We begin with Florentine Chanot, the first woman documented to have made violins under her own name. Her husband’s second wife, Antoinette Chardon, was instrumental in the success of the Chanot – Chardon business. Three generations later, Joséphine Chardon led the family firm into the modern era.

Florentine Chanot (1798 – 1859)

In 1821, Georges Chanot, the son of a successful Mirecourt violin maker and dealer, moved to Paris and set up shop in the stylish Place des Victoires. He was twenty years old and ambitious, so it comes as no surprise that he wanted to make a name for himself in the capital city. What was unusual, however, is that he hired a twenty-four year old unmarried woman to be his pupil and assistant.

Florentine Demolliens was born in 1798 in the small village of Saint Sauflieu, 150 km north of Paris. To the best of our knowledge, her family had no prior connection to violin making.[1] It was common in the 18th and 19th centuries for the wives, daughters and sisters of tradesmen to assist their fathers, brothers and husbands in the family business, but it is almost without precedent to have documentation of a woman, unconnected to the owner of the business, assisting in actual bench-work and making instruments of her own.[2]

Violins with an original label of Florentine Chanot have unfortunately not survived, but there are historical records of several instruments she made. The literary critic and musical historian Cyprien Desmarais referenced three violins by Florentine in 1836.[3] The first was exhibited in the 1827 Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie Française (Exhibition of French Industrial Products). Demarais recounts that although Florentine’s violin was widely admired, the jury of the exhibition failed to give it a favorable recognition. By way of explanation, Desmarais lamely proposed, “to give the jury the benefit of the doubt, we should assume that they were paralyzed by the surprising fact that this masterpiece was made by a woman, and not that the jury was unwilling to give it the prize.”[4]

Although Florentine’s violin was widely admired, the jury of the exhibition failed to give it a favorable recognition.

A second instrument made by Florentine was commissioned by an amateur English cellist named Carleton.[5] The third was a violin made in 1829 for Jean-Baptiste Cartier. A student of Giovanni Battista Viotti, Cartier had been the violoniste accompagnateur of Marie Antoinette and then, after the Revolution, served as second violin at l’Opéra de Paris. He was an important musician, a member of la Musique de Napoléon for Napoleon’s coronation in 1804 and he played in the Cour des Rois under both Louis XVIII and Charles X.

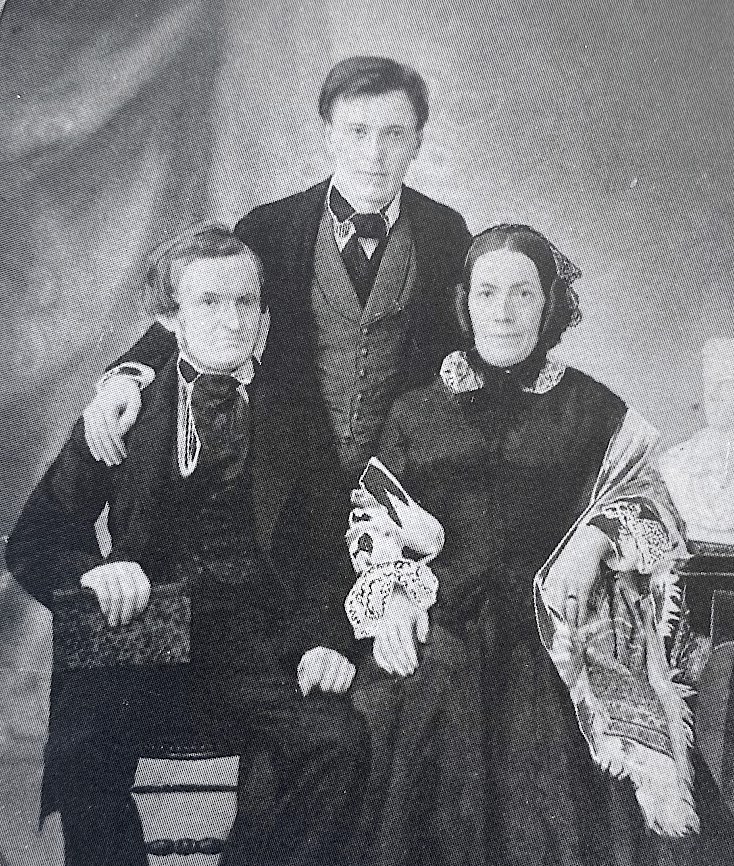

At some point, the relationship between Georges and Florentine turned romantic. The couple had four children: the first was born in 1822 and died in infancy; the second was born a year later.[6] The future violin makers Auguste Adolphe and Georges were born in 1826 and 1831 respectively. Georges and Florentine married in June of 1826 when Florentine was six months pregnant with Auguste Adolphe.

Between 1839 and 1846, Georges traveled extensively to Spain, Portugal, England, Germany, Switzerland and to Russia where, in 1845, he met Comte de Wielogorski and Prince Youssoupoff.[7] We can imagine that Florentine was integral to the continuation of the business in Paris, as she would have been left to manage the affairs during his trips abroad.

Sadly, Florentine’s violin making career came to an abrupt and early end. Family letters mention that she became “atteinte de folie” (afflicted by madness). In August of 1840, Georges’s sister Barbe wrote and implored him to be patient with his wife: “Your wife must be in great pain. I urge you not to upset her and to have patience” (Il faut donc que ta femme éprouve de grandes peines. Je t’engage à ne pas la contrarier et à avoir beaucoup de patience).[8] Soon thereafter, Florentine retired to her hometown of Saint Sauflieu, where died on May 2, 1859, at the age of 61.[9]