Henri Français was born in Mirecourt in 1861 and descended from an ancient family of stringed instrument makers and lace makers from the Lorraine region. He started his apprenticeship in the workshop of Auguste Darte and moved to Paris in 1880, where he was hired by Gand & Bernardel Frères (see part 4). In this shop, he quickly applied his skills to new making and restoration. After the death of Charles Eugène Gand in 1892, Français was promoted to foreman of the workshop. He went on to win two gold medals, one in the 1897 Brussels Exhibition and another one in the 1900 Paris Exhibition. All this made him highly qualified to take over the succession from Gustave Bernardel, who by 1900 was planning his retirement.

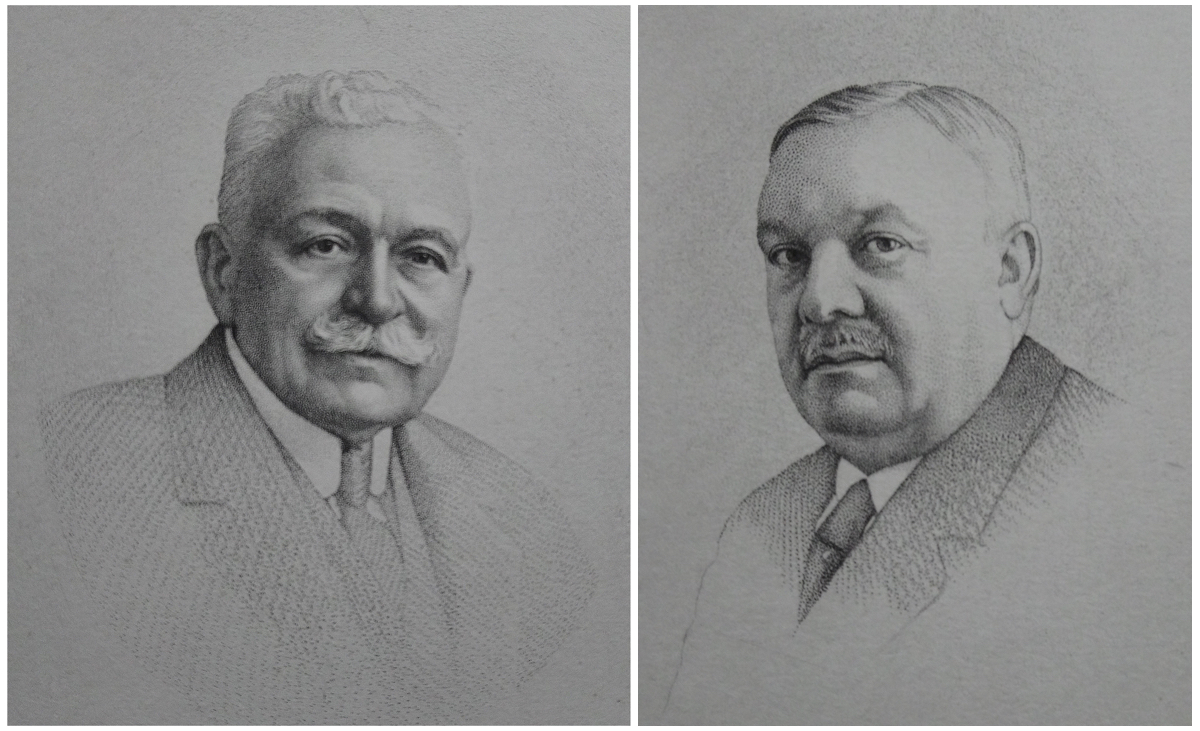

Although very different in character, Henri Français (left) and Albert Caressa had complementary skills that proved highly effective for their partnership. Photos: courtesy Gael Francais

Albert Caressa could not have been more of a contrast in character. Of Florentine descent and born in Nice in 1866, he came to the violin world from a completely different background. At an early age he enlisted in the French Navy and sailed around the world before settling in Paris. [1] It is not clear how he came to be interested in musical instruments, but perhaps his flamboyant personality was attracted by the glamorous world in which collectors and virtuosos competed for fame. A good instinct for business and a strong interest in the field of expertise led him to begin collecting musical instruments. Bernardel, who knew him socially, perceived that he had the qualities to become an excellent manager and decided to hire him. Caressa went on to become director of the business in 1898.

