Although early American violin making was mostly influenced by makers trained overseas, there was one tradition that was strongly native grown: that of New England. Its earliest makers created instruments ‘on the fly’, basing their work upon instruments imported from Europe but with no prior experience other than skills in woodworking and ingenuity. This tradition started in the 1780s and continued, with methods codified by the leading exponents and passed on to their pupils, until the 1970s, at which time students began training at the German-oriented schools just developing around the US. One of the finest makers of this tradition, and in many respects its father, was an enterprising farmboy from western Massachusetts named Ira Johnson White.

Ira Johnson White

Ira White violin dated 1847 (head below), shortly after his adoption of Cremonese models. Photos: Robert Bailey, Tarisio

Ira was born in Barre, a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, in 1813. His father, John, was a farmer and shoe maker who also played the violin. According to a history of the family written by a local professor named Ed Wall in the 1970s, Ira showed great mechanical aptitude as a boy and was called upon to fix just about anything that was broken. Ira’s brother Lorenzo, who led a dance band in Boston, gave him a badly damaged violin, telling him that he could have it if he could fix it. Ira did just that, but his brother then reclaimed it. Ira thus determined to make one from scratch and did so in secret in the attic, his father being deeply opposed to this as he needed help on the farm.

Once Ira’s father saw the finished instrument, however, he was so impressed that he decided not only that Ira should be a violin maker in Boston but also decreed that the entire family should move there with him. While Ira might then have received additional instruction in Boston, he may simply have continued working by instinct.

One of the earliest surviving instruments from Ira’s hand is a violin of 1835, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts collection. It is modern in conception but naïve in design, loosely modeled after Amati, and marred by a muddy brown varnish. If an influence can be identified, it would be the types of commercial instruments then available for import from Saxony.

However, a major change was in the offing. In 1843 the Belgian concert artist Alexandre Artôt made his first visit to the US, performing in major cities along the east coast and bringing his Stradivari and Guarneri violins (he owned four Stradivaris during his career) with him. While performing in Boston he made Ira’s acquaintance and allowed him to study and measure the violins. Ira adopted these two Cremonese makers as his models and thereafter we see an ever-greater refinement and sophistication in his work.

However, a major change was in the offing. In 1843 the Belgian concert artist Alexandre Artôt made his first visit to the US, performing in major cities along the east coast and bringing his Stradivari and Guarneri violins (he owned four Stradivaris during his career) with him. While performing in Boston he made Ira’s acquaintance and allowed him to study and measure the violins. Ira adopted these two Cremonese makers as his models and thereafter we see an ever-greater refinement and sophistication in his work.

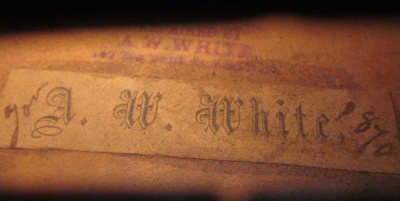

From 1844 until 1849 Ira worked in partnership with his brother James Henry White (1817–1882), who was a violinist as well as an instrument repairer; then from 1849 until 1863 he worked in partnership with another brother, Asa Warren White, as the White Brothers. After 1863 Ira moved to Malden, north of Boston, where he continued to make violins and then, after 1871, to nearby Melrose, where he died on December 19, 1895.

Ira’s influence was far-reaching. At the time his work was far and away the finest quality of any being created at that time in New England. Furthermore, he taught a variety of apprentices who in turn established their own workshops. Key among these was Edmund F. Bryant (1855–1940), who taught his nephew Ole H. Bryant (1873–1943), who in turn became the most influential of early 20th-century New England violin makers and was nicknamed ‘the American Vuillaume’. Ole eventually started his own violin making school, and in his workshop many of the finest talents of 20th-century Boston lutherie learned the trade.

Asa Warren White

Asa Warren, known to his family as Warren, was born in Barre in 1826. He was still a child when the family moved to Boston and there he worked under the guidance of a French guitar maker named Giraudot, who was employed briefly in Henry Prentiss’s well-known Boston music shop in 1843. He then learned violin making from his elder brother, Ira, and 1848 joined Ira as a partner; by 1849 the brothers were working together under the name I. J. and A.W. White, a version of Asa Warren’s name that he would continue to use on his labels. After the dissolution of their partnership in 1863 Asa Warren set up his own workshop at 86 Tremont Street, where he advertised a wide variety of musical instruments, including woodwinds, brass and drums, as well as bows and musical supplies. He also invented a folding music stand and co-invented a chinrest.

Massachusetts also had a long-standing trades fair, run by the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association, and violin making was a regular category in these events. While not unique to the country (the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia sponsored similar events), they were long-running and occurred regularly. Ira and Asa Warren frequently competed, and both earned both gold and silver medals for fine workmanship.

Asa Warren White violin made in 1874, during the period of his partnership with a guitar maker named Louis Goullaud. Photos: Robert Bailey, Tarisio

In 1869, while in partnership with a now-unknown guitar maker named Louis Goullaud, Asa Warren wrote a book called The Violin / Some advice in selecting both the Violin and Bow / How to keep them in order, published in 1875. It was among the earliest primers on violin making published in the US. Asa Warren and Goullaud worked together until 1876, when Asa Warren left, moving to another location. In 1879, after his wife died, he moved briefly to Chicago, where he made at least one violin dated 1880, but returned to Boston within the year, opening a shop down the street from his old Tremont Street address. To judge by another recently discovered violin, which like the 1880 violin has ‘Chicago’ noted on its original label, he returned to Chicago briefly in 1886. One wonders whether he had any contact with Hermann Macklett, the premier maker in Chicago and often considered the father of the craft in that city, during his two visits. Back in Boston he continued inventing, securing a patent for a laminated pernambuco violin bow.

However, indications are that Asa Warren’s business was flagging, for in 1889 he moved it yet again, to an unfashionable address in South Boston, and then closed it completely in 1891. In an attempt to salvage his trade he revised his 1875 book, adding chapters on violin making and varnishing, and retitling it The Violin / How to construct from beginning to completion… It was published in 1892. While largely a rehash of the earlier book, it contains interesting observations and notes about violin making and the trade in those years. Two years later, on November 12, 1894, Asa Warren died in poverty and was buried in an unmarked grave.

If Asa Warren was less successful than Ira, his influence was equally significant. He is today given his due as a fine violin maker whose skills rivaled those of his brother, but it is through his students that he left his strongest imprint on the Boston trade. Among Asa Warren’s pupils and apprentices were three of the most important names of late 19th- and early 20th-century New England violin makers: Calvin Baker, Orin Weeman and Treffle Gervais. These three eventually ran important workshops and in turn trained more of the makers who would determine the craft’s future in New England.

Philip J. Kass is an expert on classical violin making and has contributed extensively to the Journal of the Violin Society of America, The Strad magazine and the New Grove Dictionary of Music. Read the full version of his feature on the White brothers in ‘The American Violin’ recently published by the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers.