I know that not everyone loves graphs and data. Personally, I often find data dizzying and glaze over, so if charts and percents aren’t your thing, here are some good viola jokes instead. But if you do like charts, buckle-up because I made a lot of them… The goal here was to illustrate trends and tendencies in the production of violas over the past five-hundred years. There aren’t many surprises: we all know there are fewer violas than violins and cellos, that violas come in different shapes and sizes, that some makers specialized in violas, and others wouldn’t touch them with a ten foot chisel. I hope that seeing these graphs can give a new dimension to the much loved instrument that burns longer than the violin.

Violas as a percentage of total instruments ever made

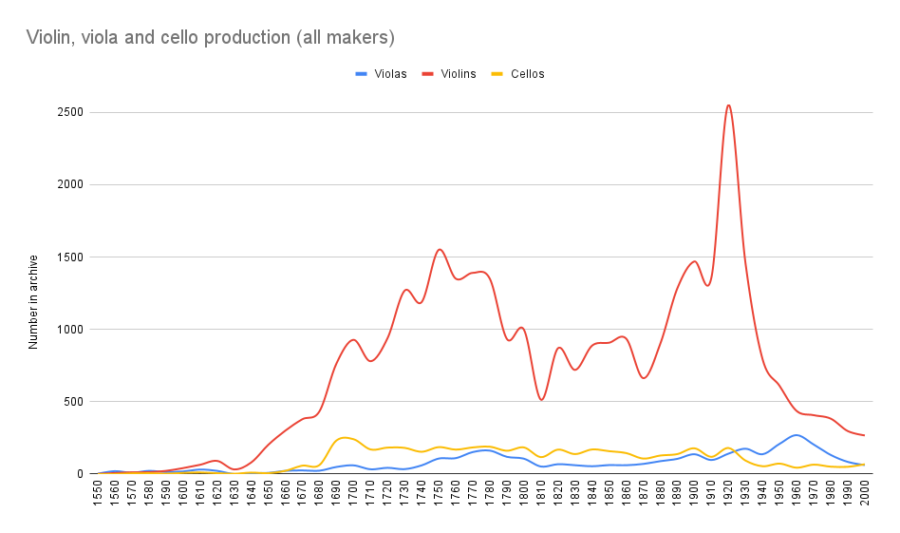

This first graph shows the total number of instruments built per decade worldwide since the beginning of violin-time: the red line is violins, blue is violas and yellow, cellos. A few observations:

-

- Instrument making all across Europe grew rapidly in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

- The number of violins made in 1750 was nearly ten times the number made a century earlier.

- Viola and cello production also increased during this period but not as rapidly as violins.

- The dip at around 1630 represents the plague years.

- The decline over the last fifty years of the chart represents a data flaw – instruments made during this time have not fully arrived on the secondary market.

- Global violin production peaked from 1880-1930 with centers of mass production (Mirecourt, Markneukirchen) added to traditional artisanal workshops.

- Although violin production increased greatly over the past three hundred years, viola and cello production stayed relatively constant.

- There are two periods of noticeable growth for viola making: the end of the 18th century and the middle of the 20th.

Although violin production increased greatly over the past three hundred years, viola and cello production stayed relatively constant.

(The data in this article come from the Cozio archive. The information in the archive is extensive and rich and, for the most part, very accurate. Nevertheless there are a few biases and flaws that I have taken into consideration including: the attrition of instruments over time, historic mis-attributions and cluster dating around circa dates.)