Maison Caressa & Francais (1901–20)

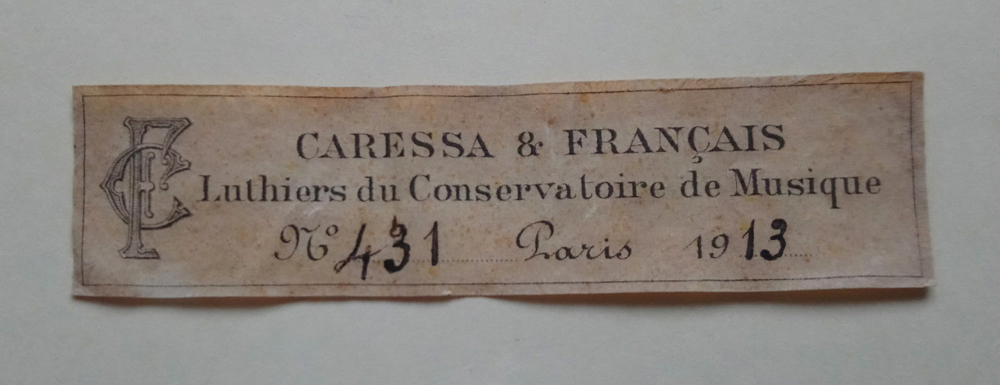

Having found the perfect new partners to take on his business, Bernardel wrote on June 15, 1901, to the Director of the Conservatoire de Musique to announce the new business association of Caressa & Français. [2] He also requested that the crucial function of Luthier du Conservatoire, which all his predecessors had held since Nicolas Lupot, be continued.

Henri Français (left) and Albert Caressa ran the Parisian business together from 1901 until Français retired in 1920. Photos: courtesy Gael Francais

The new business association was officially in place on July 1, 1901, and the Bernardel clientele was informed of it in various music newspapers, including the Monde Musical. Not long after, Caressa & Français was highly praised in a 1905 edition of the magazine Musica by concert artists such as Pablo de Sarasate, Eugene Ysaÿe and Jacques Thibaud. These virtuosos became faithful clients of Caressa & Français as well as good friends. The success of the Caressa & Français business is underlined by the Violin Iconography of Antonio Stradivarius by Herbert Goodkind, in which as many as 47 Stradivari instruments are listed as having passed through their hands.

Caressa & Francais label dated 1913. Photo: courtesy Gael Francais

To understand the place of Caressa & Français in the music world, one needs to observe the importance of music in the daily life of the French Bourgeoisie in the early 20th century. Orchestras and ensembles of all sizes flourished; there was hardly a public establishment (hotel, restaurant, tea room and so on) that did not offer musical entertainment. To fulfil this demand, Caressa & Français employed up to 15 craftsmen for new making, as well as repair and restoration. Among these were fine violin makers such as Emile Laurent and Emile Boulangeot and fine bow makers such as Victor and Jules Fetique. The firm also produced handmade strings and the famous ‘Gustave Bernardel’ rosins.

In 1913 the shop was transferred from the Bernardel address at Passage Saulnier to a new location in rue de Madrid, next to the Paris Conservatoire de Musique.

Maison Albert Caressa (1920–38)

In 1920 Henri Français retired and Albert Caressa continued running the company for another 18 years. The mode of operation remained the same, since most of the business had been essentially in the hands of Caressa. Français’s role had been more of a traditional artisan in charge of all workshop activities.

Albert Caressa’s label, which he used between 1920–38. Photo: courtesy Gael Francais

As the dark clouds of World War II appeared on the horizon, Caressa turned to the US for business opportunities in 1937. He knew most of the important American violin dealers and increased his business activities with some of them, presumably as a financial security for what was to come in Europe. [3] The most important of these were Emil Herrmann of New York, and Erich Lachman and A. Koodlach, both of Los Angeles. During his career Caressa had assembled one of the most important and rare collections of stringed instruments and bows in the world. As the US economy was not yet affected by World War II, violin dealers there were extremely interested in dealing with him.

However, all business transactions were cut short by Caressa’s sudden death on February 17, 1939, at his luxurious villa at Cap Ferrat, in the south of France. Fortunately, he had prepared his succession a year earlier, choosing his son-in-law, Emile Français, to take over the business.

Maison Emile Français (1938–84)

Emile Français was born in Paris in 1894. He apprenticed with his father, Henri, and from 1911 to 1913 worked in the Penzel shop in Markneukirchen. In this town he met Jay C. Freeman, head of the violin department of Lyon & Healy, who convinced him to join this important firm in Chicago. There Emile was trained in restoration under Emile Laurent, the former foreman of the Caressa & Français establishment.

