Over the course of the 20th century, three important female violinists made their careers with the 1709 ‘Scotta’ Stradivari: Frida Scotta, Mathilde Kaulbach and Barbara Kempner. In the 1990s the violin was gifted to the Marlboro School of Music and last year, Tarisio sold the ‘Scotta’ Stradivari to an anonymous patron for the long-term use of the Finnish violinist Pekka Kuusisto.

Frida Scotta (1871-1948)

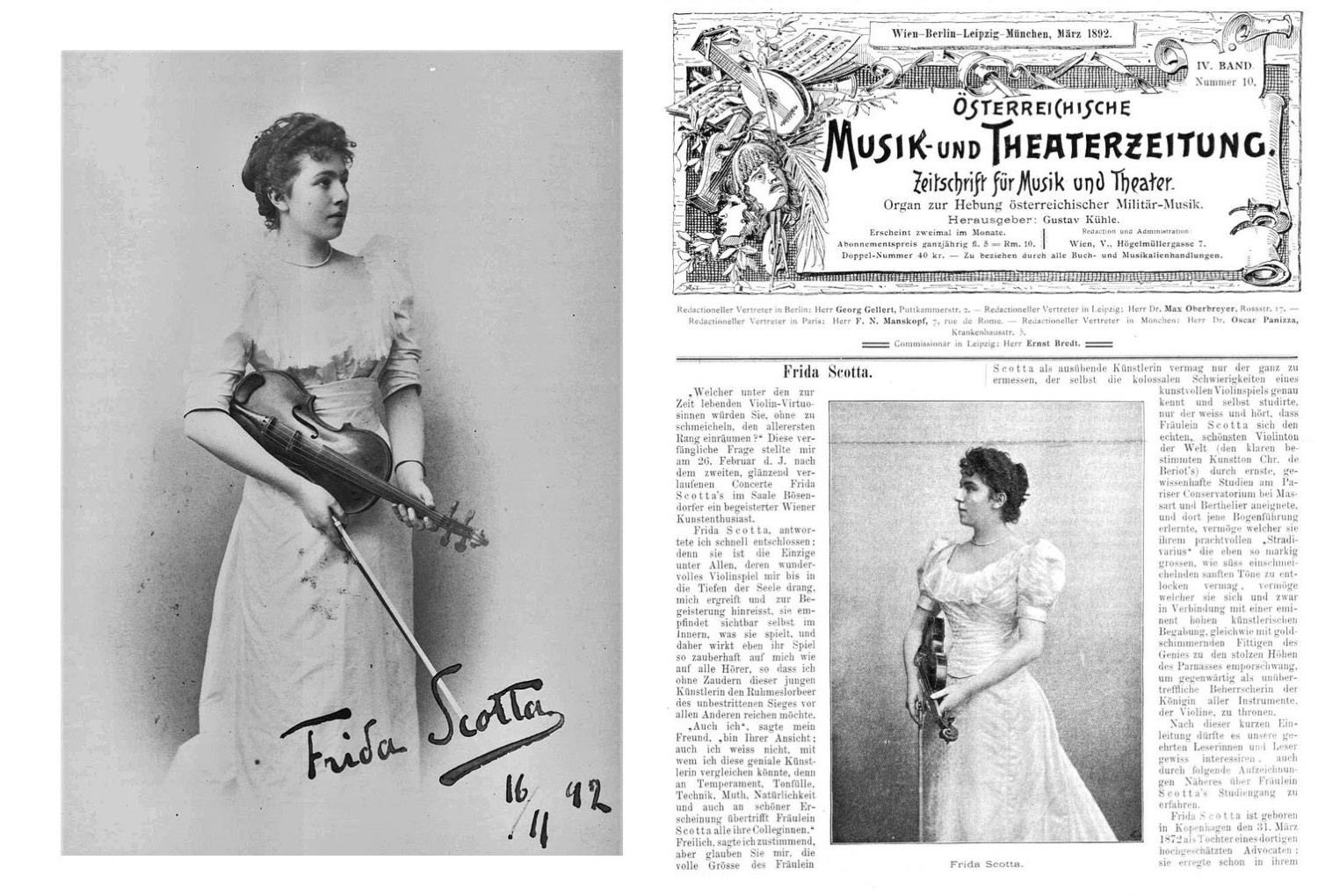

In the late 19th century, the young Danish violinist Frida Schytte (1871-1948) had begun to attract international attention as a rising star. She had taken the stage name Frida Scotta, perhaps because it was easier for foreign audiences to pronounce. She won the Premier Prix at the Paris Conservatory in 1890 after studying with Henri Berthelier and Lambert Massart, who also taught Fritz Kreisler, Eugène Ysaÿe and Henryk Wieniawski.[1] She gave concerts throughout Denmark, Sweden, Germany, France and England and was awarded the Danish “Order of Merit” by the King and Queen of Denmark.[2]

Frida Scotta, painted by her husband Friedrich August von Kaulbach in 1901. (Karl Ernst Osthaus Museum, Hagen)

She played a 1709 Stradivari and told Arthur Hill that it had been loaned to her by a Danish family.[3] At some point, she inherited or purchased this instrument, and it became known as the ‘Scotta’ Stradivari; she kept it for the rest of her life.

Frida Scotta in Österreichische Musik-und Theaterzeitung, March 1892.

