The Mantegazza family worked in Milan, Italy, in the 18th and 19th centuries and were among the first violin makers to offer a range of services comparable to those of a modern violin shop. In addition to making new instruments, they also repaired, modernized and set up older instruments, bought and sold, and provided expertise.

The first and most prolific maker of the family, Pietro Giovanni Mantegazza (c. 1730–1803), was a student of Carlo Ferdinando Landolfi. His own instruments date from around 1760 and it appears that he also worked with his brother Domenico Mantegazza (active c. 1776–1783) – although there is no record of Domenico in the Milan city archives, early correspondence from Count Cozio di Salabue is addressed to ‘i fratelli Pietro and Domenico Mantegazza’. After the death of Pietro the business passed to his sons, Francesco (1762–1824) and Carlo (1772–1814), who were also known as ‘Fratelli Mantegazza’. A third violin making son named Antonio (1766–1790) unfortunately died prematurely, while according to Count Cozio there was another son named Paolo, but nothing more is known of him. With a multi-faceted enterprise that likely left little time to make new instruments, the individual labeled work of the sons is rare; however, later examples of Mantegazza instruments bearing the label of Pietro were probably made with the assistance of the sons.

Pietro Giovanni’s label was probably also used for instruments made by his sons

The Mantegazza family’s place in violin making history is partly a reflection of the period in which they worked. The late-18th century was an interesting juncture between the end of the classical Italian violin making period and the start of the modern era typified by 19th-century copyists such as J.B. Vuillaume and Giuseppe Rocca. Beginning in the 16th century with Andrea Amati and peaking in the early- to mid-18th century with the works of Antonio Stradivari and Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, the demand for violin-family instruments fueled the work of some of the greatest craftsman that have ever lived. In Cremona alone in the early 1690s there were no fewer than five violin shops, including Antonio Stradivari, Girolamo Amati II, Andrea Guarneri, Vincenzo Rugeri and, outside the walls of the city, Francesco Rugeri. While there are occasional examples of repair work, these shops primarily specialized in making new instruments. It was only in the late-18th century that a growing interest in older instruments turned repair work into a full-time profession. This also created an ancillary need for expertise and authentication as well as a secondary market for buying and selling.

Cozio referred to Carlo Mantegazza as ‘perhaps the most celebrated instrument repairer there ever was’

At the forefront of this was Count Cozio di Salabue. A tireless enthusiast, chronicler and collector, he owned a number of important Italian instruments, corresponded with many of the leading Italian violin makers of the day and was a patron of G.B. Guadagnini. In the mid-1770s the Mantegazza family became a trusted resource for Cozio, whose records show that he had ongoing business with both generations of the family. This included repair work and especially modernizing instruments (fitting new fingerboards, necks and bridges) that had previously been set up to Baroque performance standards. Cozio wrote in his notes: ‘Now he (Carlo Mantegazza) has so much work modernizing old instruments that he and his brother live more from that than from making new ones.’ Cozio also referred to Carlo as ‘perhaps the most celebrated instrument repairer there ever was’ and entrusted him with varnishing some unfinished instruments in the white that had been made by Guadagnini.

Cozio sought advice from the Mantegazzas on other violin-related matters as well, including information about instruments and their makers, and assistance with buying and selling. In a letter sent through Cozio’s agent G.M. Anselmi, he requested that the Mantegazzas issue a certificate of authenticity with the following text:

We brothers Mantegazza, instruments makers in Milan for many years certify to have sold to Mr. Giovanni Michele Anselmi of Briatta, of the city of Turin, many instruments like new and intact containing labels of Antonio Stradivari of Cremona, which he had made over several years. They are truly genuinely by this maker. We know that they have been bought from Paolo Stradivari, son of Antonio, and merchant in Cremona, who had inherited them from his late father, the maker himself.

In witness of above, where we have certified and signed.

