In the 19th century there were two important Stradivari cellos in Russia. The first was the 1712 ‘Davidoff’, the cello that Count Vielgorsky gifted to the Russian cellist and composer, Karl Davidoff and is now played by Yo-Yo Ma. The second was the 1709 ‘Markovitch’, a glorious and noble example with provenance dating to the 18th century which was recently sold by Tarisio Private Sales.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Russian nobility was enamored with foreign literature, art and music. Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia for over thirty years, brought scores of influential artists, intellectuals, scientists and musicians to Russia. Chamber music flourished in the palaces and wealthy homes of St. Petersburg and Moscow as leading musicians from Paris, Vienna and Milan were brought in and kept on retainer.

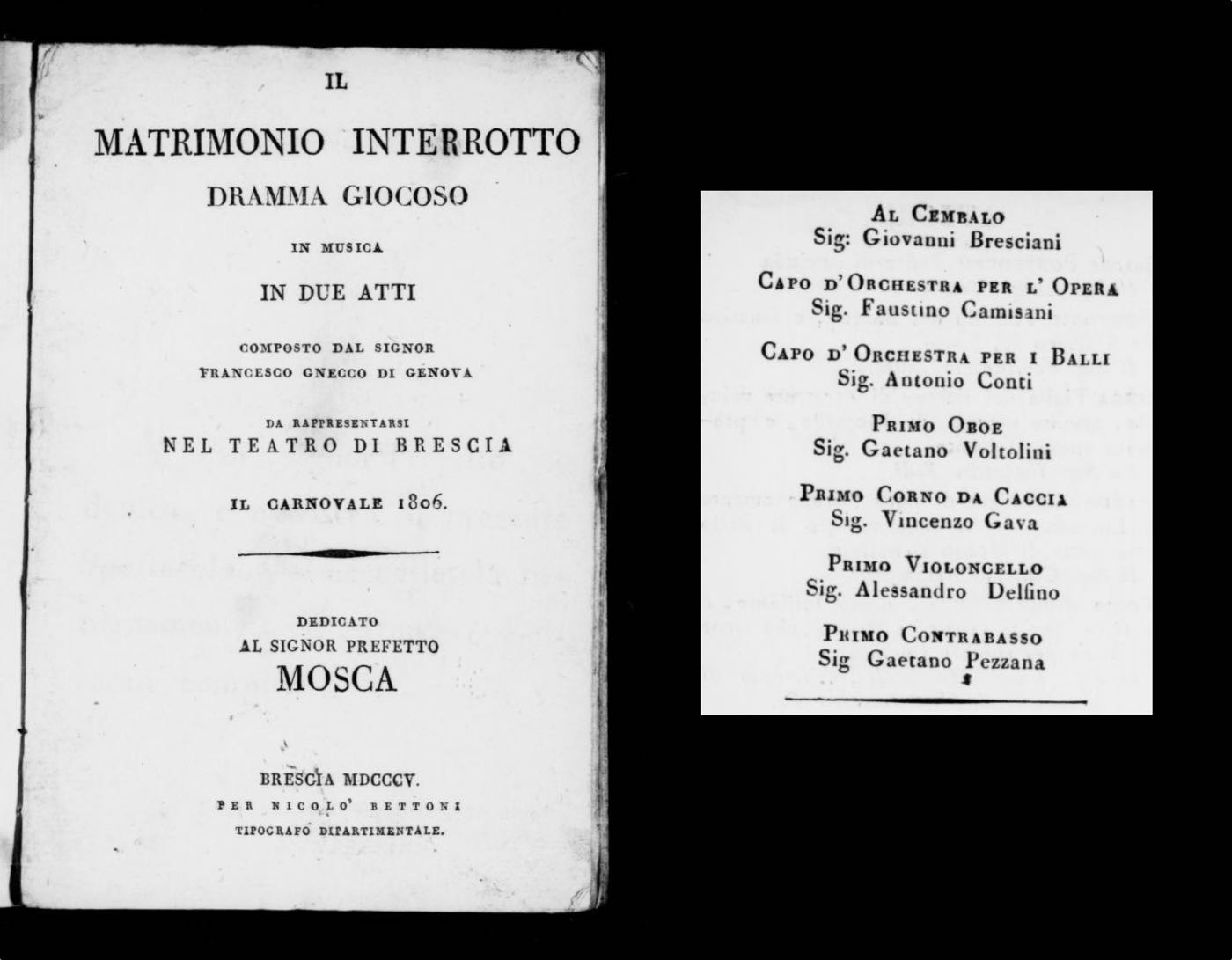

One such artist was Alessandro Delfino, the primo violoncello of La Scala in Milan who came to Russia twice, first in 1793 to enter the service of Catherine the Great in St. Petersburg.[1] Delfino performed for the Russian court and in the Hermitage Theater as part of a string quartet led by the German violinist Ferdinand Titz.[2] Some have said that Delfino was recruited to Russia personally by Grigory Potemkin, the military general and confidant and lover of Catherine the Great.[3] The Empress died in 1796 and shortly thereafter Delfino returned to Italy to advance his career. Between 1804 and 1806 he was again solo cellist in productions at both La Scala and Il Teatro di Brescia.[4]

Delfino was the primo violoncello in the production of Francesco Gnecco’s Il Matrimonio Interrotto which was produced at the Teatro di Brescia in 1806.

