Charles Frederick Leggatt (1880–1917) was one of millions whose lives were cut short by the First World War. On April 26, 1916, aged 35, he was finally called up for military service, despite being a married man with a child to support. Recruitment for the war effort had previously relied on voluntary enlistment. Conscription, started in January 1916, was at first restricted to unmarried men but quickly included husbands and fathers as more and more conscripts were needed for the Western Front.

This bow shows the immaculate finish insisted upon by the Hill workshop (photos: John Milnes)

The two-colour lapping and white pearl eye are both original to the bow

Leggatt was born in Iver, Buckinghamshire, 20 miles west of London. His father was a gardener who died before the age of 50 leaving his wife to bring up five children. The family were originally from Hanwell (closer to London) and his mother returned there as a widow, setting up house with her mother-in-law. At the age of 15 Leggatt (known as Charlie) was apprenticed to train as a bow maker with the violin making firm W.E. Hill & Sons, who had built a ‘fiddle factory’ in Hanwell. He showed promise and gradually became a skilled maker.

Leggatt’s talents were accurate working of wood and metal, so when war came the obvious route to war service would have been in skilled factory production on the home front. However he enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps and trained in the Kite Balloon Section at Farnborough before transferring in September 1916 to infantry soldiering with the 16th battalion Sherwood Foresters. He served 17 months in France before dying of wounds on November 5, 1917, probably at the battle of Paschendale. It was a famously bloody encounter in which both sides suffered heavy losses.

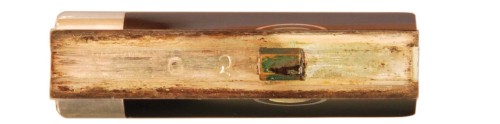

Leggatt’s mark was two parallel nicks on the face under the hair

Alfred Hill wrote of Leggatt in his diary: ‘a good bow-maker… only those who serve their apprenticeship and are properly trained, become proficient at our craft.’ His death was a serious loss to the Hill firm, particularly as another of their best bow makers, Sydney Yeoman, survived war service but with broken health. But the Hill shop regenerated and flourished for half a century more – a tribute to the skills of Alfred Hill and his chief assistant, William Retford, in finding and nurturing new talent.

The bow featured here serves as a memorial to Leggatt’s skills. Stamped W.E. Hill & Sons, it was made around the turn of the 19th–20th century when Retford’s influence was imposing itself on the Hill style. Samuel Allen, the first bow maker employed at Hills, had been a brilliant individualist but left no tradition. Retford, who took over leadership of the bow shop, set about devising a style of Hill bow inspired by Tourte and then imposed high standards of replication so that every bow that came out of the Hill shop bore their distinctive style. This bow is no exception and is highly typical of the Hill output of this period, including the immaculate finish that Retford insisted upon. Individual makers signed their work with a series of marks (and, later, numbers) on the face under the hair. Leggatt’s mark was two parallel nicks, as can be seen on this bow. Whereas Vuillaume in Paris half a century earlier allowed each of his bow makers an individual style, this uniformity was a salient characteristic of the Hill output.

The Hills marked the frog and stick with matching letters to ensure that each frog remained with the correct stick

John Milnes is a research assistant at Oxford University.

An exhibition celebrating The Hill Bow is due to be held July–October 2015 at the Bate Collection of historic instruments, Oxford.

The Bate has also set up an archive to collect material on the Hill bow makers, including photographs, letters, documents, tools and bows. If you have any material you would like to contribute, please contact John Milnes at milnes01@gmail.com.