We begin with Florentine Chanot, the first woman documented to have made violins under her own name. Her husband’s second wife, Antoinette Chardon, was instrumental in the success of the Chanot – Chardon business. Three generations later, Joséphine Chardon led the family firm into the modern era.

Florentine Chanot (1798 – 1859)

In 1821, Georges Chanot, the son of a successful Mirecourt violin maker and dealer, moved to Paris and set up shop in the stylish Place des Victoires. He was twenty years old and ambitious, so it comes as no surprise that he wanted to make a name for himself in the capital city. What was unusual, however, is that he hired a twenty-four year old unmarried woman to be his pupil and assistant.

Florentine Demolliens was born in 1798 in the small village of Saint Sauflieu, 150 km north of Paris. To the best of our knowledge, her family had no prior connection to violin making.[1] It was common in the 18th and 19th centuries for the wives, daughters and sisters of tradesmen to assist their fathers, brothers and husbands in the family business, but it is almost without precedent to have documentation of a woman, unconnected to the owner of the business, assisting in actual bench-work and making instruments of her own.[2]

Violins with an original label of Florentine Chanot have unfortunately not survived, but there are historical records of several instruments she made. The literary critic and musical historian Cyprien Desmarais referenced three violins by Florentine in 1836.[3] The first was exhibited in the 1827 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie Française (Exhibition of French Industrial Products). Demarais recounts that although Florentine’s violin was widely admired, the jury of the exhibition failed to give it a favorable recognition. By way of explanation, Desmarais lamely proposed, “to give the jury the benefit of the doubt, we should assume that they were paralyzed by the surprising fact that this masterpiece was made by a woman, and not that the jury was unwilling to give it the prize.”[4]

Although Florentine’s violin was widely admired, the jury of the exhibition failed to give it a favorable recognition.

A second instrument made by Florentine was commissioned by an amateur English cellist named Carleton.[5] The third was a violin made in 1829 for Jean-Baptiste Cartier. A student of Giovanni Battista Viotti, Cartier had been the violoniste accompagnateur of Marie Antoinette and then, after the Revolution, served as second violin at l’Opéra de Paris. He was an important musician, a member of la Musique de Napoléon for Napoleon’s coronation in 1804 and he played in the Cour des Rois under both Louis XVIII and Charles X.

At some point, the relationship between Georges and Florentine turned romantic. The couple had four children: the first was born in 1822 and died in infancy; the second was born a year later.[6] The future violin makers Auguste Adolphe and Georges were born in 1826 and 1831 respectively. Georges and Florentine married in June of 1826 when Florentine was six months pregnant with Auguste Adolphe.

Between 1839 and 1846, Georges traveled extensively to Spain, Portugal, England, Germany, Switzerland and to Russia where, in 1845, he met Comte de Wielogorski and Prince Youssoupoff.[7] We can imagine that Florentine was integral to the continuation of the business in Paris, as she would have been left to manage the affairs during his trips abroad.

Sadly, Florentine’s violin making career came to an abrupt and early end. Family letters mention that she became “atteinte de folie” (afflicted by madness). In August of 1840, Georges’s sister Barbe wrote and implored him to be patient with his wife: “Your wife must be in great pain. I urge you not to upset her and to have patience” (Il faut donc que ta femme éprouve de grandes peines. Je t’engage à ne pas la contrarier et à avoir beaucoup de patience).[8] Soon thereafter, Florentine retired to her hometown of Saint Sauflieu, where died on May 2, 1859, at the age of 61.[9]

Georges and Florentine’s marriage certificate. I scoured the handwriting of “Profession” for hours, hoping the notary would have recorded her as a violin maker until I realized it was a continuation of her name, “Marie Florentine Sophie…” Archives de Paris, État civil reconstitué (XVIe-1859).

Antoinette Chardon (1811 – 1892)

Around 1834 the Chanot family hired a governess named Rose Chardon to mind the young children while Florentine tended to the business. Rose had a sister, Antoinette, who was employed as a seamstress and lived a few streets away on rue de Rivoli.[11] In May of 1843 Antoinette gave birth to a son whom she called Joseph. There is no mention of the father in the baptismal register but Georges Chanot was the godfather and Marie Florentine Sophie Chanot[12] was the godmother.[13] Future developments would reveal that in fact Georges Chanot was the father of the infant Joseph Chardon.