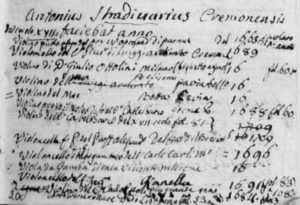

The 1709 Stradivari cello was recorded in the possession of Prof. Alessandro Delfini of Brescia in Count Cozio’s Carteggio in around 1805.

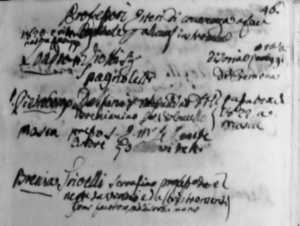

It’s not known when exactly Delfino acquired the cello[5] but it was in his possession by the early years of the 1800s because Count Cozio, the eminent violin collector, cataloged the instrument in his Carteggio in around 1805 noting it was in the possession of “Professor Alessandro Delfino di Brescia”. Ten years later, on June 5th, 1816, Cozio took detailed notes and measurements of the cello. And in 1820, Cozio included Delfino in a list of “Professori Esteri” (teachers living abroad) under “S. Pietroburgo”. After this, there is a note “1822 a Mosca … presso … il Conte Andre Gudovich.” ([in] 1822 to Moscow to Count Andre Gudovich).[6] Explanations differ as to how Gudovich ended up with the cello.[7] My favorite is that he acquired the Stradivari “in exchange for a superb open carriage with four jet-black horses, as well as two bondsmen, a coachman, a footman, and all their families.[8]

Count Cozio’s list of Professori Esteri (teachers abroad) in 1820: Viotti and Spagnoletti in London and Delfino in St. Petersburg. It appears that in 1822, Delfino (and/or the cello) moved to Moscow “presso … il Conte Andre Gudovich” (to, or into the service of Count Andre Gudovich).

According to one version, Gudovich acquired the Stradivari “in exchange for a superb open carriage with four jet-black horses, as well as two bondsmen, a coachman, a footman, and all their families.”

