It is difficult to overstate the importance of Dvořák’s B minor Cello Concerto in the history of the cello repertoire. Of course, this was not the first successful concerto to feature the cello as a virtuosic solo instrument; that had already taken place in the Baroque and early Classical periods. But during the late Romantic period, composers, for the most part, weren’t writing concertos for solo cello; instead they favored the violin, which was regarded as a more suitable instrument for a solo performance with orchestra. Beethoven, Brahms, Mendelssohn, and Schubert all wrote superb compositions for cello – sonatas, chamber works, and concertos with cello as a co-soloist – but none composed a solo cello concerto. Robert Schumann’s Cello Concerto op. 129 (1850) was never played publicly during the composer’s lifetime and remained virtually unknown for many decades. Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations (1877) and Saint-Saëns’s first Cello Concerto (1872) were ground-breaking works. But Dvořák’s epic Cello Concerto in B minor op. 120 (1894) went a step further: with it he demonstrated that the cello could sit at the front of the stage and cut through the roar of a modern orchestra just as well as a violin. The cello, he showed, could do so with virtuosity, charisma, and with a heroic, commanding presence.

Dvořák dedicated his monumental B minor Cello Concerto to the Czech cellist Hanuš Wihan whose cello, a rare and important instrument by Bartolomeo Tassini, is offered by Tarisio by Private Sale.

Hanuš Wihan was born on June 5, 1855 in Politz, a small Bohemian town first settled in the 13th century. He was, by all accounts, a prodigy. At thirteen, he entered the Prague Conservatory, where he was taught by František Hegenbarth, before moving to St. Petersburg to study under Karl Davïdov. By eighteen, Wihan was a professor at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, and a series of appointments in major European orchestras followed soon thereafter. [1] In his early professional years, Wihan forged close collaborative relationships with leading conductors and composers such as Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner. The young Richard Strauss dedicated his Cello Sonata, op. 6, to Wihan in 1883. [2] But by far the most significant alliance, and the one that would assure Wihan an enduring legacy, was with the composer Antonín Dvořák.

