Why did Eugene Sartory dedicate an exhibition viola bow dated 1931 ‘A Mce Vieux, Estime et reconnaisance’ (‘to Maurice Vieux, esteem and gratitude’)? We can only speculate, but perhaps he was showing gratitude because Maurice Vieux advised his students to choose the best among French bows. Or perhaps it was in honor of what Vieux had brought to the world of the viola – for his role in bringing the instrument to prominence in France is undeniable. Born in 1884, Vieux taught a generation of violists, built up the repertoire for the instrument and, through his own sheer virtuosity and musicality, helped to establish the viola as a solo instrument.

Sartory bow bearing the Vieux inscription. Photo: Tarisio

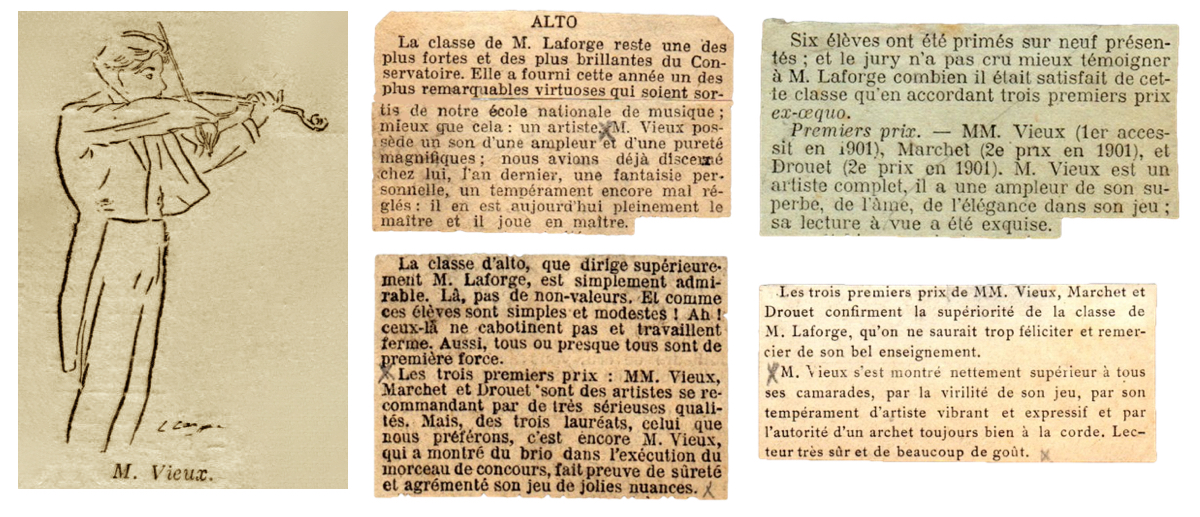

Let’s go back to June 1902 and the competition of the Conservatoire National de Musique de Paris. The music journalists reporting on the performances were lavish in their praise of the 18-year-old violist Maurice Vieux. One wrote: ‘Mr Laforge’s class remains one of the strongest and brightest in the conservatory. It provides this year one of the brightest virtuosos that ever came out of our national music school, and even better than that: an artist. Maurice Vieux has a sound of unparalleled magnificence and purity…’ Another wrote: ‘Maurice Vieux is a complete artist, he not only has a superb and full sound, he also has soul, and elegance in his playing; his sight reading was exquisite…’ Vieux therefore received the honors of the press as well as winning the Premier Prix of the competition.

A sketch of the 18-year-old Vieux and some of the press reviews of his Premier Prix-winning performance in 1902

Vieux began his professional career immediately, in 1903 becoming the first solo viola of the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, where he was to remain until 1921. The best chamber music ensembles solicited him to join them, and in 1905 he performed with the Parent Quartet, the Societé of the Double Quintette, the Joachim Chaigneau Quartet and the Touche Quartet. In 1906, aged 22, he took up the position of soloist at the Paris Opéra, becoming Premier Alto Solo in 1909, where he would remain until reaching the age of retirement in 1949. Meanwhile, he toured all over Europe, visiting the UK, Switzerland, Belgium and Spain in 1913 with the Double Quintette, and Italy in 1914 with the Touche Quartet. Each time, the press reported on his formidable talent.