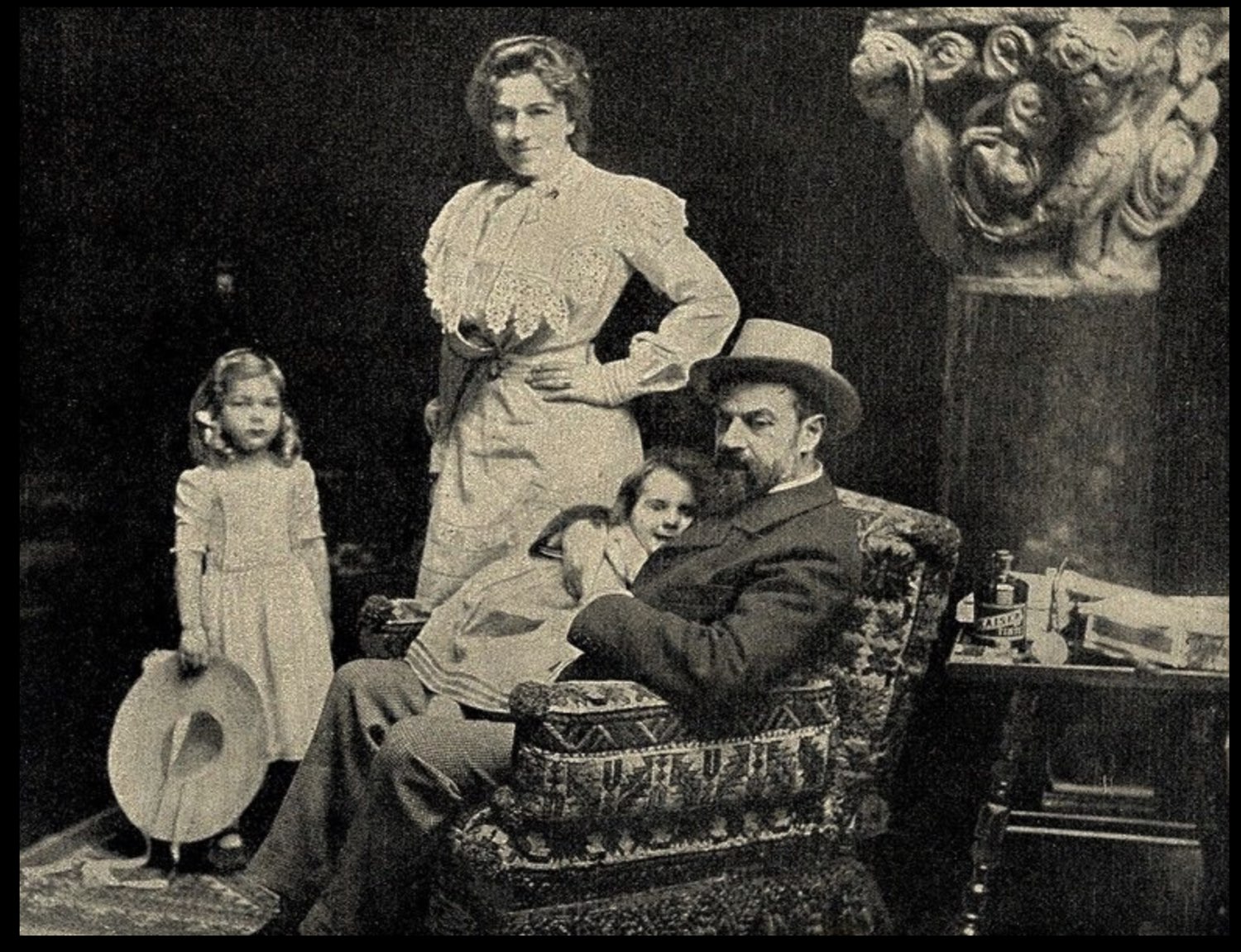

In 1897 Scotta married the German portrait painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920) and moved to live with him in Munich. The couple had three daughters, Doris (1898-1950), Hedda (1900-1992) and Mathilde (1904-1986). All three children learned music and they performed with their mother in a string quartet. Frida and Mathilde on the violin, Doris on viola and Hedda on cello. After the death of her husband in 1920, Frida retired from public life to their country house in Ohlstadt where she died on April 29, 1948. Frida bequeathed her beloved Stradivari to her daughter Mathilde.

Frida Scotta with her husband Friedrich August von Kaulback and their eldest daughters Doris and Hedda in 1902.

Mathilde Kaulbach (1904-1986)

