The history of Stradivari violas begins with an enigma. The earliest known example, the ‘Gustav Mahler’ of 1672, is a bit of an oddball. Perhaps the most unexpected of Stradivaris, it almost merits the description ‘ungainly’ within the company of all his other work. If it was from any other hand it would be a masterpiece: the workmanship is as fine and delicate as can be. But as it is, broad and squat in outline with awkward transitions in the curves, it might at first seem to represent the master’s discomfiture with the instrument, perhaps even a vague lack of interest in the awkward middle child of the violin family.

There has always been a question mark over his violas – do they really work? Do they have the profundity of the great Brescians? Are they a little too difficult to master? Well, too few players or listeners ever have the chance to really judge. Stradivari made only ten that we know of. Not a great deal more than the total number of his guitars and mandolins, set against a balance of at least 600 violins and 60 cellos that came from his workshop. But to be fair, the viola as an instrument had a difficult and obscure history before Stradivari, and the fact that these few exist at all is significant.

Stradivari’s earliest surviving viola, the 1672 ‘Mahler’, is something of an enigma. Photo: Jan Röhrmann

More photosSome of the earliest surviving instruments of the violin family are great tenors, made by the Amati family in Cremona, and in Brescia by Gaspar ‘da Salò’ and others. Their production of violins and violas is quite balanced, but after this initial burst, northern Italy seems to have become sated with tenors. If there was a golden age for the instrument, it may have seemed to be over by 1630. Violas make rare appearances throughout the 17th and 18th centuries in workshops from Venice down to Rome, where David Tecchler inscribed one of his violas (ID 42458) as ‘only the third I have had made’ just four years before his death in 1747. Matteo Gofriller was the only one of the classical Venetians to produce more than a pair of surviving instruments.

Part of the difficulty for makers was the changing role and definition of the instrument. Violas were made in two voicings, the large, 44 cm or more ‘tenor’ and the roughly 42 cm ‘contralto’. The smaller contralto is almost unknown in the early period – only one Gaspar, the c. 1580 ‘Kievman’, is presently known. Apart from two outstanding Brothers Amati contraltos from 1615 (the ‘Stauffer’) and c. 1620 and a few examples made by Maggini in the same period, they emerge only in the later 17th century, just when Stradivari was beginning his career. The ‘Mahler’ Stradivari is in a way the first of a new breed, perhaps more indicative of the visionary aspect of his work throughout his life, which constantly produced new ideas, models and levels of achievement, than any lack of interest in the viola.

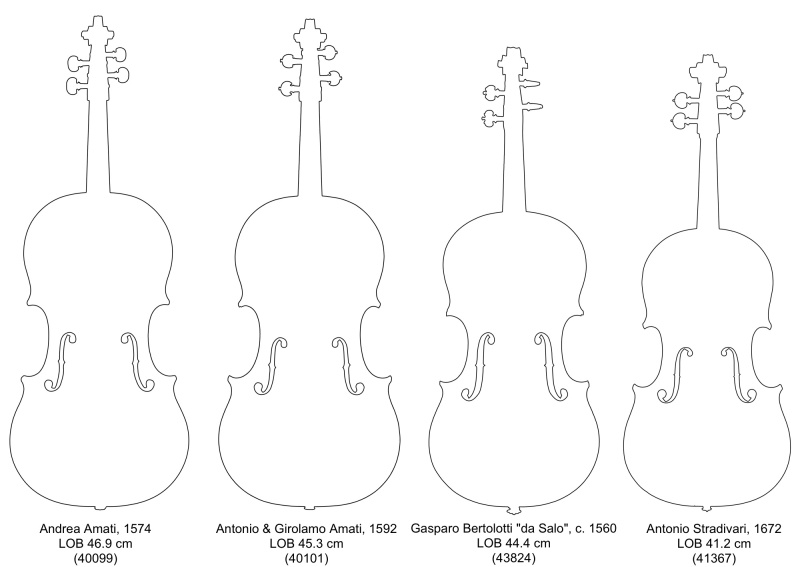

The outlines of four violas, showing the decrease in size from Andrea Amati’s tenore model to Antonio Stradivari’s contralto (images scaled to relative size)

To understand this requires a bit of musicological context. The viola has long been primarily a supporting instrument. But in the early 16th century in northern Italy the tenor part was central, taking the role of the male voice in instrumental music, with treble instruments providing decoration. Most early developments of the violin family in Brescia revolved around the larger instrument. This began to change in the second half of the century when Andrea Amati’s violas were made as essential parts of at least two commissioned sets, for Charles IX of France and Marguerite of Navarre, which contained large and small violins, large violas, and cellos. These sets, in the tradition of the royal courts and chapels of the 16th and early 17th centuries, had violas at their heart. But in the Italian baroque development of formal music, the viola lost ground. The most common sonata forms, ‘a solo’ or ‘a due’, comprized only one or two violins and basso continuo. Corelli brought to the fore the trio sonata, which still generally had no viola at all. Nor did the popular Concerto Grosso have much room for it. The ‘concertino’, the group of soloists, has no viola; one only appears in the supporting ‘ripieno’ group. Any formally composed music with a leading role for the viola was a rarity before 1700. But in France the court musician Jean Baptiste Lully maintained the older ‘Chapelle du Roi’ tradition through the greater part of the 17th century, which was arranged for five or six stringed parts including separate tenor and contralto violas. It was not until Bach that the viola returned to the foreground. The 6th Brandenburg Concerto, written in around 1718 with leading parts for two violas, might be seen as the liberation of the instrument.

It was not until Bach that the viola returned to the foreground. The 6th Brandenburg Concerto, written in around 1718, might be seen as the liberation of the instrument

We know that Amati and Gaspar exported their work beyond Italy. Their success depended on supplying the royal courts of Europe. Stradivari too won commissions from France and Spain, and these were for ‘sets’ of instruments, complete with violas. Out of all Stradivari’s violas, three are certainly associated with commissioned ‘sets’, made for the Medici in Florence and the Royal Court in Madrid. There is also documentary evidence of other sets which may have been made but not delivered, including those for King James II of England in 1682, and an order from the Duke of Savoy in 1685; it is possible that these were the origins of other violas, although none has been identified from this period.

The late violas are special cases, as we shall see, and only four are currently not definitely linked to large commissions. It is significant that from about 1710, the beginning of the golden period, there are no records of large-scale commissions from the Stradivari workshop. After the Austrian takeover of Cremona in 1702 in the War of the Spanish Succession, cultural and economic relationships shifted from Bourbon France and Spain to the Habsburgs, and this may have had a strong effect on Stradivari’s clientele. From the first decade of the 18th century he seems to have concentrated on making violins and cellos to the exception of virtually anything else, including his showpiece decorated work, which with only one exception dates from before 1709. After 1720, there is only a single viola that is a pure example of Antonio’s workmanship.

The head of the ‘Mahler’ has the wide-set eyes of a hammerhead shark, setting it apart from the rest of Stradivari’s work. Photo: Jan Röhrmann

When the viola did re-emerge in the late 17th century, it had been refined down to its sleeker, more manageable contralto form, with some loss to its lower register, but gains in the clarity and response in the treble range. The 1672 ‘Mahler’ was possibly the first contralto to be made in Cremona for over 50 years. In that period there is little evidence of violas being made at all, other than a handful of examples by Jacob Stainer and artisan makers north of the Alps.

The 1672 ‘Mahler’ was possibly the first contralto to be made in Cremona for over 50 years

Why did Stradivari decide to make such a thing as he was setting out to prove himself as a challenger to Nicolò Amati, the most famous luthier in the world? Whether through his own foresight and musical intelligence, or as the result of an individual commission from a player may never be clear. It is the only example known to exist from its wooden form (ms no.55) preserved in the Cremona Museo del Violino, which tantalizingly shows more wear and tear than would be expected from just one use. The instrument itself is made from poplar wood, a plain, unprepossessing choice, and spruce with twisted grain. And the head, also of poplar, is strange. It looks out of proportion to the body and has the wide-set eyes of a hammerhead shark, aspects which make it stand out from the rest of Stradivari’s production, and make it uniquely fascinating. It is no showpiece, but a fine, practical player’s instrument.

In fact much of his work from this early period seems tentative, perhaps unsurprisingly. It shows a maker finding his own way, not following the dictates of a particular master. The viola also fits well within the extraordinarily broad range of instruments he made then, from guitars to harps – and countless other types of stringed instruments are recorded just as draft designs on paper. He was exploring a vast range of possibilities and this small viola was just one of many. But after the ‘Mahler’, similar contraltos by Andrea Guarneri appear, and as we shall see in part 2, Stradivari embarked on his fitful career of viola making which was devoted, with one exception, to the smaller model.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.