The chance to own a Stradivari viola doesn’t come around often. Surely, this was what Jean Baptiste Vuillaume was thinking when he discovered this viola in the mid-19th century. He would have instantly recognized its commercial importance and historical rarity and known that his well-heeled customers would jump at the opportunity to own a Stradivari viola. The only problem was, it wasn’t exactly a viola just yet…

• • •

Introduction

The ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ Stradivari began its life as a viola d’amore, a six-stringed viol played under the chin with a second set of strings that vibrate ‘sympathetically’ with the overtones of the main strings. In the 18th century, viols were on the decline, having lost ground to the more popular violin family instruments. Violins (and violas and cellos) were predictably tuned in fifths unlike the scordatura of the viols that varied by repertoire; violins were louder and carried melodies more clearly; and, most significantly, violins had arched tops and backs that made them more durable than viols whose flat backs tended to crack and warp. Accordingly, players and composers favored the violin, viola and cello, and the viol family fell out of fashion. This was already the case during Stradivari’s life, but a hundred years later, when Vuillaume came into the possession of the ‘Kux’, a viola d’amore was significantly less in demand – and less valuable – than a viola.

But the ‘Kux’ wasn’t a typical viola d’amore, in fact it was much more like a viola than a d’amore: it had viola-shaped corners, sound holes and edges and was even created on the same form that Stradivari used to make his other contralto violas. Vuillaume quickly realized that it wouldn’t take much to convert this pristine but outmoded d’amore into a highly desirable viola, one that would have all the sonority and power of a soloist instrument.

the ‘Kux’ wasn’t a typical viola d’amore, in fact it was much more like a viola than a d’amore: it had viola-shaped corners, sound holes and edges and was even created on the same form that Stradivari used to make his other contralto violas.

The top and ribs of the ‘Kux’ are the work of Stradivari dating to around 1720; the back is a replacement made by Vuillaume in circa 1850 and the head was made by Nicolo Amati in the early 17th century. The ensemble was joined together by Vuillaume around 1850. The ribs have been reduced in height to remove the ‘fold’ of the d’amore’s back, and likewise, the top has been modified slightly to remove the ‘shoulders’ on either side of the neck. The instrument’s original flat back has been lost. The presumed original twelve string head, an ingenious design with two parallel courses of strings, was gifted to the instrument museum of the Conservatoire de Paris by Vuillaume in 1873 and now forms part of the collection of the Musée de la Musique.[1]

Its condition is unprecedented: a small veneer reinforces the sound-post area of the front; the edges are undoubled; the corners are crisp and pristine. The varnish on the front and ribs is heavily pigmented and luminous; its surface is unpolished and nearly without wear. As a specimen of Stradivari varnish the front of the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ rivals the ‘Lady Blunt’ in purity and preservation.

The viola is sold with certificates from Tarisio and from Rembert Wurlitzer. A dendrochronology exam dated the latest rings of the treble and bass sides of the top to 1683 and 1682 respectively.

• • •

The History of the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’

We don’t know how Vuillaume acquired the ‘Kux’—or where it spent the first 130 years of its life—but I have found several tantalizing clues in letters preserved in Count Cozio’s Carteggio that could explain its early history.

