What was going through the mind of James Montgomery Flagg when in 1907 he was inspired to set off from New York to explore the small village of Markneukirchen in the Musikwinkel region of Germany? He wrote that it was ‘a little newspaper clipping that suggested the idea’ but the clipping itself is lost to history. This much we do know: it resulted in a beautifully illustrated article, ‘A Violin Makers’ Village’, published in the February 1908 edition of Scribners Monthly. Scribners was a widely read periodical, published between 1887 and 1939. It was also one of the earliest magazines to publish color illustrations, and Flagg included two in color and several more in black and white. Some of its more famous contributors included Ernest Hemingway and Theodore Roosevelt.

Flagg is best known for the iconic recruitment poster he painted in 1917, with Uncle Sam pointing to the viewer and the caption ‘I want YOU for U.S. Army’. He began his career aged 14, making illustrations and contributing to Life magazine. He attended the Art Students League in New York and studied fine arts in both London and Paris, eventually becoming America’s highest-paid illustrator. He was also a portrait painter and among his more famous subjects were Mark Twain, Ethel Barrymore and Jack Dempsey.

James Montgomery Flagg’s famous 1917 recruitment poster

‘In the age when most things are turned out by the thousands with machinery,’ wrote Flagg, ‘we thought it would be refreshing to see a town where every one made things by hand, and particularly musical instruments.’ So, with his trunks packed with painting supplies and other tools of his trade, he set off to see for himself where the lion’s share of the world’s musical instruments were made. During the previous 50 years Markneukirchen and the surrounding area had sent many of its sons to the major cities of America, Europe and the Near East, and by 1907 Markneukirchen names like Albert, Friedrich, Gemünder, Martin, Voigt and Wurlitzer were well established in the US.

Flagg described Markneukirchen as ‘hundreds of miles from anywhere’ and complained that it was a full day’s train ride from Dresden, with a two-hour wait at Chemnitz station, and finally a bus ride ‘stopping at every twist in the road’ to get there. He was initially disappointed by the village’s appearance, having travelled through many picturesque towns to get there, describing it as ‘the apotheosis of the commonplace’ with ‘drab’ houses and ‘like a small English manufacturing town’. But, as he philosophized in the article, ‘that was only the outside.’

