This week’s carteggio presents an excerpt from the forthcoming publication TOURTE by Paul Childs and Duane Rosengard with additional text by Lucy Sante and Isaac Salchow. This important reference contains new research, beautifully detailed photographs of eighty Tourte bows and numerous previously unpublished documents. TOURTE is expected to be published in January 2022. Orders are accepted exclusively at Magic Bow Publications.

‘Cello bow by François Tourte, the ex-Norblin.

This indispensable reference includes photographs of eighty Tourte bows, new research and numerous documents previously unpublished.

François-Xavier Tourte was born in Paris in 1747 or 1748 and died in 1835, making him 87 years old then, a very long lifespan for his time. He entered the world during the reign of Louis XV and expired during that of Louis-Philippe, the “citizen-king.” In between he experienced the crowning of Louis XVI, the Revolution, the Terror, the Directoire, the ascent and reign of Napoléon Bonaparte, the Restoration that gave the nation Louis XVIII and Charles X, and the July Revolution that brought Louis-Philippe to the throne. Although we know little about his life (because, for one thing, the municipal archives were destroyed in the burning of the Hôtel de Ville during the Bloody Week in May 1871), we do know that his bowmaking practice continued unabated through uprisings and social shifts of every kind; examples of his work exist for every half-decade between 1770 and 1830. He was a highly specialized artisan whose labor was dedicated to music, a pursuit seemingly immune to social changes whether they came from the top or the bottom.

We have only two addresses for Tourte: he lived on Rue du Chantre (eradicated in the nineteenth century; on the present site of the Magasins du Louvre), from at least 1786 until 1806, when he moved his workshop to Quai de l’École, on the Right Bank, just upstream from the Louvre in the parish of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois; the street was eliminated in 1868 during the rearrangement of the city by Baron Haussmann. (He died on the Left Bank, on Rue Dauphine.) We know that Tourte’s father, Nicolas-Pierre (circa 1700-1764), was a luthier and very likely a bowmaker, and presume that the younger Tourte received instruction in the art (his older brother Nicolas Léonard was also a bowmaker). Oral history tells us that François-Xavier was apprenticed to an horloger, working on watches and perhaps clocks. That helps place him somewhat: he was born into the artisanal class, which in his lifetime had two principal centers. The smaller and poorer stratum clustered on the Left Bank, in the parishes of Saint-Marcel, Saint-Jacques, and Saint-Victor. A luthier whose trade depended on the gentry, however, would be more likely to base himself on the Right Bank, in the artisanal stronghold of Saint-Antoine.

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine has since 1860, and not by accident, been divided between the Eleventh and Twelfth Arrondissements, Popincourt and Reuilly. The cut runs along its eponymous main street, which connects Place de la Bastille with Place de la Nation (Place du Trône in Tourte’s time). In its day it was a powerful political force; the “privileged” artisans of the district were solvent, well-informed, self-protective, organized, and capable of action. In 1792, in the second phase of the revolution, they identified themselves as sans-culottes; that is, they wore long trousers instead of the knee-length breeches tradition had assigned them, and on their heads flopped the red Phrygian cap, a symbol of liberty. They remained symbolic of the popular essence of the revolution even after they were defeated in combat by the army two years later. Their descendants arose again and again in later years, for example in the nearly annual uprisings, some more localized than others, that marked the reign of Louis-Philippe, from his coronation in 1830 to his abdication in 1848. They reemerged for the Commune of 1871, the Popular Front, and innumerable strikes and demonstrations until the 1960s, when the belated second phase of the rearrangement of the city was undertaken and the district’s demographics began to shift significantly.

Tourte was a highly specialized artisan whose labor was dedicated to music, a pursuit seemingly immune to social changes whether they came from the top or the bottom.

Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois

It is a challenge for us now to imagine Paris as it was then, before Haussmann’s reconfiguration—before the great avenues were cut through and lined with their now-characteristic Second Empire houses, when the city was a labyrinth, poorly understood by nearly everyone. It is said that Marie-Antoinette’s flight to Varennes in 1791 was delayed because her coachmen could not find their way through the maze of streets, and no one could produce a map (the great Plan Turgot of 1739 was not exactly portable). People generally knew little of the city outside their immediate neighborhoods. The civic institutions that served the people in its entirety were few. There was Les Halles, the great marketplace that had seemingly always been there. There were the hospitals: the ancient Hôtel-Dieu and its adjacent Morgue on the Île de la Cité, and the madhouse, the Salpêtrière, on the Left Bank. There were the prisons: the fearsome Châtelet, the Bastille, Bicêtre, and Fort-l’Évêque. There was the Saints-Innocents cemetery near Les Halles, which had effectively become the city’s charnel house, since most parish graveyards were full, aside from the family crypts of the rich. And there was Place de Grève (now Place de l’Hôtel-de-Ville), which for centuries had been the site of public executions, a reliable source of entertainment for all classes. Otherwise people did not have much reason to leave their self-contained districts; inhabitants of the parish of Saint-Eustache had little idea of what lay in Saint-Germain-des-Prés or how to get there, and vice versa.

