Santo Serafin arrived in Venice in 1721 and quickly became one of the city’s greatest violin makers, his instruments featuring consistently high-quality materials and refined workmanship. Tarisio’s London auction this month includes two examples of his mature work – a violin from c. 1743 and a cello dated 1740.

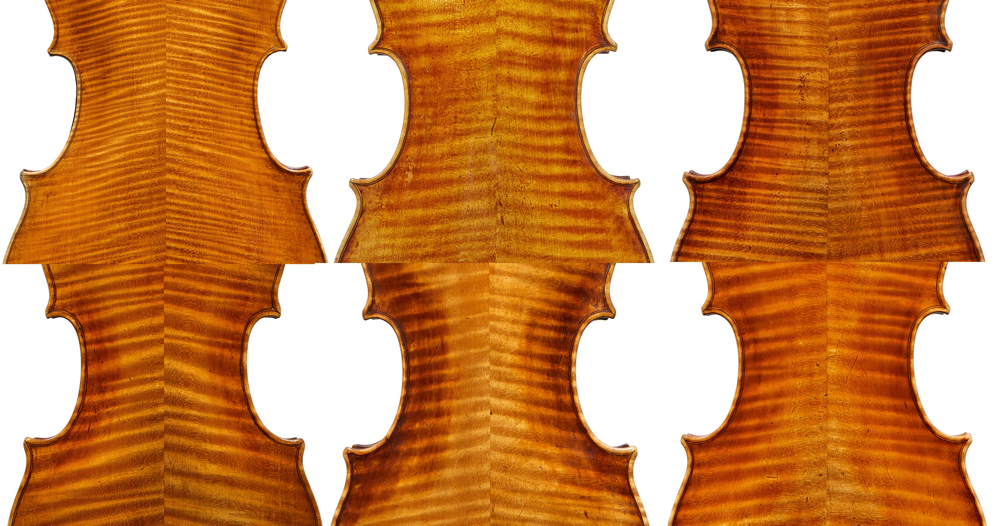

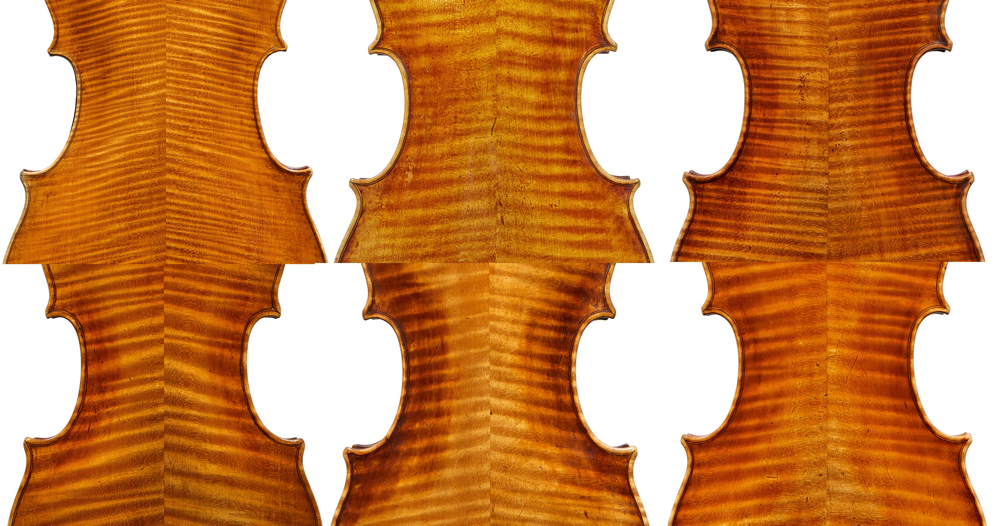

Examples of the highly figured maple often used by Serafin

Serafin’s wood selection is consistently among the most extravagant of all 18th-century makers. His backs are almost always in two pieces of stunningly flamed quarter-sawn maple and occasionally he used maple with bird’s-eye figurations.

