Paul Martin Siefried passed away on November 28, 2019. While Paul was an excellent bowmaker, it was his work as a restorer which was particularly well regarded, even legendary. His creative mind and powerful observation skills developed techniques which made him the premier US restorer for over four decades. His reputation was such that in the early 1990s Bernard Millant asked him to lecture in Paris on his restoration techniques.

Paul was artistic from an early age. He found himself in San Francisco at the height of the hippie days, selling leather goods which he had hand-crafted out of his VW minibus. His leather work brought him to the attention of Bay Area violin shop owner Nash Mondragon, who took him on, initially doing menial jobs but he quickly worked his way up. Paul soon moved to the premier West Coast shop of Hans Weisshaar in LA. Paul used the shop’s extensive bow collection and Weisshaar’s insightful critiques to teach himself how to make bows. He won three gold medals in each of the two Violin Society of America competitions he entered (1978, 1980), as well as third prize in the 1991 Etienne Vatelot competition in Paris.

Many people have described Paul as intensely competitive. He once said he was quite disappointed when he was asked to judge the 1982 VSA competition rather than be allowed to compete a third time. One of the judges had fallen ill and Paul was asked to take his place. Paul’s goal was to win a gold medal in every bowmaking category in a single competition, as in the previous competitions he had “only” won gold in three out of four categories (and this was despite one time finishing his competition bows after having broken both his wrists in a car accident).

