Included in our March 2019 sale in London are 14 lots of documents and correspondence between the Marseille luthier Marius Richelme (1833–96) and various members of the trade, collectors and musicians. These illuminate the working life of a provincial luthier in 19th-century France, from his apprenticeship to his various business ventures, and offer rare insights into the context in which the most important French workshops flourished. Looking at these from a 21st-century perspective, one can’t help but note that while some aspects of the trade have drastically changed, some others haven’t at all!

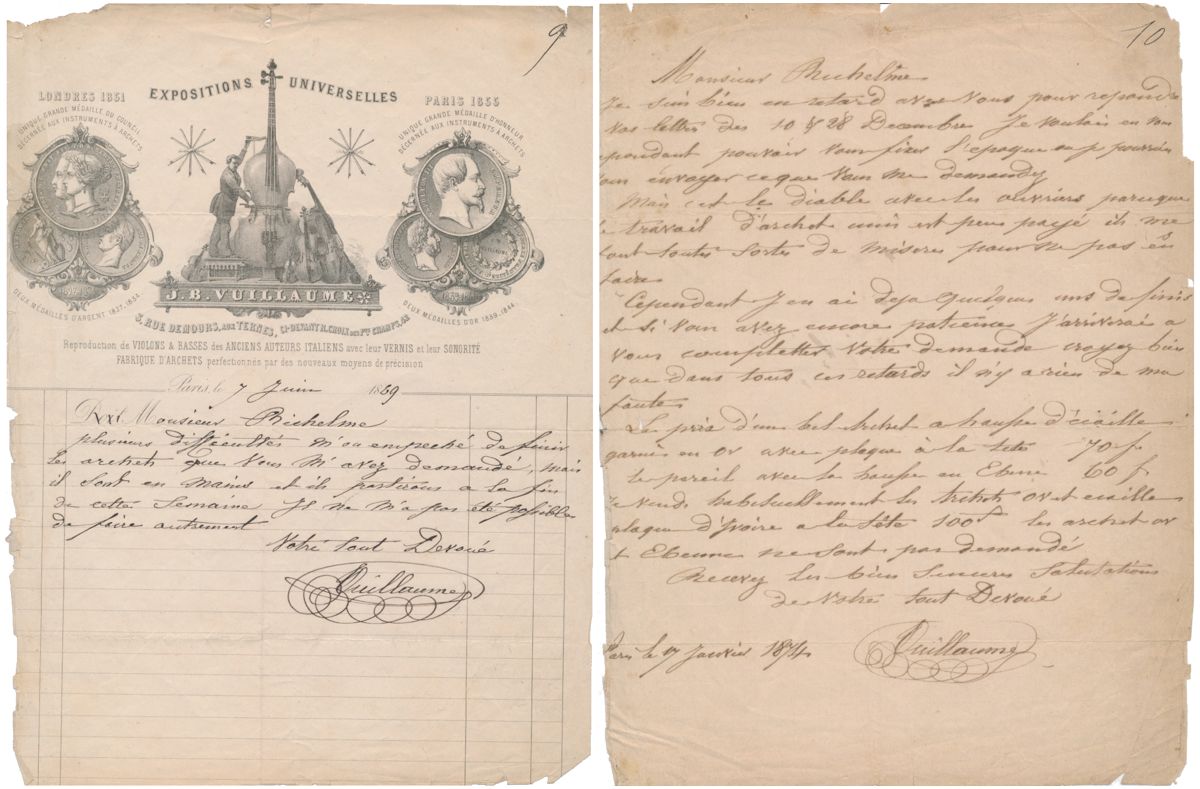

Two letters from Vuillaume to Richelme. In 1874 he writes: ‘If you still have patience left, I will be able to fulfil your order – please believe this delay is no fault of mine’

How sweet the 40-hour week seems compared with the working hours described in Richelme’s apprenticeship contract in 1850: ‘[…] every day except for Sundays, from 6am until 8pm during winters, and until night-time during summers and starting at 7am’! Bow makers’ status seemed particularly dire, even when employed in the most prestigious workshops, as Vuillaume reveals in his letter of 1874, complaining that ‘bow work is cheaply paid and the workers play all kinds of tricks on me to avoid doing any of it.’

‘Bow work is cheaply paid and the workers play all kinds of tricks on me to avoid doing any of it’ – J.B. Vuillaume

The ratio of prices has also changed since then. An ivory plate almost doubled the price of a bow, according to Vuillaume: ‘A nice bow that is gold and tortoiseshell mounted is 70 francs, the same with an ebony frog is 60 francs. I typically sell gold and tortoiseshell mounted bows with an ivory headplate which makes them 100 francs.’ Also notable is the fact that according to Vuillaume himself, his Maggini models are offered at the same price as Stradivari, Amati and even Guarneri models! Today, Vuillaume’s Guarneri models can sell for as much as $350,000, whereas Maggini models typically sell for about ten times less.

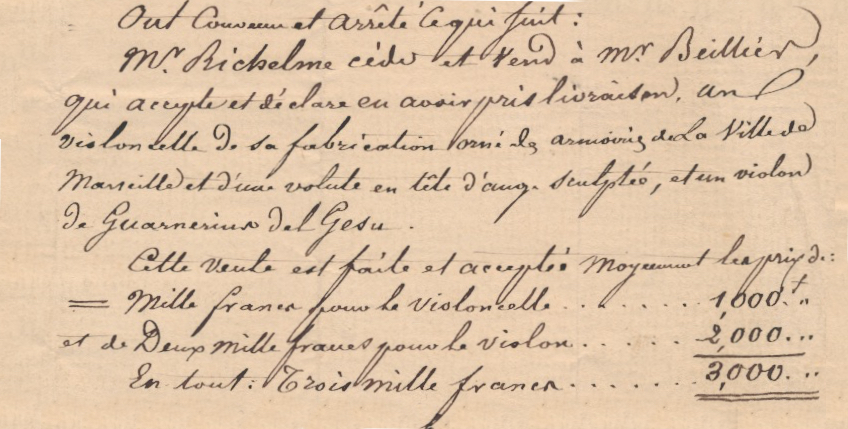

This Ernest Beiller bill of sale shows that a ‘del Gesù’ was only double the price of a modern cello

There is also a bill from F.N. Voirin showing that Voirin bows were slightly cheaper than unnamed bows made for Gand & Bernardel, while a bill of sale dated 1873 shows that a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ violin was sold for only twice the price of a modern cello!