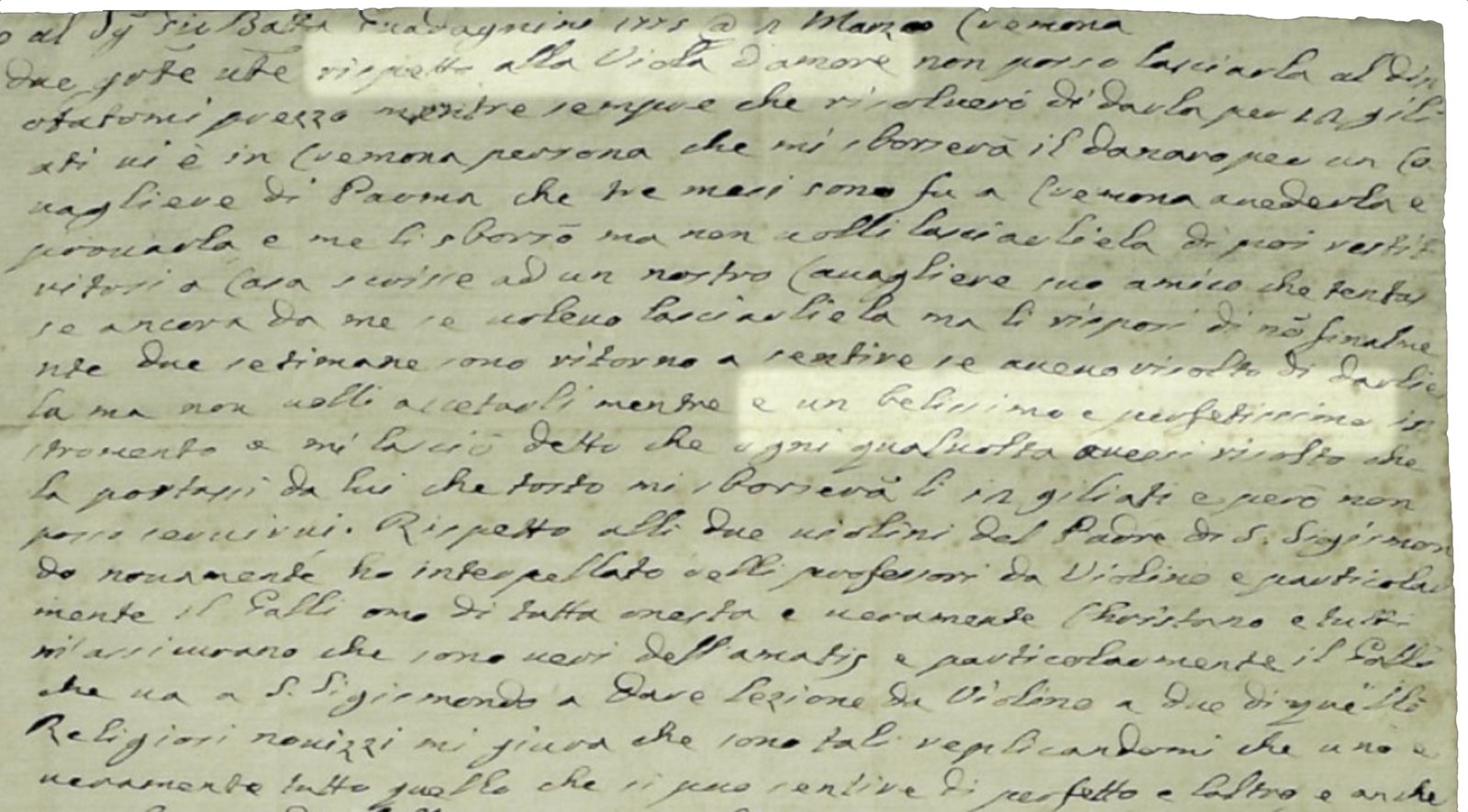

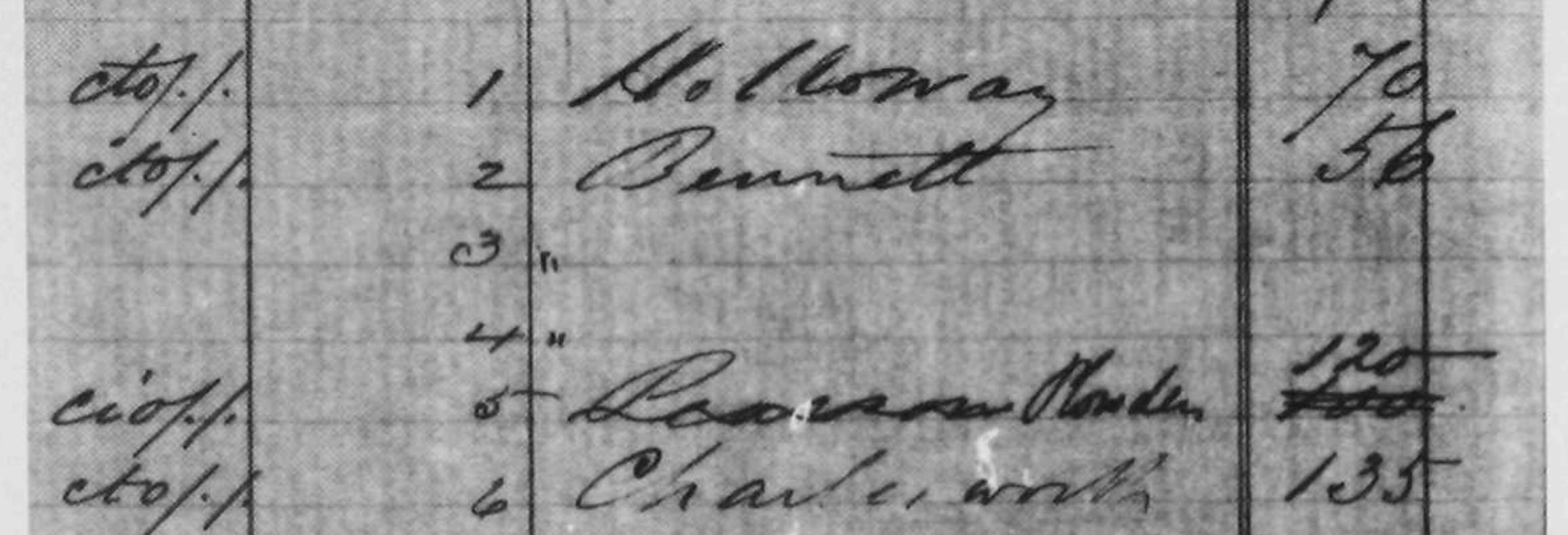

Paolo Stradivari wrote to Giovanni Battista Guadagnini in March 1775 about the “beautiful and pristine” viola d’amore made by his father (highlights mine).

In March of 1775, Cozio contacted Stradivari’s youngest son Paolo through the violin maker Giovanni Battista Guadagnini to negotiate the acquisition of a Stradivari viola d’amore.[2] Paolo replied that he didn’t want to sell the “beautiful and pristine” instrument and had, in fact, already refused an offer of twelve giliati from a gentleman in Parma.[3] Twenty-six years later, Cozio wrote to Paolo’s son Antonio, trying again to purchase the “two perfect condition violas d’amore made by your grandfather”[4] for thirteen zecchini each.[5] At the end of the letter, Cozio added, “P. S. I neglected to mention that I want that the soundholes of these two violas are in the shape of those of normal four-string violas as I intend to have [the instruments] reduced, otherwise it doesn’t make sense to buy them at this price.”[6] It’s thrilling to know that two Stradivari violas d’amore were still “pristine” in 1801. It’s also very revealing that Cozio already saw the value in converting them into traditional violas.[7]

In the postscript to his letter to Antonio II Stradivari, Cozio confirms that he wants the soundholes of the two d’amores to be “in the shape of those of normal four-string violas”, writing “I intend to have [the instruments] reduced, otherwise it doesn’t make sense to buy them at this price.”

We don’t know for sure who owned the ‘Kux’ between Stradivari and Vuillaume. In fact, we can’t even be certain that the ‘Kux’ was one of the two instruments referenced in Cozio’s letters. That said, given the rarity of Stradivari’s d’amores – especially those with corners and traditional sound-holes – it seems very likely. If it wasn’t Cozio who bought the ‘Kux’ from Antonio II Stradivari, then it could have been Luigi Tarisio or even Count Castelbarco himself.

In any event, by the mid-19th century, the ‘Kux’ had landed on Vuillaume’s workbench and was destined for a makeover. After the transformation was completed, the viola ended up with one of Vuillaume’s best customers, Don Cesare Pompeo Castelbarco. Descended from a line of Milanese nobility, Castelbarco was a devoted violinist and composer who was integral to Northern Italy’s musical society during his lifetime. He had a large collection of musical instruments including at least seven Stradivari.[9] Early Stradivari biographer, François Joseph Fetis noted that Castelbarco had assembled two Stradivari quartets.[10] The existence of a second ex-Castelbarco Stradivari viola, however, is not currently known.

by the mid-19th century, the ‘Kux’ had landed on Vuillaume’s workbench and was destined for a makeover.

