Decorated quartets by the celebrated French violin maker Jean Baptiste Vuillaume are rare and of great historical importance. This fine viola, recently acquired from Tarisio by the Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation, was originally part of a quartet commissioned by the Russian aristocrat, composer, capitaine d’état and patron of the arts, Count Dmitri Nikolaevich Sheremetev.

During the 19th century the Russian Empire developed a longstanding, though tumultuous, relationship with France. The Age of Enlightenment had greatly inspired the reign of Catherine the Great and had provided the foundation for a strong intellectual and cultural exchange between France and Russia. Elements of French culture, such as music, literature and art, became embedded in courtly life in Russia. With the interest in western European music, naturally an interest in musical instruments followed.

By the mid-19th century there were a handful of significant Stradivari instruments in the hands of nobles in St. Petersburg and Moscow.

By the mid-19th century there were a handful of significant Stradivari instruments in the hands of nobles in St. Petersburg and Moscow. The French historian Jules Gallay, the English dealer David Laurie and the Italian collector Count Cozio all cataloged Italian instruments in Russia. But the aristocracy was also interested in new instruments. In 1845, the violin maker and dealer Georges Chanot traveled to Moscow and sold several instruments. Likewise, Tsar Nicholas I owned several instruments by Jean Baptiste Vuillaume.[1] and this naturally meant that his court had to follow suit and build their own collections of French instruments..[2]

The roots of the Russian noble Sheremetev family can be traced back to the days of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century. The Sheremetevs were one of the most powerful and influential families in Russia and held many high commanding ranks in the Russian military and governorships.

Count Nikolai Sheremetev, by Vladimir Borovikovsky, 1812

Count Dmitri Nikolaevich Sheremetev was born in 1803 to Count Nikolai Petrovich Sheremetev (1751-1809) and his wife Praskovya Ivanovna Kovaleva (1768-1803) in Saint Petersburg. Though his parents were from very different backgrounds, both were musically inclined.

Dmitri’s father, Count Nikolai, was then one of the richests landowners in Russia, with over 200,000 serfs, and was also a passionate music lover with extensive knowledge of the arts. He had received a European education and studied the cello in Paris; upon his return to Russia, he took over the management of his father’s theater.[3] and ran the Capella choir of serfs. He enjoyed conducting orchestral performances and while it was usual for aristocrats to have up to three performing bodies in their courts (typically a choir, a horn orchestra and a symphony orchestra), Sheremetev had a theater with both opera and ballet groups, a symphony orchestra, a brass orchestra, a horn orchestra and a choir.

Praskovya Ivanovna Zhemchugova-Sheremeteva, by Nikolai Argunov, 1803. The pendant of her necklace shows a miniature portrait of her husband Nikolai Sheremetev.

Praskovya Ivanovna Kovaleva was the daughter of a blacksmith, one of Sheremetev’s serfs. She was also a famous and talented actress and opera singer in the serf theater run by Nikolai and his father Pyotr. By age seventeen she knew how to read and write French and Italian, played the harp and clavichord and was widely considered one of the best opera singers of the 18th century..[4] Though their relationship was highly unorthodox and controversial in the eyes of 18th-century Russian society, Count Nikolai was deeply in love with Praskovya, who became his mistress for approximately fifteen years before being emancipated from serfdom in 1798. The pair were officially married in 1801, two years before the birth of their son Dmitri. Sadly, Praskovya passed away shortly thereafter owing to complications from tuberculosis coupled with the strain of her pregnancy.

Count Dmitri Nikolaevich Sheremetev, by Orest Kiprensky, 1824

Count Dmitry Nikolaevich Sheremetev (1803-1871) inherited and was a patron to his father’s theater, opera and the Capella choir. As a young man, he entered the regiment of The Horse Guards in 1823 and took part in the suppression of the Decembrist revolt in 1825. He was later promoted to Staff Captain (capitaine d’etat major) and as such took part in the Russian campaign against Poland; he was promoted to Captain in 1833. Finally, as per his wishes, he was dismissed from military service and transferred to the civil service in 1838, serving as a collegial adviser to the Ministry of the Interior, before being promoted to Chamberlain in 1856. He also continued his parents’ mission to help the sick, poor and orphaned. Dmitry was an administrator of the Moscow Hospices, making large donations to these causes, and his dedication to charitable work earned the respect of Saint Petersburg society and the imperial family.

In 1846 Dmitry Sheremetev became an honorary member of the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Society. Though his parents passed away when he was still quite young, it is perhaps no surprise that Dmitry Sheremetev was an avid music lover and connoisseur. For half a century, he maintained a choir chapel in his home on the Fontanka in Saint Petersburg and he took care of people in the arts, providing material support to artists, singers, and musicians. He died in 1871 at his estate in Kuskovo near Moscow and was buried in the family tomb at the Lazarevskaya Church in Saint Petersburg.

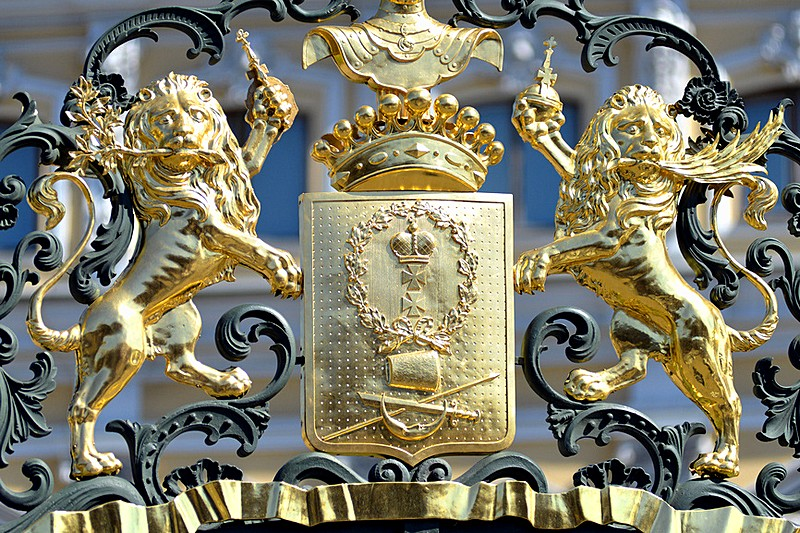

The gilt and painted Sheremetev coat of arms on the back of the Sheremetev viola: two lions hold a scepter and a cruciger with laurel and olive branches in their mouths; a central crown stands above two crosses encircled by a laurel wreath. The motto “Deus conservat omnia” translates to “God preserves all.”

The Sheremetev coat of arms, which decorates the backs of the instruments in the Sheremetev quartet, features two lions holding the imperial symbols of a scepter and a globus cruciger, with laurel and olive branches in their mouths. The Blazon has a crown at the center with two crosses below, circled by a laurel wreath. At its base there is a spear and sword as well as a traditional boyar hat, harking back to their heritage as boyars prior to the Romanov dynasty. The motto reads “Deus conservat omnia”, which translates to “God preserves all”, and the coat of arms can still be seen today on the entrance gate of the Sheremetev Palace in Saint Petersburg. Fittingy, the palace now serves as the State Museum of Theatre and Musical Art and houses a musical collection of 3,000 instruments.

The Sheremetev coat of arms can still be seen today on the entrance gate of the Sheremetev Palace in St Petersburg.

At the peak of the empire, the Sheremetevs were one of the richest noble families in Russia with palaces in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, extensive estates and hundreds of thousands of serfs. And then, in 1917, the revolution changed everything. Within a matter of months the Sheremetevs lost it all. Some of the family members were arrested and executed while others fled the country with nothing more than what they could carry.

