Omobono Felice Stradivari (1679 – 1742) was the youngest son of the Cremonese titan Antonio Stradivari from his first marriage to Francesca Ferraboschi in 1667. Together with his elder brother Francesco (1671 – 1743), Omobono assisted his father in the workshop. Francesco had an eight year head start, and Omobono’s frequent and extended absences away from Cremona meant that his participation in the workshop was generally more sporadic and less evident until after 1700. One particular trip to Naples, which probably occurred during the year his mother died in 1698, accrued a large financial debt which had an unfortunate lasting impact on his relationship with his father. Nearly forty years later the debt was referenced in Antonio’s testament and given as the reason why Omobono received no inheritance whereas Francesco inherited the family business and the workshop.

Antonio directed the Stradivari workshop well into his 90s and throughout its colossal output several fundamental elements remain consistent. These include the forms and molds on which instruments were made, the classical Cremonese construction method, the placement of f-holes, the iterative architecture, and a spectacular varnish.

Instruments made solely by Omobono are extremely rare: only around ten are known that were made during Antonio’s lifetime, including the ‘Blagrove’ of c.1700, the ‘Tanocky’ of c.1710, and the ‘Josefowitz’ of c.1725-1730.

Left to right: the ‘Blagrove’ of c.1700, the ‘Tanocky’ of c.1710, and the ‘Josefowitz’ of c.1725-1730

Many instruments by Omobono were originally labelled “sotto la disciplina di Antonio Stradivari” (“made under the direction of Antonio”) however the scarcity of instruments that still bear these labels is perhaps the result of the unscrupulous practice of dishonest individuals upgrading these violins to the work of Antonio for commercial gain.

Twenty-first century research and expertise together with the careful cataloguing and analysis of Stradivari instruments challenge the historically-held opinion that Omobono’s involvement in the Stradivari workshop was less significant than Francesco’s. The few outstanding instruments which Omobono made on his own, as well as the many distinguished violins by Antonio that show Omobono’s unmistakable assisting hand, are testament to Omobono’s unequivocal contribution to the genius of the Stradivari workshop.

It’s easy to imagine Omobono’s ‘rebellious’ character reflected in his making style. Omobono’s soundholes are set in the same way geometrically as Antonio’s but appear less controlled and almost ‘del Gesù-like’ due to their straighter inner lines, wide upper and lower wings, and a more pronounced radial swing out of the upper and lower eyes. His treatment of corners shows little attempt to create a perfectly-refined miter, practically abandoning the delicate extensions known as ‘bee-stings’. Perhaps lacking the uncompromising perfectionism of his father, Omobono instead opted for a more functional joining of the purfling which resulted in shorter and more outward facing corners.

Above: Omobono’s f-holes feature wide upper and lower wings, and a more pronounced radial swing out of the eyes. Their robust appearance is further exemplified by the slanting of the f-holes outwards, and their internal lines running parallel, almost resisting to taper into the extremities.

Omobono’s purfling produces a harmonious classical outline but it is generally rather rugged in appearance. With the purfling set further in, the edge appears bolder and the overall powerful impression is bolstered by the omission of fluting at the edges. The arching is flatter across the bouts and generally fuller as was typical of the Stradivari workshop in the 1720s and 30s. Violins from this period are known for their outstanding tonal properties and include the ‘Abergevanny’ of 1724 formerly used by Leonidas Kavakos, the ‘Wilhelmj’ of 1725 in the collection of the Nippon Music Foundation, the ‘Dragonetti, Milanollo’ of 1728 (ex-Christian Ferras) played by Corey Cerovsek, the ‘Reynier’ of 1727 (ex-Salvatore Accardo) owned by LVMH, and the ‘Kreutzer’ of 1727 on which Maxim Vengerov performs.

Below: Omobono’s treatment of corners shows little attempt to create a perfectly-refined mitre, practically abandoning the delicate extensions known as ‘bee-stings’. He instead opted for a more functional joining of the purfling which resulted in shorter corners.