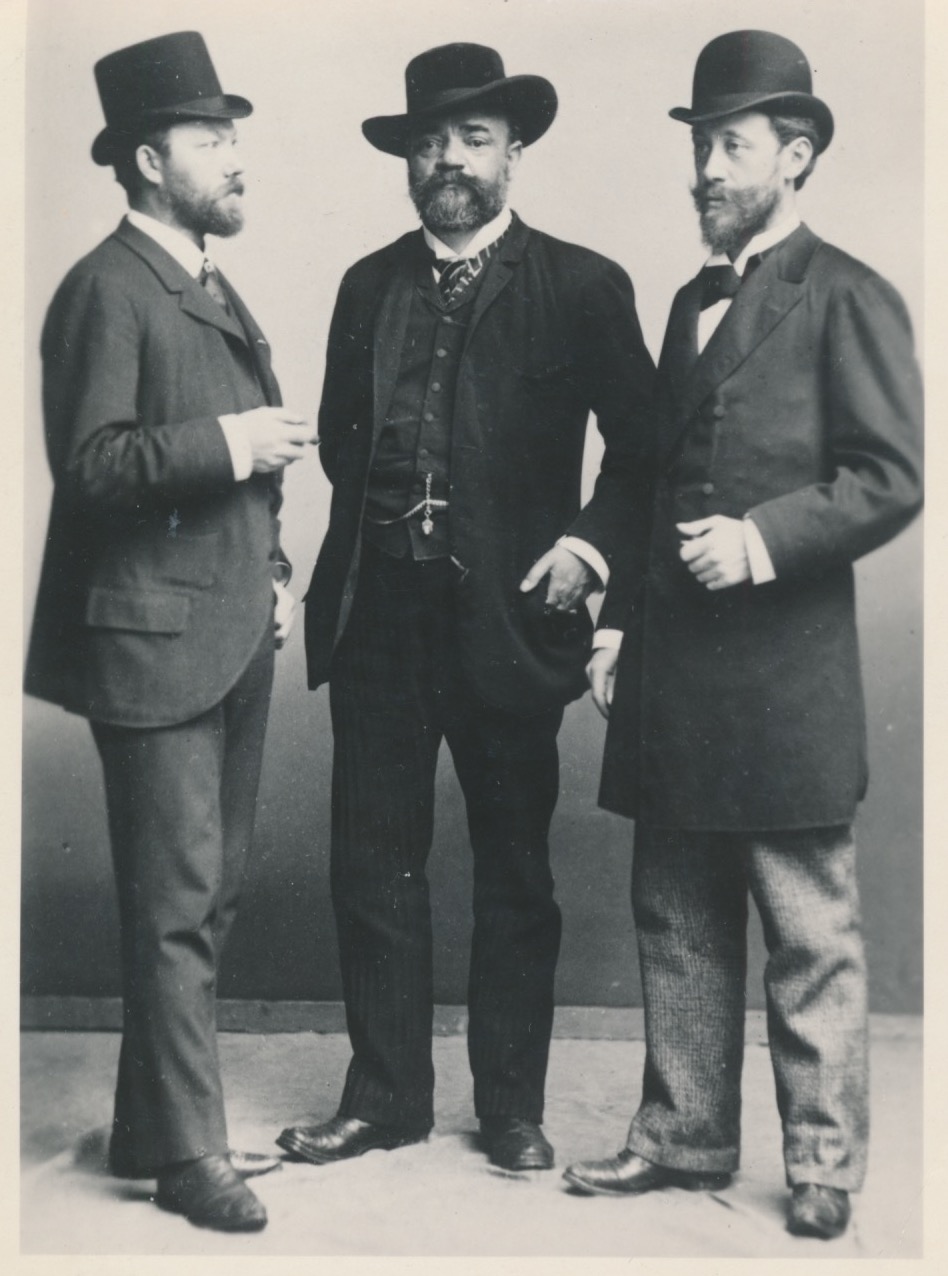

Hanuš Wihan, Antonín Dvořák, and Ferdinand Lachner (private collection)

Hanuš Wihan, Antonín Dvořák, and Ferdinand Lachner (private collection)

When the two met, Dvořák was fourteen years Wihan’s senior; nevertheless, the men formed a close friendship that would inspire the writing of Dvořák’s most important cello compositions. The beguiling cello part of the Dumky Trio, op. 90 (1891) and the cello transcription of Silent Woods, op. 68 (1891) were written with Wihan in mind, and Dvořák dedicated the Rondo, op. 94 (1894) and the B minor Cello Concerto, op. 104 to his friend and colleague.

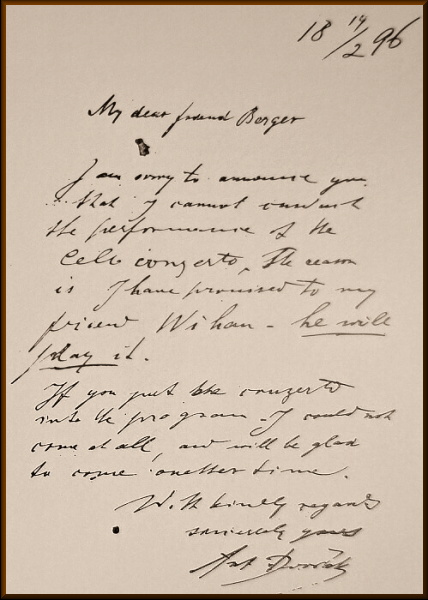

But it was the events leading up to the premier of the Cello Concerto in London in 1896 that permanently cemented their association. Although the Cello Concerto was dedicated to and intended for Wihan, the premier was given by the English cellist Leopold Stern who likely performed it on the 1684 “General Kyd” Stradivari cello which he had played since 1893. [3] It is true that Wihan and Dvořák had quarreled over the concerto; Dvořák accepted some suggestions while rejecting others, notably a cadenza that Wihan had written for the third movement. [4] But ultimately, the decision to appoint Stern arose from a scheduling conflict with Wihan’s quartet and was made by the London Philharmonic Society. Dvořák strongly objected at first but eventually acquiesced. In a letter dated February 14, 1896, just one month before the premier, Dvořák insisted that the premier must be made by Wihan: “I am sorry to announce [to] you that I cannot conduct the performance of the cello concerto. The reason is I have promised to my friend Wihan – [that] he will play it. If you put the concerto into the program, I could not come at all, and will be glad to come another time. With kindly regards, sincerely yours Ant. Dvořák.” [5]