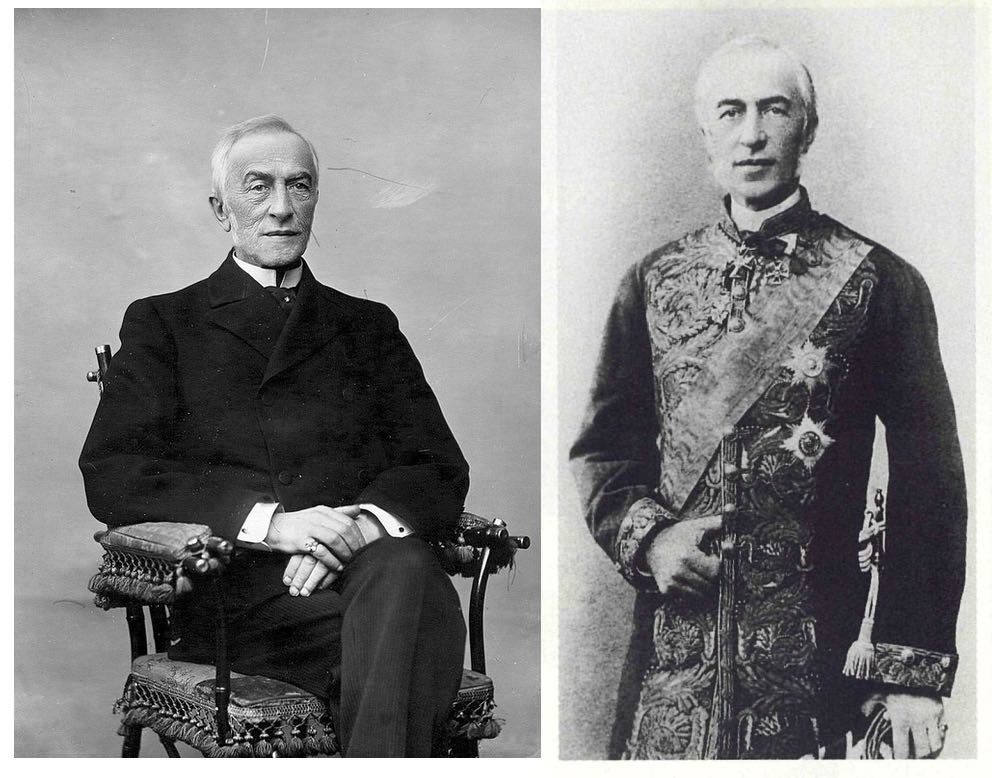

Andrei Ivanovich Gudovich (1781/2-1869) by George Dow, c. 1820-25. St. Petersburg: The State Hermitage.

Gudovitch was a military officer during the French invasion of Russia in 1812; owned large amounts of land; had over 5,000 serfs; and is remembered as an aristocratic dilettante cellist.[9] Having no male heirs of his own, in 1863 he gifted the Stradivari to his grand-nephew, Andrei Nikolayevich Markovitch. By profession, Markovitch was a lawyer, a state secretary and a Russian Senator. In his private life he was an amateur cellist and part of an influential circle that contributed greatly to the development of western musical culture and pedagogy in Russia. Perhaps his most lasting contribution was as co-founder of the Russian Musical Society which, together with the pianist Anton Rubinstein, established the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

Senator Andrei Nikolayevich Markovitch (1830 – 1907)

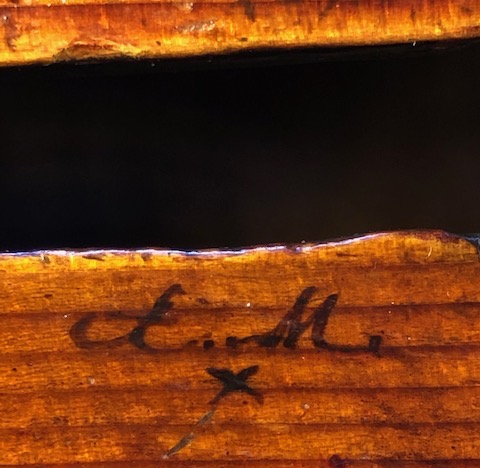

A small inscription at the outer edge of the cello’s bass soundhole is thought to be the Senator’s initials, “A M” (or “S M”).