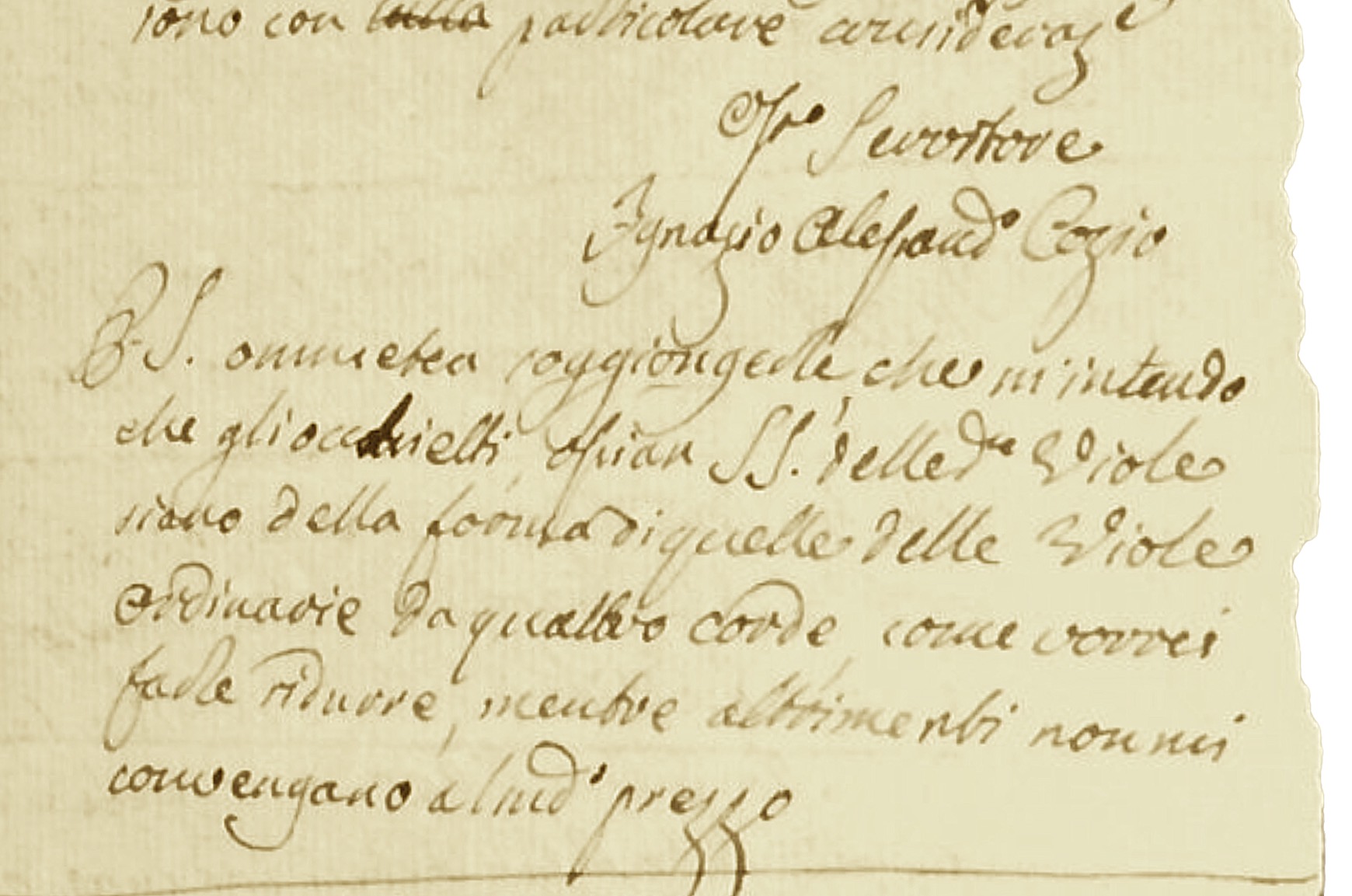

Castelbarco died in 1860. Two years later the London auctioneers Puttick & Simpson sold his collection of musical instruments in what was billed as the “Superb Collection of Cremona Instruments of the late Count Castelbarco, of Milan.”[11] The sale consisted of 31 lots, of which 18 were important violins, violas and cellos. There were also bows, cases and a rare Stradivari letter.

Puttick & Simpson’s auction gallery in Leicester Square. From The Illustrated London News, 13 August 1859 and the title page to the Castelbarco auction of 1862.

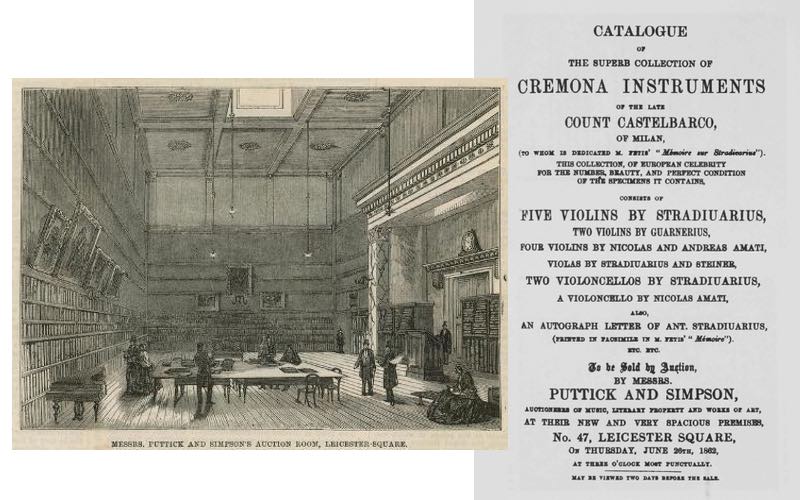

The identity of the ‘Kux’ buyer at the Puttick & Simpson sale remained unknown for over 150 years. However, in the course of researching this instrument, I discovered that the buyer was Charles Hood Chicheley Plowden, an important English collector of musical manuscripts and the owner of several Stradivari and Guarneri instruments including the 1735 ‘Plowden’ ‘del Gesù’.[12] According to the auctioneer’s sale notes preserved in the British Library’s collection, Plowden bought the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ for 120 pounds, approximately double the price of the two Stradivari violins which had been sold immediately before it.[13]

The auctioneer’s notes show a correction to lot 5. Pearson (who bought other lots in the sale) is crossed out and Plowden was recorded as the buyer of Castelbarco’s Stradivari viola for £120.