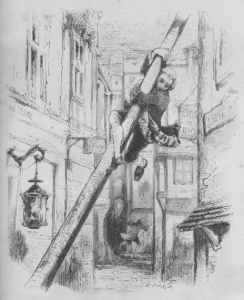

Some of the flavor of pre-Haussmann Paris can be gleaned from the photographs that Charles Marville was commissioned to make in the 1860s, as the city’s official photographer, recording many of the streets and neighborhoods scheduled for demolition under Haussmann’s orders. Among these can be seen, for example, the Butte-aux-Moulins, razed for the cutting-through of Avenue de l’Opéra; the tight alleys of the Cité; the medieval cluster of streets south and east of Les Halles. Although purposely taken at the break of dawn, when shops were closed and no tradesmen or washerwomen or idlers or beggars were around or at least visible, these pictures nevertheless convey a sense of what navigation was like, in streets barely wide enough for a cart to pass through, under overhanging stories of houses added to in ad hoc fashion over time, with the sun in many places only visible at high noon, so that muddy puddles formed and festered around the open sewers. But by the time of Marville’s photographs the city had already been subject to a number of revisions; the eighteenth century was far more chaotic. There are no photographs, for example, of Pont Neuf and Pont Saint-Michel when they were both lined end to end with houses, as tall and unstable as anything on land, which blocked the Milk Vendor breezes blowing along the Seine.

The streets themselves were, naturally, filthy. The sewers ran down the center of most of them, where gravity alone ensured that their flow, which included blood and offal from slaughterhouses, would run into the Seine. And there were horses and donkeys everywhere. Nicolas-Edmé Rétif de la Bretonne (1734-1806) notes that in Vienna and Berlin their dung was collected and used as fertilizer, whereas Paris squandered both potential profits and the health of the soil in the surrounding countryside by letting it accumulate in the streets.

The streets themselves were, naturally, filthy. The sewers ran down the center of most of them, where gravity alone ensured that their flow, which included blood and offal from slaughterhouses, would run into the Seine.

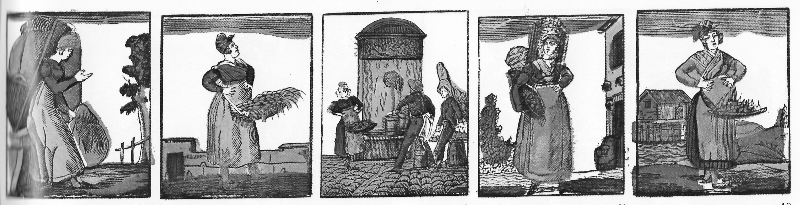

On the bright side, the streets were famous, at home and abroad, for their great symphony of cries—the rhymes, jingles, ditties, songs declaimed by the army of itinerant vendors. They resounded from the Middle Ages until about the time of World War I and were quoted in popular songs and depicted in engravings. People walked around with their bindles or their carts, hawking charcoal, firewood, fish, vegetables, chestnuts, rabbit skins, pewter, tin, old hats, carnival merchandise, announcing themselves in high, piercing voices. Likewise the ragman, the knife sharpener, the locksmith, the chimney sweep, the water carrier advertised their services; the watchman called out when he began his post. Some of the cries were brief formulaic phrases and some were songs with multiple verses, although by the eighteenth century there were so many of them at any given time that it became a cacophony. But, Louis-Sébastien Mercier (1740-1814) notes, servants had a tuned ear and would rush downstairs when they detected the appropriate tune, “distinguishing from the fourth floor what was being cried a block away, whether it was mackerel or herring, lettuce or beets.”

Washerwoman; Egg vendor; Water carrier; Vendor of English Pears; Seamstress 4. Boulevard du Temple, late 18th century

Society was then composed of eight classes: the nobles, the clergy, financiers, merchants, artists, artisans, laborers, and lackeys, which is to say the indigent. The bottom two classes, the workers and the poor, together accounted for 53 percent of the population in the late eighteenth century; in 1790 more than 100,000 were unemployed, destitute, receiving alms. The nobles and the bishops lived in palaces; the financiers in hôtels particuliers; the merchants and artisans in houses of proportionate size; workers in multi-family dwellings (per Mercier, struggling artists really did live in garrets); the poor in huts or cellars–or rented rooms from which they were evicted every three months for non-payment. The line between the classe laborieuse and the classe dangereuse–the workers and the poor–was fluid and porous, not to mention invisible to observers from the upper classes, for whom they and the artisans and even the lower reaches of the merchant class constituted an amorphous entity called “the people.”

The “privileged” artisans of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, the corps d’arts et métiers, could almost be called a rising middle class. They stood a full social step above the workers, who might be porters, day laborers, or for that matter artisans lacking the funds or connections to adhere to a guild. Many of the privileged artisans were literate, as distinct from their equivalents in the countryside; nearly all Parisian children had some sort of schooling, courtesy of the Catholic Church, which held the monopoly. (Not that the artisans were particularly devout; the densely populated faubourg contained, exceptionally, only a single parish.) They owned their houses, something fewer Parisians than ever were able to do, and they owned their ateliers, and they rented out space in one or both. They might be politically radical when the circumstances called for it, but culturally they were conservative.