The preeminent English dealers W. E. Hill and Sons knew the ‘Markevitch’ cello and mentioned it in their 1902 monograph on Stradivari. In fact, Alfred Hill personally inspected the cello when he and Baron Knoop traveled to Russia and visited Markevitch in 1899.[10]

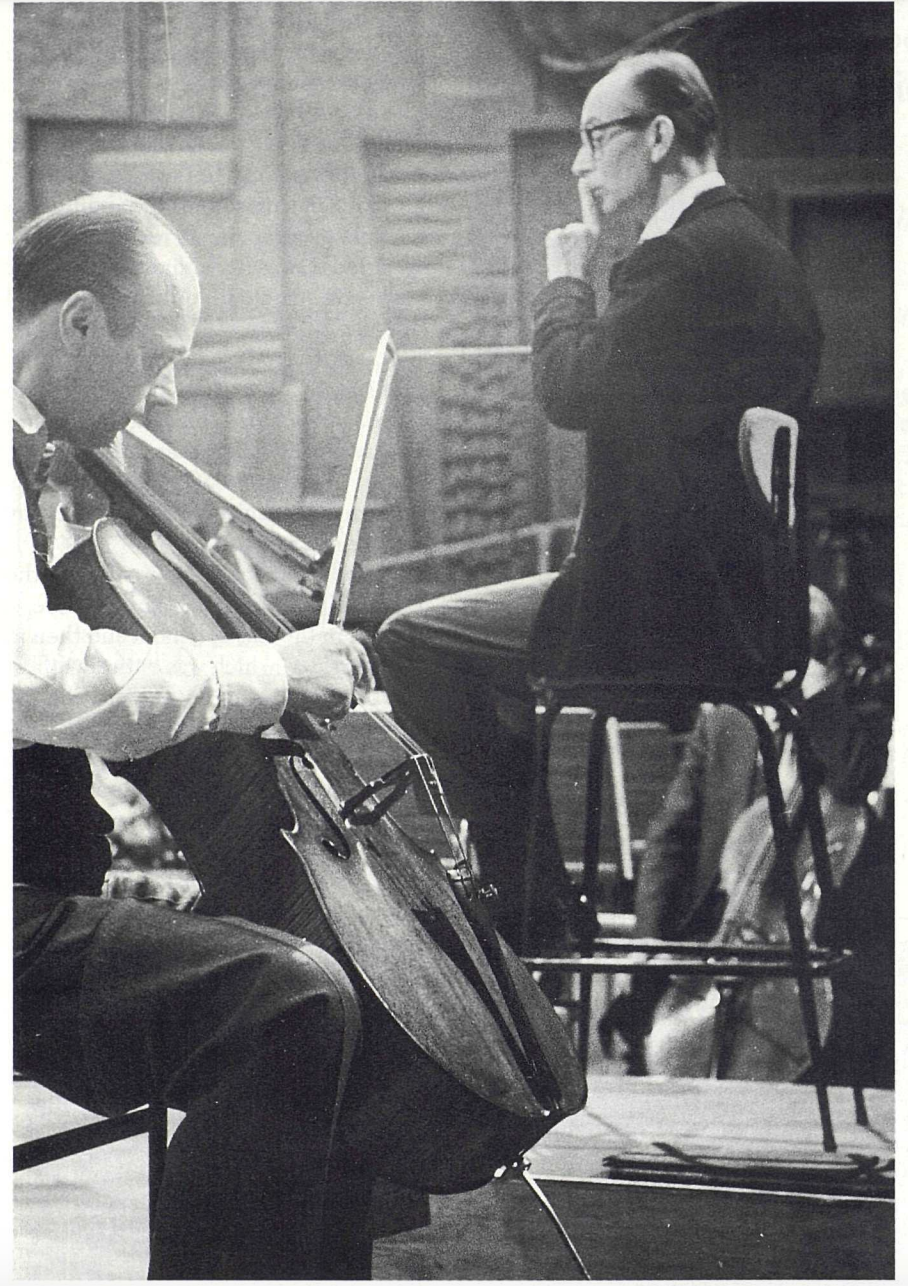

High society chamber music in Russia in c. 1900. Senator Markevitch (cello), Leopold Auer (violin). At the far left is Boris Markevitch, nephew of the Senator and father of Dimitry Markovitch.

