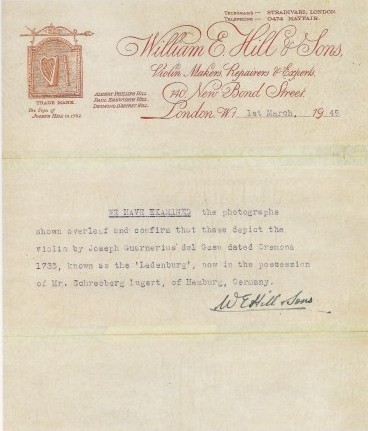

Certificates such as this 1949 Hill one are a good source of provenance information, but are not usually available online

As copyrighted works enter the public domain (and sometimes when they haven’t), they are being scanned and uploaded to the internet and many of these materials contain provenance detail. For example, the HathiTrust Digital Library has posted Wurlitzer’s 1931 collection of 17th and 18th century instruments. Tarisio was the first auction house to post certificates of authenticity, correspondence and other historical records online, and in some instances other auction websites have since adopted this practice, although generally only before the auction. For private dealer sales, historical documentation is not often placed online, but there are exceptions.

Some of the most important sources of information are proprietary violin dealer records. Occasionally these records may be found online, for example, the Musée de la Musique’s Bernardel, Caressa and Français Archive Collection, but many are not publicly available. Online debate exists regarding who should have access to such content. For example, in 2006 Philip Margolis said of historical dealer records:

[K]eeping this information private reinforces the feeling of many that the violin trade is controlled by a few heavyweights who sometimes act in their own self-interest at the expense of the general violin community, which includes researchers and musicians in addition to other dealers. It would be a great gesture, and very helpful for research purposes, if …[those] who have important historical archives, would make their private databases and documents available to the general public.

But others don’t agree, such as one violin shop owner who argued:

[T]he firms who own the information have to justify a significant expense (what it cost to obtain them), and the records were not public to begin with. They were private business records (just like those from Wurlitzer, Français, Hamma, L& H, etc.). In my opinion, it’s refreshing to know that this database is shared by some of the best experts in the field rather than horded by just one….

Similarly, an anonymous violin forum participant responded, ‘I understand why – they purchased this information as an investment into their business. The database is essentially a database of trade knowledge.’ This discussion is no longer on the original website.

Should proprietary rights to such information ever be outweighed by the public interest in disclosure of historical information? Current owners may have legitimate privacy concerns regarding their ownership when their instruments are offered for sale through auction houses and dealers. The Cozio archive has omitted current owner names for this reason. But how long is too long, if ever, to keep the provenance of an instrument confidential, when the absence of such information may leave buyers and the public with insufficient information regarding instrument histories?

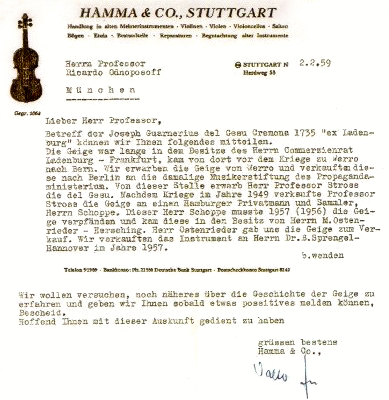

A 1959 letter from Hamma & Co. giving information about the ‘Ladenburg’ provenance

The 1735 ‘Ladenburg’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ provides an example of how far one can get by researching provenance online. Many records relating to this violin are reproduced in a 1998 monograph entitled, Joseph Guarnerius del Gesù, Cremona 1735: Ex-Ladenburg, by Machold Rare Violins. But if you don’t have access to the book, what can one glean from the web?

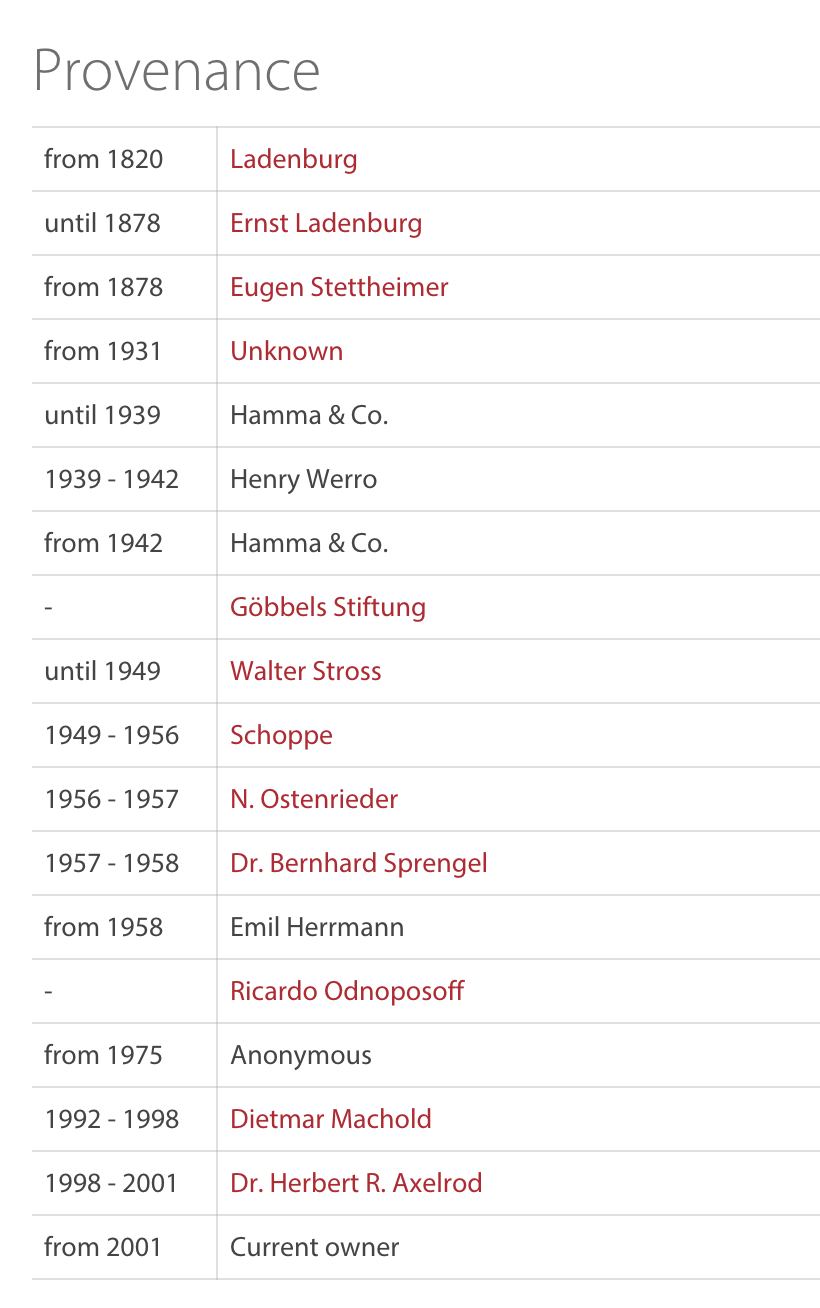

A review of the Cozio record for this instrument reveals an illustrious history, with Nicolò Paganini as one of the violin’s earliest reported players. It was owned by Ernst Ladenburg of Frankfurt from 1820 to 1878, then allegedly transferred to the Frankfurt collector Eugen Stettheimer in 1878. Also included is an excerpt from the New York Times regarding the 16 investors who purchased the violin in 2001 for use by Robert McDuffie. But there is a glaring provenance gap during the 1930s: specifically, what happened to the violin after it was owned by Stettheimer and before it came into the hands of the Stuttgart dealer Hamma & Co., who sold it in 1939? In an effort to fill this gap, what can be ascertained online?