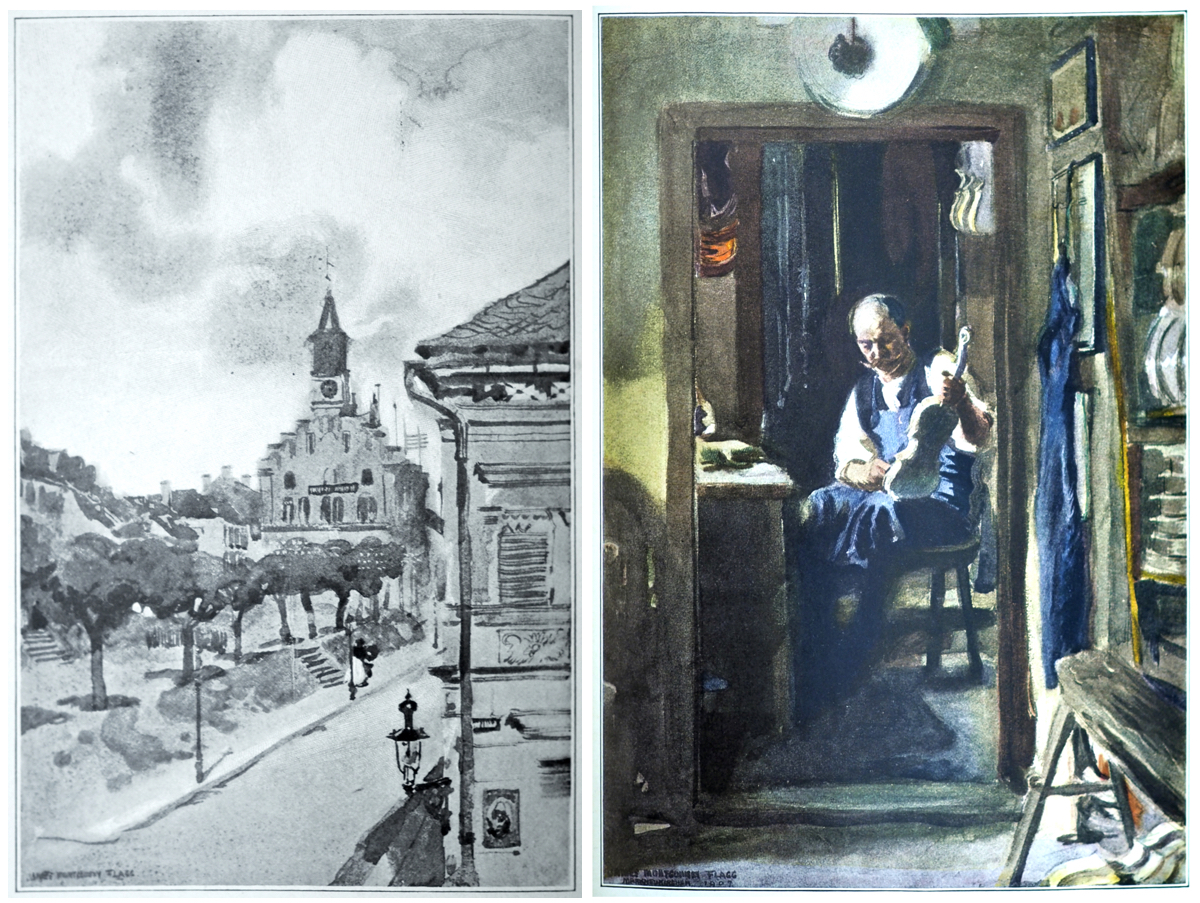

Flagg’s view of Markneukirchen and a violin maker at work

Soon upon his arrival at the Hotel Zur Post, now a business home for media and television, Flagg was introduced to a eager young man, Albert Theodor Heberlein. Albert’s training had taken him to places where he became adept at speaking English (probably the shop of Carl Fischer in New York), and he became the painter’s guide to the village. ‘He quite took entire charge of me and my project,’ wrote Flagg, ‘stopping work and changing from felt slippers and overalls into street clothes, no end of times, to take me to different factories and introduce me to the owners and explain my errand and argue them into sitting for me.’

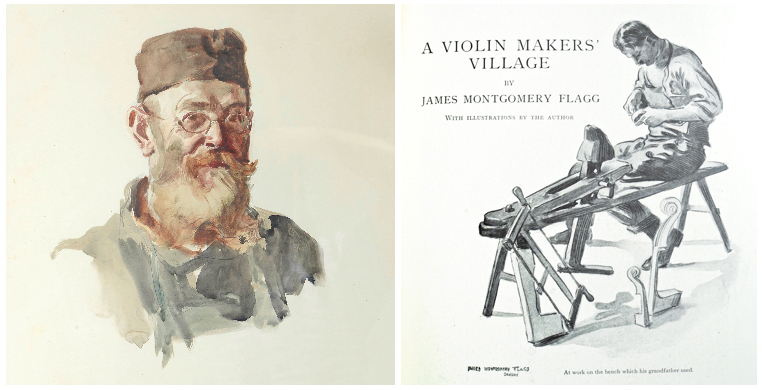

Heberlein was a ‘fine-looking old gentleman, who would resemble Tolstoi if Tolstoi had a kindly expression’ – James Montgomery Flagg

Flagg already knew that the most important violin maker of the village was Heinrich Theodor Heberlein Jr, Albert’s father. Of the many paintings and drawings that he was able to lay down during this visit, probably the most important was his portrait of ‘the modern Stradivarius’, as Flagg called the senior Heberlein (now in the Musical Instrument Museum in Markneukirchen). Heberlein, who was in his 64th year at this point and died only two years later, in 1909, initially refused to sit for Flagg, and only agreed after much coaxing by young Albert. Flagg comments that the elder Heberlein was a ‘fine-looking old gentleman, who would resemble Tolstoi if Tolstoi had a kindly expression’. Flagg also drew a sketch of the young Albert, which was used as the cover illustration of his article, captioned: ‘At work on the bench which his grandfather used.’

Flagg’s portraits of Heinrich Theodor Heberlein Jr (left, reproduced courtesy of the Markneukirchen Musical Instrument Museum) and his son Albert (right) who became Flagg’s guide to the village

For Flagg, there was a certain mystery about the sheer quantity of good instruments of the violin family that originated from such a small village. The key figure in explaining this is Heinrich Theodor Heberlein Jr, who was born in Markneukirchen in 1843 and initially trained with his father, Carl August Heberlein. He then moved to Hanover to be the first pupil of August Riechers in around 1860 and returned to set up his own shop in 1863. In the following years he won numerous awards, beginning in 1875 in Vienna and continuing up until the time of Flagg’s visit, taking prizes in Halle, Teplitz, Vienna again and Berlin.