Senator Markevitch was part of a musical family. His father was a musician, historian and poet. His nephew Boris was a pianist, and his grand-nephews, Igor and Dimitry Markevitch, would both become gifted and successful musicians, the first a composer and conductor and the second an accomplished cellist. Senator Markevitch died in 1907, and the Stradivari passed to his son Nikolai, who sold it in Paris in 1915.[11]

It took three months for the cello to arrive from St. Petersburg; it traveled via Finland, Norway and England before finally arriving in France in 1915.[12] Caressa & Français had arranged to purchase the Stradivari for 31,000 francs.[13] Three months later they sold it to Monsieur Rateau of Paris.[14][15]

In 1933 the cello came back to Caressa and this time was sold to the Parisian banker Jean-Louis Courvoisier.[16][17] A few years later the cello was in Los Angeles, in the possession of Grace Broadbent who had acquired it from the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company.[18] Mrs. Broadbent and her husband had purchased at least two other cellos from the Wurlitzer firm: a Matteo Goffriller (41041) in 1937 and the 1698 ‘Marquis de Cholmondeley’ Stradivari (41455) in 1943.

By 1959 the cello was in the collection of a Dallas paint and varnish merchant named Clarence Dragert who also owned the ‘Lord Nelson’ Stradivari violin. Dragert and his wife Lucile were boosters of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and purchased the ‘Markevitch’ to lend it to Lev Aronson, its principal cellist.[19] Aronson had immigrated from Latvia in 1948; several years earlier, his Amati cello had been confiscated by the occupying Germans forces. Newly arrived in America, he took a job with the Dallas Symphony and quickly became its principal cellist, a position he held until 1967. Aronson was an influential teacher and mentor to a generation of American cellists including Lynn Harrell and Ralph Kirshbaum, and he would go on to play the ‘Markevitch’ for several seasons until Dragert took it back.[20]

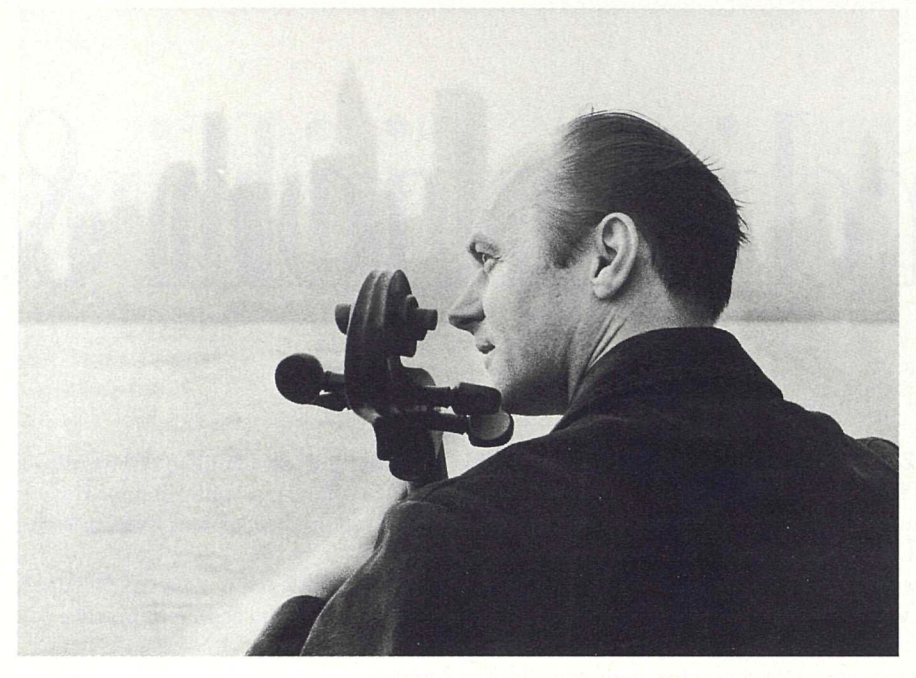

Lev Aronson (1912-1988).

In 1962 something special occurred – an almost unprecedented event in the history of Stradivari instruments. The ‘Markevitch’ cello, which had been sold by the Gudovitch-Markevitch family in 1915, was repurchased by a descendant nearly 50 years later.