Serafin’s wood selection is consistently among the most extravagant of all 18th-century makers

The elaborate iconography of Serafin’s ornate label might reference a seraph

The label that Serafin used is one of the most ornate and decorated in the history of Italian violin making. Unlike most 18th-century labels, which were set, at least in part, from movable typeset letters, Serafin’s labels were printed from an engraved plate. The words ‘Sanctus Seraphin Utinensis Fecit Venetiis Ann. 17__’ are set in a banner of icons: a pair of wings joined by a scalloped shell form the upper edge; a pair of paper scrolls forms the border to the left; and an upside down violin with c-shaped sound-holes and a bow form the right side. The lower border is composed of two tendrils whose curling points make up two eyes above a nose with whiskers or wings fanning outward. Possibly the iconography of wings references a seraph, which in the Christian tradition was an angel of the highest order and had six wings.

Most Serafin instruments bear the maker’s name to the lower rib. Unlike a traditional brand, Serafin’s name appears as light letters set against a dark background. The letter spacing and alignment varies from one instrument to the next which has led to the theory that what we perceive as a brand is actually his name carved in shallow relief with the background filled with black mastic.

Curiously these two instruments no longer have the maker’s mark to the lower rib. On the cello it has been replaced by an inset strip of maple; on the violin, the left side is barely visible but the rest has disappeared. The lower rib of both instruments is still in one piece and uncut. The maker’s mark illustrated is from the ‘Baron Knoop’ Serafin of c. 1743, which Tarisio recently sold by private sale.

The edges of the c. 1743 violin are a generous 4.7 mm on the back and 3.3 mm on the front. Unlike most classical Italian instruments, the edge height dips at the corners instead of flaring. The back corners dip to 4.0 mm and the top corners to 3.0 mm. At the button the edge swells to a generous 5.1 mm.

The central strip of Serafin’s purfling has a creamy smooth appearance and the black strips are thin and fine. At the corners the purfling mitres point towards the centre of the corner rather than being biased towards the C-bouts.

One of the distinctive features of Serafin’s instruments is the semi-circular notch at the upper end of the pegbox. Often called the ‘chapelle’, this feature is also seen in 18th-century French instruments, where different patterns were used, possibly to identify the maker of the head, which was not necessarily the maker of the instrument’s body. In Serafin instruments the notch is formed by a gouge and not a drill, which wouldn’t clear the overstand of the volute. The semi-cylindrical cut extends to the base of the pegbox floor. At the upper edge, the straight sections of the pegbox wall are finished with a neat chamfer.

The interior walls of the pegbox are significantly undercut at the base to produce interior walls which are convex:

Serafin violin pegbox wall

Serafin violin and cello pegboxes

The pegbox tapers evenly on both the violin and the cello. There are no visible scribe-lines and few compass-points. The chin is not a section of a circle but slightly oval.

Serafin violin undervolute

Under the volute the centerline dissolves and the two halves merge into one unified curve. We see the same treatment on Amati instruments. The varnish is thick and coagulated where it is less disturbed under the volute. On the violin we see the impression of a thumbprint, most likely not the maker’s, but perhaps that of an idle musician on a warm evening.

The pegbox walls are flat into the first turn. The carving becomes deeper through the second turn and terminates in a sharply cut eye. Toolmarks are visible throughout.

The blocks and linings are in spruce. The linings are tall (18mm on the cello) and the blocks are wide. In both instruments the centre lining is let into the blocks but on the violin the profile of the lining was cut before it was glued into the block, whereas on the cello the profile was cut later.