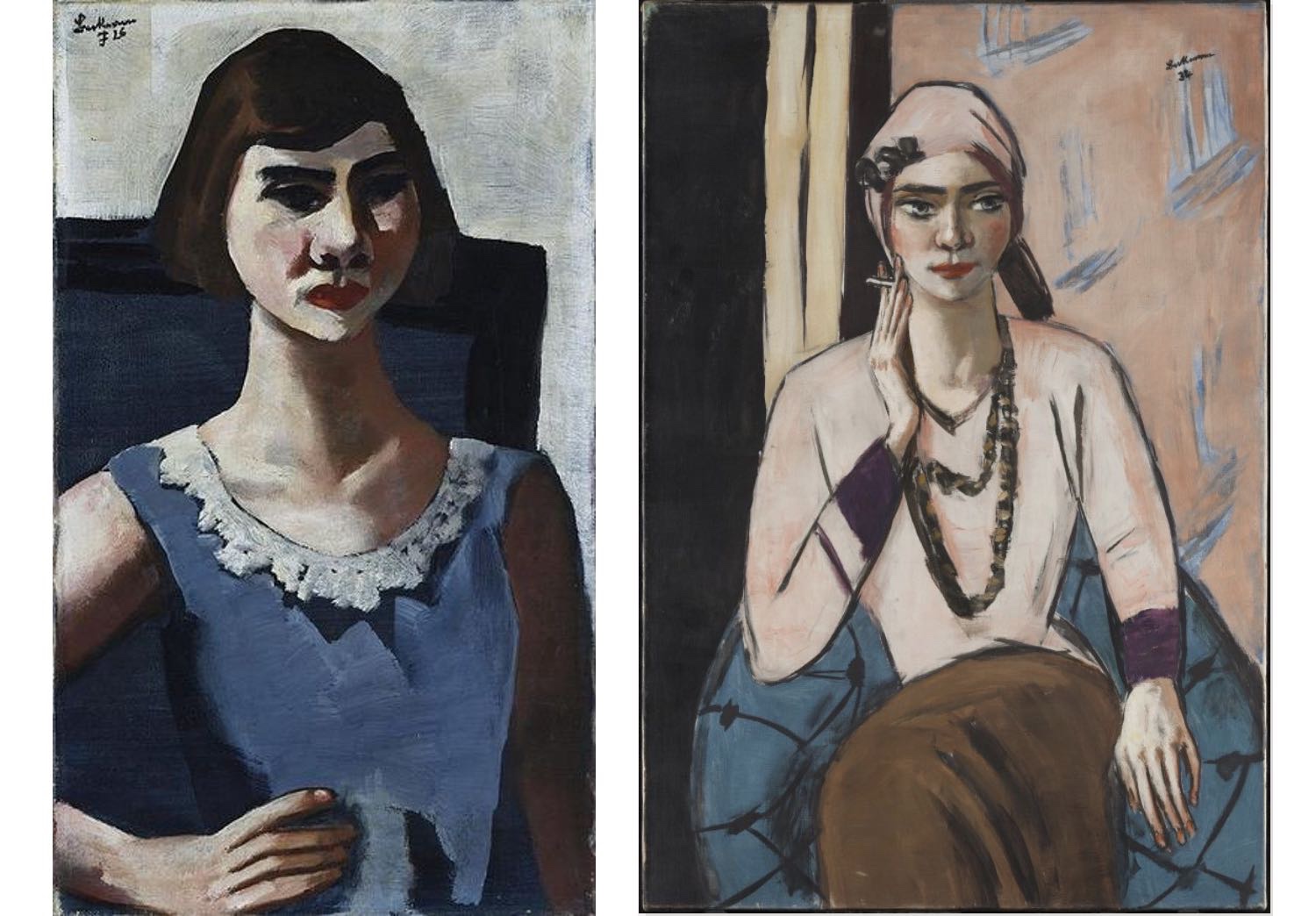

Scotta’s third child, Mathilde Kaulbach, who went by the nickname “Quappi,” studied voice and violin in Munich and Vienna. In 1925, she was offered a position at the Dresden State Opera which she declined. Like her mother, Kaulbach too had met and fallen in love with a painter, Max Beckmann (1884-1950), and changed the course of her career to accommodate his. The two were married in 1925 and moved to Frankfurt where Beckmann was offered a teaching position at the Kunstgewerbeschule of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut.

Mathilde and Max Beckmann in Baden-Baden in 1928.

Two portraits of Mathilde Beckmann by her husband Max (left) Quappi in Blue, 1926 (Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich) and Quappi in Pink Jumper, 1932-1934 (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid)