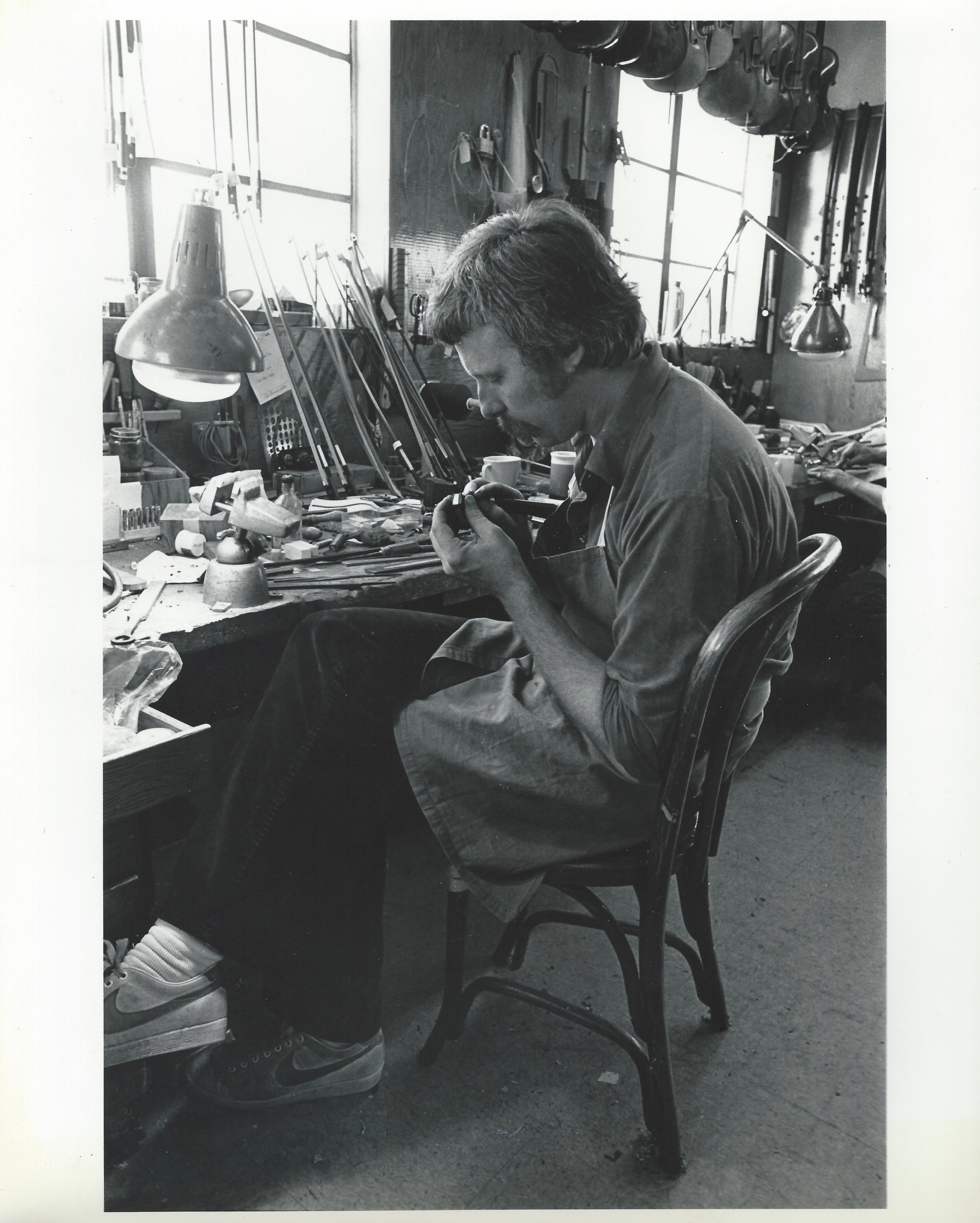

Paul’s style shows a definite influence of makers from the first half of the 19th century; the dimensions of the Parisian eye show a Tourte influence creeped in. “Most makers think the ring on the Tourte Parisian eye is 1.0 mm,” he once told me. “You might measure it 1.0, but if you make it 1.0 it looks wrong, it looks too big. But if it’s 0.9 it works perfect.” Photo credit: Steve Eddy Violins

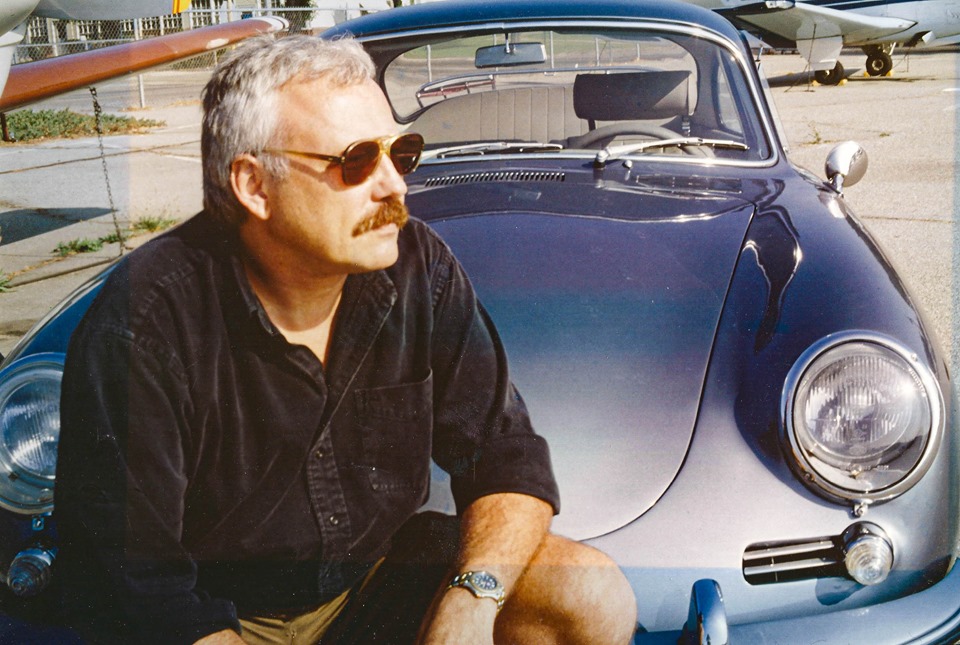

Paul was one of those people who worked at a high level no matter what he did, restoring a Victorian house in Port Townsend, WA, or before that restoring his father’s bathtub Porsche, the car in which he learned to drive, or building his own sailboat or kayak. When working in Port Townsend he worked six days a week from 8 to noon, took an hour off to feed himself and his voracious reading habit, then like clockwork continued from 1 to 5. At 5 he would dive into whatever non-bow projects he was at work on (and he always had at least one going), often seen running to the hardware store in his vintage VW bus or mid 50s pickup.