Serafin’s varnish ranges from a clear golden orange to a dark reddish brown. Under UV light the delicate texture of the varnish appears like chocolate and caramel:

The violin and cello under UV light

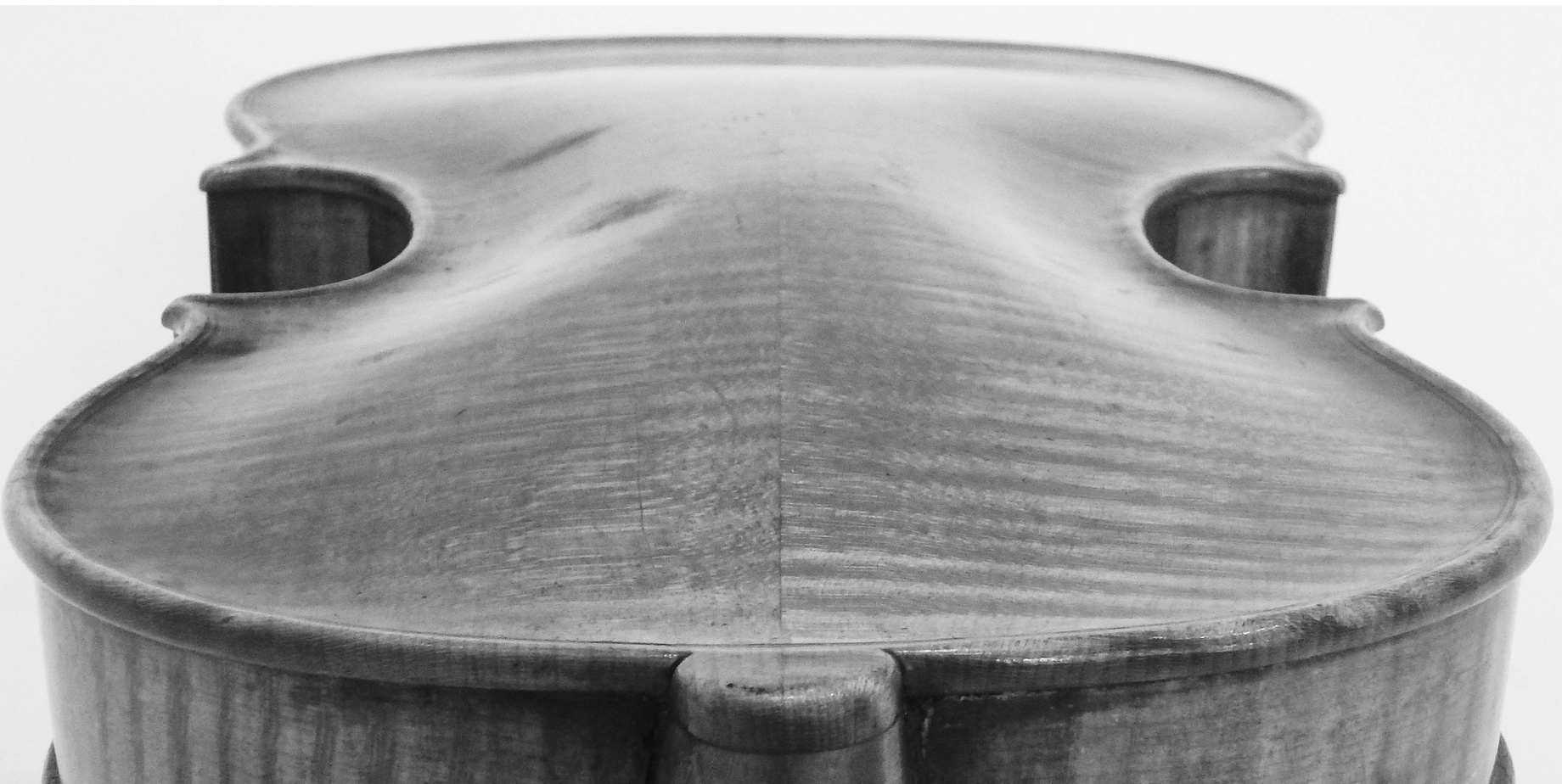