Heberlein’s connection with Riechers, which turned into a lifelong friendship, proved important. Riechers was one of the leading violin connoisseurs at that time. He had himself trained in Markneukirchen and also with J.B. Vuillaume, and then worked in Leipzig for Ludwig Bausch. Most significantly, Riechers’ skills led him to a friendship with Joseph Joachim, who was the owner of numerous Stradivari violins over the course of his career. Riechers wrote a treatise, The Violin and its construction published posthumously in 1895, which is dedicated to Joachim and is centered on Stradivari. Thanks to his relationship with Riechers, Heberlein surely had the chance to study many Cremonese masterpieces, which greatly influenced his work. Interestingly, Flagg comments that among the finished instruments in Heberlein’s shop, ‘One violin was exhibited with great pride – it was very elaborately carved and the neck-piece was surmounted with a carved head of the famous Joachim.’

The earliest work of Heinrich Th. Heberlein Jr, despite receiving awards and acclaim at the time, seems to be as elusive as that newspaper clipping that got Flagg moving on his trip. The earliest instruments that I’m familiar with are violins dated between 1895–99. He is famous for being a fine imitator and he based his work on the models of Stradivari and Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, writing in a publicity statement that: ‘their instruments are the most beautiful in form and have the greatest sonority and the noblest tone quality.’ The violins from the late 19th century have a more true Cremonese arching and a more defined imitation as a whole, than the more commercial production by the Heberlein firm, although they lack the antiqued finish that the firm became known for after his death. It would be fascinating to have been in Flagg’s shoes and see first-hand what was lying about in 1907.

‘One violin was exhibited with great pride – it was very elaborately carved and the neck-piece was surmounted with a carved head of the famous Joachim’ – James Montgomery Flagg

Besides being a past president of the German Violin Makers Guild, Heberlein was one of the founders of Markneukirchen’s Professional School of Violin Making in 1878 and also taught there. However, most violin making in Markneukirchen was ultimately learned elsewhere and it seems to have been more of a preparatory school for younger students. Markneukirchen makers generally learned in the same centuries-old way: they apprenticed with their father or a family member, then took their journeyman’s exam and, having passed that, would generally then travel to study elsewhere. This is what led Heberlein to Riechers, and so it was with scores of makers.

Violin making, particularly as it pertained to Markneukirchen, is often a group process. This is particularly true if you are supplying violins to the world. There was a tradition in this small village of people being out-workers, supplying parts for general assembly in a more concentrated shop. The great firm of Hofner, founded in 1887 in the neighboring village of Schonbach, shows its first business entry as ‘sold four violin bodies in Markneukirchen’. There were Hälsechnitzer (neck carvers) and Korpusmachers (violin body makers) and many other specialist part makers. The level of skill was as high as we can imagine and ran through all levels of the business.