He never seemed to be rushing his work, always had time to chat or show a visiting colleague or debutante one of the many the Tourtes or Persoits or Simons that were on his bench at any given moment, but he was incredibly efficient. “He was completely relaxed when he worked,” says his friend and colleague, luthier Joe Grubagh. Luthier Sigrun Seifert adds, “At Weisshaar’s no one was allowed to lean back on their chair, but Hans [Weisshaar] let him lean back.”

Paul at Weisshaar’s, being allowed to lean back.

Despite his competitive nature, Paul was always remarkably open with his methods, sharing them with anyone who would ask, occasionally lecturing, and often judging competitions. Anyone wanting to copy an older frog and button HAS to reference a lecture on copying a historical frog that he gave to the VSA in 2002.¹ Luthier John Waddle remembers that when he worked at Weisshaar’s there were times when over a lunch period (the shop closed for an hour, no matter who knocked at the locked door) Paul would take a classic bow from the collection and discuss its finer points with whoever wanted to participate, often several people.

His enthusiasm didn’t start and end with bows, however. His appreciation of the work came from a deep-seated sense of aesthetics and form. “Whatever he touched, if he made something, it looked good,” says Los Angeles luthier J. Michael G. Fischer, who worked with Paul at Weisshaar’s and later located his shop across the alley from Paul’s bow shop in the Silver Lake region of LA. Fischer recalled the beauty of the stained glass windows Paul made for his Silver Lake shop. Paul himself once said, “If you have good hands and a good eye you can make almost anything.” Well, at least, he could!

Paul drew inspiration from many areas. Bowmaker and restorer Ole Kanestrom, who shared shop space with Paul for 7 years, says, ‘I would see it all the time – a repair might wait for a couple weeks while he perfectly imagined a new technique for how to best do the repair,’ often stating the method had come to him in a dream. For his personal bows, his inspiration was largely from Peccatte and especially Maire (German maker Klaus Grünke, who worked alongside Paul at Weisshaar’s and lived almost next door to him for a time, says Paul named his son after Maire). Fischer said “I always felt his bows were connected to older stuff, and not everyone was doing that.” This appreciation for the “older stuff” would have particularly been expressed in direct copies Paul made of classic bows. He was known to have made copies that were good enough to have fooled experts, some of which no doubt have been sold as originals (although no one I’ve ever talked to thought Paul himself would have sold them as anything other than a bow made by him). Grünke says copies they made at Weisshaar’s, often in collaboration, were never sold as originals, though, ‘now we realize the danger’ of having made them.

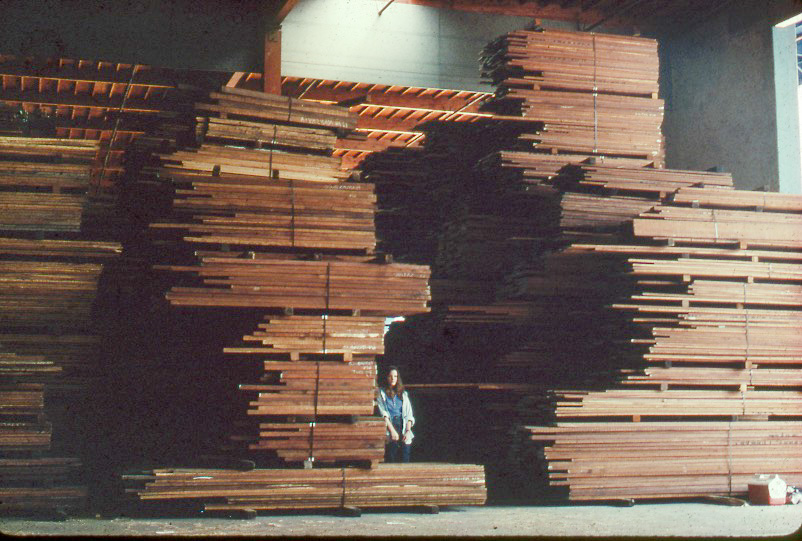

Only part of the pernambuco cache. Bowmaker Peg Baumgartel stands amidst the wood to give an idea of size.