Although Stern is credited with playing the orchestral premier, in fact, a performance had already been given at a private concert one year prior. With Dvorak himself accompanying, Wihan played an earlier version of the Concerto at the home of Josef Hlávka, a patron of the arts and music, in Lužany in September of 1895. [6]

“I am sorry to announce [to] you that I cannot conduct the performance of the cello concerto. The reason is I have promised to my friend Wihan – [that] he will play it. If you put the concerto into the program, I could not come at all, and will be glad to come another time. With kindly regards, sincerely yours Ant. Dvořák.”

As much as Wihan is connected to Dvořák, he also owes his legacy to the internationally successful Bohemian String Quartet. The quartet was established in 1891, and Wihan appointed his student, Otto Berger, as its first cellist. When Berger’s health declined prematurely three years later, Wihan replaced him, and served as the ensemble’s cellist until 1914. [7] During his twenty-year tenure, the quartet achieved worldwide fame.

Amongst the instruments played by the Bohemian String Quartet’s members, Wihan’s Tassini cello found itself in good company: Karl Hoffman, the first violinist, played the 1744 ‘Prince of Orange’ Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, while the second violinist, Josef Suk, played a 1683 Stradivari. [8] It was noted that the “adjustments and repairs” to the quartet’s instruments were “taken on by the violist, Herold” which is more than slightly concerning! [9]

The Bohemian Quartet in c. 1897 with Karl Hoffmann, Joseph Suk, Hanuš Wihan and Oscar Nedbal.

