This may be the only article you’ll ever read about a counterfeit Guarneri and a celebrity circus elephant. How can they possibly be related? Well, it just so happens that one of the most talented imitators (or forgers, if you prefer) of Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù had a career interlude training an unruly circus elephant named Mademoiselle D’Jeck.

Lot 59 in our March London auction was put together by the precociously talented violin maker, copyist and elephant trainer, John Frederick Lott II.

Born in London in 1804, John Frederick Lott II was the son and brother of violin makers John Frederick Lott I and George Frederick Lott. As a junior, John was known as Jack. His father worked for Thomas Dodd, and is especially known for his highly sought after double basses.

The Lott children started violin making early. At the age of thirteen, not long after his mother died and his father remarried, Jack left home and started an apprenticeship with violin makers William and Richard Davis. After a short time, Lott left the Davis workshop and made instruments which he sold through various dealers. But by around 1823, Lott had evidently lost interest in violin making and for the next two decades he traveled throughout Europe and America working an assortment of odd jobs including sign-writer, fireworks maker and, most notably, elephant trainer for a traveling circus.1

This twenty year interlude from violin making was documented by the English novelist and violin enthusiast, Charles Reade who was a friend of Jack Lott. Reade’s short novelette which was published in 1858, Jack of All Trades, is an colorful and somewhat fictionalized account of Lott’s adventures.

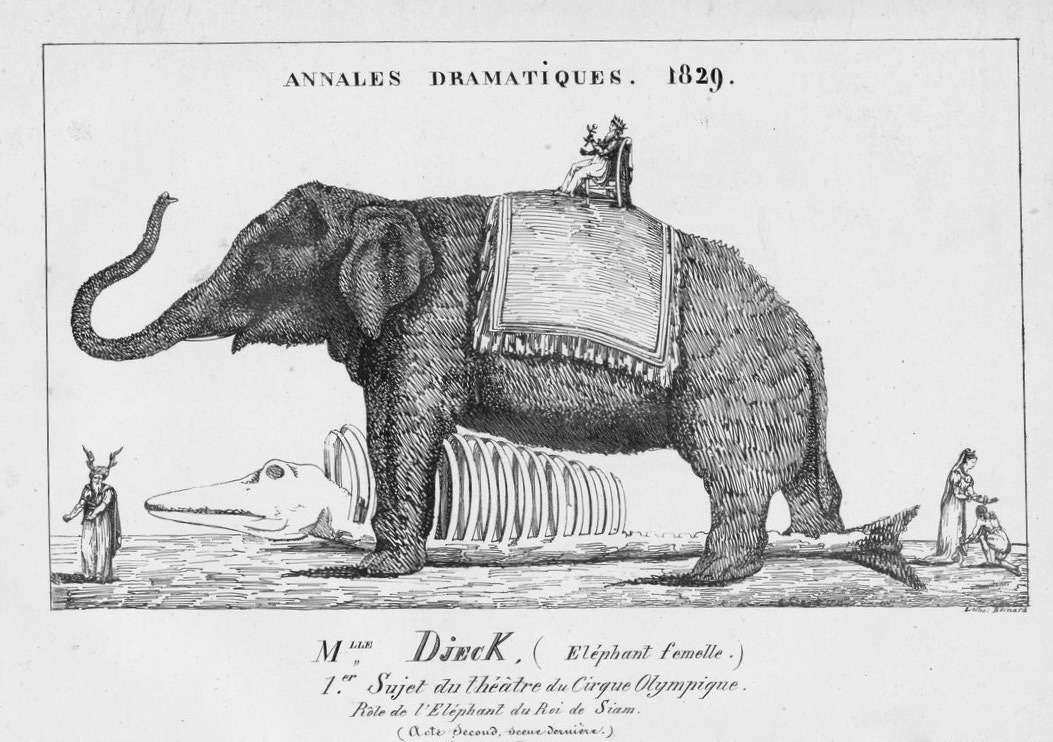

Mademoiselle D’jeck in the Annales Dramatiques 1829

Mademoiselle D’Jeck was one of the most famous performing animals of her day. She was born around 1806 in India or Sri Lanka and first appeared in Paris in July of 1829 with Antonio Franconi’s Cirque Olympique in a performance titled L’Éléphant du Roi de Siam (the Elephant of the King of Siam). D’Jeck performed throughout Europe and America with various circuses and presenters but her disposition was erratic and uncontrollable and she had a dangerous history of attacking bystanders. One newspaper of the time recounted, “At Morpeth she killed a man … returning to England she half-killed a baker. Going to France, she killed another man at Bordeaux. At another place she broke her keeper’s arm in two places. In Bavaria, she set her shed on fire.”2