After Plowden, the viola passed to Charles Wesley Doyle, a violist in the Royal Italian Opera orchestra and a professor at the Guildhall School of Music. Doyle succeeded the renowned English violist Henry Hill, the uncle of the dealers Alfred and Arthur Hill; Doyle sold the viola to the Hill firm in around 1887.[14] The Hills subsequently sold it twice, first to the collector David Johnson, and later to the accomplished amateur violist John Troutbeck, whose day job was coroner for the City of Westminster during investigations into the Jack the Ripper murders in the summer of 1888.

In 1897 Troutbeck consigned the viola to the London dealer George Withers who later sold it to the Stuttgart dealer, Fridolin Hamma.[15] In 1914 the viola came into the possession of Wilhelm Kux, a Viennese banker, amateur musician and patron of music. Kux was an early supporter of Emanuel Feuermann; Pablo Casals attended parties at his house; and Erica Morini, Norbert Brainin and Clara Haskil all passed through his musical salons.[16] He had an important collection of musical instruments and manuscripts and was on the board of directors of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde Wien, the official name of the Musikverein between 1925 and 1938.[17] According to Rembert Wurlitzer, it was Arnold Rosé, the leader of the Vienna Philharmonic for over half a century, who introduced Kux to this Stradivari viola. According to Wurlitzer, Adolf Busch played on the viola and Bronisław Huberman used it for a performance in the large hall of the Musikverein to great acclaim.[18] After the Anschluss on March 13, 1938, Kux fled Vienna for Switzerland, escaping with his musical instruments.

Wilhelm Kux (left) with his parents Charlotte and Markus in c. 1890.

In the early 1950s, Kux entrusted the viola to his nephew, Ernst Glasner, who had immigrated to America and lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.[19] Glasner consigned the viola to Rembert Wurlitzer in 1957, and sold it to the Wurltizer firm a year later. In 1958 it was bought by Benjamin Cooper of Weston, Connecticut.[20] Six years later the viola came back to Wurlitzer and shortly thereafter was bought by the violinist, conductor and entrepreneur David Josefowitz for the Fridart Foundation. From 1998 to 2013 the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ was on loan to the Royal Academy of Music in London where it was in the company of Stradivari’s ‘Archinto’ viola of 1696.

• • •

Recreating Stradivari’s Viola D’Amore

In addition to violins, violas and cellos, Stradivari produced other instruments such as guitars, harps, pochettes, viols and mandolins. Many of these have since been lost or altered but by studying Stradivari’s drawings, models, forms and templates, we can begin to understand the original format and construction of many of these lost or modified instruments.[21]