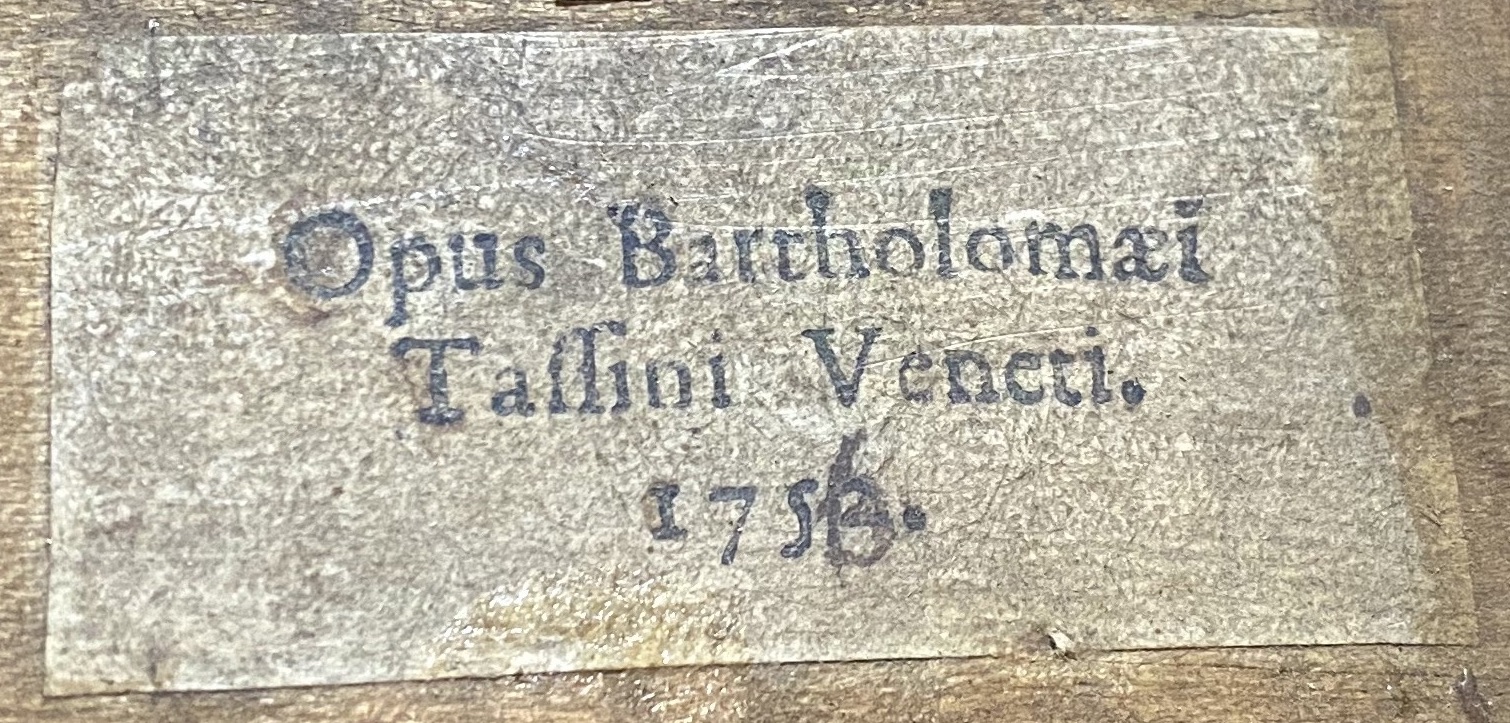

Tassini himself is somewhat of an enigma. Archival research has yet to produce any confirmation of his place of birth or death, or any significant events from his life. He is generally referred to as working in Venice, but that is not necessarily what is written on his labels. Part of the historical importance of this cello is that it is one of the few instruments by Tassini that bears an original label. Printed with text in Latin, the label reads, “Opus Bartolomæi Tassini Veneti 1756” (the work of Bartolomeo Tassini, of the Veneto, in 1756). In contrast, nearly all of the significant Venetian makers of the mid-18th century labeled their instruments, “fecit Venetiis” or “fece in Venezia” (made in Venice in Latin and Italian respectively). Tassini, on the other hand, isn’t saying “I made this in Venice”, but rather, “I am from the Veneto” and while this provides information concerning his citizenship and origins, it does little to clarify where he lived and worked.

For over a thousand years, the Veneto had been a commercial superpower, but by the 18th century, its influence was waning. The region comprised a large area which included cities as distant as Verona and Brescia. Although in decline, the Repubblica di Venezia was still a culturally and politically influential nation state in the mid-18th century. Given the specific phrasing of the label and the fact that nothing has been unearthed in the Venice archives regarding Tassini’s movements, it is possible that he might have lived and worked in a city which today wouldn’t be considered Venetian at all.

The appearance of the instrument is one of strength, precision and confidence

The other detail that makes me question Tassini’s location is the fact that his surviving cellos are of a different model than was fashionable in Venice during the 1750s. By the mid 18th century, Venice, like much of the rest of Italy, had all but abandoned the larger cello model. The immense 77 cm bassettos made by Mateo Goffriller had gone out of style, and the Venetian makers of the new generation, including Serafin, Bellosio, Deconet, and Busan, were producing cellos with a back length of 73.0 – 75.5 cm. The Wihan Tassini has been reduced slightly in the upper bouts, but the back length is still over 76 cm. I know of four cellos by Tassini and all four were originally of the large model [10] which is significant because few places in Italy at this time were making cellos of this size. [11]

The wood choice of this cello is first class. The handsome flamed maple used for the back is of the highest quality and indeed superior to much of what was used by other Italian makers by the mid 18th century. Likewise, the spruce is of top quality and the plentiful varnish is a rich golden orange-brown color. The model is broad but well proportioned with compact corners and a fluid outline. Overall, the appearance of the instrument is one of strength, precision, and confidence which suggests an accomplished craftsman and not a dilettante or a dabbling carpenter. It is difficult to reconcile such an advanced and successful instrument with Tassini’s seemingly limited output.

