The bows of Nikolai Kittel have long been regarded as mysterious. The origins of this reputation lie partly in the historical lack of information about Kittel,[1] as well as in the relative rarity of examples, and even more in their status as outliers: bows of non-French origin that rival those of the great François Xavier Tourte. Extravagant materials, exemplary workmanship and beauty of tone along with nimbleness of handling have earned Kittel bows a well-deserved reputation for excellence.

Ignorance of the life and work of Kittel once gave rise to skepticism in some circles. Authentic examples weren’t often seen, and in the absence of a body of work to consider, Western experts harbored understandable doubts. More recently the discovery of incontrovertible biographical information about Kittel as well as the dissemination of information about his bows has given rise to a growing appreciation of the extraordinary output of the Kittel shop.

Kittel cello bow, with typically fine gold and tortoiseshell mounts. The lavish quality of many Kittel bows probably reflects his access to wealthy clients at the Tsar’s court. Photos: Daniel Lane, Tarisio

Much of this work was done by the Kittel aficionado Kenway Lee (1950–2013). Lee’s highly informed passion for Kittel bows fueled a zealous research effort from the late 1970s that was only forestalled by his untimely death. His impact on our knowledge of Kittel cannot be overstated. He brought a number of unknown Kittel bows to light and catalogued known examples in detail. He also made several research trips to St Petersburg, managing to locate documents illuminating key elements of the Kittel story.[2]

Substantially informed by Lee’s research, the impressive 2011 volume ‘Nikolai Kittel’ by Joseph Gabriel, Klaus Grünke, and Yung Chin has done more than any other source to propagate a modern view of the life and output of Kittel.[3] Some of the details that have emerged as a result of this collective effort bear reiterating here:

Nikolai Ferdinandovich Kittel was born an Austrian citizen in 1805 or (more probably) 1806 in St Petersburg. The earliest known Kittel instrument is a cello in the Moscow State Collection dated 1827. In 1828 Kittel was appointed Instrument Maker for the Imperial Orchestra in St Petersburg; in 1835 he was appointed Purveyor to the Household of the Tsar. Kittel’s son, Nikolai Kittel Junior, was born in 1843 and in 1858 Kittel and his son traveled to Mirecourt, where Nikolai Junior remained for two years, studying violin making. Nikolai Senior died in 1868 and was succeeded in business by his son, who continued to run the company until the shop was sold in 1873.

Much about the production of Kittel bows still remains a matter of conjecture, however, and ongoing research is needed to answer lingering questions.

The extent to which Kittel bows were actually made by Kittel himself is unclear. Looking to a contemporary model, the atelier of Jean Baptiste Vuillaume, we think it likely that the Kittel workshop followed a similar system.

Vuillaume was trained as a violin maker and yet his workshop produced bows of high quality, sometimes to specifications provided by Vuillaume, and (like Kittel) branded with his name. Vuillaume employed some of the most esteemed bow makers of the day, including at least four Germans. Had the Vuillaume atelier produced only a handful of violins, as with Kittel, he might easily be known to posterity as a bow maker, just as Kittel is today.

But Vuillaume was even more renowned for his violins, employing a number of the best violin makers available to construct instruments to his specifications, generating a vast output of high quality. All the craftsmen employed by Vuillaume produced their best work for him. In many cases, their subsequent work never approached the level achieved for Vuillaume. The ability to draw the best out of his craftsmen may be Vuillaume’s most enduring legacy and helps to explain why today a Derazey or a Grandjon violin brings a fraction of the price of a fine J.B. Vuillaume, even though we know that both these makers had a hand in some of the most desirable Vuillaume instruments.[4]

We regard the Kittel legacy in a similar light to that of Vuillaume. From our study of authentic examples over decades, we have come to conclude that as many as four to five skilled artisans had a hand in the crafting of Kittel bows. While it is possible that one of these artisans was Kittel himself, we are unaware of clear evidence either way. Regardless of who might have been responsible for the production of Kittel bows, the standard remained consistently high throughout, indicating rigorous production oversight.

Heinrich Knopf for Ludwig Bausch c. 1860–1869

As noted by Gabriel, Grünke and Chin, the work of the German maker Heinrich Knopf (1839–1875) is evident in some bows from the Kittel atelier. Given Knopf’s age we presume he worked on Kittel bows in the shop’s last period of activity, probably starting in the early 1860s and ending when the shop was sold in 1873. For some decades before, and perhaps concurrent with the Knopf production, the excellent work of several other as yet unidentified craftsmen is evident in the output of the Kittel atelier, but whether or not any of the bows were produced off the site of the shop remains unproven.