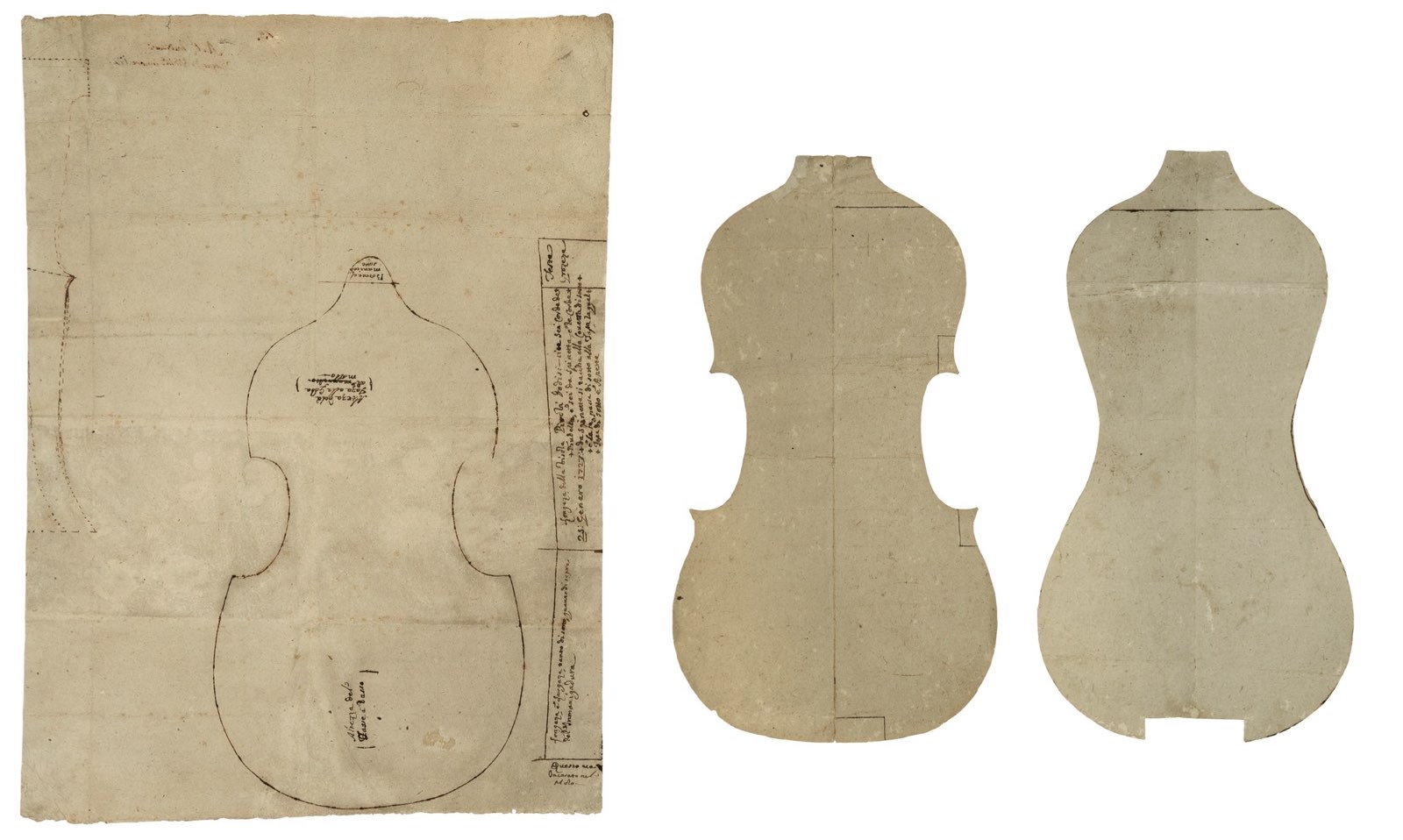

In the Museo del Violino collection in Cremona there are plans and drawings for instruments whose outlines are similar to that of the ‘Kux’ though nothing has its exact dimensions. These include a tracing of a traditional viola d’amore with sloped shoulders and viol-shaped corners (MS344); two paper patterns for a smaller soprano violino d’amore with violin-shaped corners (MS364 and MS365); and several paper patterns for cornerless viols (MS368 and MS369).

At left: a tracing that Stradivari made of a traditional model viola d’amore (MS 344); middle: a paper pattern for a smaller soprano viola d’amore with corners (MS 365); and right: the design for a form for a cornerless soprano viol (MS 368). © Museo del Violino, Cremona.

At first I was disappointed not to find the plans for the ‘Kux’ at the Museo del Violino until I realized that the model and form were right in front of me: Stradivari didn’t create a new pattern to make the ‘Kux’, he used his regular contralto viola form (“C.V.”, MS205), the model upon which he had built violas for the previous thirty years.

Stradivari’s ‘C.V.’ (contralto viola) form (MS205) and paper templates for the contralto bridge (MS873) and soundhole stems (MS866). (not to scale). © Museo del Violino, Cremona.

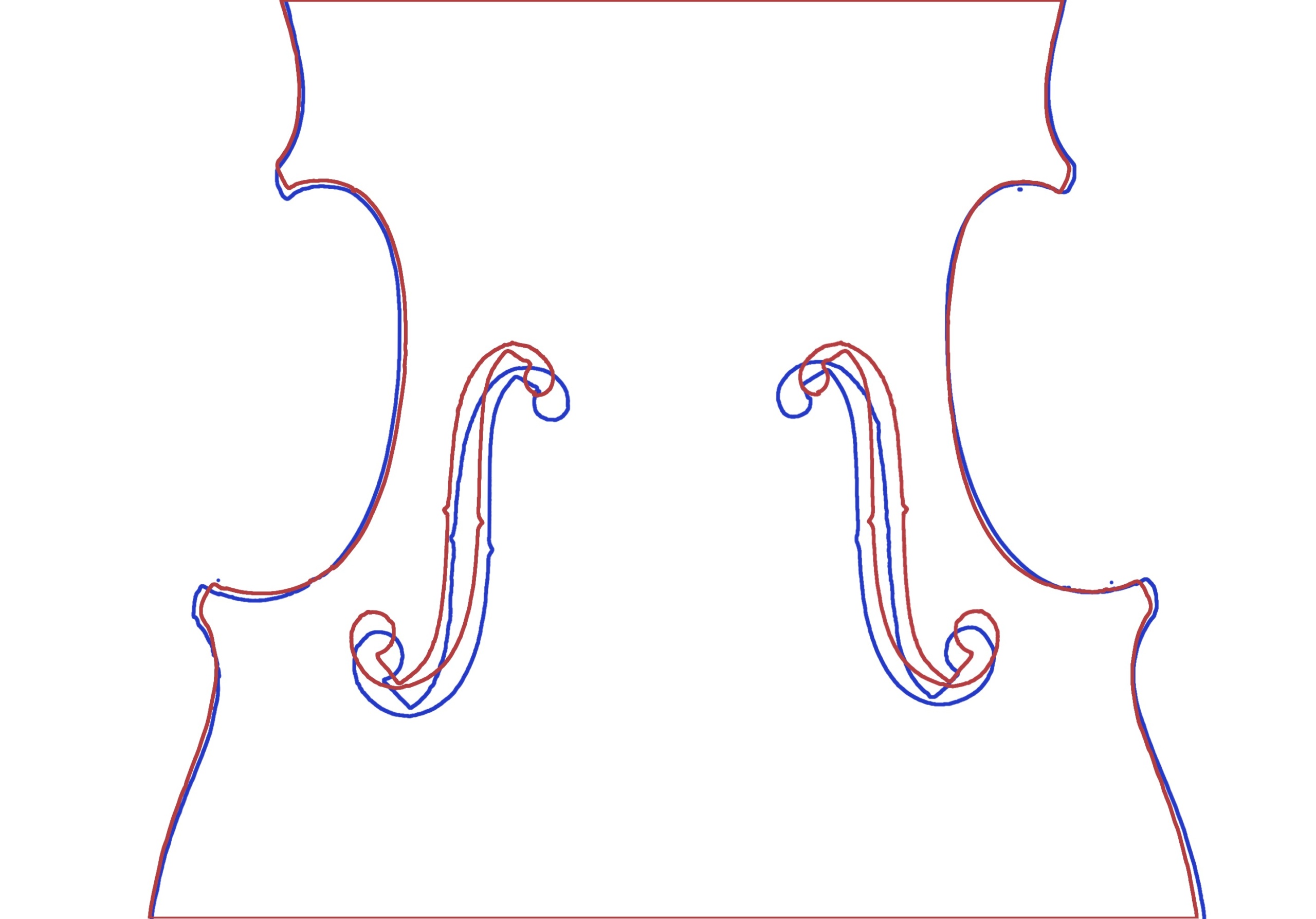

Overlaying a partially transparent image of the ‘Kux’ onto the C.V. form reveals that the position of the corners, the contours of the ribs and the widths of the bouts align perfectly; only the upper edge is slightly reduced where the original viol shoulders were removed. Superimposing the outline of the ‘Kux’ onto that of the 1696 ‘Archinto’ Stradivari, also made on the C.V. form, doubly confirms the match.

Left: the ‘Kux’ overlayed onto Stradivari’s ‘C.V.’ form; right: the outlines of the c. 1720 ‘Kux’ (red) and the 1696 “Archinto” (blue) (taken from photographs).