Georges stayed married to Florentine throughout her illness, but three months after she died he married Antoinette Chardon.[14] The union was welcomed by the Chardon family but it was more complicated for Georges’s children, who were mourning their mother and had reasons to be concerned about their inheritance and the future of the family business.

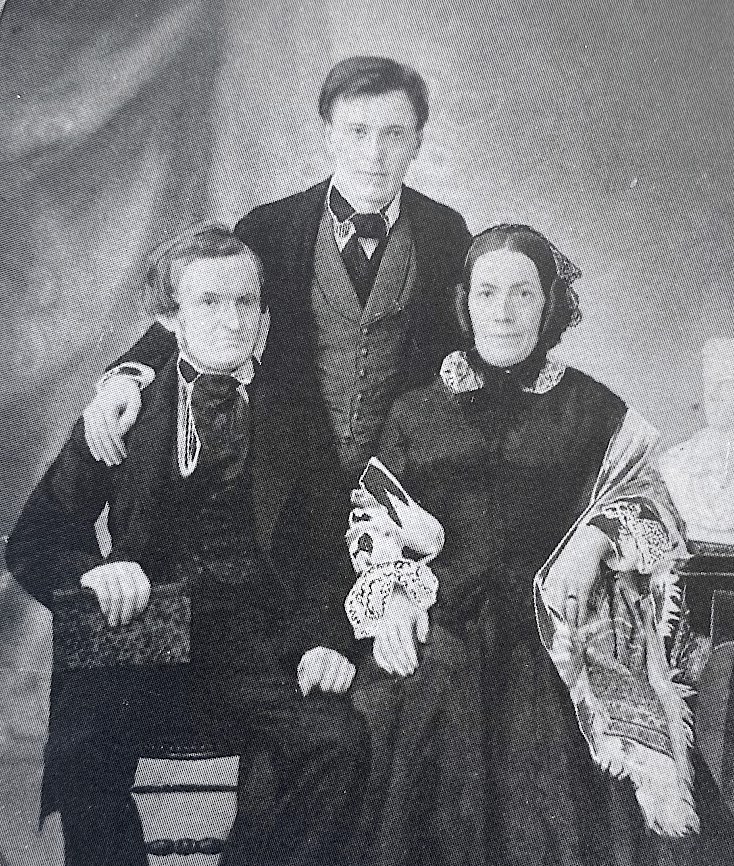

Georges Chanot with his second wife, the violin maker Antoinette Chardon, and their son, Joseph Chardon.

We know from correspondence and contemporary accounts that Antoinette also assisted in the workshop. According to the violin maker Pierre Vidoudez, Antoinette made Maggini model violins for the Chanot firm.[15] Unfortunately, we know of no surviving instruments which bear her signature or label.

We also know from family correspondence that Antoinette made rosin for the firm[16] and that she did work for her step-grandson, Georges Adolphe Chanot, in Manchester. In one letter, Georges Adolphe wrote to ask if his grandmother could make some violin parts (blocks) for him if she “has nothing else to do” and proposed to pay her twenty-five francs for the work. (“Si grandmama n’a rien d’autre à faire je voudrais bien pour 25 franc des taquets la plus grande partie pour violon.”)[17]

In one letter, Georges Adolphe wrote to ask if his grandmother could make some violin parts (blocks) for him if she “has nothing else to do” and proposed to pay her twenty-five francs for the work.

Antoinette retired with her husband in 1873 and moved to a house in the countryside south of Paris. She died nearly twenty years later in 1892. Her death register was witnessed by her son Joseph and by his neighbor, the violin maker, Hippolyte Chrétien who would later change his name to that of his maternal uncles, Hippolyte Chrétien Silvestre. Interestingly, the notary writing the death certificate mistook the name of Joseph Chardon and wrote Joseph Chanot.

According to Pierre Vidoudez, Antoinette Chardon made the Maggini model violins for her husband, Georges Chanot. This violin labeled Georges Chanot and dated 1835 was sold at Phillips in 1986 as “formerly in the private collection of Mme. Chardon.”

