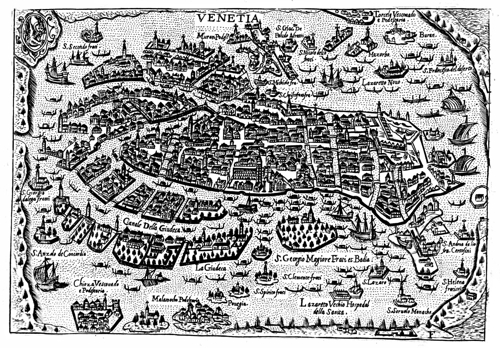

Bertelli map of Venice dated 1629, 20 years after the publication of L’Orfeo

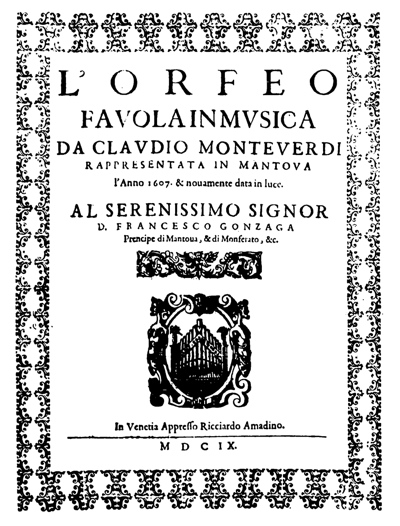

With the premiere of his opera L’Orfeo in Mantua in 1607, the Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi created a sensation in Renaissance Italy. In L’Orfeo Monteverdi fused the instrumental component of opera with the dramatic action in the libretto in an unprecedented way. The success of L’Orfeo assured Monteverdi’s ongoing success and influence, and the world of music, especially opera in Northern Italy, would be forever changed. The style advanced by Monteverdi is rightly credited as marking the transition to the Baroque era, creating music that ultimately would replace the viols of the Renaissance with modern-style violins, violas and cellos. The superb instruments of Matteo Goffriller and his followers were a direct response to unprecedented commercial demand in Venice resulting from this musical transition.

Monteverdi (1567–1643) was one of the first composers to develop an avant-garde style of composition known as basso continuo, which represented an expanded role for bass instruments including the bass viol, an early precursor of the cello. In the instrumentation for L’Orfeo, published in 1609, 10 of 14 string instruments indicated are viole da braccio, often playing in the range of the modern cello. This expanded role for bass instruments and the increased mobility of the basso continuo style would become trends, and the cello ultimately proved far better suited to the range and flexibility called for in this emerging music. By the end of the 17th century the cello was increasingly the instrument of choice, while the viole da braccio was nearly extinct.

L’Orfeo frontispiece; the opera created a sensation in Italy

Monteverdi’s appointment as Maestro di Cappella or head of the choir at San Marco Cathedral in Venice in 1613 gave him the necessary artistic authority and fiscal means to double the size of the ensemble there from 12 to 24 players over the years of his tenure. The trend toward larger ensembles at San Marco didn’t stop with Monteverdi. One of his eventual successors as Maestro di Cappella, Giovanni Legrenzi (1626–1690), increased the number of musicians in the ensemble to 34 when he took over in 1685, and replaced viol players with violinists and cellists. Legrenzi’s appointment at San Marco might have been directly connected to Matteo Goffriller’s arrival in Venice the same year, which would be easy to understand in the context of a pressing order from an important client.

The popularity of the musical arts in 17th- and 18th-century Venice can’t be overstated. Unlike other Italian states, in the 18th-century Venetian Republic secular music was successfully commercialized and fees charged for attendance. The numerous churches in the city also employed musicians for sacred services, particularly on feast days, while musical performance became highly prized at hospices for orphans such as the well-funded Ospedale della Pieta, which maintained a substantial inventory of instruments. Demand for opera, an emerging new form, was particularly strong, indicated by the early commercial success of the San Cassiano Theater, which opened in 1637, and spawned the eventual opening of over a dozen more theaters in the city.

As a principal amusement for people from a variety of backgrounds, and no longer just for the nobility, music performance was a lucrative business, generating huge demand for new instruments. The demand appears to have been met almost entirely by local production, carried out by a tight-knit group of highly skilled craftsmen, most of whom moved to the city from the Tyrol and Füssen to the north to take advantage of the flourishing economy in Venice.