I suspect that Stradivari used the C.V. pattern because it worked acoustically and was an easy conversion to a hybrid d’amore. The corner blocks and the lower block would have been prepared as normal albeit slightly taller to produce deeper ribs. The upper block would have been made wider and taller to stand proud of the form and to allow the maker to carve the concave shoulders onto which the upper ribs would have been glued. The neck would have been set into the upper block probably by means of a dovetail joint. There are several paper templates in the Museo del Violino collection that illustrate how the neck of a viol should be dove-tailed into the upper block.

Stradivari used the C.V. pattern because it worked acoustically and was an easy conversion to a hybrid d’amore

Stradivari probably used a modified upper block to adapt the C.V. form to make the ‘Kux’. Here, the upper section of the C.V. form (MS205) is overlaid onto an enlargement of Stradivari’s pattern for a soprano d’amore (MS365). A small paper template (MS329) shows how the neck would have been set in a dove-tail joint. (objects not to scale). © Museo del Violino, Cremona.

The other deviation from the C.V. pattern can be seen in the positioning of the sound-holes. A d’amore requires a wider bridge to accommodate six strings which in turn needed a greater distance between the sound-holes. Consequently, the upper sound-holes of the ‘Kux’ are set 54.6 mm apart whereas this distance on Stradivari’s other contraltos is around 47.5 mm.

The outlines of the ‘Kux’ (red) and the ‘Archinto’ (blue): the soundholes of the ‘Kux’ are set slightly wider and slightly higher than the other contralto violas to accommodate the d’amore’s six-string bridge (outlines taken from photographs).

The original head of the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ is an ingenious design which shows Stradivari’s pragmatism, mechanical creativity and restless innovation. The head of a viola d’amore needs to accommodate tuning pegs for six main strings and six ‘sympathetic’ strings.[22] This makes most d’amore heads tenuous, slender and fragile. In place of the typical single-trench pegbox, Stradivari instead created a stronger and more compact design with two parallel trenches on either side of a shared internal pegbox wall. Two courses of strings are set side by side, and the outer walls each have holes for six pegs while the shared inner wall has twelve into which all twelve pegs terminate.

The original head of the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ is an ingenious design which shows Stradivari’s pragmatism, mechanical creativity and restless innovation

The typical pegbox of a viola d’amore is long, slender and fragile. The pegbox of the Contreras d’amore on the left has been replaced and the head of the Ferdinando Gagliano in the center is noticeably warped. Stradivari’s ingenious design (right) set two courses of strings in parallel trenches with all twelve pegs terminating in the central pegbox wall. This innovative design is much more stable than the traditional d’amore head model. Collection Musée de la Musique, Paris, inv. no. E.484. Photo: Claude Germain © Cité de la Musique – Philharmonie de Paris.

The head terminates in a shield; strong black chamfers mark the outline; the central wall of the pegbox also has heavy chamfers but without the black accent. At the base of the pegbox where the upper nut was attached, glue residue is visible at the left and right sides but not in the center, marking the channel through which the sympathetic strings passed. A small gap at the base of the pegbox walls, no wider than a saw kerf, held the secondary nut for the sympathetic strings.

A small gap at the base of the pegbox walls, no wider than a saw kerf, held the secondary nut for the sympathetic strings. Collection Musée de la Musique, Paris, inv. no. E.484. Photo: Claude Germain © Cité de la Musique – Philharmonie de Paris

Interestingly, there are two patterns in the Museo del Violino collection that are compatible with this double-pegbox design. MS371 and MS372 are paper templates for a neck and pegbox about the same size and shape as the one in the Paris museum. I’m curious about the small dots drawn onto both patterns that indicate the placement and spacing of peg holes. Stradivari’s templates for violin, viola and cello heads typically don’t have indications for the peg holes. The templates for his six-string viola da gamba (1684, MS250), his seven-string bassa de viola alla Francese (1701, MS318) and these two templates for a possible viola d’amore, however, all have inked dots to show where peg holes should be placed. And fascinatingly, one of the patterns, MS371, has an added set of inked dashes or compass arcs in between each dot. My theory is that MS371 is the pattern that Stradivari used to lay out the head of the ‘Kux’ d’amore: the dots indicated the position of peg holes on one side of the double-trench pegbox and the dashes indicated the position of the peg holes on the other side.[23] Later this month I will meet with Jean-Phillipe Échard, the curator of the Musée de la Musique and we will re-introduce the ‘Kux’ and the scroll.

Paper templates for pegboxes that could accommodate twelve strings with Stradivari’s ingenious design (MS371, left and MS372, center and detail at right). MS732 seems to have alternating dashes and dots which could indicate the placement of pegs for two courses of strings. © Museo del Violino, Cremona.

At the Museo del Violino, there are also patterns for a six-string tailpiece (MS343) and for a viola d’amore bridge with a cut-away heart through which sympathetic strings could pass (MS351). Even if these patterns weren’t specifically made for the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’, they give us an idea of Stradivari’s original thinking behind these instruments and what they and their fittings would have looked like. It is an immense treasure to have these Stradivari relics preserved in the Museo del Violino as a reference for posterity.

Patterns for a six-string tailpiece (MS343) and a bridge with space for a course of sympathetic strings (MS351). © Museo del Violino, Cremona.

• • •

Making the D’Amore into a Viola

As Cozio noted in 1801, a viola d’amore was infinitely more useful when it had viola shaped corners and soundholes.

A typical viola d’amore has a flat back, blunted corners, sloped shoulders, pointed sound-holes, a square edge and an ornamented ‘rosette’ in the center of the top to increase its resonance. The conversion of a typical d’amore into a viola would be a challenge for even the most ambitious of luthiers. But because the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ resembled a viola so closely, and because it was in fact built on Stradivari’s viola form, the conversion was actually quite simple.

Traditional violas d’amore. Converting an instrument without violin-style corners and with ‘flaming-sword’ sound holes would be much more difficult and destructive.

