James Reynold Carlisle led the life of a Renaissance man. His is a story of violin making, varnish formulation, wood working, photography, painting and even growing prize-winning dahlias. Along this path he rubbed shoulders with Rudolph H. Wurlitzer, Rembert Wurlitzer and Henry Ford.

Reyn, as he was always known, was one of three children of a bridge carpenter for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, and was said to have been attentive to his father’s meticulous wood working. The Carlisle side of his family came from Louden county in Northern Virginia, often referred to as ‘Little Scotland’. Perhaps because of the nature of railroad work, Reyn’s father, William Walter Carlisle, ended up in Ashland, Kentucky. This is where he met his second wife, Elizabeth Huff, and where Reyn was born in 1886.

I have found no evidence from Carlisle or his family to explain why he started violin making, although he was from a music-loving family. According to John Fairfield’s Known Violin Makers, he made his first violin in 1910 and put it in his wife’s warming oven thinking this would age the wood – whereupon it promptly fell apart! At this point he was 24 and was working in Amelia, Ohio, an eastern extension of Cincinnati, which had been home to the Wurlitzer firm from 1856. In 1914 he somehow made the acquaintance of Rudolph H. Wurlitzer, 13 years his senior, and this was surely the turning point in his career. It seems he began working with the Wurlitzer firm in some capacity then.

Roughly ten years later the relationship between Carlisle and Wurlitzer becomes well documented. In 1925 the company produced their Rare Violin Catalog, and the General Merchandise Catalog of the same year features the violins of James R. Carlisle. There are three models shown, at prices of $75, $100 and $150, all featuring the Sunshine Varnish, which appears to have been Carlisle’s own invention and was so-called because it needed to be exposed to sunlight to work successfully. There is also an insert by American violinist Francis MacMillan in which he praises these violins and describes how he alternates between his Carlisle and his Strad.

About this time, another extraordinary thing happens: the making of a short motion picture, just over nine minutes long, by the pioneering American film producer William Fox, called The Violin Speaks. This was probably the first time that violin making had been the sole subject of a motion picture in the US, and possibly anywhere in the world. This short, subtitled piece shows the steps in violin making from the felling of a spruce to the beautiful sound we all know and love. The opening and closing shots show Carlisle’s own daughter, Dorothy, playing a violin in a serene lakeside gazebo. Not to be overlooked in the sections of the making of the violin is a young Rembert Wurlitzer. Here he is learning the art of making and assisting Carlisle, who was then aged about 40. According to various reference works and a 1960s newspaper article about a maker named Clyde Edwards, Carlisle only had two students, Edwards and Rembert Wurlitzer. The other person in the film is probably Edwards, who was born in 1908.

No doubt Carlisle needed help to produce the number of violins that would be ordered from the feature catalog of a firm as esteemed as Wurlitzer’s. These models always have an added line on the label, ‘alumnus Wurlitzer’, and are dated 1924 (all numbers printed). Some of the lesser models show details of more mass-produced work, although these are still of high quality, particularly the necks and scrolls. It is unclear when Carlisle left Wurlitzer’s, but his best handmade work starts to appear about this time and the peak of his production appears to have been around the late 1920s. His personal instruments are completely hand worked in all aspects. He had access to the ‘Betts’ Stradivari and the ‘LeDuc’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, as well as other master works, and used two models: a Stradivari and a Guarneri.

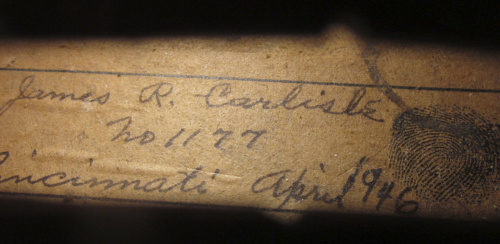

I believe Carlisle made many more violins than the 75 attributed to him in Wenberg’s The Violin Makers of the United States. I have seen over a hundred myself, and organized a group of 25 (including the only cello he made) for the Violin Society of America Study Exhibit of Ohio Makers in 2010. These spanned a timeline from the early 1920s to 1961, the year before he died. There is a label he used early on, in what I would call his experimental period, with a large font: ‘J.R. Carlisle’. Then there was the Wurlitzer label of 1924 and later a similar label, minus the reference to Wurlitzer and with handwritten dates, that he used for the rest of his life. These second two labels bear the famous thumbprint, but always printed on the label, not thumbed each time. There are also some instruments that were the result of a short-lived business agreement with a man named H.W. ‘Homer’ Beech. These are labeled Beech and Carlisle, but were not made by hand and perhaps use a Carlisle varnish.

Carlisle spent years experimenting with varnish. The result, ultimately, was a spirit varnish using a simple gum dissolved in alcohol. The color of this varnish ranges from a beautiful clear ruby red, to a wonderful orange–brown over a golden ground, again, very transparent and usually shaded.

I’ve read an account that suggests Carlisle procured a lot of his wood from the Lake Toxaway area of North Carolina, specifically from the Champion Paper and Lumber Company of Canton, North Carolina. An interesting aside on the matter of wood arises from his relationship with the automobile magnate Henry Ford. Ford, an avid violin lover and collector, wanted some Carlisle violins for his collection. Carlisle made some violins at Ford’s request, and as part of his thanks, Ford sent him a railway car of wood.

James Reynold Carlisle died in 1962. He had come a long way since the day he set out to age that wood in his wife’s warming oven, surely unaware that this was the beginning of a fine career: a robust relationship with the great Wurlitzer firm; violins featured in their major catalog; a personal friendship with Rembert Wurlitzer; being featured in perhaps the first-ever film on violin making; and a chance to handle some of the world’s great masterpieces; all mixed in with philosophy, photography, oil painting and cultivating dahlias. His was truly a life lived in full.

Bruce Babbitt is a violin dealer based in Delaware, Ohio.