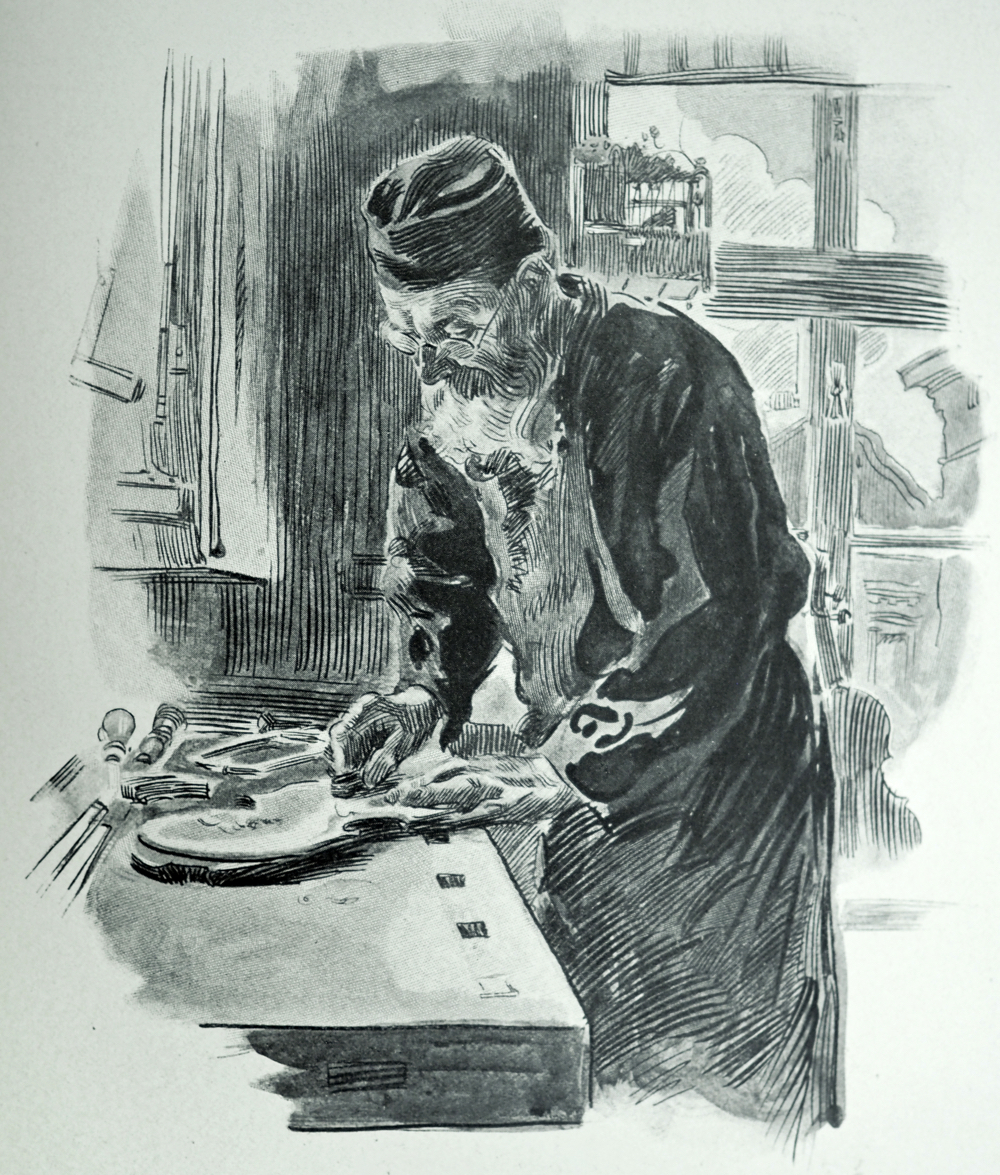

Captioned ‘an old violin maker at work’, this portrait might be of Heberlein himself

In the early 20th century, when the village and surrounding areas were bustling with orders (the US Consulate even had an agency there), the person at the top was Heberlein. His work was continued by his sons and in future generations by individuals such as Ernst Heinrich Roth, Paul Dorfel and Paul Knorr. Heberlein himself, and later the Heberlein firm after his death, helped to train many talented makers, including Arnold Voigt, Carl Adolf Zeitler, Kurt Gutter, Ernst Friedrich Reichel, Moritz Schmidt, and later Paul August Voigt and Kurt Richard Zophel.

Flagg notes the great pride that the Heberlein family took in their craft and describes their workshop in the article, mentioning the ‘tier on tier of violins in the rough’ which hung in a storeroom at the top of the house for two years to season before being varnished. The finished instruments were kept in a showcase in a small office as well as miniature instruments they made as recreation, ‘not over five inches long and exact in every detail.’