When World War I broke out, he returned to France to serve his country but suffered a serious head injury that left him incapacitated for over a year. In 1919 he married Caressa’s daughter, Lucile, and resumed his training under other foremen, including Arthur Papot and Jules Fétique. In 1920 Emile replaced his father in the shop, became himself foreman and assisted his father-in-law with the business operation of the firm.

Emile Francais (left) and Yehudi Menuhin comparing his copy of Menuhin’s ‘Prince Khevenhueller’ Stradivari violin with the original. Photo: courtesy Gael Francais

When Caressa retired to his villa in the south of France in 1938, Emile was left alone to manage the important succession of the Maison founded by Nicolas Lupot. He received, as had his predecessors, the title of Luthier du Conservatoire National de Musique. He is known for his beautiful replicas, for example of the 1733 ‘Khevenhueller’ Stradivari commissioned by Yehudi Menuhin (pictured below) and of the ‘Ysaÿe’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’.

Emile Français’s copy of Menuhin’s 1733 Stradivari violin, the ‘Prince Khevenhueller’. Photos: Tarisio

Emile Français’s shop, like those of his predecessors, attracted the most famous concert artists. Emile left in Paris a powerful imprint. He was the last official successor of the Maison of Nicolas Lupot. The impressive collection of instruments and bows that he left after his death was probably one of the most important collections of the 20th century.

Emile Francais (far right) at the French Nationale Académie de Musique (FNAM) examining a violin presented to him by Henri Rabaut, Director of the FNAM (center), and Jacques Chauyet, its Secretary General (left). Photo: courtesy Gael Francais

Emile had two sons: Jean, who followed a diplomatic career, and Jacques, who was destined to take over the succession in Paris. However, destiny decided otherwise. After almost two centuries, this renowned Parisian house sadly closed its doors in 1981 when Emile retired, and the shop’s fittings along with its wood collection were sold by Sotheby’s the following year. Emile died a few years later, in 1984. However, the famous Parisian house did not quite die with him. Although the line of succession in Paris had been severed both officially and geographically, it was reborn under the Français name in the New World, when in 1951 Jacques Francais opened his business in New York. He was to become one of the most important 20th-century dealers of musical instruments in the US.

In conclusion, one can observe that official functions and honorary titles were of the utmost importance for Nicolas Lupot and his successors. Gaining prestige was the key to a successful enterprise. The only competitor who also followed this path for a short while was Gabriel Thibout, who was the official violin maker of King Louis-Philippe. Having an official title helped Lupot to secure the famous 1820 order of 29 instruments bearing the Royal Coat of Arms for the Chapelle of Louis XVIII, and similarly in 1878 when Gand & Bernardel Frères received the impressive order from the French government of 86 instruments for the Trocadero Palace.

The other significant fact was that all the successors of Lupot were able to maintain the official connection with the Paris Conservatoire de Musique, from 1830 with the Maison of Charles François Gand until the closing of the Maison of Emile Français in 1981 – an impressive 151 years. It is remarkable that all the political upheavals that occurred since the creation of the Conservatoire de Musique in 1795 did not truly affect the transmission of the official function and title associated with it.

Gael Francais is Jacques Francais’s nephew, Emile Français’s grandson and Henri Français’s and Albert Caressa’s great-grandson. He is the last descendent of one of the most ancient lines of instrument makers in France, going back to 1612.

Notes

[1] Français Gael, ‘The Français House of Violin making, A Retrospective’, Part I, Journal of the Violin Society of America, Vol. XIX, No.3, 2005.

[2] Before the association with Français became reality, Caressa had contemplated a different scenario. He wanted to create a new association with Paul Serdet, which would succeed Gustave Bernardel. Serdet was a violin maker with a solid reputation, having worked in the shop of Hippolyte Chretien in Lyon. His association would be beneficial to Caressa’s business ambitions, particularly as Serdet would bring substantial capital to the new enterprise to help buy out Bernardel’s business. However, the idea fell through, probably because Bernardel disliked the idea of introducing someone new to the firm. His strong preference was for Henri Français, who had been the head of his workshop for 21 years and who was his most trusted associate. Français’s financial contribution was more modest, which is understandable given he never had a business of his own. This left Caressa, as the firm’s commercial director, to carry most of the financial burden of the succession. Bernardel was very pleased with this outcome.

[3] Correspondence between Albert Caressa and US dealers 1937–38, Francais, Gael, personal archives.