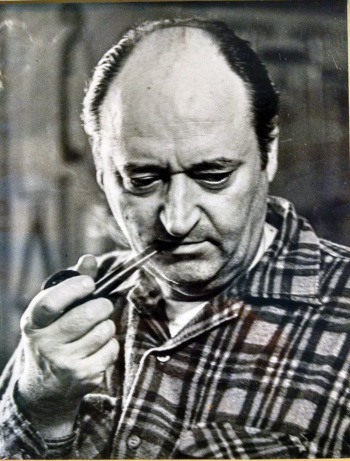

D’Attili wrote in a final letter to Schaff: ‘All of my certificates begin with “In My Opinion.” I am just one man with one mind and one set of experiences.’ Photo courtesy Hans Nebel

From 1990 to 1992 I had the good fortune of spending a lot of time with Dario D’Attili. I had moved from the Upper West Side of Manhattan to my first real house, across the Hudson River in Englewood, New Jersey. I had met Dario once or twice before and had been impressed by his generosity of spirit and attention. It had long dawned on me that the people most needing education about instruments and bows were the people who made their living playing them. At the time there were surprisingly few resources for learning; a handful of expensive reference books and a few publicly accessible collections of instruments.

Dario proved to be a great teacher and a generous mentor. If you expressed a genuine interest, Dario would take your instrument and explain what he was seeing, slowly navigating the many twists and forks in the road, with an occasional glance to see if you could follow, and self-deprecating humor if you couldn’t.

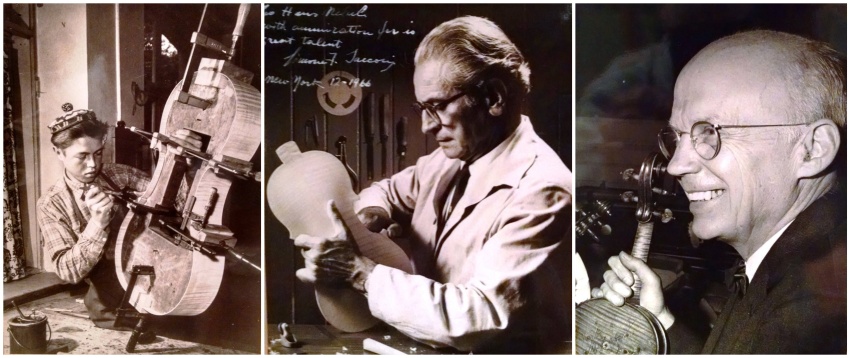

Dario D’Attili was born in Rome on March 26, 1922 into a musical family. His father was a lawyer by profession, but gave it up to follow his passion for teaching music. Dario’s two siblings became professional musicians after the entire family moved to New York City in 1935. Meanwhile Dario, who expressed more interest in making violins than playing them, was brought to the shop of Emil Herrmann to learn from the eminent Italian maker and restorer Simone Sacconi. Frustrated by the 15-year-old’s inability to use tools, Sacconi ordered young Dario to apprentice to the Venetian émigré, Jago Peternella. After more than a year of unpaid apprenticeship (‘I rehaired a lot of bows’), Dario returned to Sacconi only to be told that everything he had learnt ‘must be undone’. Thus began the legendary affiliation between Sacconi and D’Attili, identifying, restoring and selling the finest string instruments in the finest shop in America.

D’Attili served in the US Army in the Pacific during the Second World War before returning to the Herrmann shop, which had benefitted from the influx of fine instruments brought over by European émigrés. In 1951 Herrmann closed the New York shop and both Sacconi and D’Attili joined the four-year-old business of Rembert Wurlitzer, whose passion for rare stringed instruments was so great that in 1947 he had bought out the stringed instrument division of the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company from his father. A genteel and scholarly man, Rembert received his most important training from Alfred Hill. His respect for the history and provenance of instruments, along with a photographic memory, was an excellent foil for Sacconi’s prowess at identification based on the technical aspects of construction.

Over the next few years the new Wurlitzer shop, located across from Carnegie Hall, boasted a who’s-who list of great restorers and future experts. Jacques Francais had recently left to start his own shop, buoyed by the legacy of his father’s business, whose linage traced back to the shop of Nicolas Lupot in the late 1700s. William Salchow worked on evolving his personal model of bows, in addition to restoration. Frank Passa, Vahakn Nigogosian, Luiz Bellini and René Morel all shared the bench. In 1957 18-year-old Hans Nebel was hired by Wurlitzer and Sacconi, and Charles Beare spent some time there in the early 1960s honing his skills while training his eye. Later talented hires included Roland Feller, Robert Cauer, Carlos Arcieri and David Segal. With Sacconi heading the workshop and D’Attili as foreman, Wurlitzer’s shop was the first and last port of call in the American fiddle trade.

In 1951 D’Attili joined the workshop of Rembert Wurlitzer (right), which employed a who’s who list of talented restorers and future experts, including Hans Nebel (left) and Simone Sacconi (center). Photos courtesy Hans Nebel

After Wurlitzer’s sudden death in 1963, Sacconi, D’Attili and head salesman Harry Duffy would sign off on new certificates. Sacconi’s health issues led him to work increasingly from his home in Point Lookout, Long Island, and in 1964 D’Attili was appointed general manager of Rembert Wurlitzer Inc. In 1968, on the advice of Sacconi and D’Attili, Nebel became foreman as the last chapter of the Wurlitzer shop unfolded, ending with its sudden closing on August 1, 1974.

