It’s not clear why Panormo left what appears to have been a flourishing family business in Naples manufacturing mainly woodwind instruments, but he probably first arrived in Paris around 1770. The date is indicated by an interview with Panormo’s grandson, Edward Ferdinand, in the ‘Musical Opinion’ of 1888, which states that his father, Joseph, was born in Naples in 1768 and that the family moved from Paris to London in 1772. An oboe and a violin both branded ‘Vinc Panorm’ from Marseille suggest the family’s point of entry into France.

Although some work may have been available for Panormo in the French capital, it was probably not easy to find, as foreigners were ineligible to join any of the more than one hundred Parisian guilds that sought to monopolize production of all goods. Under this arrangement musical instrument makers were obliged to take a six-year apprenticeship before working as a journeyman. Only then, after continued study and payment of not inconsiderable fees, could they be accepted as a master and allowed to operate a business at home or from a separate shop, but not both.

Such was the control exerted by the guilds over the working life of the population that Panormo would have been forced to work in one of the ‘lieux privilégiés’ (places of privilege) to be found in the suburbs of most major cities, nominally outside the jurisdiction of the official guilds. The best known of these ‘lieux privilégiés’ in Paris was the Faubourg St Antoine, home to hundreds of carpenters and cabinet makers, often from abroad, and where Nicolas Pierre Tourte began his career as a carpenter before declaring himself a luthier in 1742.

An internal brand from the c. 1790 viola

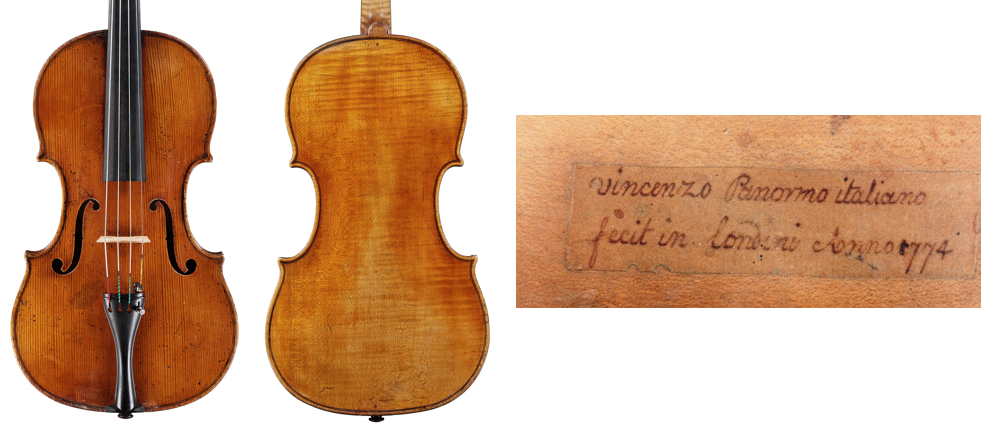

Nevertheless, working in these areas was not without its difficulties as the ‘chambrellans’, or false workers, were considered by many guilds to undermine their monopoly and were often subject to searches by the authorities. In 1785 the guild that Panormo would later register with repeatedly confiscated the materials of the piano maker Sébastien Erard because he was perceived as a threat to its members who made harpsichords. Perhaps under such circumstances Panormo experienced hardship and this might have been why he eventually moved his young family to London in 1772. Whether Panormo continued to make woodwinds in London has yet to be determined but he was certainly producing violin family instruments there, judging by a fine viola bearing a manuscript label dated 1774.

Panormo viola dated 1774, which helps to confirm his presence in London after 1772. Photo: Hiroko Umezawa, courtesy J.&A. Beare Ltd

By 1776, according to a reference in George Burney’s ‘Musical Diaries’, Panormo had opened a music shop in Little Newport Street, Soho. Now at the heart of London’s Chinatown, Little Newport Street and its surrounding area were developed towards the end of the 17th century after demolition of the extensive grounds containing Newport House. Newport Market to the north became one of the principal meat markets in London, while the surrounding streets attracted a large number of French Huguenots. It rapidly became a community of small businesses, described in 1720 as ‘ordinarily built and inhabited; being much annoyed with Coaches and Carts into So Ho, and those Parts’; but it was also a ‘Place of good Trade’ with numerous French restaurants and cafes (John Strype, ‘A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster’). Many of Vincenzo’s new neighbours would have been craftsmen, in particular goldsmiths and jewellers, as well as a number of painters. For Panormo, arriving from Paris, it would have been an obvious district in which to settle, particularly as it was distant enough from the City of London to allow trade to continue unhindered by the counterparts of the French guilds, the City of London’s livery companies.

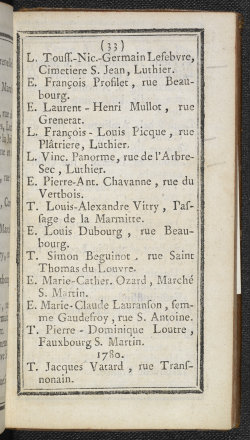

The record showing Panormo’s registration as a luthier in Paris in 1779

Although by the time Vincenzo arrived in London these livery companies were gradually losing their influence, in France the centuries-old structure of labour that may have contributed to his departure was dramatically overturned. In February 1776 the Controller of General Finances in France, Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, issued his Six Edicts, intended as part of an ambitious program of social reform and deregulation of working practices, the longest of them being the abolition of the ancient guild system. This brought about a wave of disorder, Turgot was dismissed by Louis XVI and the guilds were re-established in August the same year. However, this was not just a simple reversion of policy; although in Paris this reorganization proceeded slowly, the power of the guilds was significantly reduced, resulting in far greater accessibility to trades, and with many becoming open to women and outsiders for the first time. Several were also forced to amalgamate with other guilds, including the Company of Musical Instrument Makers, first established in 1599.

This must have been the stimulus for Vincenzo to return to Paris, for on October 5, 1779 he was received as a ‘Maître tabletier et luthier’ in the ‘Classe des nouveaux Maîtres’ of the ‘Communauté des Maître et Marchands Tabletiers, Luthiers, Éventaillists de la ville, fauxbourgs & banlieue de Paris’, his address given as rue de l’Arbre-Sec. Panormo was to remain in Paris until the upheaval of the French Revolution forced him to flee the city. A rare manuscript label inside a cello dated 1791 that has been authenticated as by the same hand as the 1774 viola label confirms his return to London.

An exhibition of Panormo’s instruments, including a catalog containing more information about the recent archival research, is being organized in collaboration with Tarisio in October 2016.

Maker and restorer Andrew Fairfax has researched and written about numerous aspects of violin history, making and restoration. He is co-author of ‘The British Violin’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ books.