The recent discovery and return of the stolen 1734 ‘Ames, Totenberg’ Stradivari violin, missing for 35 years, raises important questions about how best to increase the odds of recovering a stolen instrument. The roster of stolen violins is long and the trail to many of these instruments has unfortunately gone cold. But there have also been noteworthy recoveries besides the ‘Ames, Totenberg’. These bring into sharp focus the need for due diligence and its impact on potential outcomes: how best to report a stolen instrument, and how to safeguard against buying or selling one.

When a violin expert spots a suspect instrument, authenticity and provenance (the history of ownership and possession) play essential roles in the analysis. In the case of the ‘Ames, Totenberg’ Stradivari, stolen in 1980 from violinist Roman Totenberg, violin expert Phillip Injeian used Herbert Goodkind’s Violin Iconography of Antonio Stradivari to establish a definite visual match between the suspect violin and the authentic stolen ‘Ames, Totenberg’. Injeian then searched online for ‘Ames Stradivari 1734’ and found the violin’s provenance in the Cozio Archive entry. This confirmed that the ‘Ames, Totenberg’ was indeed stolen property and Injeian quickly contacted law enforcement.

Roman Totenberg plays the ‘Ames, Totenberg’ Stradivari in the 1950s. Photo: courtesy of the Totenberg family, via NPR

Unfortunately, there is no centralized, all-inclusive, publicly accessible stolen instrument database available for those wishing to report thefts or check potentially stolen items. National registers such as the FBI’s National Stolen Art File and, internationally, Interpol’s Stolen Works of Art Database are freely accessible and an important resource for the public.

The Cozio Archive contains an important index of stolen instruments with links to photographs and details of the theft, and also provides a register of historical periods when instruments were stolen and later recovered.

A scattering of additional databases can be found online, including the Lost Art Internet Database, Maestronet and Musical Chairs. The Art Loss Register and Art Recovery International provide fee-based due diligence and claim recovery services. The contents of their databases are, however, proprietary and not searchable by the public.

Theft victims would also be wise to notify insurers, violin shops and auction houses, as well as trade and other organizations such as the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers, the Entente Internationale des Luthiers et Archetiers and the Violin Society of America, and trade publications including The Strad and Strings magazines. Although there are those who have argued that news of a theft can drive rare stolen cultural works underground, making them more difficult to recover, better outcomes appear to result from immediate and widespread publicity following the theft.

Although there are those who have argued that news of a theft can drive rare stolen cultural works underground… better outcomes appear to result from immediate and widespread publicity following the theft

This discussion is not intended to address the array of possible pitfalls that may be associated with a battle for ownership over a stolen violin. The laws regarding stolen property, the respective rights of the theft victim and the good faith purchaser, as well as potential defenses such as the statute of limitations, may vary dramatically depending on legal jurisdiction. But there is a need for due diligence by theft victims and others in the violin marketplace. Without it the passage of time may act as a shield, or a sword, to undermine a recovery or resolution of an ownership dispute, as some of the following stories illustrate.

Famous missing instruments

Of the many fine violins that have disappeared over the years, here are ten that are still missing:

1. The 1727 ‘Davidoff, Morini’ Antonio Stradivari violin was stolen around October 18, 1995 from a locked bedroom closet in Austrian-born violin soloist Erica Morini’s Manhattan apartment and replaced by an empty case. The door to the apartment was locked and there was no sign of forced entry. Morini, who was hospitalized at the time, died shortly thereafter at 91, not knowing that the Stradivari had been stolen. Despite a $100,000 reward the violin remains one of the FBI’s top ten unsolved art crimes. Morini’s brother, Frank, said of the missing Strad: ‘This violin is unsalable. Nobody in the world – a sane person – will touch this violin. It’s like fire.’

2. The ‘Mendelssohn’ Antonio Stradivari violin of 1709 was stolen in Berlin during the Nazi era after the persecution of the Jewish Mendelssohn family and the forced liquidation of the Mendelssohn bank in 1939. The Mendelssohn brothers, Robert and Franz, descendants of composer Felix Mendelssohn, both owned stunning stringed instrument collections. Franz’s daughter, Lilli von Mendelssohn, was an accomplished violinist and married Emil Bohnke, a violist in the Busch Quartet, and a composer and conductor. The 1709 Stradivari was last documented on December 18, 1940 as being located at 51 Jägerstrasse, Berlin, a Mendelssohn property taken over by the Nazis for the Reich Finance Ministry. Lilli Mendelssohn-Bohnke’s son, Walter Bohnke, reported that the Stradivari was stolen from the Deutsche Bank in Berlin upon the 1945 occupation of Berlin, but records from the Deutsche Bank Archive suggest the violin may have vanished before this.

3. The ‘King Maximilian, Unico’ Antonio Stradivari violin, also made in 1709, was stolen on May 29, 1999 in Mexico City. The theft appears to have been a planned residential burglary in which the violin was specifically targeted. Described by violin expert Emil Herrmann in his 1929 monograph on the ‘King Maximilian’ as ‘one of the most perfect creations of the master’, it bears the initials of Maximilian Joseph on its back below the button. The Axel Springer Foundation owned this instrument before it was sold to a prominent musician. A substantial reward has been offered for the return of the violin by a London insurer.

4. The ‘Le Marien’ Antonio Stradivari violin of 1714 was stolen in Manhattan, NY on April 9, 2002 from the violin shop of Christophe Landon, where the violin was consigned for sale by its owner, Barrett Wissman, a US entrepreneur with a passion for music and the arts. Landon remarked, ‘What I don’t understand is motive, because you cannot sell this violin, you cannot take it to an auction house, or to a dealer, because it is easily identifiable by an expert. It is like a Rembrandt.’ A $100,000 reward has been offered for the violin’s recovery.

5. The ‘Colossus’ Antonio Stradivari violin of 1716, owned by soloist Luigi Alberto Bianchi, was stolen in Rome on November 3, 1998. It was taken from the house of Bianchi’s mother, with no sign of forced entry. Bianchi had purchased the violin at Christie’s in 1987.

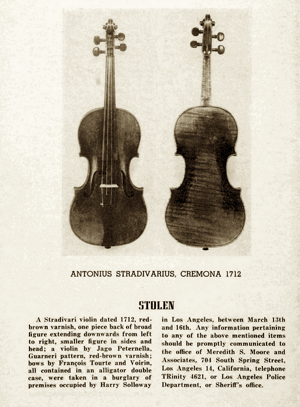

An advert from 1953 appealing for information about the missing ‘Karpilowsky, Benjamin’ Stradivari

6. The ‘Karpilowsky, Benjamin’ Antonio Stradivari violin of 1712 was taken in a burglary from the Los Angeles home of violinist Harry Solloway sometime between March 13 and 16, 1953. Solloway performed with the New York Symphony Orchestra under Walter Damrosch before moving to Los Angeles, where he continued his career in the Hollywood film studios. He placed a full-page advertisement for his missing violin in the May–June 1953 issue of Violins & Violinists to no avail.

7. The 1735 ‘Lamoureux, Zimbalist’ Antonio Stradivari violin belonged to violinist David Sarser before he discovered its theft from his New York studio on August 16, 1962. Sarser was the youngest member of Toscanini’s NBC Symphony when he acquired the ‘Lamoureux, Zimbalist’ in 1948. In 1983 Sarser received news from law enforcement authorities that his violin had been spotted in Japan, yet it remained elusive. He stated of his violin, ‘I have no desire to play any other instrument. It became part of me, and I became part of it.’

8. A 1675 Nicolò Amati violin belonging to violinist Takiko Omura was stolen in Tokyo on August 31, 2005. The windows in her home had been forced open and the thief broke into the locked cabinet where the violin was kept. Omura, who was 89 at the time, had played the violin for 50 years after purchasing it in the US in 1954. She said: ‘The violin is filled with lots of our memories. I feel as if I lost a friend.’

9. The ‘Hart’ Giovanni Battista Guadaganini, made in Turin in 1778, belongs to Minnesota orchestra violinist Chouhei Min and was stolen on May 16, 1999. Min and her trio had finished a church performance and briefly left their instruments in the church basement dressing room to attend the reception upstairs, during which time Min’s violin vanished. She said: ‘For me, it’s a part of my body, an extension of my arm. It’s been with me for so long.’

Notable recoveries

The return of the ‘Ames, Totenberg’ Stradivari bolsters hope that the future will bring more. Other important recoveries include the 1721 ‘Sinsheimer’ Stradivari, stolen from a residence in Hannover, Germany on October 17, 2008, but quickly recovered by police after a tip-off by an informant.

Min-Jin Kym’s 1696 Stradivari was stolen on November 2, 2010 while Kym stopped at London’s Euston Station for a sandwich. The thieves, a 40-year-old man and two teenage accomplices, were arrested in March 2011; they had made a failed attempt to sell the violin for £100 and it was finally recovered by police in July 2013. The Chief Inspector on the case said, ‘I always maintained that its rarity and distinctiveness would make any attempt to sell it extremely difficult, if not futile, because established arts and antiques dealers would easily recognise it as stolen property.’

The 1696 ‘ex-Kym’ Stradivari violin was recovered in 2013 after the thieves attempted to sell it for £100. Photos: Tarisio

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra’s 1727 Stradivari acquired in 1978 was stolen in 1985 from concertmaster Emanuel Borok’s apartment while he was in Europe. An adept former orchestra member spotted the violin when it surfaced two decades later at a Bonhams auction and a recovery was negotiated.

A brazen Taser gun attack on Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra concertmaster Frank Almond after a concert on January 27, 2014 resulted in the theft of the 1715 ‘Lipinski’ Stradivari, which Almond played on loan. The Taser gun released uniquely coded confetti at the scene of the crime that matched up to the gun and its owner, one of the thieves. This evidence, a hefty reward, an anonymous tip-off and great police work contributed to a swift recovery. Almost as audaciously, an Italian gang stole the 1717 ‘Kochanski’ Stradivari in 1987 from French violinist Pierre Amoyal and later demanded a ransom. Amoyal said: ‘I was followed out of my hotel by someone who knew I had the violin with me and was waiting outside… I felt as though I had lost my voice and a part of my spirit as well.’ Four years later the Carabinieri recovered the violin.

‘I was followed out of my hotel by someone who knew I had the violin with me and was waiting outside… I felt as though I had lost my voice and a part of my spirit as well’ – Pierre Amoyal

Joshua Bell’s 1713 ‘Gibson, Huberman’ Stradivari violin was missing for half a century before it surfaced. Julian Altman, a budding violinist, took it from Polish violinist Bronislaw Huberman’s dressing room at Carnegie Hall while he was giving a recital on his Guarneri ‘del Gesù’. On Altman’s deathbed in 1985 he told his wife the story of how he came to possess the ‘Gibson’; this story came out during a court battle between Altman’s widow and his daughter over the Lloyd’s of London finder’s fee for the ‘Gibson’.

One of the most unusual disappearances involved the 1732 ‘Duke of Alcantara’ Stradivari, on loan to UCLA’s resident Roth String Quartet member, David Margetts, in 1967. It vanished after an evening rehearsal in Los Angeles when the violin was either stolen from Margetts’s car, or, according to a police report, ‘It is possible the violin was left on the back of the car and fell off.’ Nadia Tupica, a Spanish teacher and string player, said she found it on the side of a Los Angeles freeway. She took the violin home and placed it beneath her bed, where it remained for years until she gave it to her nephew before she died. He passed it on to his ex-wife, who had the violin taken to the Joseph Grubaugh and Sigrun Seifert violin shop in January 1994.

As with the discovery of the ‘Ames, Totenberg’, red flags were raised for Grubaugh and Siefert when they confirmed the violin’s authenticity using Goodkind’s Iconography and discovered from the stolen property registry maintained at that time by the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers that it had been listed as stolen 27 years earlier. They immediately reported their discovery to the owner, UCLA, which obtained the return of the Stradivari, but not before an ownership battle waged in court for nearly a year.

From these stories of loss and recovery we find a mixture of crimes of opportunity and well-planned heists motivated by money and music. These plundered violins have languished in attics, closets and under beds, and perhaps under the chins of unsuspecting violinists. Hopefully, improving the reporting of losses so that they are readily accessible to the public will result in both enhanced recoveries for theft victims and less risk for the violin trade. The elusive stolen violin is never forgotten by its owner; an anguishing loss to the violinist, it also haunts the public imagination.

Carla Shapreau, a lawyer and violin maker, is a Lecturer and Senior Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley. She has written on many topics relating to the arts and is co-author of ‘Violin Fraud: Deception, Forgery, Theft, and Lawsuits in England and America’, Oxford University Press.

Cozio Stolen Instrument Register

See Cozio’s Stolen Instrument Register for a list of important missing instruments and to report stolen items; it also includes a Historic Register of instruments that have since been recovered.