Throughout history spectacular events occur and special individuals emerge to make an indelible mark. Nicolas Lupot (1796–1824) is one of these personalities. He marked the history of French violin making in a profound way and remains the most venerated violin maker France has ever had. As we will see, all of his successors strived to emulate his skills and stay true to his impeccable reputation. This series will focus on the odyssey of Lupot’s line of succession, which spanned over almost two centuries and comprised ten Maisons de Lutherie (houses of violin making). [1] It will not address the many talents of Lupot’s craftsmanship, which have been well documented elsewhere, [2] but will focus instead on the political situation to which each Maison had to adapt; first during the upheavals of three consecutive revolutions; then during the multiple attempts to restore the French monarchy; and finally during the Industrial Revolution.

Particular attention will be given to the official roles that were established for the maintenance of the instruments of the King’s Orchestra and to which the most talented violin makers of the period were appointed. These official functions continued under successive governments, and each Maison until the end of the Second Empire in 1870 had to struggle either to maintain or to regain them when they were eliminated by a new political regime. Throughout history artists and artisans have sought the support of the aristocracy and, later, of the haute bourgeoisie (upper middle class) to promote their work. The family of Lupot was no exception. Nicolas Lupot’s father, François, had the fortune to be appointed Violin Maker of the Court of Wuertemberg in Stuttgart. We will see that obtaining official functions, and the honorary titles associated with them, became of great importance to Nicolas Lupot and all his successors. The labels found in their surviving instruments provide a window on to the political changes to which they had to adapt. They show changes of address, the loss or restitution of a title, or the gain of a new official function with the corresponding title.

Maison Lupot (1796–1824)

The odyssey began in the midst of very turbulent times: the French Revolution of 1789, the proclamation of the First Republic in 1792 and the execution of Louis XVI the following year. Nicolas Lupot was born in Stuttgart in 1758. The Lupot family moved to Orleans in 1769 where Laurent Lupot, Nicolas’s grandfather, had been established as violin maker since 1756. Nicolas started working with his father in Orleans and made his first violin bearing his own label in 1774. He opened his own shop in 1782.

Nicolas Lupot engraving. Photo: courtesy Gael Francais

The provincial town of Orleans offered Lupot a calm atmosphere to improve his craftsmanship. This is the period when he started working for François-Louis Pique, who was well established in Paris. Pique and Lupot happened to share a common client who lived in Orleans. Pique, being overloaded with work, sought the help of Lupot, whose talents were already beginning to be appreciated. However, the political troubles of the Revolution were looming and after 1789 many aristocrats and bourgeois fled, taking refuge abroad. The next years were marked by considerable political unrest, known as La Terreur, and by the execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in 1793.

It appears that Lupot tried to stay out of politics as much as possible and was probably reluctant to adapt to the new regime

The Revolution was for violin makers, as well as artisans in general, a difficult period, as they all had to adapt to the new political situation. Some had held official functions under the old regime, including Leopold Renaudin who had been in charge of the maintenance of the instruments of the orchestra of the Académie Royale de Musique in Paris. Although Renaudin embraced the new regime with conviction, events turned against him and he ended up being executed in 1795 by the very people he had supported. Many executions and arrests followed, and in 1795 even Lupot ended up behind bars for several months (the exact reason for his arrest is not known). After his release, Lupot decided to move to Paris to seek a better future. It appears that Lupot tried to stay out of politics as much as possible and was probably reluctant to adapt to the new regime. The king and the aristocracy had always supported the arts, and violin makers, known as Luthiers d’Art (artisans of the art), were an integral part of that world.

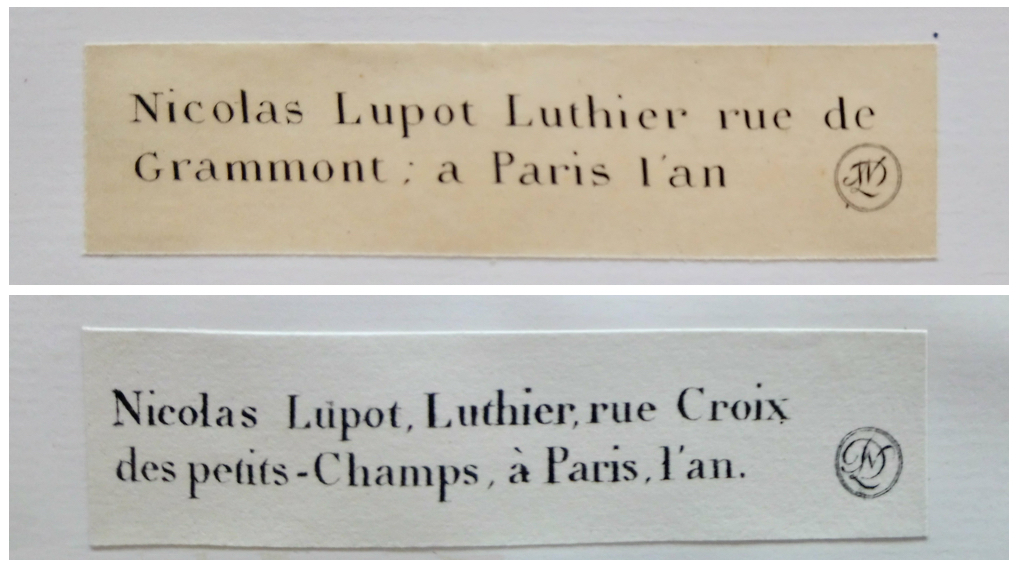

Lupot’s labels from his period at rue de Grammont, 1796–98, and at rue Croix des Petits-Champs, 1806–15. Photos: courtesy Gael Francais

From 1796 until Lupot’s passing in 1824, five types of labels from his Paris period are known. The first printed labels are from the 1796 to 1798 period at rue de Grammont. This corresponds to the Directoire government of 1795–99, which was a period of public disturbances and political unrest with coups d’état from both the royalists and the Jacobins. Lupot had just moved to Paris and probably tried to remain neutral. (One rare handwritten label dated ‘L’an 6 de la Republique Francaise’ was placed in a violin made for Charles Sauvageot, the first laureate of the French Conservatory of Music to be awarded the First Prize.)

From the time Lupot settled in Paris in 1796 until 1815 there is no mention in his labels of an official function or of a title

Lupot’s printed labels from 1798 to 1805 still mention the rue de Grammont address. On November 9, 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew the Directoire and set up the Consulat (1799–1804). On December 2, 1804, the Empire was founded for the first time (1804–14), Napoleon became Emperor of France and re-established the absolute monarchy. The printed labels from 1806 to 1815 show the second shop address of Lupot at rue de Croix des Petits-Champs.

From the time Lupot settled in Paris in 1796 until 1815 there is no mention in his labels of an official function or of a title. This is despite the fact that at the end of the year 1813 he received from Napoleon the honorary function and title of Luthier de la Chapelle de Sa Majesté l’Empereur et Roi. Lupot had just started his service for the Emperor when on January 2, 1814, France was invaded by a coalition of European countries. Napoleon was defeated in battle, followed by his abdication in April and exile to the Italian Island of Elba.

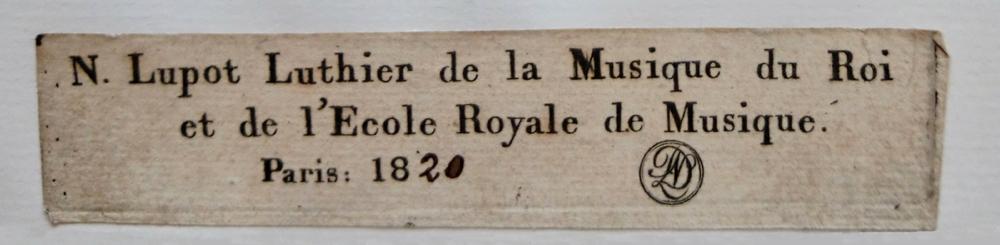

Lupot’s labels from his last period, 1815–24, mention his honorary title. Photo: courtesy Gael Francais

Finally the printed labels of Lupot’s last period from 1815 to 1824 mention his new honorary title, ‘N. Lupot, Luthier de la Musique du Roi et de l’Ecole Royale de Musique’ (Violin Maker of the Music of the King and of the Royal School of Music), awarded after the Bourbon Restoration in 1815 (while the title had changed, the underlying function remained the same). This period saw two Bourbon kings accede to the throne: Louis XVIII in 1815 and Charles X in 1824. There was also an interim period called Les Cents-Jours (The Hundred Days) from March 20–June 20, 1815, which represented an attempt by Napoleon Bonaparte to regain power. He was defeated once again by the European coalition at the Battle of Waterloo and deported for the rest of his life to the British Island of Sainte-Helene.

The period between 1815 and 1824 corresponds in my opinion to the most beautiful instruments made by Lupot. In 1820 he was fortunate enough to be asked to reorganize the Chapelle of King Louis XVIII (the Music Ensemble of the King) and received the largest order of instruments in his career, consisting of 14 violins, five violas, six cellos and four double basses. We know that Lupot was able to make one string quartet in 1820, and he wrote later that in 1824 he will be able to deliver 12 more violins. [3] Unfortunately Lupot was not able to finish the order, which was completed after his death in 1824 by his pupil and successor, Charles François Gand.

Lupot remains one of the finest and most inspirational French violin makers. His instruments are exceptional in terms of craftsmanship and sound. His clientele included renowned concert artists such as Pierre Baillot and François Habeneck, rich amateurs from the haute bourgeoisie, as well as collectors who admired his qualities as craftsman, his skills in restoration, and his integrity as an expert and a merchant. As Luthier de la Musique du Roi et de l’Ecole Royale de Musique from 1815 he was an integral part of the sovereign’s court and specifically part of the Menus Plaisirs et Affaires de la Chambre – a name describing the function of an administration, which can be translated as the Amusements and the Matters of the Chamber. After the 1789 Revolution the statute of the Menus Plaisirs du Roi was abolished, but it was restored during the First Republic under a different name and designed not for the pleasure of a sovereign but for large popular events. Under the Empire, the Menus Plaisirs were once more renamed in 1806: la Chapelle et la Chambre de l’Empereur et Roi. [4]

Part 2 examines the Maison of Lupot’s pupil and successor, Charles François Gand.

Gael Francais is Jacques Francais’s nephew, Emile Français’s grandson and Henri Français’s and Albert Caressa’s great-grandson. He is the last descendant of one of the most ancient lines of instrument makers in France, going back to 1612.

Notes

[1] Most of the historical facts in this series were gathered from the remarkable book by Sylvette Milliot, Nicolas Lupot, Ses contemporains et ses successeurs. Other historical accounts were selected from the personal archives transmitted by the successors of Lupot to the Francais family. From all the archives inherited from the successors of Lupot, one tranche including the books called Signalements was donated in 1981 by the Francais family and a second tranche, composed of rare original documents and letters from clients of the Gand shop was donated in 2018 by Gael Francais to the Musée de la Musique in Paris.

[2] ALADFI, Nicolas Lupot, l’âge d’or de la lutherie française, 2018.

[3] Milliot, Sylvette, Nicolas Lupot, Ses contemporains et successeurs, vol. I, pp.75 & 80, Messygny-et-Vantoux: JBM Impressions, 2015.

[4] Ibid, vol. I, pp.61–62.