Dimitry Markevitch was born in La Tour De Peilz near Montreux, Switzerland in 1923. He never knew his great-uncle, the Russian Senator, nor his father Boris, the pianist who had died of tuberculosis just days after Dimitry was born. But music ran in his blood. His older brother Igor became an avant-garde conductor and composer, and Dimitry took up the cello. He studied with Maurice Eisenberg in Paris and called himself “the first disciple of Gregor Piatigorsky.”[21] His Wigmore Hall debut in 1949 received glowing reviews in both The Strad and Violins & Violinists.[22] He moved to America in the 1950s and joined the New York Philharmonic in 1958.

Dimitry Markevitch in New York in the 1950s.

In 1962, with his career going strong, he was able to re-purchase his great-uncle’s cello. Two years later, playing his newly acquired Stradivari, Markevitch gave a recital at Wigmore Hall whichThe Strad magazine reviewed jointly alongside a concert by Rostropovich, introducing them as “two exceptionally interesting cello concerts in London.”[23] Markevitch was an astute musical historian who championed historically informed performances. He published a critically acclaimed edition of Bach suites and made the first recording of the Kodály Solo Sonata op 8. His book Cello Story is a personal memoir in the guise of an informative historical overview of the instrument.

Back in the family: Igor Markevitch conducts Dimitry Markevitch with the ‘Markevitch’ in 1967 in Paris.

But by the end of the 1960s, Markevitch had grown tired of New York and missed the culture of Europe, recalls Markevitch’s daughter Elizabeth, an art historian and entrepreneur living in Berlin.[24] In the winter of 1971, he and his family moved to Montreux, Switzerland, not far from where Dmitry was born.

Shortly after they had settled into their new home on the shores of Lake Geneva, tragedy struck. Markevitch slipped on ice and shattered his femur. He spent the next eight months in and out of hospitals, unable to work and in great pain.[25] Prior to the move, Markevitch had planned many months of concert engagements across Europe, which he now had to cancel and pay a forfeit for when he was unable to perform. As debts mounted, Markevitch was forced to consider selling the Stradivari.

Markevitch’s neighbor in Switzerland was David Josefowitz, a chemist, violinist, entrepreneur and philanthropist. The two were almost the same age and had similar backgrounds. Born to parents who left Russia at the time of the revolution, Josefowitz had studied in America at MIT. Josefowitz and his brother Sam were involved in the early manufacturing of Long-Play vinyl records and founded a mail-order subscription service for classical LPs. In the 1950s, Josefowitz returned to Europe and began to collect art and violins. When his friend Dimitry suffered the accident, Josefowitz offered to purchase the Stradivari.

For the last fifty years the ‘Markevitch’ has been owned by a foundation that Josefowitz established, and over the five decades, it has been loaned to talented students and faculty at the Royal Academy of Music in London. In July of this year the ‘Markevitch’ was sold by Tarisio Private Sales.

Dimitry Markevitch on the Champs Elysées in 1966. Photograph: Alain Dejean.

Notes:

1. Brown, M. H., Findeizen, N., History of Music in Russia from Antiquity to 1800, Volume 2: The Eighteenth Century (United States: Indiana University Press 2008).

2. Delfino’s fellow musicians at court included the Czech harpsichord player Arnošt Vančura, the French harpist Jean-Baptiste Cardon and the German clarinet virtuoso Joseph Beer.

3. The Violin Times. no.57. July, 1898.

4. In 1804 Teseo in Milano, in 1804 Nino in Brescia, in 1805 Il Matrimonio Interrotto in Milano, in 1806 Il Matrimonio in Brescia.

5. According to an article in The Violin Times in 1898, the young Delfino was given the Stradivari by his grandfather who had found it among the contents of a house he purchased in Cremona in the 1710s. This is a thrilling tale, but highly implausible.

6. In Cozio’s Proprietari di strumenti che vivono all’estero (instrument owners living abroad) he notes that in 1822 the cello was in Moscow with il Conte André Goudovich.