Brothers Mantegazza, Milan, April 17, 1776

As the leading violin shop in Milan, the Mantegazzas attracted musicians among their clientele. These included Alessandro Rolla, the well-known violinist and concertmaster of Milan’s La Scala orchestra. Cozio’s notes record a meeting between Rolla and Francesco Mantegazza to view the ‘Archinto’ Stradivari viola: ‘Francesco Mantegazza told me that he saw the instrument at [the residence of] Mr. Rolla Alessandro as soon as it reached Milan. He listened to it; its voice was good, but not of a great quality…’

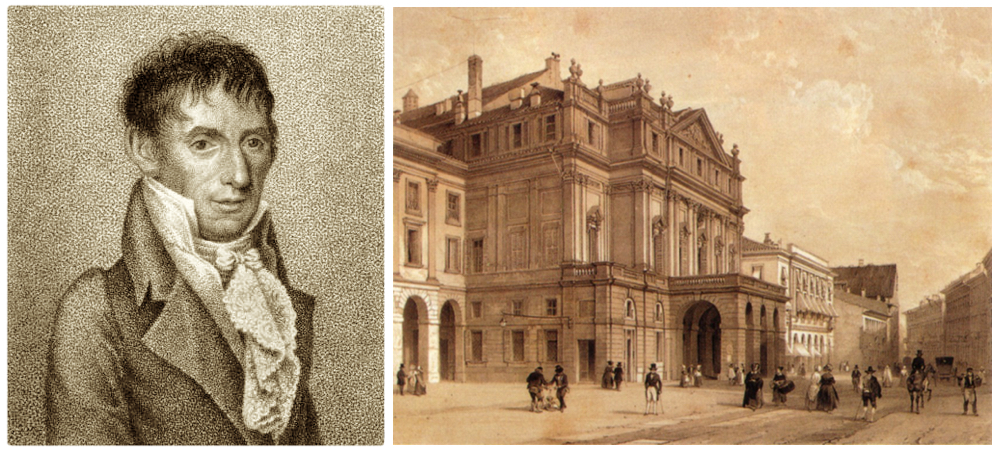

The Mantegazza shop’s many clients included the violinist Alessandro Rolla (left, engraving by Luigi Rados), who was concertmaster of Milan’s La Scala orchestra (right, La Scala in the 18th century)

While Rolla was a well-respected violinist in his own right, he is perhaps better known as one of the teachers of Nicolò Paganini. In 1813 Paganini performed on the stage of La Scala to great acclaim and would go on to perform in all the major musical capitals of Europe. In addition to his performing career, Paganini collected musical instruments, including a quartet of Stradivaris. In a letter dated 1823 he wrote to his friend Luigi Germi stating: ‘Your Guarneri had a superb reception in Milan, and Mantegazza is taking extraordinary pains with it…’

‘Your Guarneri had a superb reception in Milan, and Mantegazza is taking extraordinary pains with it’ – Nicolò Paganini

After approximately 60 years in business the Mantegazza dynasty came to an end in 1824 with the death of Francesco Mantegazza. Giacomo Rivolta was then the most significant maker in Milan and, like the Mantegazzas, was in close contact with Count Cozio. As the demand for antique instruments continued into the 19th century and beyond, so did the model of the violin maker as dealer, repairer and expert, which is perhaps best epitomized by the famous ateliers of J.B. Vuillaume in Paris and W.E. Hill and Sons in London. While the vast scope and set-up of these later shops dwarfs the more humble artisan-style business of the Mantegazza family, the roots of their various activities can be traced back to the transitional time of the late-18th century.