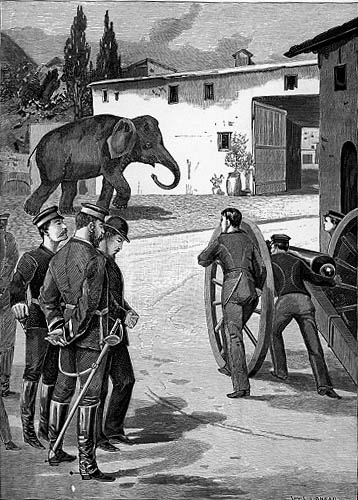

In the late 1820s, Jack Lott came to be the keeper and trainer of this badly-behaved elephant and for several years he traveled with her throughout Europe and America. His successes were many, but his final chapter with D’Jeck was undoubtedly a tragedy. In June of 1837, D’Jeck assaulted a priest in Geneva and broke several of his ribs. Subsequently, a trial was arranged, D’Jeck was found guilty and she was sentenced to death. A firing squad was assembled but the bullets couldn’t kill the great elephant and so a cannon was used instead. Adding horror to tragedy, it is said that the dead animal was promptly butchered and the townspeople feasted on elephant steaks.

A firing squad was assembled but the bullets couldn’t kill the great elephant and so a cannon was used instead. Adding horror to tragedy, it is said that the dead animal was promptly butchered and the townspeople feasted on elephant steaks.

An illustration of the death of D’Jeck in Jack of all Trades. When the firing squad’s bullets couldn’t kill her a “piece of cannon” was arranged instead. The poor elephant’s carcass was then butchered and eaten by the townspeople. As Reade put it, “Knives and scales went to work, and with the tears running down my cheeks, I sold her beef at four sous per pound.”

After putting circus life behind him, Lott returned to London and re-entered the violin trade. The instruments he made from around 1840 until his death in 1870 are among the finest English instruments ever made. He is particularly revered for his copies of Guarneri del Gesù which were often so successful that they were accepted by experts as the genuine article. He also frequently reworked parts of antique violins and assembled them into new instruments which were then passed off as authentic and complete examples. Just like del Gesù himself, Lott’s working style was spontaneous and bold and the instruments he made are seductive and alluring.

It can be debated whether he made his copies with the intention to deceive or rather as a challenge to display his skill. Like all talented forgers, his abilities can be admired even while his ethics are condemned.

Like all talented forgers, his abilities can be admired even while his ethics are condemned.

Lot 59 in our March sale in London is one such example of the copyist showing his exceptional skills and at the same time blurring the boundaries of imitation and forgery. The body of the instrument appears to be genuinely old, but has been reworked and manipulated to pass as the work of del Gesù. A dendrochronological analysis dated the latest ring of the treble side to 1756. The soundholes have been slightly altered and the scroll seems to be more recent than the rest of the instrument. The thick, dark-red varnish is a telltale sign of Lott’s handiwork. Throughout its history and until as late as the 1990s, this beguiling violin has been repeatedly bought, sold and certified as a genuine Guarneri.

In the 1880s it appeared with the London violin maker Frederick W. Chanot (1857-1911). In around 1888 Chanot sold it to his friend and associate, the Brighton violinist Cecil Marsland Gann (1862-1938)3. Chanot and Gann did frequent business together and their families were closely related: in 1921 Gann’s eldest daughter, Gertrude, married Chanot’s son, Francis. It’s difficult to accept that Chanot could have knowingly sold a forgery to his friend.