7. According to the 1898 Violin Times, Delfino had married and fathered a daughter in his earlier trip to Russia and upon his death he left the cello to Count Gudovitch who refused it as a gift and instead purchased it for 20,000 francs from Delfino’s daughter.

8. Dimitry Markevitch, Cello Story, trans. by Florence W. Seder (Princeton: Summy Birchard. 1984), 39.

9. Klaus Grunke, Josef P. Gabriel, and Yung Chin, The Bows of Nikolai Kittel (Cologne: Darling Publications, 2011), 261

10. Letter from Alfred Hill. November 22, 1938.

11. Other histories have mistakenly claimed that Markevitch sold the cello directly to Caressa in 1915, but he died on March 11, 1907 in Saint Petersburg.

12. Caressa records the cello’s extraordinary journey from St. Petersburg to Paris passing through Tornio, Finland; Trondheim, Norway; Hull, England; and Dunkerque, France.

13. “The Jacques Francais Rare Violins Inc. Business Records (1845-1938),” Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Archives Center, Box 55, folders 2 and 4, p. 203

14. Little is known about Rateau. But in 1916 he bought from Caressa an F. N. Voirin cello bow for 1,000 francs and an ex-Piatti Tourte cello bow for 2,500 francs.

15. To disguise the prices they paid and received, the firm used a cipher in their Sales Ledger. The ledger notes that they bought the ‘Markevich’ for rhxzx and sold it three months later for hxzxzx; the code word is harmonieux.

16. Manfred Pohl, Handbook on the History of European Banks (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 1994), 227.

17. http://histoire-vesinet.org/ch-courvoisier.htm

18. Violins & Violinists, December, 1945, p. 52.

19. Frances Padorr Brent, The lost cellos of Lev Aronson (New York: Atlas & Co 2009), 191.

20. Ibid.

21. The Strad, December, 1979. p. 576.

22. The Strad, August, 1949. p 100. and Violins & Violinists, August-September, 1949. p 231.

23. The Strad, February, 1964. p 357.

24. Conversation with Elizabeth Markevitch, June 5, 2022.

25. Ibid.

References:

Baron, John, Intimate Music: A History of the Idea of Chamber Music, Pendragon Press, 1998.

Biddulph, Peter, Chaudière, Frédéric & Dilworth, John, Antonio Stradivari – Catalogue of the 2008 Exhibit in Montpelier, Montpelier, Musée Fabre / Actes Sud, 2008.

Brown, M. H., Findeizen, N., History of Music in Russia from Antiquity to 1800, Volume 2: The Eighteenth Century, Indiana University Press, 2008.

Brendt, Frances Padorr, The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson, New York : Atlas & Co 2009.

Frazier, Brandon, Memoirs of a Violin Collector, Gateway Press, Baltimore, 2007.

Grunke, Klaus, Gabriel, Josef P. & Chin, Yung, The Bows of Nikolai Kittel, Cologne, Darling Publications, 2011.

Hill, William Henry; Hill, Arthur Frederick; Hill, Alfred Ebsworth, Antonio Stradivari. His Life and Work (1644–1737), W.E. Hill & Sons, London, 1902.

Kogan, Oleg, “Young Guns”, The Strad, September, 1996.

Rattray, David, Masterpieces of Italian Violin Making, Balafon Books, London, 2000.

Rattray, David. “Markevitch cello, 1709”, The Strad, March, 1996

Reeves, W, “A Valuable Violoncello”, The Violin Times, No. 57 Vol V, London, 1898.

Rooney, Dennis, “Mastering Bach”, The Strad, April, 1999.

Sackman, Nicholas. “Paganini’s instrument legacy …”, 2021.

Seaman, Gerald, “Amateur Music-Making in Russia”, Music & Letters, Vol. 47, No. 3, OUP, 1966.

The Strad, Concert Reviews, August, 1949.

The Telegraph, “David Josefovitz, music entrepreneur – obituary”, 16 April 2015.

Violins & Violinists, August-September, 1949.