Omobono’s scrolls follow the same general profile as Antonio’s, albeit with a higher and deeper throat and of slightly more generous proportions. The concentric turns don’t quite reach Antonio’s level of balance but are unmistakably in keeping with Cremonese traditions. The turns are deeply carved and show the unashamed tool marks which one might be inclined to associate with the Guarneri family. Each turn on the bass side becomes shallower and shows finesse, whereas those on the treble side are equally deeply undercut with the final turn rather gaping. Despite these attributes generally contributing to a wilder appearance, Omobono’s scrolls still bear a close resemblance to his father’s.

The bass and treble sides of the scroll of the ‘Josefowitz’ flanked by those of the ‘Da Vinci’ of c.1714. Omonono’s scrolls feature a higher and deeper throat and are of slightly more generous proportions. Each turn on the bass side becomes shallower, whereas those on the treble side are equally deeply undercut with the final turn rather gaping.

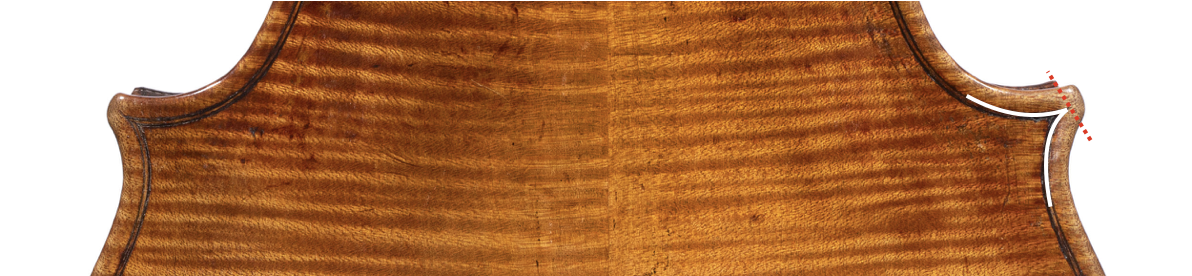

Stradivari instruments from 1724-1728 are often made with a local Italian maple known as ‘oppio’ which features a distinctive narrow curl. The stunning two-piece quarter-cut oppio back of the ‘Josefowitz’ helps to corroborate the date of manufacture to the 1725-1730 period.

Violins by Antonio Stradivari sharing the same billet of maple as the ‘Josefowitz’:

Above: the ‘Reynier, Regnier’, the ‘Halphen, Benvenuti’, the ‘Holroyd’ all of 1727

Below: the ‘Barrère’ of 1727, the ‘Koeber’ of 1725, the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ of 1726

Dendrochronology conducted by Peter Ratciff dates the latest ring of the bass and treble side of the table to 1710 and 1716 respectively. Significant cross-matches were found to numerous instruments by Stradivari including the 1724 Abergavenny, 1725 Duke of Cambridge, 1724 Von Seldeneck, 1724 Sarasate, 1725 Hammig, 1726 Hilton and others.

David Josefowitz with the Princess Royal at the opening of the David Josefowitz Hall at the Royal Academy of Music in 2001. Photo from the Guardian newspaper.

This violin takes its name from its former owner, the renowned entrepreneur, instrument and art collector, and philanthropist David Josefowitz who passed away in 2015. His landmark collection comprised several notable Stradivari and Guarneri including the ‘Crespi’ of 1699, the ‘Joachim’ of 1698, the ‘Regent’ of 1708, the ‘Segelman’ cello of 1692, the ‘Markevitch’ cello of 1709, the ‘Kux, Castelbarco’ viola of c.1720, the ’de Bériot’ of 1744, and many others.

During the early 2000s, this violin was on extended loan to the Royal Academy of Music in London, whose concert hall also bears the Josefowitz name.

This historic and rare violin will be offered as the highlight of Tarisio’s March 2024 auction in London.