Joséphine Chardon (1901 – 1981)

Three generations later, another woman emerged as a powerful protagonist in the family business: Joséphine Chardon. The great-grand-daughter of Georges Chanot, Joséphine took over and ran the family firm in the mid-20th century together with her brother André.

Correspondence reveals an interesting detail about the siblings’ compensation. In 1919, André was twenty-four years old and working as a bowmaker in the family business. He made a salary of 135 francs a week. Joséphine, who was eighteen, received a salary of 20 francs per week.[18] Perhaps some of this disparity can be explained by the fact that Joséphine was still finishing school.

When their father died in 1950, Joséphine and André took over the shop. André was responsible for the expertise and Joséphine did general administration and took care of small repairs like gluings, edge repairs, fitting bass bars and varnish retouching.[19]

After André Chardon died in August 1963, Joséphine continued to run the business for nearly twenty more years until her death in 1981.

Letterhead of the Chanot-Chardon firm from c. 1868-1873. Collection du Musée de la musique / Cité de la musique – Philharmonie de Paris E.995.22.3127

Notes:

1. Florentine’s father was recorded as a marchand de crin or horsehair seller.

2. In contrast to Florentine, Georges Chanot’s sister Barbe assisted in the family business but did no actual work at the bench. The family correspondence shows that she negotiated prices with suppliers, arranged shipments of ebony and tonewood and reported information about competitors’ practices in the province. Barbe lived in the Chanot family house in Mirecourt her entire life and died unmarried. Her letters transmit her loneliness and the harsh cold winters of Mirecourt.

3. Cyprien Desmarais, Archéologie du Violon, Description d’un Violon Historique et Monumental, (Paris: Éditions Dentu, 1836), p. 20.

4. Ibid, p. 20. “On doit supposer, pour être juste envers tout le monde, que l’admiration du jury fut paralysée par l’étrangeté du fait, et qu’il aima mieux ne pas croire que ce chef-d’oeuvre de lutherie fût l’ouvrage d’une femme, que de lui décerner la palme.”

5. Ibid, p. 20.

6. There’s some discrepancy in the birth records for their first two children. According to the État civil reconstitué of the Paris archives, Charles Désiré was born on November 14, 1822 and, impossibly, Marie Florentine Sophie was born two months later on January 21, 1823. Charles Désiré died seventeen days after birth in the house of his grandmother in Saint Sauflieu and the death certificate corroborates his date of birth. The death record of Marie Florentine Sophie dated January 24, 1896 corroborates her birthday as well.

7. Sylvette Milliot, Parisian Violin Makers in the XIXth and XXth Centuries, Tome 1: The Family Chanot-Chardon, (Paris: Les Amis de la Musique, 1994), p. 31.

8. Letter of the 4th of August 1840, Collection du Musée de la musique / Cité de la musique – Philharmonie de Paris E.995.22.546.

9. Archives nationales, Minutier central, LVIII, 962: acte notoriété après le décès de Madame Chanot-Demolliens.

10. Milliot, p. 62

11. The baptismal registry of Marie Joseph Chardon in the parish of Saint-Roch, Paris, 1843. Collection du Musée de la musique / Cité de la musique – Philharmonie de Paris E.995.22.22.

12. Most likely this refers to Georges’s daughter and not his wife. The two had the same name.

13. Baptismal registry of Marie Joseph Chardon. Collection du Musée de la musique / Cité de la musique – Philharmonie de Paris E.995.22.224.

14. Milliot, p. 62. They wed on August 16, 1859. The witnesses at the wedding were his brother-in-law, the violin maker Sébastien Bernardel and the print dealer Alexandre Danlos.

15. Pierre Vidoudez, Georges Chanot Maitre Luthier 1801-1883, (Geneva, CH Pezzotti, 1974).

16. Letter from Georges Chanot to Joseph Chardon, 1878.

17. Letter from Georges Adolphe Chanot to his grandfather, Georges Chanot, dated October 18, 1881.

18. Milliot, p. 135.

19. Milliot, p.138. “Recollages d’eclisses ou de tables, de réparation des bords, détablages et rebarrages ainsi que raccord de vernis.”