With their forced independence, the Wurlitzer staff dispersed. All the others set up workshops and dealerships either alone or in partnership except for D’Attili, who chose to work close to home, literally in his basement in Dumont, New Jersey. Rather than deal in instruments, sell accessories and rent retail space, he applied his restoration skill, expertise and boundless curiosity to working on selected projects, writing certificates and experimenting with varnish recipes, all under the close supervision of his wife, Maria. He was a founding member of both the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers and the Violin Society of America (VSA). As a school of violin making had recently been established in Salt Lake City, the VSA hoped to create a school of violin restoration on the east coast. It was to be headed by Dario D’Attili and Hans Nebel. Sadly, this was not fated to happen.

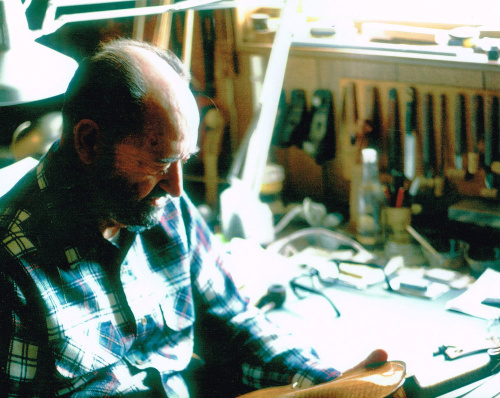

D’Attili assessing a Pietro Guarneri violin. When attributing instruments, he would not force an answer. Photo courtesy Hans Nebel

I don’t remember what instrument I first nervously showed this world-class authority, but it was undoubtedly unimpressive; probably a Tyrolian fiddle aspiring to be from the southern side of the Alps. I had also become fascinated with bows, having recently acquired a copy of Etienne Vatelot’s two-volume book on French bow makers. When I mentioned reading up on bow makers from Vuillaume’s shop, Dario’s eyes lit up. ‘I love bows! When I really want to enjoy myself, I don’t look at fiddles. I look at bows.’ Dario had an impressive collection of bows, which became a focus in our relationship.

The pattern was repeated many times: my phone would ring on a Monday morning and Dario’s hoarse voice would rasp, ‘I’ve got a client at 11 from out of town. Do you want to come over at 1 and talk about bows?’ More often than not, our conversation would turn to more serious issues.

Both my mother and Dario suffered from Parkinson’s disease as well as cancer and I become an intermediary in sharing information on what drugs seemed to help or make symptoms worse. When I told him of my plans to sell a couple of bows and use the proceeds to present a concert of my mother’s music at Carnegie Recital Hall in honor of her 65th birthday, he asked me to choose which I thought was the best bow of the lot and what I thought the price should be. I had brought the bows only to be appraised and was completely shocked when he called out, ‘Maria, bring me the checkbook. Gabriel has a concert to put on!’

A 1942 violin by D’Attili, labeled, ‘pupil of S.F. Sacconi’. Photos: Robert Bailey, Tarisio

![]()

In the other part of the basement (complete with authentic Tiki bar), I once noticed an unvarnished viola. When I inquired, Dario told me that he had not decided which varnish recipe to use as he was always researching new possibilities. ‘I haven’t made an instrument since 1975. I’ve made between 40 and 50, but you probably won’t see any as most were sold in Cuba, where my wife is from, before the revolution.’ When asked what model he preferred, he brightened up and said ‘Peter of Mantova with Scarampella varnish’. At that moment I made it my quest to find one. My first D’Attili violin was from 1958 and had been played in Havana for 43 years.

When attributing violins, Dario would not force an answer. If a name did not come immediately, in good humor he would turn and ask, ‘What do YOU think?’ I was in the habit of preparing for our meetings by scribbling ideas on a yellow legal pad, and being no expert, I would often posit obscure makers found only in reference books, to which he would reply, jokingly, ‘That was my fourth guess.’

Despite being a prolific certificate writer, he never seemed to be in a hurry to certify an instrument. He was of course not infallible, but he was mystified that there were those who had begun to question his opinion on certain instruments.

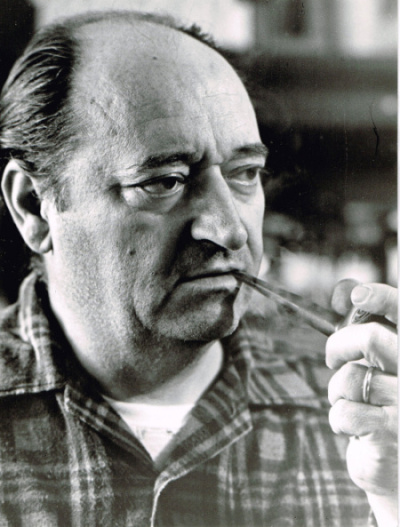

Dario D’Attili in around 1980. Photo courtesy Hans Nebel

By 1992 Dario and Maria were preparing to move to Florida to be near their daughter and her family. My wife was pregnant and Dario was almost as excited about that as I was. Once he moved, I felt the loss of a genuine and inspiring friend. Rather than send violins and bows directly to him, he requested that I first send photos and always include pictures of my daughter, Susannah, who was born that summer. His last letter to me read: ‘All of my certificates begin with “In My Opinion”. I am just one man with one mind and one set of experiences. I am sorry that I don’t see Turin in the photos you sent. I still see Naples, but I don’t know who. I am returning the photos of the violin, but keeping the ones of Susannah.’

D’Attili officially retired in 1997. He never completed his magnum opus, a book on rare Italian violin makers – the ones he had seen but most of us had never heard of – and his great passion for teaching and the establishment of a school for restoration were never realized. He died on April 23, 2004. His keen eye and gentle manner are missed.

Thanks to Hans Nebel, who provided invaluable assistance in preparing this article.

Violinist and educator Gabriel Schaff is author of ‘The Essential Guide to Bows of the Violin Family’.