We assume that the original back to the ‘Kux’ was flat as this was the convention for violas d’amore. We also assume that the back was made with a canted ‘fold’ or ‘step’ in the upper bouts. By examining the lower ribs and the corner blocks of the ‘Kux’ we can confirm that the rib-height had indeed been reduced by taking material from the plane of the back.[24] The original ‘fold’ was removed from the rib structure, and the upper ribs were refashioned to remove the ‘shoulders’ and glued onto a conventional upper block. The current rib heights taper from 36.5 mm at the lower block to 35.5 mm at the neck. The original ribs of the d’amore would probably have been in excess of 50 mm.[25] Stradivari’s patterns for a soprano d’amore specify a rib height of 59 mm.[26]

The upper bouts of the table were also slightly modified to trim the shoulders, and the upper edge of the top was reinforced on either side of the neckset. The flat back was discarded and a new arched one was made to match the outline of the top. Vuillaume chose an exceptional piece of deeply-flamed maple and skillfully imitated the master’s style. The reddish-brown varnish, gently antiqued, is a near perfect match to that of the top and ribs.

It can’t be overstated how fortunate we are that Stradivari’s original design was closer to a viola than a d’amore. If the original instrument had been cornerless, adding viola-shaped corners would have been ungainly and forever altered the outline. Moreover, it is fortunate that the sound-holes of the ‘Kux’ were made as viola soundholes. In the Museo del Violino collection there are also patterns that Stradivari made for sound holes in the ‘flaming sword’ style of traditional viols.[27] Any attempt to transform these into f-hole shapes would have resulted in a travesty!

Left: Stradivari’s paper templates for traditional ‘flaming sword’ style sound-holes (MS349 and MS350) and a viola d’amore by Jose Contreras made in 1753. Converting these sound holes to violin style f-holes would be a travesty. Paper templates © Museo del Violino, Cremona.

The final modification that Vuillaume would have had to consider was the replacement of the d’amore scroll. The head he chose—made by Nicolo Amati in c. 1620—is functionally adequate and properly proportioned, but it’s the one aspect of Vuillaume’s conversion that continues to puzzle me. Vuillaume was an accomplished and proud imitator of Stradivari. The back he made for the ‘Kux’ is nearly flawless stylistically and has a beautiful varnish that closely matches that of the top. Why didn’t he put in the extra effort and carve a replica head for the ‘Kux’ in the style of Stradivari?

Vuillaume was a gifted and accomplished copyist of Stradivari. Why didn’t he make a replica head for the ‘Kux’ in the style of Stradivari? The 1696 ‘Archinto’ Stradivari (left), the 1865 ‘Chimay’ Vuillaume viola (center) and the c. 1620 Amati head that Vuillaume joined to the ‘Kux’ (right).

Vuillaume was an accomplished and proud imitator of Stradivari. Why didn’t he put in the extra effort and carve a replica head for the ‘Kux’ in the style of Stradivari?

I also don’t have a good explanation as to why the head in the Musée de la Musique’s collection exists without its original neck. Why was it decapitated so aggressively as if preparing it for a graft? I would have expected that Vuillaume would have preserved the neck and the neck-root; but unfortunately for us, he lopped off the scroll under the chin.

And lastly, there is the question of the label. It’s impossible to know for sure who inserted the facsimile label of 1715 but it seems likely that it was Vuillaume since, by 1862 at the Castelbarco auction, it was already in place.[28] Perhaps the original Stradivari label (which would have been dated around 1720) was useful in some other way or preserved simply as a specimen. Around the time that Vuillaume performed the conversion of the ‘Kux’, he was in possession of possibly the ultimate example of Stradivari, the 1715 ‘Alard’. Perhaps the similarity of the red varnish on these two instruments was his inspiration to ascribe the ‘Kux’ to the same year.

• • •

The Twelve Stradivari Violas

There are twelve surviving Stradivari violas built over six decades. The earliest was made when the maker was in his twenties and the last, in his late eighties.

In the Museo del Violino there are three viola forms from the Stradivari workshop. The first form (MS55) was developed in or before 1672 and is the model on which the ‘Mahler’ viola was made. The second and third forms, designated by Stradivari as T.V. (MS229) and C.V. (MS205) (tenore and contralto viola), were made in 1690.[29] The T.V. resulted in an instrument with a back length of almost 48 cm; the violas made on the C.V. and the first form are around 41 cm long. The 1690 ‘Medici Tenore’ is the only surviving instrument built on the T.V. form. The front of the c. 1695 ‘Axelrod’ viola in the Smithsonian appears to have been reduced from a tenore model. The C.V. form was by far Stradivari’s most productive: nine of the twelve surviving violas, including the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’, were made on the C.V. form.

Stradivari’s three viola forms, MS55, MS229 (T.V.) and MS205 (C.V.) (illustrated to scale). © Museo del Violino, Cremona.

Ten of the violas are complete in all parts. The c. 1720 ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ was adapted from a cornered viola d’amore. The c. 1695 ‘Axelrod’ was reduced from a larger instrument and fitted with a replacement back. Of the ten violas with original scrolls, all but the c. 1734 ‘Gibson’ have a stepped pegbox.

The C.V. form was by far Stradivari’s most productive: nine of the twelve surviving violas, including the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’, were made on the C.V. form.

There is only one surviving decorated viola, the 1696 ‘Spanish Court’. A tenore viola originally belonging to the Spanish consort is thought to have been lost in the 19th century.

All but two of these violas are currently in the possession of foundations or state owned collections.

| 1672 | Mahler | Habisreutinger Foundation, Switzerland |

| 1690 | Medici Tenore | Istituto Cherubini, Italy |

| 1690 | Medici Contralto | Library of Congress, USA |

| c 1695 | Axelrod | Smithsonian Institution, USA |

| 1696 | Archinto | Royal Academy of Music, England |

| 1696 | Spanish Court | Royal Palace, Spain |

| 1715 | Russian | Russian State Collection, Russia |

| c 1719 | MacDonald | Private Ownership |

| c 1720 | Kux, Castelbarco | Private Ownership |

| 1727 | Cassavetti | Library of Congress, USA |

| 1731 | Paganini, Mendelssohn | Nippon Foundation, Japan |

| c 1734 | Gibson, Saint Senoch | Habisreutinger Foundation, Switzerland |

• • •

Special thanks to Carlo Chiesa who helped solve several mysteries as usual, to Jean-Phillipe Échard for his information on the head in the Musée de la Musique and to Ruprecht Kamplah whose book on Wilhelm Kux was particularly useful.