When war was declared in 1914, Vieux was sent to Verdun on the Western Front. He was fortunately assigned to the Auxiliary Services rather than serving on the front line, but he witnessed the horrors of the war, as his letters testify. In October 1918 Théophile Laforge, his teacher and founder of the first Class of Viola at the Paris Conservatoire, died and when Vieux was demobilized in 1919 he became Professor du Conservatoire in Laforge’s place. Thus began his career teaching a new generation of violists.

‘The interpretation of any work in which [the viola] came into play was entrusted to a second-rate violinist who complacently complied with the need to abandon his favorite instrument to go to the viola’ – Maurice Vieux, 1928

In 1928 Vieux wrote an article entitled Reflections on the technique of the viola, in which he discussed the place of the viola in history. He recalled: ‘The interpretation of any work in which this instrument came into play was entrusted to a second-rate violinist who complacently complied with the need to abandon his favorite instrument to go to the viola.’ As so few viola virtuosos existed, composers considered it the poor relation of the quartet. And consequently, with so few works available for the solo viola, musicians tended to choose a more rewarding instrument.

A postcard of Vieux from 1933

Looking to break this vicious cycle, Vieux commissioned works to be written for the viola. He also composed himself, writing an elegy for piano and violin dedicated to his daughter and a lullaby dedicated to his son. Given the limited means of recording music at the beginning of the 20th century, there are unfortunately very few recordings of Vieux available. He can be heard in the Piano Quartet no. 2 op. 45 by Fauré, recorded in 1940 with Marguerite Long, Jacques Thibaud and Pierre Fournier, just after the news of Germany’s invasion of Holland had reached Paris. Long recalled: ‘Overcoming our mortal fear with that courage that artists so need, we started our recording in an extraordinary atmosphere… Swept up by the music beyond the reach of the present time, we succeeded in the tour de force of recording, without any lapse, the entire Quartet in one day. It was sublime.’ [1] There is also a recording of Vieux playing l’Arioso et Allegro written for him by his friend the Romanian composer Stan Golestan.

‘Overcoming our mortal fear with that courage that artists so need, we started our recording in an extraordinary atmosphere’ – Marguerite Long, 1940