We don’t know what happened to the Sheremetev quartet during the time of the revolution. Indeed, we don’t even know if it was still in Russia when the revolution began. But by 1929 the quartet had arrived in America, in Chicago specifically, and was in the possession of the prodigal cellist and conductor Alfred Wallenstein.

In 1917, the revolution changed everything. Within a matter of months the Sheremetevs lost it all. Some of the family members were arrested and executed while others fled the country with nothing more than what they could carry.

The child of Austrian immigrants, Wallenstein made his early career on Broadway playing in the pit orchestras of silent films. At age seventeen he joined the cello section of the San Francisco Symphony. By 1919, when he was just twenty, Wallenstein was playing with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He traveled to Leipzig to study with Julius Klengel and then returned to the job of principal cello of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In 1929 Wallenstein was appointed principal cellist of Toscanini’s New York Philharmonic.

It’s unclear how or when Wallenstein acquired the quartet, but in 1929 he presented it to the Chicago branch of the Rudolph Wurlitzer company in part exchange towards the purchase of the 1721 Montagnana cello [42865] that had been played by Andrè Hekking for 25 years and most recently owned by the department store magnate, Rodman Wannamaker..[5] The price that Wurlitzers asked for the cello was $16,200; they allowed a trade-in value of $3,500 for the Vuillaume quartet..[6] At the time, a certificate from Les fils de J. Tournier accompanied the quartet.[7], possibly indicating that the quartet was acquired at the shop of Henry Tournier who was active in Paris between 1914 and 1925.

The Sheremetev quartet as photographed by Wurlitzers in the early 20th century.

Wurlitzer sold the quartet to Francis C. Dale, an attorney from Cold Spring, NY, in November of 1929 less than a month after the cataclysmic stock market crash of 1929..[8] In addition to this quartet, Dale owned a 1722 Stradivari and the c. 1741 ’Hart, Kreisler’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’.[9]

Four years later, the quartet came back to Wurlitzer on consignment. In 1934 Wurltizer sold it to Norman L. Goss, a “music lover of Southern California”[10]. At some point around the middle of the 20th century, the quartet was in the hands of the San Francisco dealer Ignazio “Nash” Mondragon and soon was disbanded. According to Ernest Doring writing in Violins & Violinists, the cello went into the possession of J. A. Fabro and one of the violins went to H. R. Lange.[11]

Sometime around 1973 the Sheremetev viola and one of the violins were sold through William Moenning & Son to Albert Kaplan a distinguished psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. Kaplan was passionate about fine instruments and was a founding member of the Violin Society of America. In 1977 the Sheremetev violin and viola were offered at an auction at Tepper Galleries in New York.[12]

Since 1994 the Sheremetev viola has been owned and played by French violist Pierre Lénert, first solo violist of the Orchestre de l’Opéra National de Paris. It is on this instrument that Pierre Lenert recorded the 24 Caprices by Niccolo Paganini for the Paraty label in 2017.

Earlier this year, Tarisio facilitated the sale of this viola to the Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation.

Notes:

1. Sylvette Milliot, Jean Baptiste Vuillaume et sa famille, 2006, p.191.

2. Ibid.

3. Marina Ritzarev, Eighteenth-Century Russian Music, 2016, p. 256-259.

4. Douglas Smith. The Pearl: A True Tale of Forbidden Love in Catherine the Great’s Russia. New Haven CT, Yale University Press, 2008, p. 3.

5. Private archives.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Cozio

10. Harvey S. Whistler, “Jean Baptiste Vuillaume And His Master Workmen,” Violins & Violinists, January, 1948, p. 8

11. Ernst N. Doring, “Tabulation Of Instruments By Jean Baptiste Vuillaume,” Violins & Violinists, November-December, 1958, p. 261

12. Philip J. Kass, “An American First: Musical Instrument Auctions At The 84 Tepper Galleries And The Sotheby Parke Bernet,” Journal of the Violin Society of America, vol. II, no. 4, 1976, p. 84.