Paul left the Weisshaar shop around 1983 to set up the Silver Lake shop. It was on the upper floor of a small storefront building, and many of LA’s orchestral and studio musicians would seek him out for repairs, restorations and sales. A few years later, a huge cache of Pernambuco, by one account over 200 tons, was found at a Los Angeles lumber yard. Although Paul wasn’t on particularly good terms with Hans Weisshaar at the time (he was, after all, a former employee who had left to open a competing shop), he approached Weisshaar and the two struck a deal over a handshake for Weisshaar to finance the purchase of the wood. Paul would pay the money back not only in dollars but by supplying a quantity of bows every year for many years. Paul and employees processed the wood for sale, a large quantity going to Japan, and much was sold to other bowmakers who would fly in (many from Europe) to choose from the large supply available.

The profits from this sale enabled him to move to Port Townsend, Washington, in the early 1990’s. For some time he had been searching for the perfect small town in which to settle, ideally to concentrate on building bows and leave the repairs and restorations behind. Port Townsend isn’t all that easy to get to, it’s three hours away from Seattle, often involving taking at least one ferry. However, musicians would continue to seek him out and with the rise of overnight shipping restoration dominated his work life until he was unable to continue working a couple years ago.

In Port Townsend Paul worked for many years in a building at the rear of the property of the 1874 Victorian home he restored. Because the front of the house faces east over a bluff, overlooking Port Townsend Bay, visitors would enter the property from the rear and immediately come upon the shop space to their right. The shop was the former pool house for the property, and in winter was heated by a central fireplace. In summer most of the doors were open, giving a natural, idyllic workspace. The space had large gardens and beautiful shade. Paul would love to take a break to go into the garden and pick weeds.

In 2007 he moved his work space to a small building in a nearby commercial district which he shared with bowmaker Ole Kanestrom, where any number of visitors would look through the many paned windows at a man practicing what must have seemed like an arcane, ancient craft.

Yes. You can make a living doing this. Or at least he could.

Paul with his “double bass” bow.

He had a good sense of whimsy and playfulness. He once made a bass bow with two heads and two frogs, oriented 180 degrees from each other, which was his “double bass” bow. For many years he had been trying to imagine how to make a frog in the form of a fishing reel, where one would tighten the hair using a mechanism similar to reeling in a fish. He was aware of and confident of his talents and status within the trade, yet was one of the least arrogant people one could meet. He had a deep-seated disgust of pretension, particularly from colleagues. While he had strong opinions he was always open to listening to the other side of a debate and was not afraid to change his mind. He was incredibly well-informed and articulate on numerous subjects, and always up for learning more.

Paul was the rare conversationalist who had a deep store of knowledge but didn’t feel the need to prove it; he rarely interrupted and yet was always able to move the subject further along, often with great humor. He was very generous with his friends, some of whom might come home from vacation to find a pair of Adirondack chairs made from Port Orford cedar mysteriously sitting in their yard. (Port Orford cedar grows in a limited habitat in Oregon and is prized among boat builders for boat planking. However, the wood has become prohibitively expensive for most boat builders. At some point Paul heard about a railroad bridge made of this wood that was to be salvaged, so he and a partner purchased the bridge and milled it into wood suitable for boat building. Then he made a sailboat from it.)

Many people remember Paul’s affable ways with clients. Michael Fischer says ‘he really knew how to work with people,’ and Grubaugh agrees: ‘He was a good colleague to have, and inspired others to do good work.’ Paul himself once said: ‘I never think of musicians as potential clients, I always see them as potential friends. I think they sense that.’ For many of his friends and colleagues, Paul’s legacy was to inspire us by being open, curious, generous and willing to tackle a new challenge. As for musicians, his lifelong friend (it was she who introduced him to Nash Mondragon to get his first job in the trade) violinist Ellen Pesavento’s take is, ‘He left a lot of string players very happy.’

¹VSA Journal Vol XIX, No. 1

View the December T2 sale