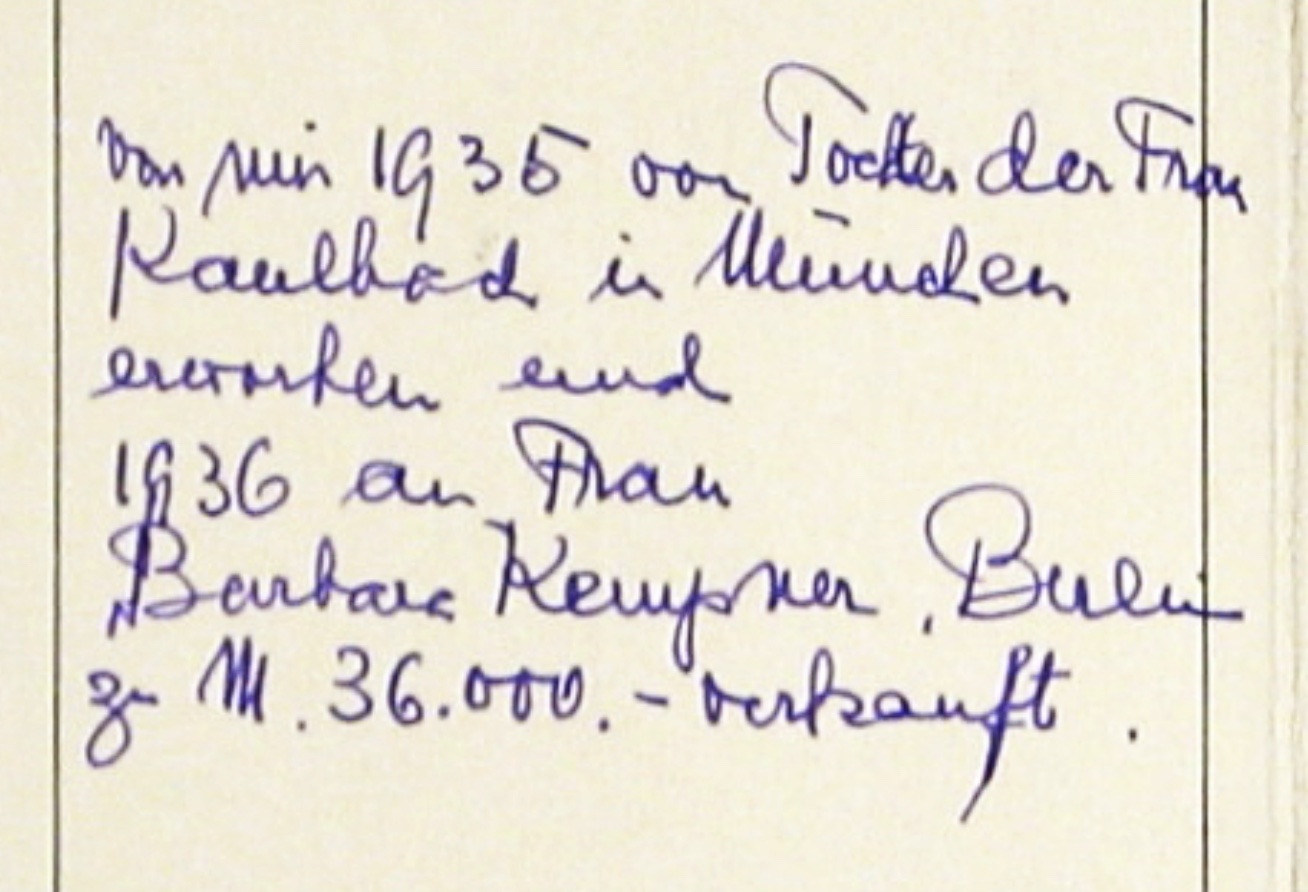

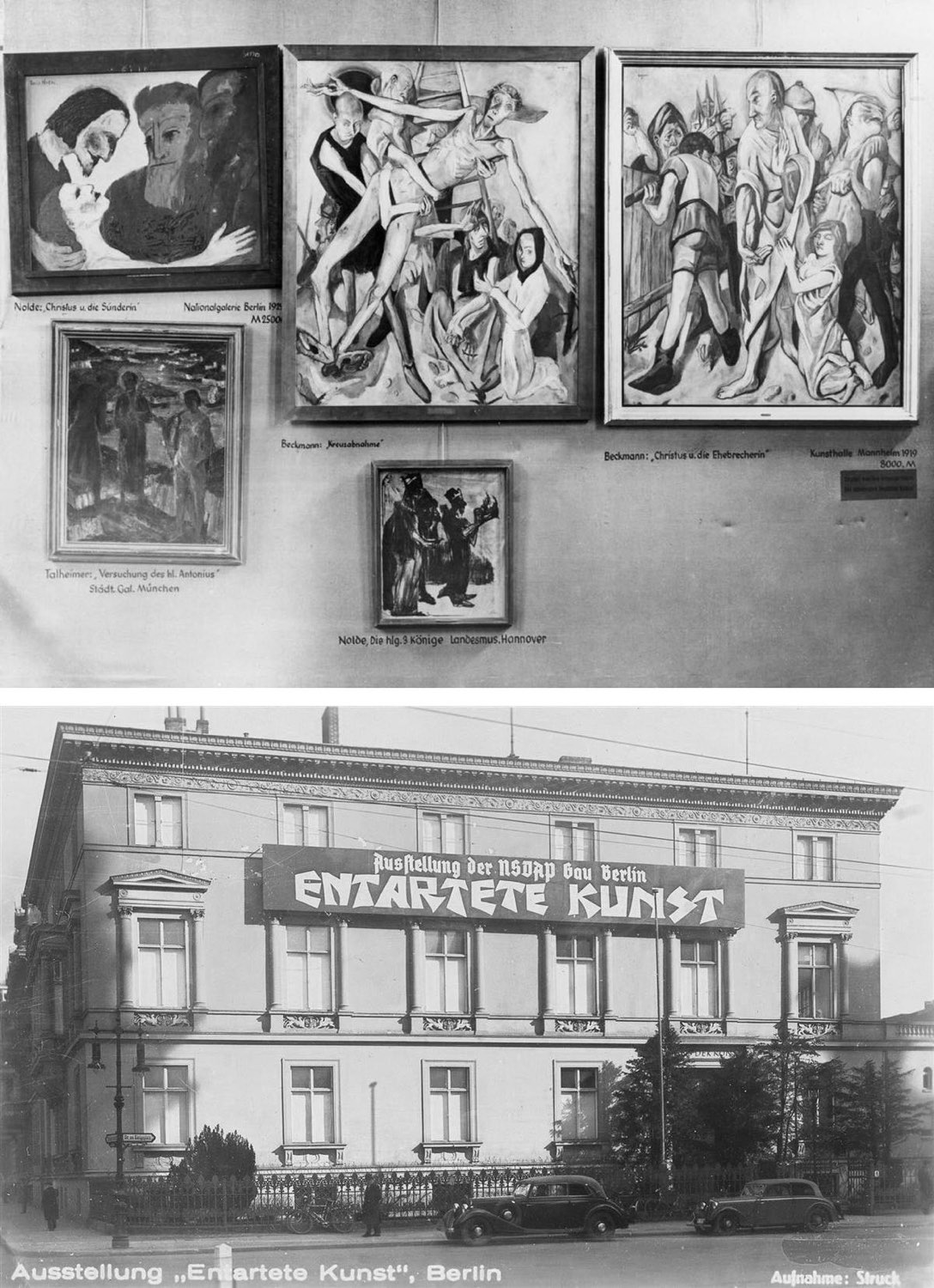

As the political climate in Germany began to change in the mid-1930s, so too did Beckman’s reputation. With the Nazis in power, modern art was denounced and censored. Beckmann lost his teaching position in 1933, and much of his work was removed from the museums and galleries where they had previously been displayed. In 1933 Mathilde and Max moved to Berlin and in 1935, perhaps foreseeing future uncertainties, Mathilde sold the Stradivari to Emil Herrmann, then the leading dealer in Berlin. Two years later after Hitler’s denouncement of Entartete Kunst (degenerate art), the couple was forced to leave for Amsterdam. Later, they immigrated to America after the end of the Second World War.[4]

From the Emil Herrmann archive at the Smithsonian institution, the inventory record for the ‘Scotta’ Stradivari noting that Herrmann bought the violin from the “daughter of Frau Kaulbach in Munich” in 1935 and sold it the year later to Barbara Kempner for 36,000 Marks.

Beckmann accepted academic positions first in St. Louis and then later New York City. Quappi translated his lectures into English and acted as an interpreter in his classes. Beckmann never returned to Germany and died in 1950. Mathilde remained in New York and managed her husband’s estate until her death in 1986.[5]

Max Beckmann’s work at the “Entartete Kunst” (the “Degenerate Art Show”) in 1937.

