Last week, bow makers in France and around the world lost a father figure. Bernard Millant, who passed away on April 5, 2017, was a bow maker whose contagious enthusiasm touched us all and whose certificates of authenticity were the backbone of authority in this profession for the last 50 years.

Bernard Millant was born on May 13, 1929 at a time of financial, political and military upheaval. He was the son of Max Millant and the nephew of Roger Millant – makers, dealers and authors of the famous book on the life of Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume. At the end of the Second World War, business remained particularly arduous for the artistic professions. Few people embarked upon a career in the musical sector and violin making workshops were compelled to reduce their workforce. Millant often reminded me that he had been advised not to ‘enter the trade’, but passion prevailed.

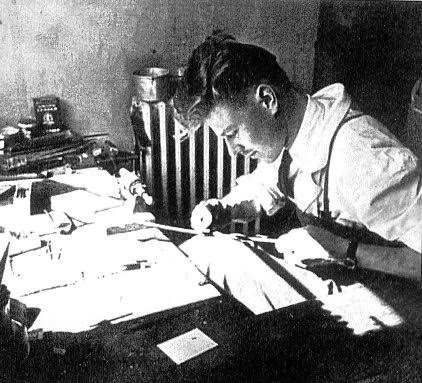

The workshop of Louis Morizot frères taken in 1948. Bernard Millant is in the front row on the left.

In 1946 Millant started a traditional apprenticeship in Mirecourt, in the workshop of Amédée Dieudonné. Two years later, on the advice of his father, he took up an additional apprenticeship in the workshop of Louis Morizot frères. This second phase in his training would prove decisive. At the age of just 21, Millant set up his workshop at 56 rue de Rome in Paris and it was at this address that he worked as both a violin and a bow maker for most of his life.

Millant is remembered by his clients as a wonderfully welcoming person. Every encounter was a testament to his boundless energy, his enthusiasm and his passion for his work.

I will always remember an anecdote dating back to a Luthiers et Archetiers d’Art de France convention in 1986, on the occasion of a reception in my workshop. Aperitif had just been served when I felt Bernard Millant’s hand pulling me backwards and him asking, ‘but Pierre, where are the bows?’ Millant was always eager to discover new bows; making new discoveries made him a happy man. That evening, none of us had much of the aperitif! All of our time was spent studying passionately, commenting and exchanging views on all the bows in the workshop. Each bow was viewed in its historical context. Sticks, frogs and buttons were examined separately; their specificities were brought to light as much as the general influence of the school to which they belonged. What a lesson it was for me, a young bow maker at the age of 23!

The historical contextualization of each bow and the formal analysis of each distinctive part is time consuming but brings invaluable information. Such a methodology is the foundation of expertise and forms the basis for the wonderful reference book L’Archet, written in 2000 by Bernard Millant and Jean-François Raffin.