Nikolai Kittel c. 1865–1870 (showing the hand of Heinrich Knopf)

Particularly with the frogs, buttons and work at the butt end of the sticks, we observe consistent details in the Kittel production from Knopf and other craftsmen alike. We don’t find these distinct ‘Kittel’ features on bows by Knopf bearing the brands ‘H. Knopf, Berlin’ or ‘L. Bausch, Leipzig’. Further, we note that regardless of whether they show the hand of Knopf, authentic Kittel bows consistently display a markedly higher standard in terms of materials, workmanship and playing qualities. The consistency of the Kittel output over more than four decades would seem to bear out that Kittel himself was responsible for providing special materials, detailed and distinctive specifications, and maintaining high standards for the bows that bear his name.[5]

We are aware of only three instruments by Kittel, although we presume others exist. Still, the absence of a larger surviving group of instruments by Kittel calls into question any assertion that Kittel could have made a living as a violin maker without pursuing ancillary sources of income. As the production of bows was relatively small, we are left to wonder how the Kittel atelier was sustained economically. One clue may lie in James Fleming’s 1892 description of Kittel as “A fine repairer, and also an exquisite bow maker.”[6] That Kittel is listed as a repairer first and a bow maker second may indicate the degree to which repairs and restoration played a role in the revenue stream of his shop.

As an employee of the Tsar, Kittel would have had access to many wealthy potential customers among the dignitaries and noblemen who frequented the court, and the lavish quality of Kittel bows is apt for patrons of elevated status. It seems easy to imagine that Kittel would have used this to advantage beyond selling his own products. That Kittel was at least occasionally a dealer in important instruments can be gleaned from an entry in an 1886 catalog of the Parisian expert and dealer Charles-Eugene Gand, describing the ‘St Senoch’ Stradivari cello of 1696 as ‘Ex Kittel’.[7] It wouldn’t surprise us to learn that Kittel had a hand in the transactions of other important instruments. Although nothing of that nature has come to light so far, revenue from brokering instruments would help to explain how Kittel could have maintained a shop in an auspicious location in St Petersburg with such a limited production of bows.

Early reception of Kittel bows

Nikolai Kittel c.1860

A favorable early reception of bows from the Kittel atelier must have contributed to their subsequent reputation. The violinist Henri Vieuxtemps toured Russia twice and finally settled in St Petersburg as Soloist of the Imperial Theater from 1846 to 1851. Invoices from the Kittel atelier and proof of Kittel’s appointment as Musical Instrument Purveyor to the St Petersburg Court in 1835[8] confirm that Vieuxtemps’s extended term in St Petersburg came during a period in which the Kittel atelier was thriving. This lends credibility to the claim by an early Kittel researcher, Evgenji Vitachek, that Vieuxtemps owned six Kittel bows.[9] Given that Vieuxtemps’s career afforded him access to the best violins and bows in the world, his choice to play Kittel bows must have enhanced their reputation.

The Hungarian-born violinist Leopold Auer served as concertmaster of the St Petersburg Imperial Theaters, and he taught at the St Petersburg Conservatory for nearly 50 years, from 1868 until 1917. Auer’s tenure in St Petersburg overlapped with the last period in which the Kittel atelier was active, from 1868, when Nikolai Kittel Junior succeeded his father, until it closed in 1873, and it seems likely that Auer would have met Nikolai Junior during that period. The Auer class at the conservatory served as a training ground for some of the most influential violinists of the day, including Heifetz, Milstein and Elman. As the leading violin pedagogue of his generation, Auer would have been in a position of great influence regarding the equipment choices of his students.

Nikolai Kittel c.1860

Auer must have been aware of bows by Kittel soon after his arrival in St Petersburg in 1868, by which time they would already have had a local reputation for excellent design, superior finish and unsurpassed functionality. Eventually Auer himself did own Kittel bows, arriving in the US in 1918 with two examples.[10] Auer also made a gift of a Kittel bow to his pupil Jascha Heifetz, who was quoted as saying that he preferred the Kittel that Auer had given him above all other bows.[11] This did much to affirm the mystique around Kittel bows, given Heifetz’s overwhelming influence on string playing in the 20th century and beyond. Having ourselves had the opportunity to study the Heifetz Kittel bow at length, we can confirm its authenticity. There is substantial photographic evidence to suggest that Heifetz used his Kittel bow extensively.