Instruments

Most of the extant examples with original labels bear the name of Pietro Giovanni Mantegazza and, as one might expect, the workmanship displays a broad range of experience with the work of earlier makers. There are instruments based on models by Guadagnini and Amati as well as examples that show the influence of Landolfi and Stradivari. However, rather than making precise bench copies, the Mantegazzas appear to have been highly informed luthiers who derived inspiration from various sources. In this respect, a comparison can be drawn to G.B. Guadagnini who, like the Mantegazzas, did repair work for Cozio and therefore had first-hand experience with his collection. Not surprisingly, Guadagnini’s production in Turin after he met Cozio is influenced by Stradivari. While these instruments are not attempts to make an exact copy, they do incorporate Stradivari features of arching and workmanship into an existing concept. Even though the Mantegazza instruments are perhaps bland next to the more characterful work of Guadagnini and the varnish is not of the same lustre (especially on some of the examples made after 1790) they are similarly well informed and sophisticated in approach, successfully combining a knowledge of older instruments with evolving playing styles. From their early Landolfi-inspired model, which has a squarer arch and outline and stiffer workmanship, there is a progression to a more polished approach with flowing outlines and smooth, highly finished surfaces.

Pietro Giovanni Mantegazza, cello c. 1770

This rare example of a cello from the Mantegazza workshop shows the early style of Pietro Giovanni with a squarish-shaped outline, stiff-looking f-holes and longish C-bouts. The deeply carved scroll with the concentric turns of the volute is a characteristic feature throughout the working life of the shop.

Pietro Giovanni Mantegazza, viola c. 1760

Similar to the c. 1770 cello, this is another characteristic example of the Landolfi-type of Mantegazza. It is likely the individual work of Pietro or possibly was made with the assistance of his brother Domenico.

Pietro Giovanni Mantegazza, violin c. 1770

Contemporaneous with Pietro Giovanni, G.B. Guadagnini worked in Milan from around 1749–1758. The rounded outline of this example and especially the oval-shaped lower lobes of the f-holes are a clear homage to the work of Guadagnini.

Pietro Giovanni Mantegazza, violin c. 1780

A fine and characteristic example of Pietro’s mature style with the possible assistance of his sons. Compared with the early Landolfi-inspired examples, the outline and arching are more rounded and less square, probably due to the influence of Guadagnini instruments made in Milan. Typical features include the shape and placement of the f-holes and their small upper and lower lobes; the Milanese-style pinning on the back with a top and bottom pin placed inside the purfling and slightly off-center; the medium-width purfling with mitres pointing mostly toward the middle of the corners and framed by a nicely beaded edge; and the choice of wood with an attractive flamed maple back and a spruce top with fine, prominent grain lines.

Pietro Giovanni Mantegazza, viola 1793

Based on an Amati model, the workmanship of this viola is precise, with a finely executed edge and beautifully cut f-holes that have slender stems and small lobes. Although some of the spontaneity of the earlier work has been lost and the varnish has a slightly dryer, less luminous appearance, there is an admirable level of technical accuracy. While it was likely made in collaboration with the sons, the instrument bears the label of Pietro, as he was still the head of the workshop.

The Mantegazzas made a number of highly successful violas of an ideal size for modern use, with most examples having a back length around 410 mm (there is also a larger type measuring around 430 mm). The 1793 viola in the collection of the National Music Museum in South Dakota (not illustrated here) is of particular interest given its exceptionally pure state of preservation. Remarkably the original neck and fingerboard have been left undisturbed, displaying a ‘transitional’ type of set-up that is somewhere between the traditional Baroque style and what is considered modern by today’s standards.

Francesco Mantegazza, viola 1788

Displaying many of the typical characteristics of instruments from the Mantegazza workshop, this viola (part of the Chi Mei Culture Foundation collection in Taiwan) is a rare example of the sons’ labeled work. A similar example bearing the original label of Antonio Mantegazza dated 1789 is also in the Chi Mei collection.

With thanks to Carlo Chiesa.

Julian Hersh is a cellist, expert and co-founder of Darnton & Hersh Fine Violins in Chicago.

The quotes from Count Cozio’s notes are taken from Memoirs of a Violin Collector by Brandon Frazier.