In fact, it transpires that Italian making (or any non-French making, for that matter) was not always as revered in 19th-century France as it is today: one teacher, M. Mournier, describes Italian instruments as ‘Macaroni violins which will have expired in 50 years,’ while the Antwerp music shop owner G. Faes mentions how much more he appreciates Richelme’s instrument-making after seeing three Stradivari violins, three Amati instruments, and ‘a Dutch violin of the last century of an unpleasant shape.’ This perhaps explains the casual ease with which some experts at the time attributed works to various Italian makers!

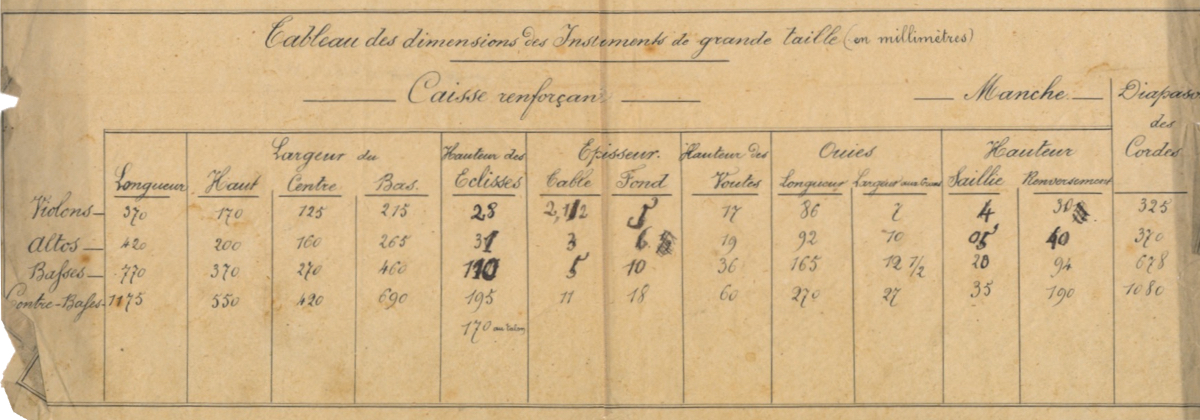

In a century very much turned towards technological advances, we also find comments in the local press deploring how stiff and old-fashioned the violin making milieu was, and praising Richelme for his new model for instruments of the string quartet, and his use of the new science of acoustics. For example in one press clipping from 1893 the violinist Lucien Poujade writes: ‘Mr. Richelme has just attained the perfection of Art by creating a marvelous modern violin to which he applied his recent discoveries in acoustics, and a perfected varnish from the Cremonese makers.’ Twenty years earlier, in a letter from 1873 Frederic Gailars, solo violinist at the Grand Theatre of Toulouse, congratulates Richelme on ‘going against the old ideas and creating a pretty new model.’ Indeed, both Vuillaume, who worked closely with French physicist Félix Savart, and Richelme experimented with materials and forms, and were invited to exhibit instruments at the famous French Expositions. The use of new technologies has continued in workshops today, with 3D-modeling, microscopic varnish research and dendrochronology studies all used by 21st-century makers.

‘I have serious and founded doubts about the success of your enterprise: you are about to face a jury of sold-out men!’ – G. Lemarié

Another crucial aspect of the trade seems to have presented similar challenges to Richelme as it does today: networking. In 1869 Richelme received a letter from a G. Lemarié, who writes: ‘It is my pleasure to recommend you to my illustrious master Alard, but […] he is the son-in-law of Vuillaume […] and an intimate friend of the Gand house. No matter your merits and the superiority of your instruments […] I have serious and founded doubts about the success of your enterprise: you are about to face a jury of sold-out men!’

Richelme (right) and one of his innovative violas, which some of his contemporaries preferred to classical models

Other letters corroborate Richelme’s quest for support among influential musicians and teachers, and for official recognition. In 1870, both the Ministre des Beaux-Arts, Maurice Richard, and the Director of the National Superior Conservatories of Music, Dance and Drama in Lyon, Daniel Auber, accept his request for them to examine his instruments. Meanwhile in a letter of 1877 the Hungarian violinist and composer Eduard Reményi apologises for not being able to help advance Richelme’s instruments at the Opera Comique: ‘I have no influence in musical corporations, and one must have an official position to succeed in such an endeavour. I therefore advise you to contact M. Chouquet at the Conservatoire National de Musique.’

More practically, courier shipping via train (the 19th-century version of FedEx!) appears to have been widely used, even for top instruments: ‘The Stradivarius arrived in perfect condition,’ writes André Chardon, who compliments Richelme on his packing. And it is refreshing to see that, despite being an exemplary businessman, Vuillaume was prone to mistakes in fulfilling orders and being late in completing them (‘I misread the number 4 you wrote, and took it for a 7. This is why I sent 7 bows instead of the 4 you asked for…’ he writes in 1868), just like anyone else!

Marie Turini-Viard is Tarisio’s London-based specialist.

To view full details of the Richelme correspondence, see Lots 1–14 of our March sale. Bidding ends on March 18.