The ‘Sleeping Beauty’ of c. 1704 dates from Stradivari’s golden period. But what makes this instrument stand out even among its immediate contemporaries is its fairytale history, which I was able to trace back thanks to the help of Dr Wolfhard von Boeselager, whose family owned the violin for almost 300 years.

The violin has an apparently original label with a date of either 1720 or 1729 – the last handwritten digit is unclear. Given the label indicates a production year in the 1720s, why is the violin thought to have been made in 1704? One reason lies in its quality. Its perfectly cut f-holes, majestic scroll and precise purfling are all typical of the golden period. But it is particularly the wood and its startling resemblance to the ‘Betts’ of 1704 that has convinced experts – among them the Hills – that the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ must have been made in the same year. The Hills suggested that the later date was because ‘[the violin] might have remained in Stradivari’s possession, and only had the label put in it when he sold it. This to our minds is the only explanation of the difference between the date and the actual style of the work.’ (Hill certificate dated March 1, 1897)

Who bought the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ in Cremona, how did it get to Germany and why did it subsequently become forgotten? The violin’s early history is unclear, but the buyer could have been Baron Franz Wolfgang von Boeselager zu Nehlen, who was traveling in Italy around the year 1724. It was also the baron who acquired the famous Höllinghofen Castle in west Germany in 1754, primarily for use during the hunting season. It is in the castle, assuming this theory is correct, that he must have kept the violin, given its later history.

An alternative hypothesis regarding the violin concerns the family of Adolfine von Boeselager, who was the wife of Carl von Boeselager, the great-great-grandson of Franz Wolfgang. Adolfine came from the Haxthausen family and a diary of a later family member states that the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ actually belonged to one of her uncles (one of seven Haxthausen brothers). The Haxthausen were determined opponents of Napoleon and the brothers were forced to flee Germany in 1810, when the troops of the French general occupied this part of Germany. It is possible that Höllinghofen Castle provided a temporary hideout for them – and the need to leave the country in a hurry would explain why the violin was left behind.

Portrait from around 1850 of Carl von Boeselager (center holding a musket) with his wife Adolfine (seated) and their children and grandchildren. Next to Carl on the left is his eldest son, Carl Maximilian, ‘Max’. Heessen Castle is depicted in the background

Whatever the reason for its abandonment, like the princess in the fairy tale, the violin then fell into an undisturbed sleep in Höllinghofen Castle. Meanwhile, Adolfine and her family were living at Castle Heessen, roughly 40 kilometres away. In 1854 a major fire damaged Höllinghofen considerably. Adolfine’s son, Carl Maximilian von Boeselager (1827–1899), known as ‘Max’, had it repaired and partially rebuilt, and then moved in with his family, apparently unaware that the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ lay forgotten within its walls.

‘Max’ moved in to the castle with his family, apparently unaware that the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ lay forgotten within its walls

Left: Watercolour of Höllinghofen Castle with ‘Max’ von Boeselager and his family. Right: the castle as it looks today, viewed from the side

In the 1870s the von Boeselagers became embroiled in the ‘Kulturkampf’ (‘culture struggle’) between the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, and the Catholic Church, which caused the imprisonment of pastors and bishops, the confiscation of valuable church treasures and a breakdown in diplomatic relations with the Vatican. The von Boeselagers were Roman Catholics and Max supported the Catholic Church against the state. In 1881 he decided to leave Germany with his wife and five children, a provocative gesture that resulted in his banishment by the government.

The family went into exile in England, leaving Höllinghofen Castle uninhabited for several years. Then in 1886 two of Max’s sons, Karl Franz Max (1864–1900), called ‘Manus’, and Dietrich (1867–1920) spent a few days at the castle to hunt in the nearby forest. In the fireplace room of the castle the young men were looking for old empty rifle cases that lay on top of a shelf along with antique folios. Manus dropped his ring among the clutter and in the hunt for it the brothers noticed an aged violin case, which to their surprise contained a beautiful instrument. Shortly after this exciting discovery the violin was brought to the Hills in London, who confirmed that it was an original instrument by Antonio Stradivari. It was at this point that the Hills determined its construction year as 1704. Restored to playing condition and equipped with their certificate, the violin reawoke to new life.

Left: the Villa Baronata in Minusio, where Wilma (pictured with the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ in 1904) lived

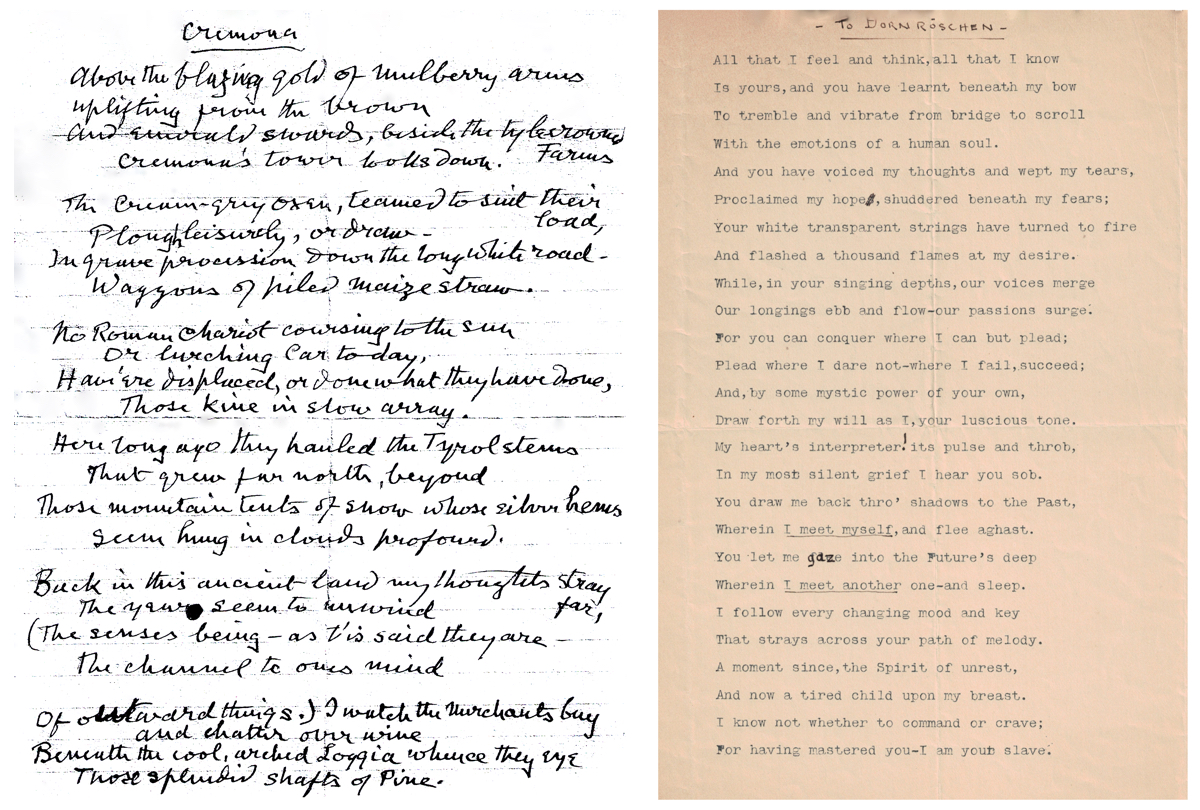

Max’s children were interested in music and played various instruments. In particular, his daughter Wilma (1871–1950), called ‘Muck’, played the violin excellently at the age of 15. Wilma fell in love with the violin and so her father determined in his will that she could keep the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ for her lifetime. She performed with the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ in public and private concerts, including at the Beethoven Weeks in Bonn, when she was accompanied by pianist Elly Ney. Wilma remained unmarried and lived initially with her brother Dietrich and his family at Heessen Castle; later on she moved to the Villa Baronata in Minusio, not far away from Locarno on Lake Maggiore. Her sister-in-law, Millicent von Boeselager (Manus’ wife), dedicated to ‘Wilma’s Strad’ two of her romantic poems entitled ‘Cremona’ and ‘Dornröschen’ (‘sleeping beauty’).

The two poems that Millicent von Boeselager dedicated to ‘Wilma’s violin’

After Wilma’s death the violin returned to the head of the family, Maximilian von Boeselager II (1911–1989). Since the Villa Baronata had been expropriated by the Swiss government after the Second World War, Maximilian II feared that the fate of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ would be similar. Therefore, through the help of a friend, the lawyer Dr Fritz Reinhardt, he stored the instrument in a bank vault, at first in Solothurn and later on in Zurich. Although the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ was yet again hidden away, Reinhardt made sure that the violin was checked by an expert twice per year and occasionally left the safe to be played.

In order to communicate secretly about the instrument, the two men gave the violin the nickname ‘Saint Bernard’

In order to communicate secretly about the condition of the instrument, the two men gave the violin the nickname ‘Saint Bernard’ (a breed of dog). Thus their correspondence between the years 1951 and 1990 often contains remarks concerning the health of the St Bernard and his deeds. Dr Reinhard wrote on April 6, 1951: ‘Our St. Bernhard is doing fine and is well taken care of. Nothing can happen to him. A first-class veterinary surgery, which employs the latest facilities, will take care of him for 70 francs per year.’ (The ‘vet’ was the violin maker Fritz Baumgartner of Basel.) There was also a dedicated group of ‘friends of Saint Bernard’, who lent the violin out for concerts. For example, in 1972 the instrument was played by Michel Schwalbé, concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, for performances with Karajan, and in 1992 Alejandro Mettler played it with the Zurich Symphony Orchestra. During this last period in Switzerland Maximilian II commissioned his son, Wolfhard von Boeselager, to take care of the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ while he studied philosophy in Fribourg and later on worked at the University Institute for Eastern Europe.

In 1985 Maximilian II gave the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ to his granddaughter, who showed musical talent. However, she decided to embark on a different career and sold the violin in 1995, bringing to an end its almost 300-year association with the Boeselager family. Since 1996 the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ belongs to the German credit institution L-Bank and is played by the soloist Isabelle Faust.

With thanks to Dr von Boeselager and his family for assistance with source materials.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an Italian art historian and has authored several books including the four-volume ‘Antonius Stradivarius’.

Isabelle Faust on the ‘Sleeping Beauty’

This is an almost magical instrument. I fell in love with it at first sight. That’s why I immediately started looking for a sponsor for it and was fortunate enough to find it in the L-Bank. That was in 1996. Since then I have been allowed to play the ‘Sleeping Beauty’, so we have been a couple for over 20 years. Before that I also had some Stradivari experience. The L-Bank owns a very early one that is built according to the Amati model (the ‘Tullaye’), a wonderful instrument for chamber music. I was allowed to play that for a while.

Isabelle Faust with the ‘Sleeping Beauty’. Photo: Felix Broede

In my opinion, the violin sounds very balanced and has a lot to offer. On good days, it is hard to surpass. Sometimes it can be difficult to handle, because its sound may not be completely full and open. It depends primarily on the climatic conditions and on the hall, of course. But it definitely has a very elegant, bright, floating sound. It responds very well to a light playing style and also likes gut strings and a deeper mood. So it is not an instrument that wants to be ‘pushed’.