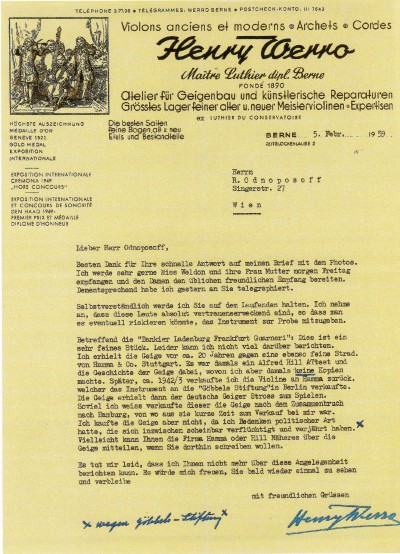

Two letters from February 1959 have been scanned and uploaded by third parties. The first letter is from Hamma and the second is from Swiss dealer Henry Werro. The original link to a scan of the Werro letter and its English translation has broken, but it can be retrieved, in part, from the internet’s archive, the Wayback Machine.

Henry Werro’s letter of 1959 regarding the ‘Ladenburg’

Werro’s letter states that he acquired the ‘Ladenburg’ from Hamma through a trade in about 1939, and that Hamma re-acquired the violin from Werro in 1942–43 and sold it to the ‘Goebbels Stiftung’ in Berlin. Werro had a chance to buy it again after the war, but declined, having temporary doubts for political reasons.

Commentary by David Schoenbaum in The Violin: A Social History of the World’s Most Versatile Instrument, W.W. Norton & Co., 2013, is also available. Schoenbaum points out: ‘There is no indication of when and how Hamma came by the instrument, or why the owner chose to sell it. But it was only a few months after the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938 led to de facto expropriation of what was left of Jewish property.’

Archival records from the Nazi era contain more than a few references to Hamma’s efforts on behalf of the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda. Such records include two spring 1944 invoices for the sale of 67 stringed instruments to the Reich Bruckner Orchestra, a subsidiary of the Reich Rundfunk, the Nazi’s National Radio Orchestra. These Hamma invoices state: ‘We sell to you in the name and by order of the Reich Ministry for Propaganda and Public Enlightenment, Berlin….’ This reference is also online.

Further information is sparse. Walter Hamma’s obituary in the October 1988 issue of The Strad magazine reported that the Hammas moved a number of fine instruments to the surrounding countryside during World War II, but that much was lost by Allied bombing in Stuttgart. Fridolin Hamma’s obituary in the December 1969 issue of The Strad stated that ‘the premises of Hamma & Co. were totally destroyed in 1944 and many valuable instruments and documents were burnt.’ These articles from The Strad archive were previously online, but are not presently accessible.

Cozio’s provenance listing for the ‘Ladenburg’

Yet some Hamma records from this era have survived. For example, Dietmar Machold, who last sold the ‘Ladenburg’, advertised online that he owned the Hamma records. This appears to have been an exaggeration, according to the new owner of the Machold documentary archive, although Machold did possess a 1931 record from the ‘Ladenburg’ file. So for the moment, online records fail to fill important gaps in the ‘Ladenburg’ Guarneri’s history. Even so, a great wealth of information regarding this instrument is available via the internet.

Has the internet made a difference to the marketplace? The answer is yes, and no. Websites, like books on the library shelf, are only as good as their author’s word. A reader must be discriminating. The online environment is transformative, transitory, flawed, dynamic and remarkable. There is no substitute on the web for true expertise. And for those who are in search of information in historical records buried in countless paper archives, public and private, serious analysis on the internet is likely to be a challenge. Still, advocates for information access, and those looking for answers, have found a hospitable landscape in the quickly changing digital age, where the unimaginable today may be commonplace tomorrow.

Carla Shapreau, a lawyer and violin maker, is on the adjunct faculty at the University of California, Berkeley. She has written on many topics relating to the arts and is co-author of ‘Violin Fraud: Deception, Forgery, Theft, and Lawsuits in England and America’, Oxford University Press.