Barbara Kempner (1903-1997)

Barbara Hildebrand was born in Basel in 1903 and studied under Adolf Busch in Berlin during the 1920s.[6] She married Friedrich Kempner, an Oxford educated lawyer working for his family’s law practice in Berlin. The Kempner family was wealthy and lived in the affluent Westend of Berlin. Barbara bought the ‘Scotta’ Stradivari in 1936 from Emil Herrmann. The couple had no children.[7]

Friedrich Kempner’s older brother Paul was married to Margarethe Mendelssohn, an heir to the Mendelssohn banking fortune. Paul became an important executive at Mendelssohn & Co. With help from the Mendelssohn family’s connections, Friedrich, Paul, and their wives fled Germany in 1938. By this point, the Nazi regime had implemented strict laws regarding the exportation of assets by Jewish families, including their musical instruments. Owing to their family connections, however, the Mendelssohn’s emigration was easier than that of other Jewish families.[8] Friedich was listed as “Financial Expert” on immigration papers[9] and the two couples left for England in 1938, before traveling to the United States one year later. The 1709 Stradivari left Germany with Barbara.

Barbara and Friedrich settled in Manhattan.[10] At the age of 50, Freidrich entered New York University School of Law and received his second law degree in 1941; he would go on to become a partner at Cahill Gordon & Reindel.[11] Barbara reconnected with the violinist Adolf Busch who had also immigrated to the United States in 1939 after leaving Berlin for Switzerland in the late 1920s.

The Busch clan was central to musical culture in the United States, particularly, the development of chamber music. Between 1950 and 1951, Adolf Busch founded the Marlboro Music School with his brother Hermann, his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, and Marcel, Blanche and Louis Moise. Barbara Kempner performed in the Busch Ensemble and played a vital part in the establishment of Marlboro. She donated the ‘Scotta’ Stradivari to Marlboro in 1991. In 1997, at the age of 95, Barbara passed away.[12]

Marlboro’s founders: Marcel Moyse, Louis Moyse, Rudolf Serkin, Blanche Moyse, Adolf Busch, Hermann Busch (with cellist Nathan Chaikin second from left) (https://www.marlboromusic.org/about/history/)

For the thirty years that Marlboro owned the ‘Scotta’ it was loaned to many great players whose careers the school molded. Marlboro appointed Tarisio to find a buyer for the violin and in 2021 Tarisio sold the ‘Scotta’ to an anonymous patron for the long term use of Finnish soloist Pekka Kuusisto. In a recent profile in The Strad magazine, Kuusisto shared the following remarks about his experience playing this extraordinary violin:

“I haven’t met a fine instrument with this kind of magic before…It has power and it’s glorious and it sort of soars, but when you play quietly on it, suddenly all these colours, all these vowels and consonants want to be used…Every day there is something new.”

Pekka Kuusisto © Felix Broede

Notes:

1. She was also a student of Berthelier, see The Strad magazine, January 1893.

2. Le Monde artiste : théâtre, musique, beaux-arts, littérature, Paris, 12 November 1893, p. 749.

3. The Business Records of W. E. Hill & Sons, 1893 (unpublished).

4. Rihoko Ueno, “A Finding Aid to the Max Beckmann papers, 1917-1954, in the Archives of American Art,” Smithsonian Museum of Art, accessed on 1 November 2022, https://sirismm.si.edu/EADpdfs/AAA.beckmax.pdf.

5. Matilde left an estate consisting of paintings worth over $9m in 1987. Grace Glueck, “The Court to oversee Max Beckmann’s estate”, The New York Times, January 31 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/01/31/arts/court-to-oversee-max-beckmann-s-estate.html.

6. Stephen Lehmann and Marion Faber, Rudolf Serkin: A Life, Volume 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 40.

7. Hartmut Röhn, Jüdische Schicksale: Ein Gedenkbuch für die Stadt Werder (Havel) und ihre Ortsteile (Berlin: Lukas Verlag, 2016), 71.

8. Fritz Kempner, Looking Back (Self-published, 2006), http://www.penncharter60.org/faculty/Looking%20Back.pdf.

9. New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1957, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7488/images/NYT715_6395-0424.

10. Fritz Kempner, Looking Back, 2006.

11. “Frederick C. Kempner,” The New York Times, 11 July 1981, https://www.nytimes.com/1981/07/11/obituaries/frederick-c-kempner.html.

12. “Paid notice: Deaths Kempner, Barbara,” The New York Times, 20 March 1997, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/03/21/classified/paid-notice-deaths-kempner-barbara.html.