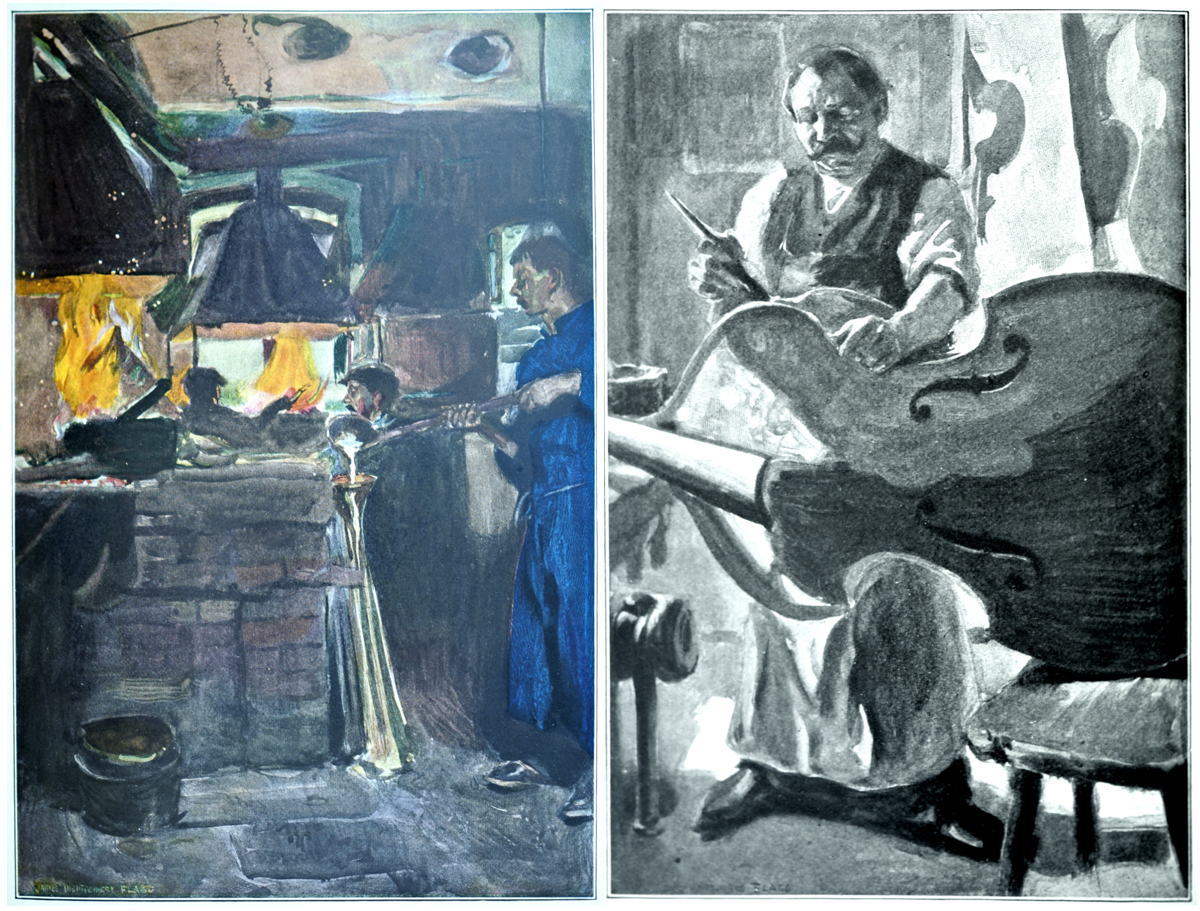

Watching melted lead being poured into a brass mold (left) and a bass viol maker varnishing (right)

Flagg gives a fascinating glimpse into life in the village, where apparently everyone worked and socialized late into the night. ‘Albert told us his father was sixty-five years old, but that it was seldom that he got to bed before one or two o’clock – a distinctly German trait, it seems – and was up every morning ready to work by six o’clock.’ Although in the daytime the streets were quiet, ‘at night and well into the most disreputably small hours of the morning the singing and laughing going on prevents strangers from getting much sleep.’

He watched the makers’ activities, some of them curious: ‘At four o’clock a whistle blew and all the workmen, long, short, lean and fat ones, all in blue blouses, piled out into the damp yard and, after refreshing themselves with coffee, they set off to pitch pfennings [German coins],’ and described the brass instrument makers firing the tubas: ‘When they put the tubas in the fire the most gorgeous lilacs and cherry and lemon-yellow flames spring up to envelop the horn.’ As well as making portraits of the Heberlein family, he drew the proprietor of a bass viol factory, who posed ‘in the act of applying varnish to a mammoth instrument’ and an assistant at a brass instrument factory, who to his amazement ‘held a six-foot iron ladle full of hot lead for a half hour without resting it against anything!’

Flagg’s short article was probably read by most at the time as an interesting and amusing account of a far-away place, but it has turned out to be an important portrait of musical instrument making in Markneukirchen a century ago.

Bruce Babbitt is the author of ‘Markneukirchen Violins & Bows’, published in 2014 (introduction by Enrico Weller).

James Montgomery Flagg’s full article is available to read online.

Further reading

Bernhard Zoebisch, Vogtlandischer Geigenbau, Geiger, 2002.

William Wisehart, Musikwinkel of Bohemia and Saxony in Markneukirchen and Bubenreuth Today, Bubenreuth, 2012.

Arian Sheets, An Overview of Violin Making in Egerland (Chebsko).

Christian Hoyer, 120 Years of Services to Music: A History of the Karl Hofner Company.