Matteo Goffriller

Born in Bressone in the Tyrol, Matteo Goffriller (1659–1742) was already well trained as a violin maker by the time of his arrival in Venice in 1685. He was the first truly great violin maker to emerge from a group of German artisans who were attracted to Venice by the growing local demand for instruments. Goffriller was welcomed to the city by a former employer of his sister, violin maker Martin Kaiser (1642–c. 1695). The community of instrument makers in Venice included others in addition to Kaiser, but Goffriller’s bold and inspired concepts, technically strong work and extraordinary varnish quickly set him apart from the efforts of his local contemporaries. He soon emerged as the dominant maker in the city, establishing a standard for Venetian violin making that would continue to be felt by successive generations after him. A year after his arrival in Venice, Goffriller married Kaiser’s daughter Maria Maddalena, strengthening his commercial and personal ties to the mostly German instrument making community in the city.

Goffriller cello from the early 1700s. The high quality of his output attests to his dominant position in Venetian violin making

While it is presumed that he must have been active building instruments from his arrival in Venice in 1685, Goffriller delayed joining the Ordine dei Marzeri, the Venetian guild that levied taxes on instrument makers for as long as possible, presumably to avoid paying these taxes. In 1689 he officially joined the Marzeri and assumed ownership of an existing musical instrument shop located at Canareggio, Calle di Ca’ Dolphin, no. 687 from violin maker Michael Straub. Started by the instrument maker Cristoforo Coch some time before 1638, the business at Calle di Ca’ Dolphin was in an advantageous location next to the theater S. Giovanni Grisostomo, a house known for playing to upper-class Venetian society.

Label of the Goffriller cello. Under UV light the date appears as either 1701 or 1710

Kaiser lived and worked alongside his son-in-law at Calle di Ca’ Dolphin probably from 1691 until around 1693. Even after joining the Marzeri guild, Goffriller appears to have understated his production by comparison with some of his contemporaries, presumably in an effort to reduce his tax burden. A different story about his success can be gleaned from the many surviving Goffriller instruments, all of high quality and fine material, often somewhat experimental in form and dimensions. This substantial output attests to Goffriller’s creative genius and his position as the dominant force in musical instrument building in Venice from around 1690 until the emergence of Domenico Montagnana around 1725. Goffriller’s output began to wane in the 1720s and by the mid-1730s health problems left him an invalid, unable to work through to the end of his life in 1742.

Goffriller built many fine violins and a few excellent alto-sized violas, but is best known for his magnificent cellos. Since their creation, these cellos have been sought by the top tier of performers, alongside those of Montagnana and Antonio Stradivari from Cremona. In a pioneering career spanning some 40 years in Venice, Goffriller’s enduring influence left an indelible mark on the city’s musical community. In particular, his answer to the demand for cellos in post-Monteverdi Venice was a heroic success. After Goffriller, the city would forever be associated with the creation of some of the greatest cellos of all time.

Further reading

Goffriller violin c. 1700. From 1689 his workshop was advantageously situated next to the theater S. Giovanni Grisostomo

More photosViolin and Lute Makers of Venice 1640–1760, Stefano Pio (Venice Research, Venice, 2004)

Music in the Baroque Era, from Monteverdi to Bach, Manfred F. Bukofzer (Read Books LTD, 2013)

Monteverdi in Venice, Denis Stevens (Associated Universities Presses, 2001)

Les Violons: Venetian instruments, paintings & drawings, Jaeger, Schmitt, Graff (Association pour la Promotion des Arts, Hotel de Ville de Paris, 1995)

The Sellas Family of Violin and Lute Makers, Stefano Pio (Journal of the Violin Society of America, Vol. XX, No. 2, 2006)

Monteverdi’s violini piccoli alla francese and viole da brazzo, David D. Boyden (Societe de Musique D’Autrefois, Neuilly-Sur-Seine, 1963)

The History of Violin Playing from its origins to 1761, David D. Boyden (Oxford University Press, 1965)

Domenico Montagnana: ‘Lauter in Venetia’, ed. Carlson, Cacciatore and Neumann (Cremona, 1998)

www.hoasm.org/VB/VBMonteverdi.html

Stefan Hersh is a violinist, appraiser and expert, and a partner at Darnton & Hersh Fine Violins, Chicago