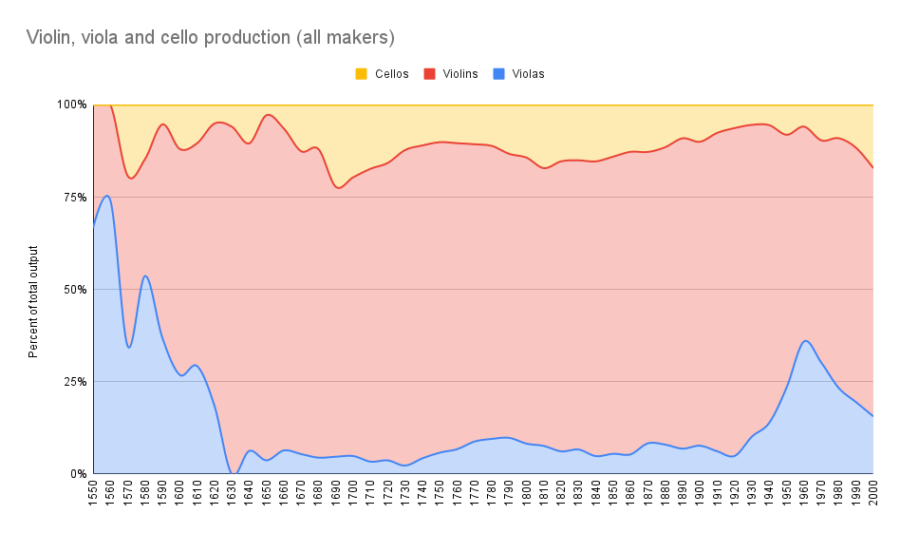

Here again is a graph of the total global output of instruments, but this time violins, violas and cellos are represented as a percentage of the total yearly global output.

-

- What’s fascinating here is to see that violas were produced in much higher percentages in the 16th and early 17th centuries relative to violins.

- Before 1630 the ratio of violins to violas was approximately 3:1.

- After the plague, viola production declined precipitously and the ratio became closer to 25:1.

- Anecdotally we know this to be true: the Amati family and the early Brescian luthiers made a higher concentration of violas than later makers did.

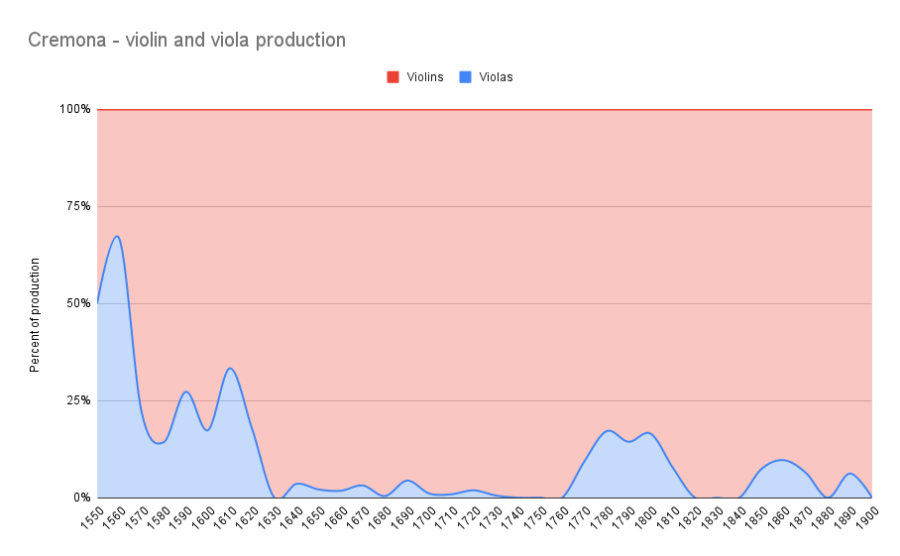

Here is another graph showing the stacked percentages of total production, but this time I have included only violins and violas made in Cremona.

-

- Between 1650 and 1700, violas represented only 2-3% of instruments made in Cremona (cellos are excluded from this graph).

- Nicolo Amati continued to make a few excellent violas but Stradivari’s violas account for 1% of his production; the Guarneri family was similar; and violas by Carlo Bergonzi and the Rugeri are almost non-existent.

- By 1740 there were virtually no violas being made in Cremona.

- And then around 1770 we see an increase in viola production when makers like Storioni and Nicola Bergonzi began making violas once again.

Regional production of violas compared to violins

These five graphs show the production of violas and violins in five principle violin making cities of Italy: Cremona, Brescia, Milan, Venice and Naples. The scale and time frame changes slightly to accentuate the trends of each city. Some things I notice:

-

- Each city shows booms and busts. Generally speaking, the first part of the 18th century was a boom and somewhere towards the middle of that century came a bust.

- Naples seems to have kept the boomtime running longest; it wasn’t until the late 18th century that Naples began to decline.

- Brescia blooms only briefly when the Rogeris came to town.

- Milan, Venice and Naples show a clear resurgence of the ‘Modern Italian’ school starting in the late 19th century and continuing until the 1920s or 30s.

- Viola production is fairly flat in all of these graphs. We’ll have a look at the details to see why.

Viola making in other European cities

This next series of graphs breaks down the production of violins, violas and cellos in the major violin making cities of Europe. Some observations:

-

- Brescia had the highest percentage of violas but Florence and Milan weren’t far behind.

- Cremona and Naples made the lowest percentage of violas.

- London is by far the most cello-intensive city, followed by Rome and then Venice.

- Almost no violas were made in Mantua in the 17th and 18th centuries.

- The final graph shows instrument production in Cremona and Brescia from 1550-1680. Brescia was a viola town.

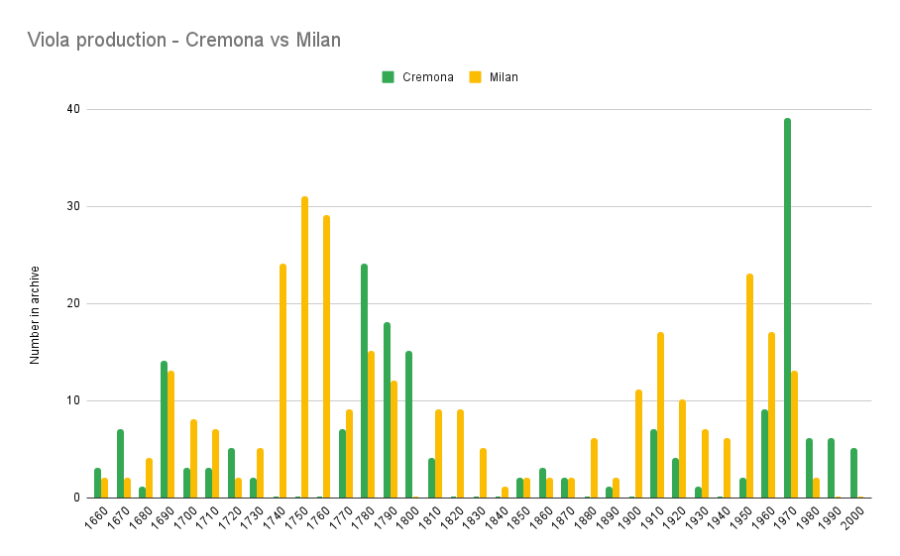

The Milanese viola

Milan has always been favored for violas and I was curious if data could help explain why.

As we saw in the previous charts, the percentage of violas made in Milan is not substantially different from other cities and yet Milanese violas are almost universally highly regarded by violists and collectors. In my opinion there are two reasons why Milanese violas are so highly rated: The most significant reason is that Milanese violas are almost invariably of a good, contralto size that’s optimal for modern viola playing. And secondly, Milanese makers made lots of violas in the middle of the 18th century at a time when the rest of Italy wasn’t making many violas at all. The graph above shows the production of Milan (in yellow) versus that of Cremona (in green). When Cremonese viola making all but stopped in around 1740, Milanese makers redoubled their efforts and their production increased. Consequently, the violas made by Grancino, Testore, Landolfi, Mantegazzi and Rivolta are in relative abundance, are all the right size and have benefited from nearly three centuries of being desired by violists.

When Cremonese viola making all but stopped in around 1740, Milanese makers redoubled their efforts and their production increased.

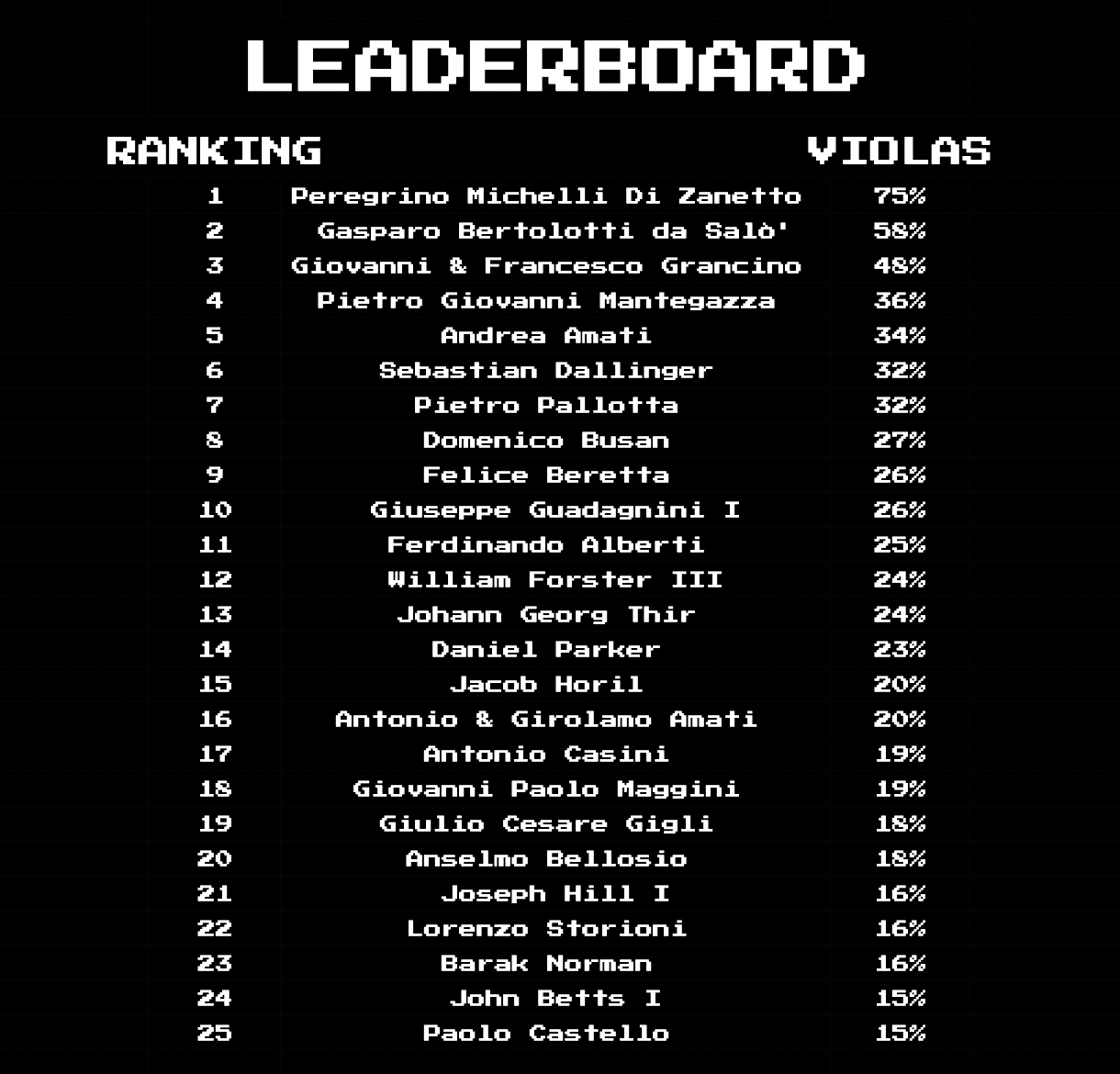

Who made the most violas?

Excuse the corny graphic. These are the top 18th century viola makers ranked by their percentage output.

-

- 75% of Zanetto’s instruments were violas.

- 58% of da Salò’s instruments were violas.

- The average for 18th century makers was around 7%. This means that for every 15 instruments, one was a viola.

- Only 1% of Stradivari’s instruments were violas.

- The Testore family averaged 7%.

- The Landolfi family was similar.

- The Mantegazzas, however, made 36% and Rivolta made 43% (he’s not included above as he was predominantly a 19th century maker).

- (I excluded makers with fewer than 20 instruments in the archive to get this data.)

- The award for the highest percentage of violas ever made goes to the 20th century Canadian-American maker Otto Erdesz whose production was 86% devoted to violas.

- Some makers avoided violas altogether, most notably Guarneri ‘del Gesù’.

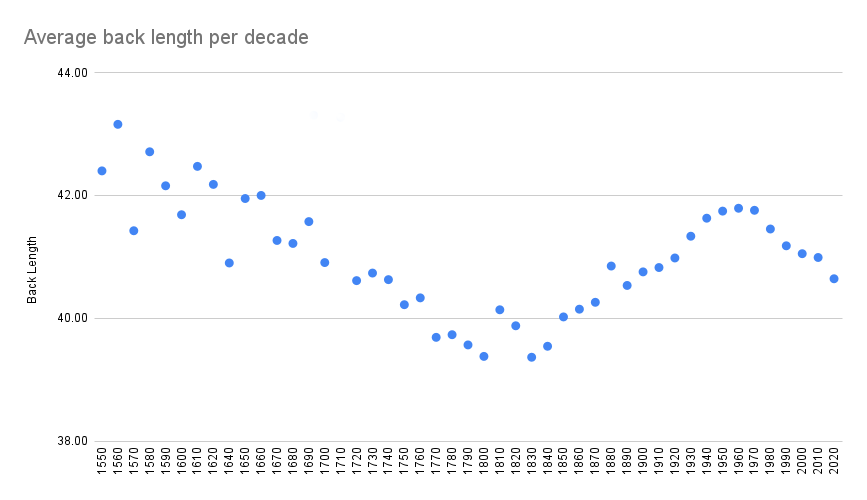

Size matters but preferences change

Violas come in all shapes and sizes. They can be 37 cm or 43 cm or anything in between. I wanted to see if I could represent these dimensional trends graphically and see what that might reveal.

This graph shows the average back lengths for violas made in each decade between 1550 and 2020.

-

- The tenore violas of the 16th and 17th centuries were large, often over 43 or 44 cm.

- By the late 18th century, smaller violas were more popular in most regions.

- Even though many makers, such as Storioni, Pressenda and Vuillaume, made both a smaller model and a larger model between 1780-1860 , the average size was still smaller than 40 cm.

- In the early 20th century, the contralto viola with a back length of around 41 cm emerged as the favorite but variations persisted.

- There is one glaring inaccuracy with the data behind this graph: many violas from the 16th and 17th centuries have been substantially reduced from their original dimensions. This chart reflects the reduced dimensions. With that in mind, the actual trend-line would be even more dramatic.

Finally, as an anecdote to excessive charts and numbers, I leave us with photographs of one of my favorite instruments of all time, the 1697 ‘Primrose, Lord Harrington’ Guarneri viola which Tarisio sold in 2012. The Guarneri family didn’t make many violas – there are fewer than 10 that survive – but they got it right… This viola, made just before the turn of the 18th century is 41.3 cm long and its model, to many musicians and luthiers alike, is pretty close to perfect…

![]()