Philip J. Kass and Andrea Zanrè are the authors of the much anticipated forthcoming book Liuteria Mantovana. Based on extensive new research and featuring photographs of over 150 instruments, this important reference will be released in the autumn of 2022. This week, I spoke to them about their research, and about Balestrieri in particular.

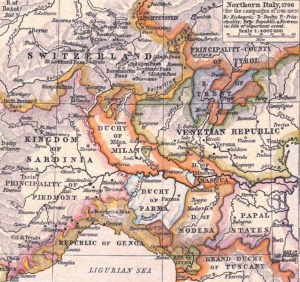

Northern Italy in 1796.

Jason Price: Mantua is only sixty kilometers from Cremona and yet its violin making culture developed very differently and much later than that of Cremona. Why?

Philip J. Kass and Andrea Zanrè: Sixty kilometers and a world away! Until 1707 Cremona and Mantua were in two entirely different countries. Mantua certainly had a head start over Cremona so far as music was concerned, but while it remained fairly well-heeled, by the heyday of Nicolo Amati its greatest years were in the past. Violin making as we know it was exported to Mantua from Cremona in the person of Pietro Guarneri in 1680.

JP: Tell us about the importance of Pietro Guarneri?

PJK & AZ: Pietro was both a violinist and violin maker. He relocated to Mantua in late 1679 to pursue musical opportunities and in doing so, introduced Cremonese violin making to a city that otherwise does not appear to have had adequate financial support to sustain a violin making workshop. This seems to have been the case for future generations as well. However, the fact that Pietro was one of a handful of the greatest violin makers to come out of Cremona meant that he cast an enormous shadow over everything that followed him stylistically and aesthetically, and it is his presence that makes subsequent Mantuan violins so readily identifiable as being Mantuan.

It is Pietro’s presence that makes subsequent Mantuan violins so readily identifiable as being Mantuan

JP: How was the musical environment different in Mantua than, for example, Cremona or Milan, and how did this affect the development of Mantua’s violin making culture?

PJK & AZ: Mantua’s musical environment was in decline throughout the 17th century, at least so far as stringed instruments were concerned, and that seems to have been the case until the last Duchessa began actively supporting a Court ensemble. It was into this ensemble that Pietro Guarneri was admitted in 1685. However, violin making seems primarily to have been for internal use. By contrast, Cremona, a part of the Duchy of Milan, had the vigorous Milanese musical environment for support, not to mention the international acclaim of stringed instruments made in Cremona.

JP: Which soccer team is better? Mantova FC or U.S. Cremonese? (Just kidding! We don’t have to do that…)

PJK & AZ: We found no documents in the Archivio di Stato to help us clarify this point, but our favorite bars in Mantua seemed very much to favor the local team.

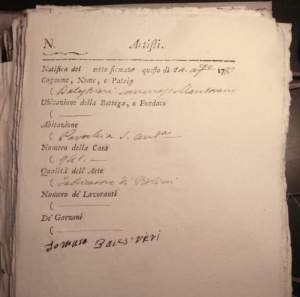

A document from Mantua’s Camera di Commercio bearing Balestrieri’s signature stating he was registered as a “Fabricatore di Violini” in 1787.

JP: Let’s talk about Balestrieri: what did you learn about him from your research?

PJK & AZ: Where does one begin? Mantuan violin makers seem to have been consistently misrepresented in historical accounts, down to their actual dates of activity! So nothing prepared us for the discovery that, with two striking exceptions, none of the violin makers working between the 17th and 20th centuries were actually born there. We were not expecting Balestrieri to be from a village outside of Piacenza, nor for his profession to have been as a valet. His change in profession once Camillo Camilli succumbed to his final illness fits well with the pattern of the town. Similarly, we were unable to find evidence that any of our subjects, except for Pietro Guarneri, came to Mantua already trained as violin makers. However, we also noted that Balestrieri was the most productive Mantuan violin maker of the 18th century, which certainly reflected the changing musical tastes and instrumental requirements that the new repertoire necessitated.

Mantua’s Palazzo Canossa. When he first arrived in the city, Balestrieri worked as a footman in the building on the left.

JP: His labels tell us he is from Cremona, what can you tell us about that?

PJK & AZ: Balestrieri had to have been aware of the magic of the neighboring town so far as violin making was concerned. His “Cremonensis” labels date from the 1760s, at the same time as Guadagnini was making a similar claim on his labels. Whether it was true is hardly the point; for Pietro Guarneri, this was a statement of fact, but for Balestrieri and Guadagnini, it probably made perfect sense from a marketing standpoint.