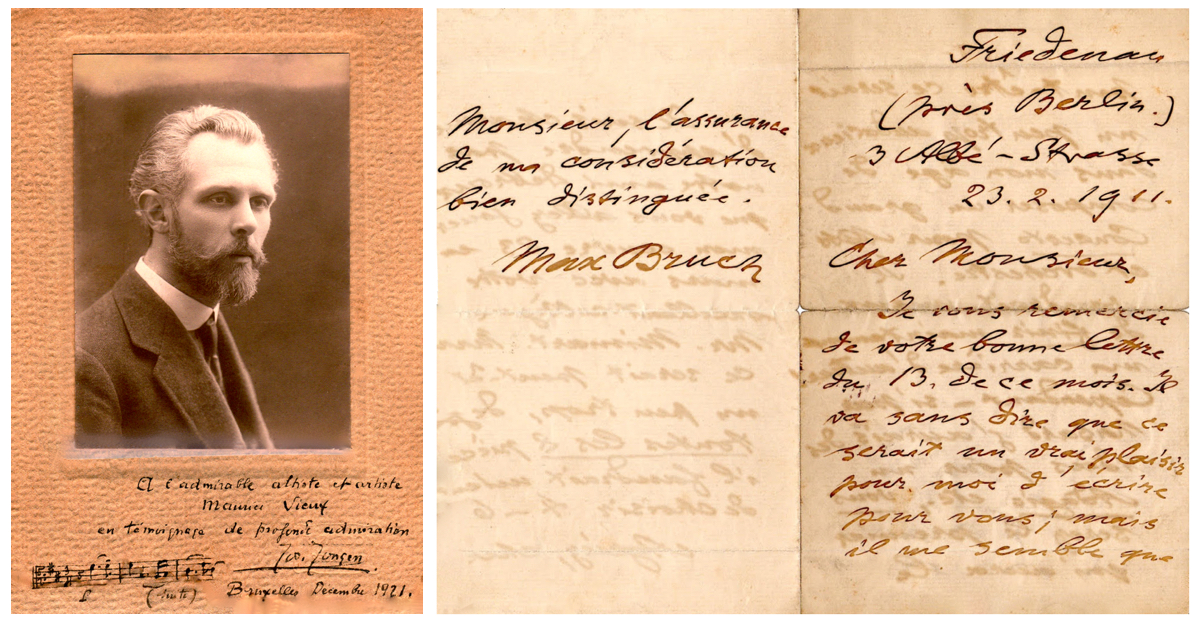

In addition to a full schedule of teaching and playing at the Opéra, Vieux regularly played for contemporary composers such as Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Debussy, Bruch and his close friend Joseph Jongen, many of whom dedicated works to him, such as Bruch’s Romanze for Viola and Orchestra. He was in great demand as a chamber musician and was invited to be part of the ensembles of Ysaÿe, Kreisler, Cortot, Marguerite Long, Enesco, Casals, Caplet and Thibaud. However, when solicited for extensive tours, Vieux invariably answered: ‘What would become of my students?’

A signed photo of composer Joseph Jongen with a dedication to Maurice Vieux (left), and a letter from Max Bruch to Vieux, accepting a commission to write a piece for the viola. Both composers dedicated works to Vieux

Arguably, however, his greatest contribution to the viola was not the expansion of the repertoire but the teaching of top virtuosic violists. Over a hundred of his students obtained the Premier Prix at the Paris Conservatoire, among them Pierre Pasquier of the Pasquier Trio, Etienne Ginot, André Jouvensal (who wrote a tribute to his former teacher in 1951 [2]), Maurice Husson of the Calvet Quartet, Micheline Lemoine, his nephew Jacques Balout, Jean Cauhapé of the Boston Symphony and Serge Collot of the Parrenin Quartet. He also wrote studies for 20 of his Premier Prix students (20 Etudes, published in 1927), all of them notoriously difficult, and deconstructed ten particularly difficult orchestral traits in another volume. [3]

Vieux with his viola class at the Paris Conservatoire in c. 1944. Serge Collot, who won the Premier Prix in 1944, is standing in the second row on the far right

Vieux was not only generous with his students, he also enjoyed lending his services whenever he could. He was involved in several musical associations, participated in charity concerts at the end of World War II, and often played at Sunday Mass at the Eure village church near his country house. He enjoyed fishing and hunting, loved his dogs, and kept canaries and even a parrot as pets. When he later settled in Montmartre in Paris, he had a cat and a poodle. He was an amateur painter and frequently offered supper to the Montmartre artists when they needed it.

Physically Vieux was a force of nature. At 1.75 m he was a tall man and thanks to his legendary sweet tooth he sometimes approached 100 kg

Physically Vieux was a force of nature. At 1.75 m he was a tall man (1.66 m was the average height at the time) and thanks to his legendary sweet tooth (he could consume an entire jar of jam when returning from the Opéra) he sometimes approached 100 kg. Unfortunately this, combined with his impossible schedule of working almost seven days a week apart from short summer vacations, eventually got the better of his health and he developed heart disease, which finally killed him in 1951.

Apart from his military decorations from World War I, Vieux received other official honors, including Officer of the French Legion d’Honneur in 1930; Knight of the Order of Leopold Belgium and Knight of the Order of Nichan-Iftikar of Tunisia in 1932; and Knight of the Order of Cultural Merit of Romania in 1935.

Jean-Claude Vieux is the son of Maurice Vieux. Photos courtesy of the Vieux family.

Text translated by Marie Turini-Viard. Next week, Pierre Guillaume examines the fine Sartory bow dedicated to Maurice Vieux.

Vieux instruments and bows

Tarisio is offering several instruments and bows owned by Maurice Vieux in the October London sale, including:

Lot 30: a rare 1931 exposition viola bow by Eugene Sartory

Lot 42: a viola by Albert Caressa given to him on the occasion of his Premier Prix in 1902

The family of Maurice Vieux wants these historical instruments to live the life for which they were manufactured. Upon request, the family can provide a letter of provenance from Maurice Vieux.

Notes

[1] Marguerite Long At The Piano with Fauré, René Julliard, 1963.

[2] Bulletin no. 16, Paris Conservatoire, July 1951.

[3] Reviewed in vol. 7 of the Journal of the American Viola Society.