The soundholes are symmetrical and precisely executed, but their form is unusual. One has the impression that the outer and inner edges were drawn separately, or perhaps that the width of the stems came out wider than originally intended. The wings are modest and abruptly turn inward to form small upper and lower holes. The arching on this cello is magnificent and very well-conceived: absent are the steep curves and deep hollows that one finds in cellos with less advanced arching designs. The head is tall with a long pegbox and an open throat. Viewed from the front, the volute is narrow and delicate with a small rounded chamfer.

The original label dates the cello to 1756 but interestingly, the fourth digit of the label, the number “6”, is written in ink over a faint printed number “2”. [12] This label seems to have been originally intended to be used in the year 1752 and thus had to be altered for the years thereafter. Most classical Italian makers used labels with only two printed digits, a “16__” or “17__” that denoted the century; these could then be used over many decades. Tassini’s label with a fixed “1752” had an extremely limited lifespan. Even for a prolific maker, printing the full four digit year was ambitious. [13][14]

I know another Tassini cello from one year earlier which bears the same label but the paper has been cut just under the lower line of text, presumably to remove the 1752 date. The maker has written “1755” in ink in the space above the printed portion of the label. The practice of using a label with a fixed date was unusual to say the least and is even more curious given Tassini’s limited production.

The Bohemian Quartet c. 1910 Karel Hoffmann, Josef Suk, Jeří Herold, Hanuš Wihan and his Tassini (private collection)

The Bohemian Quartet c. 1910 Karel Hoffmann, Josef Suk, Jeří Herold, Hanuš Wihan and his Tassini (private collection)

According to Wihan’s descendants, this cello was purchased from Fridolin Hamma in Stuttgart around 1880. It can be seen in the earliest photographs of The Bohemian Quartet which were taken circa 1897. When Wihan died in 1920, the cello was kept in the family until 1955. It was then acquired by another important Czech cellist whose heirs now present it for sale.

Jason Price is Tarisio’s Founder, Director, and Expert.

Notes

[1] Robin Stowell (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Cello (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 69.

[2] With Strauss the relations were collaborative on multiple fronts. After dedicating his cello sonata, ‘Seinem lieben Freunde Herrn Hans Wihan’, Strauss promptly fell in love with Wihan’s wife, resulting in the breakup of their marriage.

[3] W. E. Hill & Sons. Business records. Unpublished.

[4] Jan, S., Smaczny, J. (1999). Dvořák cello concerto (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press), 90-92.

[5] “Concerto for Cello and Orchestra,” Antonin Dvorak, accessed on January 24, 2021, http://www.antonin-Dvořák.cz/en/concerto-for-cello2.

[6] See Margaret Campbell, The Great Cellists (London: Faber & Faber, 2011).

[7] Campbell

[8] See “Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, Cremona, 1744, the Prince of Orange, Wald, Hoffmann,” The Cosio Archive, accessed on January 24, 2021, https://tarisio.com/cozio-archive/property/?ID=42581, and “Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1683, the Suk,” The Cozio Archive, accessed on January 24, 2021, https://tarisio.com/cozio-archive/property/?ID=40740.

[9] Campbell

[10] One of these, uncut and bearing an original label dated 1755, has a back length over the arching of 77.2 cm.

[11] In Florence, Gabrielli and the Carcassi family made large cellos; in Rome, Tecchler and Platner made large model cellos up until about 1750; in Milan, Paolo Antonio and his son Pietro Antonio made a number of large cellos into the 1760s; in Ferrara, not far from Venice, Luigi Marconini was making large cellos as late as 1790.

[12] The date of 1756 is supported by dendrochronology, the use of which one can observe the most recent visible rings on the bass and treble sides corresponding to 1733 and 1740 respectively.

[13] My colleague Carlo Chiesa pointed out one other classical Italian label with the complete year printed, a label from the Testore family from 1764 which appears three times in the Cozio archives.

[14] Stradivari and Balestrieri both used a label with three printed digits at various points in their production, “166_” and “176_” respectively, which resulted in many decades of instruments with crossed out or modified 6’s.