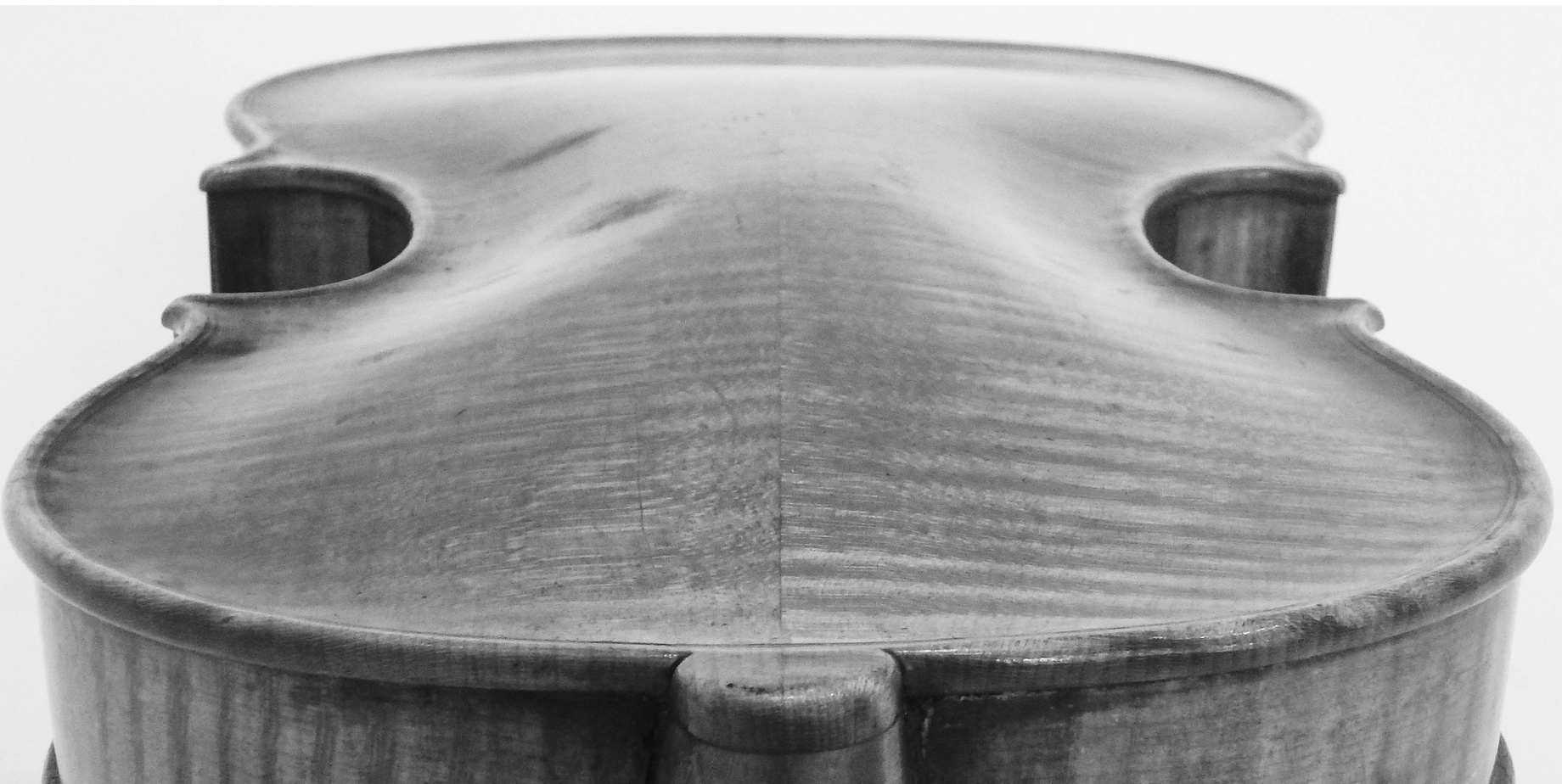

The gentle arching of the c. 1743 Serafin violin

The Serafin cello is Lot 45 and the violin is Lot 189 in Tarisio’s October London auction. Read more about the cello in our earlier feature on Serafin’s life and work, by Stefan Hersh.