Cecil Marsland Gann, the first known owner of this violin, with his wife Charlotte and twelve of their fourteen children in c. 1905. (Photo courtesy of Kevin Chanot, Gann’s great-grandson).

In 1911 Chanot passed away and a year later Gann sold the violin to Frederic Flower (1853-1912), a “fiddle fancier” of Ramsgate. We find the first reference to this violin in the diaries of Arthur Hill on June 2, 1914 when it was brought to the W. E. Hill & Sons firm for their opinion. The Hills declared it “a composite fiddle, made up by Lott.”4

Four years later, the violin was presented again at Hills. It had since changed hands and was then owned by Captain Archibald David Edmonstone Craig (1887-1960) an amateur art dealer who had annoyed the Hills with his bargain hunting. Arthur reflected, “Capt. Craig … purchased a [so-called Guarneri] and has been ‘done’ over it. … a fine violin [is] not to be picked up as a bargain, the only way to obtain the real thing [is] to go to a reliable source, and pay the market price.”5 The diary entry from that day further noted that “there is a handsome coat of Jack Lott’s red varnish upon [the violin], the intense red colour he was so partial to.”7

Captain Archibald David Edmonstone Craig who, according to the Hills, never understood “that a fine violin [is] not to be picked up as a bargain, and the only way to obtain the real thing [is] to go to a reliable source, and pay the market price.”

A fine violin is not to be picked up as a bargain, the only way to obtain the real thing is to go to a reliable source, and pay the market price.

Either compensating for his mistake, or stubbornly refusing to accept it, Captain Craig next took his “Guarneri” on a tour of the capital cities of Europe to solicit certificates in its support. In London, Joseph Chanot backed the opinion of his brother Frederick with a certificate issued on December 10, 1919. In Paris, the son of Frederick’s paternal grandfather, Joseph Chardon, confirmed the “Guarneri” with a certificate issued on January 23, 1920. In Milan, Leandro Bisiach certified the “Guarneri’ on December 16, 1923. The certificates from these provincial authorities did little to change the facts of the matter: this violin, no matter how attractive, good-sounding and convincing it may be, was not a del Gesù.

Several years later the violin made its way to America where Captain Craig hoped to find a willing buyer. In New York, the violin maker Oswald Anton Schilbach (1862-1947) certified the “Guarneri” on March 19, 1930. Later that same year, the Simson & Frey violin company of New York, together with the Southern Californian Music Co. of Los Angeles, sold the “Guarneri” to the violinist Albert Carl Angermeyer Jr. (1892-1962). Shortly thereafter, Angermeyer discovered the controversy surrounding the violin and enlisted the help of the Berlin dealer, Philip Hammig, to resolve the situation. Hammig sent the violin to the Hills in London in September of 1930. Upon receiving their advice that the violin was “a composite one which had been varnished over by John Lott,”7 Angermeyer returned the violin to the dealers who had sold it to him for a refund.

The violin next appears – again selling as a “Guarneri” – when the Boston dealer John Gould sold it to J. Frederick Dalphe of Roxbury, Massachusetts on November 26, 1949.

Fast forward seventy years and the “Guarneri” appears again. But this time, the elephant in the room is being called out for what it is: a superb and successful forgery put together by one of the finest Guarneri copyists of all time.

Lot 59 in our March London auction was put together by the precociously talented violin maker, copyist and elephant trainer, John Frederick Lott II. It is on view in London until the sale on March 25.

Jason Price is Tarisio’s Founder, Expert and Director. Michael A. Baumgartner has spent many years researching Guarneri del Gesù and the histories of his surviving instruments for an upcoming publication.

- The British Violin. John Milnes, editor, British Violin Making Association, London, 2000, p 95.

- “Mademoiselle D’Jek” Judy; or the London Serio-Comic Journal. 30: 132. March 15, 1882.

- Gann was also the owner of the c. 1665-70 ‘Back’ Stradivari which Tarisio sold in March 2023.

- Diaries of Arthur Hill, unpublished. June 2, 1914.

- Diaries of Arthur Hill, unpublished. November 5, 1918.

- Diaries of Arthur Hill, unpublished. November 5, 1918.

- Diaries of Arthur Hill, unpublished. August 8, 1931.