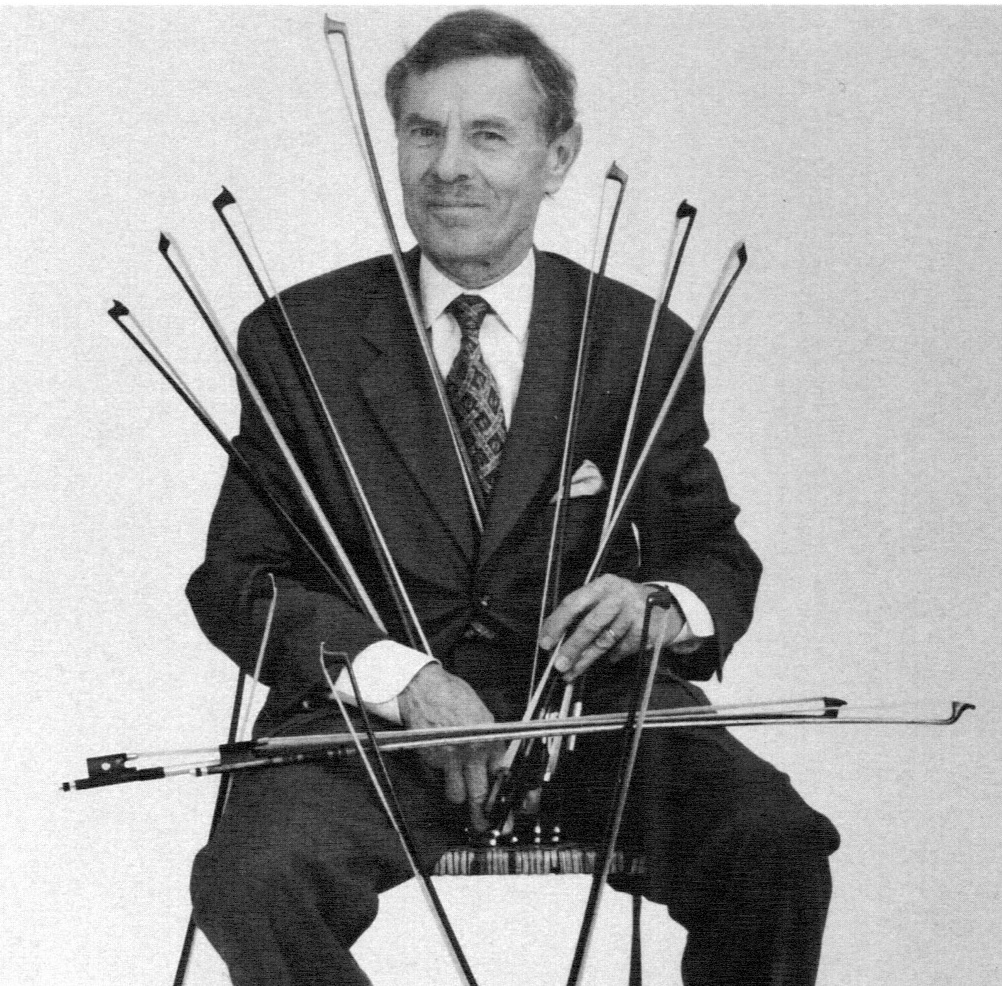

The convention of the Entente Internationale des Maîtres Luthiers et Archetiers d’Art in 2000. Mstislav Rostropovich was invited to the convention. This association of master violin makers today counts 163 members from countries across the world.

The French language is both beautiful and complex, and Bernard Millant’s writing was imbued with charm, subtlety and perfectly measured nuances. A native French speaker will appreciate the unique and inimitable style he used in his certificates. I have many anecdotes illustrating the vast extent of Millant’s culture, which I valued greatly. When working on his book, he paid me a visit in Brussels to take pictures of various bows as well as the old catalogs I have collected from the workshops of Bazin, Ouchard and others. During our conversation I pointed out to him that the golden period of François-Xavier Tourte coincided with the glorious years of Napoleon Bonaparte. The last battle fought by Napoleon in 1815 took place only 10 kilometers away from my workshop! The mere historical allusion was enough for Millant to launch into a famous poem by Victor Hugo. He recited it all by memory, not missing a single line, ‘Waterloo, Waterloo, morne plaine!’ (‘Waterloo, Waterloo, dismal plain!’).

Millant enjoyed sharing. Always open to constructive feedback and to dialogue, he would talk very humbly about his work. The bows he made are reflective of bows produced in France during the 1950–70s. They fall within the style of the Morizot school, but with particular care in the choice of materials, the shaping of the head and the mounting of the frog on the stick. The heads, solid and square, outline a simple and harmonious profile. His usual model is clearly inspired by the Peccatte brothers. The Hill-style underslide was much in fashion on the bows of the famous London house. Emile Auguste Ouchard, Louis Morizot frères and Marcel Lapierre also adopted this complex but functional adjustment system on some of their best bows.

The bow illustrated below is mounted in gold and tortoiseshell and has an inlaid fleur de lys motif. It was made for one of the great Parisian collectors of bows, Monsieur Jean Trible, and was completed in 1967, as stamped on the lower facet of the stick next to the mortise.

Millant’s passion for bows never faded; on the contrary, it remained intense until the end. A young violin maker recently told me about his first encounter with Millant last November, ‘I feel very lucky to have met him, he was incredibly generous in sharing anecdotes and history. In less than an hour, he gave me so much!’

Bernard Millant was a conscientious and honest craftsman, a fraternal and good-hearted colleague. He was blessed to be internationally acknowledged at the height of his art.