The artisans occupied an odd social position, since they were inescapably part of le peuple, possessing no noble blood, inherited or purchased, and were generally not invited to enter the homes of their betters. Among the people, however, they were the aristocrats. They possessed very particular skills that were needed by the upper classes, so that they could be patronized only so far, and had to be paid fairly. The artisans were proud of their skills and of their role in society.

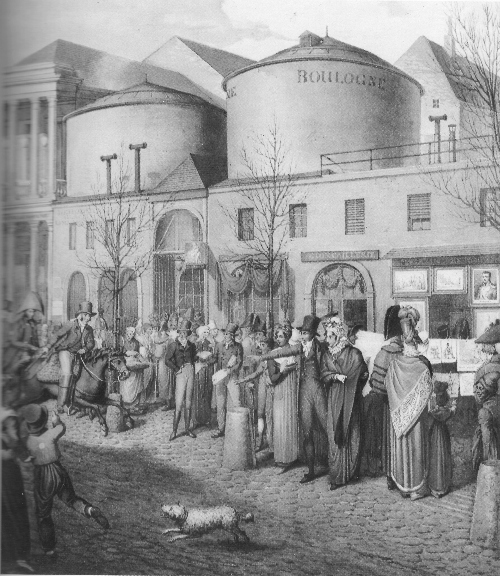

Boulevard du Temple, late 18th century

In 1675 there were 83 professions recognized by the guild system; by 1691 the number had risen to 129. Tourte and his father would have belonged to the grouping musiciens et facteurs d’instruments, which was eventually to be absorbed into the Académie Royale de Musique. The guilds, by mutual accord, set certain rules that applied to all the professions: the progress from apprenticeship to mastery, the pay scales that applied to the various stages, quality control, weights and measures. These were supplemented with rules of art specific to the professions. The guilds decreed that there would be no work done on Sundays or holidays, amounting to around 80 days off a year. They limited the numbers of masters, apprentices, and journeymen, proportionate to the size of the greater population. They fielded jurors, elected for two-year terms, who would visit the workshops, verify the quality of their output, and preside at annual ceremonies.

The guild combined many different functions. It was at once a sort of trade union and a masters’ protective association; it set and maintained high standards of quality, and fixed prices more or less generally; it often served as an intermediary between the crown and nobles and the broader public; it saw to members’ medical care and funeral expenses. But despite its esteem, long duration, and approval by the Church, the system came under attack beginning in the seventeenth century through the influence of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, minister in various capacities under Louis XIV, whose views on free labor and free trade resemble what we today would call liberalism, or neoliberalism. Laws were passed in the 1750s permitting journeymen to settle and work in any city they chose (besides Paris, Rouen, and Lille) and to freely establish guilds where none had previously existed, as well as mandating several endowed masterships in every guild for those, including foreigners, who did not possess the money or the blood ties to go through normal channels.

Rue Quincampoix

There was scarcely a year in Tourte’s life when peace and prosperity reigned. Economic and social pressures were unrelenting. Disturbances in the food chain were frequent, and the cost of living rose steadily.

Tourte, during his lifetime, saw one world end and another begin. Just how he experienced it is something we can only conjecture; the steady, artistically rigorous progress of his work, accomplished in the midst of every kind of social upheaval, is the only testament we have concerning his daily life. He was born sometime during the famine of 1747-48. Two or three years later there was a panic based on the rumor that children—especially children of artisans out on errands—were being snatched off the streets in broad daylight, either by perverts or by the police, who were seeking fresh bodies to populate Louisiana. The country was in perpetual turmoil. Louis XV was an autocrat, widely despised. In 1757 a former parliamentary servant went to Versailles and tried to stab the king; the culprit was executed on Place de Grève. In a Paris church in 1768 someone wrote above the baptismal font: “Pray to God for the king, who is deaf, dumb, and blind.” Louis XV finally died in 1774 and was replaced by Louis XVI, who immediately became “the good king.”

There was scarcely a year in Tourte’s life when peace and prosperity reigned. Economic and social pressures were unrelenting. Disturbances in the food chain were frequent, and the cost of living rose steadily. Street fighting was unpredictable and sudden; mass murders happened often enough to be a looming threat. But perhaps it could not have been otherwise, considering that the death of an old order and the birth of a new one can never be an easy passage. The monarchy, more or less an unbroken succession since the reign of Hugues Capet just before the turn of the millennium, died at least twice in Tourte’s lifetime—and not the monarchy itself alone but an entire culture of fealty and obligation, rituals and loyalties that could not be resurrected by any mere Restoration. The merchant class was accumulating wealth and power; they would dominate the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. And while all the upheavals were taking place, Paris was gradually being renewed, losing its medieval concentration and ad hoc non-planning, adding bridges, roads, and institutions at an accelerated pace. Modernity was just around the corner—three versions of what would become the bicycle made their debut around the turn of the century, and the steam engine was in the course of development. Somehow, through all of this, Tourte kept his attention focused, every day, on the precise crafting of his elegant pernambuco bows.

– Lucy Sante is a Belgium-born American writer, critic and artist.

Order an advance copy exclusively at www.magicbowpublications.com