Notes:

[1] Échard, Jean-Philippe, Stradivarius et la lutherie de Crémone, Éditions de la Philharmonie, Paris, 2022, p 81-83.

[2] Letter from Paolo Stradivari to G. B. Guadagnini, March 2, 1775, The Carteggio of Count Cozio, Cremona, Biblioteca Statale.

[3] Ibid “…bellissimo e perfettissimo istrumento.”

[4] Letters from Count Cozio to Antonio II Stradivari, July 4 and July 20, 1801, The Carteggio of Count Cozio, Cremona, Biblioteca Statale, “…due viole d’amore intatte, costruite da suo nonno.”

[5] It’s unlikely that Cozio received a reply to his letter as Antonio II Stradivari died on 7 August 1789.

[6] “P.S. [ho omesso aggiungere] che mi intendo che gli occhietti osian[o] SS delle due viola siano della forma di quelle delle viole ordinarie da quattro corde, come vorrei farle ridurre, mentre altrimenti non mi convengono [acquistarle] a [questo] prezzo.”

[7] In their 1902 monograph on Stradivari, the Hills mention the ‘Kux’ and one other converted d’amore that was in the possession of the violin maker in Nancy, Charles Jacquot, p 227.

[8] Letter from Count Cozio to Gaetano Persico, September 30, 1804, The Carteggio of Count Cozio, Cremona, Biblioteca Statale.

[9] https://tarisio.com/cozio-archive/browse-the-archive/owners/?Entity_ID=1776

[10] Fetis, François Joseph, Notice of Anthony Stradivari, the Celebrated Violin-Maker, London, 1864, p 97.

[11] The Castelbarco sale was significant in that it was an Italian collection yet sold in London rather than Paris or elsewhere on the continent.

[12] This is further corroborated by the W. E. Hill & Sons Business Records which recalled in 1897 that the viola had belonged to “either the Plowden or Goding collections.”

[13] The original document is preserved in the British Library, London. A facsimile is reproduced in Music at Auction by James Coover, 1988.

[14] The Business Records of W. E. Hill & Sons (unpublished).

[15] Ibid.

[16] Kamlah, Ruprecht, Joseph Joachims Geigen, Ihre Geschichten und Spieler, besonders der Sammler Wilhelm Kux, Palm und Enke, 2018.

[17] Ibid, p 154-155.

[18] Ibid, p 159.

[19] Ibid, p 159.

[20] Rembert Wurlitzer & Co., Workshop Records, unpublished.

[21] The Dalla Valle Collection was passed from Paolo Stradivari to Count Cozio to the Marquis dalla Valle to Giuseppe Fiorini and eventually to the city of Cremona. The collection is now housed in the Museo del Violino. An excellent 2016 publication from the Museo del Violino, Antonio Stradivari, disegni | modelli | forme, Cremona, Museo del Violino, edited by Fausto Cacciatori, includes a DVD with images of these forms, models, tools and drawings.

[22] In the 18th century the d’amore had six+six strings, in later centuries, some instruments were made with seven+seven.

[23] MS371 appears to have been shortened or grafted onto a different paper neck pattern obscuring the last two markings.

[24] The lower block and the four corner blocks appear to be original. The table-side c-bout linings are mortised into the corner blocks in the typical Stradivari manner but the back-side linings abut the block, indicating that the blocks were lowered by taking material from the plane of the back.

[25] In the lower block, an earlier end-button hole is capped and off-center; if it were equidistant from the top and back plates, the rib height at the lower block would have been 52mm.

[26] Cacciatori, Fausto, Antonio Stradivari, disegni | modelli | forme, Cremona, Museo del Violino, 2016, p 181.

[27] MS349 and MS350.

[28] Coover, James, Music at Auction, Harmonie Park Press, Warren, Michigan, 1988, p 186.

[29] Inked inscriptions to the upper bouts of the C.V. and T.V. forms tell us that they were made in 1690 ‘especially for the most serene Grand Prince of Florence’ (Forma nova … fatta Ha Posta per Il ser.mo Gran Principe di Fiorenza). The inscriptions to the lower bouts are controversial and were probably added later, and not by Stradivari. The paper templates and designs related to these two forms are dated in the maker’s hand, 4 October 1690.

References:

Cacciatori, Fausto, Antonio Stradivari, disegni | modelli | forme, Cremona, Museo del Violino, 2016.

Codazzi, Roberto; Manfredini, Cinzia, I Capolavori Cremonesi della Royal Academy of Music, Consorzio Liutai Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 2003.

Coover, James, Music at Auction, Harmonie Park Press, Warren, Michigan, 1988.

Échard, Jean-Philippe, Stradivarius et la lutherie de Crémone, Éditions de la Philharmonie, Paris, 2022.

Frazier, Brandon, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Gateway Press, Baltimore, 2007.

Hill, William Henry; Hill, Arthur Frederick; Hill, Alfred Ebsworth, Antonio Stradivari. His Life and Work (1644–1737), W.E. Hill & Sons, London, 1902.

Kamlah, Ruprecht, Joseph Joachims Geigen, Ihre Geschichten und Spieler, besonders der Sammler Wilhelm Kux, Palm und Enke, 2018.

Plowden, Walter F. C. Chicheley, Records of the Chicheley Plowdens, A.D. 1590-1913, London, 1914.

Pollens, Stuart, The Violin Forms of Antonio Stradivari, London, Peter Biddulph, 1992.

Rattray, David, Masterpieces of Italian Violin Making 1620-1850: Twenty-six Important Stringed Instruments from the Collection at the Royal Academy of Music, London, 1991.

Rembert Wurlitzer & Co., Workshop Records, unpublished.

Sacconi, Simone F., I ‘Segreti’ di Stradivari, Libreria del Convegno, Cremona, 1972

Sackman, Nicolas, “The letters inked on Antonio Stradivari’s moulds and the ‘analytical strategy’ employed in Antonio Stradivari: disegni, modelli, forme”, 2018

W. E. Hill & Sons, Business Records, unpublished.