Writing in 1966, the violin pedagogue Harvey Whistler offered anecdotal accounts of Vieuxtemps touring America with his Kittel bows, and of other important contemporary artists who favored Kittel bows, including the Russian cellist Karl Davidoff, Alexander Zarzycki, a professor at the Warsaw Conservatory, and Apollinaire de Kontski, Vieuxtemps’s successor in St Petersburg. Whistler claimed that in all probability 75% of the world supply of Kittel bows was to be found in the US. More colorful than scholarly, Whistler’s anecdotes were published without citation but probably reflected a fair amount of truth about the history of Kittel bows.[12]

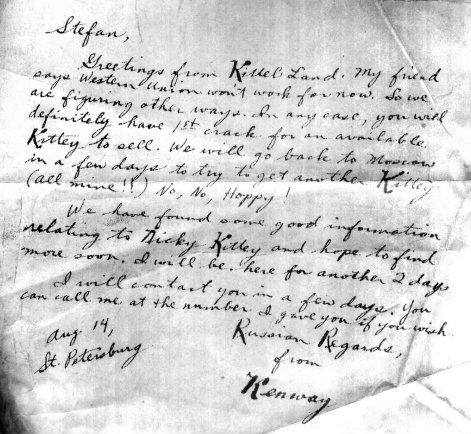

In 1995 Kenway Lee sent a series of faxes from St Petersburg, one of which is reproduced here. Alongside a display of characteristic whimsy, it offers a tantalizing whiff of new discoveries. Some of the pertinent material that Lee found in Russia remains unpublished and Kittel admirers can only hope that future research will yield answers to some of the lingering questions. In the meantime the extravagant wood, elegant workmanship and unique playing qualities that are the hallmarks of Kittel bows will continue to speak for themselves.

Published reception of Kittel bows

This chronological list of some of the published comments about Kittel bows suggest they were rare but admired in the West at the end of the 19th and into the 20th century.

Fax from Kenway Lee in 1995, hinting at new discoveries about Kittel

Fiddle Fancier’s Guide, James M. Fleming, 1892, p.234:

“This maker’s bows are about as nearly equal to Tourte’s as those of any maker that has lived since his day.”

The Bow, Its History, Manufacture, and Use, Henry St George, 1896:

The earliest writer on bows for stringed instruments as a stand-alone subject makes mention of Kittel, saying that he had never come across one but that by reputation they were “about as nearly equal to Tourte” and continues: “It is a pity they are not more plentiful if this is the case.”

Die Geigen and Lautenmacher vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, Willibald Leo von Lütgendorff, 1904:

“…the best violinmaker in Russia, who made fine bows as well.”

Nicholas Kittel, The Russian Tourte, Arthur Herman, The Strad, July 1931:

“[Kittel was] better than any other maker who tried to reproduce Tourte.”

“It was and is the ambition of every Russian artist to possess a Kittel.”

Rudolph Wurlitzer Catalog, 1931:

“[A] little known genius,” “…veritable gems. Nothing can be finer excepting only the best of Francois Tourte’s bows.” Prices for Kittel bows in this catalog ranged from $450 to $750, well above the value of bows by Dominique Peccatte on offer at $85 to $650.

Dictionnaire Universel Des Luthiers, René Vannes, 1951:

“Kittel… is known for good violins and especially good bows. He was nicknamed the ‘Russian Tourte.’ A violin bow in the collection of Lyon and Healy, Chicago was for sale for $350.00 in 1928.”

Universal Dictionary of Violin and Bow Makers, William Henley, 1957

“A German better known for magnificent bows. So finely constructed that he was often termed the ‘Russian Tourte’.”

Bows and Bow Makers, William Charles Retford, 1964

Reinforces Saint-George’s comments about the rarity of Kittel bows, and adds that the few he had seen did not look like German work.

Nikolaus Ferder Kittel: The Russian Tourte, Harvey and Georgeanna Whistler, Music Journal, May and September 1965 (repub. The Strad, May and July 1969):

The first article to widely disseminate a connection between Knopf and Kittel.

Notes

[1] Arthur Herman, The Strad, July 1931, p. 154: “It is Strange that we have so little factual information about Kittel’s life….we have only the meagrest smattering of biographical data concerning this most distinguished master of recent times.”

[2] “Nicolaus Kittel: The Russian Tourte” Kenway Lee, VSA vol. XIV, no. 2, 1995

[3] “The Bows of Nikolai Kittel” Joseph Gabriel, Klaus Grünke and Yung Chin, 2011

[4] J.B. Vuillaume Sa Vie et son Oeuvre, Roger Millant, 1972

[5] For a detailed technical analysis of Kittel bows, see Gabriel, Grünke and Chin, pp.29–80

[6] Fiddle Fancier’s Guide, James M. Fleming, 1892, p.178

[7] Catalogue descriptif des instruments de Stradivarius et Guarnerius del Gesù, Charles-Eugène Gand, p. 119

[8] Grünke, Gabriel and Chin, pp. 228–229

[9] Grünke, Gabriel, and Chin, p. 30, referencing notes of Evgenji Vitachek, pub. 1952

[10] The Violin, David Schoenbaum, 2013, p.311

[11] “An Interview with Herbert Axelrod” VSA vol. IV, no. 1, 1977

[12] Nikolaus Ferder Kittel: The Russian Tourte, Harvey and Georgeanna Whistler, Music Journal, Sept 1966