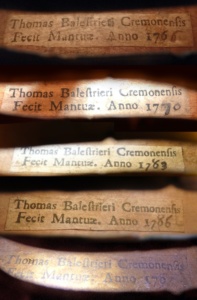

JP: So Pietro Guarneri wrote “Cremonensis” on his labels and that was legitimate, but Balestrieri was just posturing. Balestrieri was certainly ambitious and hard working. What can you tell us about the “176_” label?

PJK & AZ: We can point to three important makers who, overestimating their output, had three digits printed on their labels rather than the more prudent two: Stradivari (in the mid-1660s, with “166”), Pietro Guarneri (in 1700, with “170”), and Balestrieri (in the early 1760s, with “176”). They all had to make adjustments. Pietro dealt with this by handwriting a Cremonese 1 on top of the 0; Stradivari and Balestrieri both used the same work-arounds: scraping off the 6 (in Balestrieri’s case, sometimes incompletely); adding an upper loop to the 6 in the ‘80s, and scraping off the top of the 6 and adding a tail to make it a 9 in the ‘90s. We’ve seen several untouched labels from the 1770s which actually still show the 6 and thus had five digits (which might be the reason for several “circa 1767” datings we’ve heard over the years), and no doubt, eventually a fair number of those instruments either had the job more completely done or had the label changed entirely.

Both Balestrieri and Guadagnini are among the first makers of their generation to actively imitate the outline and arching of Stradivari’s later works, putting them in the vanguard as the end of the century approached

The five images above show various workarounds that Balestrieri used to make his 1760’s label last through the 1790s.

JP: The 18th century was a time of tremendous change in music making and also in lutherie. Is it fair to say that Balestrieri was on trend for most of his career?

PJK & AZ: As with the larger community of makers working during the 1750s and 1760s, it also dawned on Balestrieri and, at the same time, Guadagnini, that the future of music-making was better served by Stradivari’s ideas regarding tone and construction than on the patterns which had served so well until then. Both are among the first makers of their generation to actively imitate the outline and arching of Stradivari’s later works, putting them in the vanguard as the end of the century approached. And, in the personal and regional way that enables us today to recognize the local origins of so much Italian violin making of the time, both Balestrieri and Guadagnini found quite different answers from the same sources.

Mantua’s Teatro Bibiena. The inauguration in 1770 coincides with the date of the violin in the March auction. W. A. Mozart gave a performance there that same year — perhaps Balestrieri was lucky enough to be among the standing crowd.

JP: One of the remarkable things about the Mantuan tradition of violin making is its achievement of excellence even though the tradition itself is fragmented with little or no continuity from generation to generation. In comparison with the father to son, teacher to student tradition of Cremona, Milan, Venice, etc, does Mantua qualify as a different type of “tradition”?

PJK & AZ: The evolution of lutherie in Mantua follows a pattern much more familiar to countries like the United States than it does Italian traditions, although we note that this looks increasingly to have been the way of Italians when you leave the major urban centers. Violins were made by people who were interested in them, when they were needed, and wherever they were needed. Training in the craft simply required a basic understanding of woodworking, and so anyone with rudimentary carpenter’s skills could tackle the task. They would invent their own procedures, but they would base their work upon some existing model, copying the structure and appearance as best they could. Mantua stands out particularly because the archetype for all future violins was the work of one of the craft’s greatest artists, with a very distinctive personal style, and all later work from that town pays homage to Pietro Guarneri, with each maker selecting particular characteristics to highlight and developing personal work-arounds for construction. So, while each one reaches strikingly different end results, all of their work is linked by the looming presence of Pietro, and this, plus the use of local materials, gives them their consistent family resemblance.

Violins were made by people who were interested in them, when they were needed, and wherever they were needed

JP: And then finally, we’re all waiting for your book to come out. When will the book be released and what should we expect?

PJK & AZ: Working on this book has been a labor of love for both of us. Mantua was a city with a very distinct local style that had never been properly researched, so we hoped there would be significant discoveries. And luckily we found this to be true, so much so in fact that it required a complete rethink of the instruments emanating from there and the proper manner of identification, attribution, and dating, something very much needed, not just for Mantua but for the entire violin culture of that era. And, in the course of study, we developed a very strong affection for the town, its style and manners, and can’t imagine visiting Italy without returning there again. But when will it come out?? The work has grown to three volumes, so as to encompass the entire school, and this takes time. We are hoping that COVID-19 puts up no further delays for us so that we can have it available by the autumn of 2022.

A Highlight of the March Auction: a violin by Tommaso Balestrieri

This violin dating from 1770-72 is the highlight of our March auction, which ends on the 25th, and is illustrated in the forthcoming book Liuteria Mantovana by Philip J. Kass and Andrea Zanrè. You can watch my feature on this lot here: