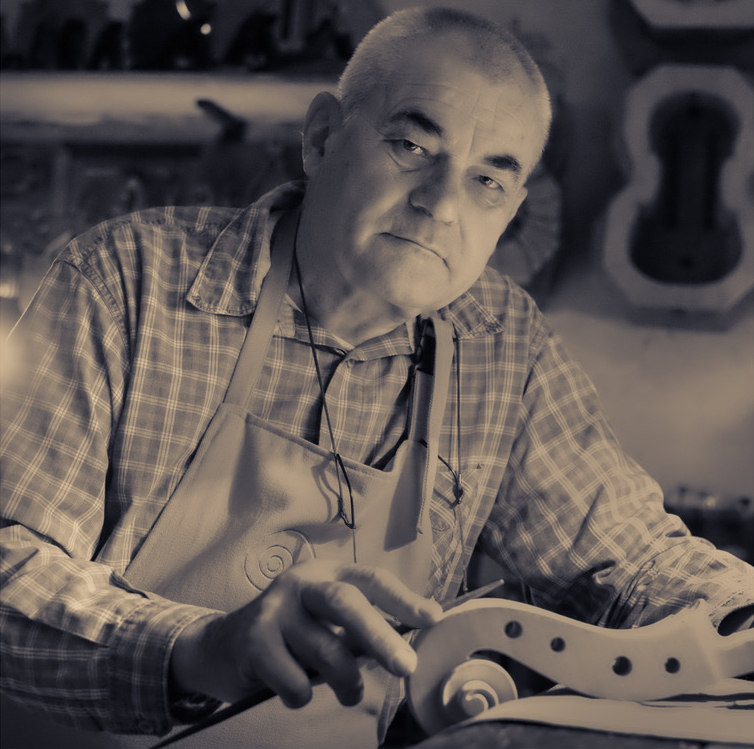

Simplicity and normality appear to reign in Stefano Conia’s tranquil workshop, nestled in a courtyard garden typical of Cremona’s historic town center.‘Violin making is a very normal job,’ he told me in our interview, although paradoxically he was also keen to let me know that the Cremonese craft is designated by Unesco as a ‘living human treasure’. He certainly takes a very practical approach to his work, using both an internal mould and an external one for certain models: ‘If the internal mould is being used then I’ll just grab the the external one.’ Surely the age old internal/external mould dilemma is not this simple? So simple that it can be resolved as easily as choosing the right pot for the spaghetti? I have the impression that Conia has learnt to adapt to violin making’s demands – and indeed life’s – in this practical and straightforward way to create something of beauty and of lasting value.

The following interview with Conia is translated from the original Italian.

The situation in Hungary before the war was a critical one, with real poverty. After the war my father [the maker Istvan Konya; Conia has since Italianised his name] wanted to defect, but he was betrayed by someone who told the police that he was planning on leaving with his whole family. My brother was too little to walk but I was walking and they caught us near the Austrian border. My father was accused of defecting and put in prison for five years.

Conia made his first knife from some old steel. Photo: Paul Sadka

This was in 1950, when I was five, and so for a few years my brother and I grew up in the countryside to the north of Lake Balaton without a father. An interesting thing about my father, which was perhaps instrumental in my development, is that he continued making violins while in prison. It brought him certain benefits, not financial ones but favorable treatment – he was privileged. He made a violin for the prison governor and he managed to get a violin out to us that was built out of wood from a wardrobe. I have it even now as a keepsake. I had my first lessons on it when I was about six or seven. My teacher was the leader of a gypsy band – there were so many at the time. I used to walk four kilometers on foot with this instrument to Balaton Füred for my lessons. I have always played the violin but I had to stop a few years ago as work has taken its toll on my hands. Playing the violin and making cellos are not really compatible!

Certainly it was difficult in those years in Hungary. As a child though you don’t realise. A child doesn’t have much in the way of needs – to play, to eat. One way or another we managed. The women at the time would queue from morning till 5pm for half a kilo of meat, knowing full well that at 4pm they might be told that the meat had run out. We lived from hand to mouth, wild almost, without shoes or many clothes. Looking back as an adult of course I realise that we had nothing compared with the children of today. They might have given me a banana or an orange as a birthday present. But in the countryside you could get hold of grapes, apples and pears. We used to steal cucumbers and peppers from gardens. We even ate baby birds from nests. There was no TV or radio, no water, or electricity or gas in the house. We spent our lives playing with the neighbors’ children. We played football from straight after breakfast, if there was any, until sunset if no-one called us back. Quite a training regime!

Conia’s workshop looks on to a tranquil courtyard. Photo: Paul Sadka

We were in Balaton during the revolution of 1956. It was ‘soft communism’ there as it was a provincial tourist town, and I don’t think we even saw one tank. But we heard all the broadcasts and we began burning books written in Russian, and we began to study German. In six months we could speak and read in German. It was our way of rebelling against the oppression and the compulsory study of the Russian language.

We moved back to Tatabanya, where I was born, after 1956, when they returned our father to us. He had become a photographer by then, and we’d made a bit of money, bought a house and I could go to the music school. I played second violin in the Tatabanya Philharmonic Orchestra.

I’d seen my father making violins at home and I said to him that I thought it looked easy. That got him angry

By the time I finished high school I’d acquired some manual skills doing sculpture and painting. I’d also done some work on the engines of old cars. I’d seen my father making violins at home and I said to him that I thought it looked easy. That got him angry and he said, ‘OK then, here’s some maple and spruce, get on with it. I had no tools, nothing! So with my limited savings I bought a couple of chisels and gouges, and made a knife out of some old steel. I couldn’t touch my father’s tools – that would have meant big trouble. And so I made my first violin before doing military service when I was 18. It was an Amati model and I played on it for a while. After the army I’d wanted to become a surgeon, or a doctor, but it was so difficult in Hungary, with 1,500 applicants for 120 places. I tried two or three times. Besides working in a hospital at that time I also worked in a mine.

Ironically I spent my 27 months’ military service as a border guard. In the meantime, in 1966 my father (who had first started making by copying a German factory model) had got his diploma from the Cremona school. When I’d finished in the army my father recommended me to the directors at the Cremona school and they agreed to take me. There was far less demand for places at the time. In fact there were only 18 students in total, and on account of my violin playing and my ability to speak English it was decided that I could come and study in Cremona.

Bridges hanging in the workshop alongside a pochette mould. Photo: Paul Sadka

Many more foreigners arrived after me but there were very few at the time and I was a novelty. And so I received many invitations to eat pizza out in the local restaurants. I had no money then and I repaid this generosity by doing little jobs for people. For example, if an old lady had a broken lock I’d repair it, or if her iron wasn’t working I’d sort that out. I enjoyed the school, particularly my classes with Morassi. He discovered me, you could say, and I would visit him in his workshop. One day he said, ‘If you’d like to rough out a cello for me then come along,’ so I did. He was from Friuli and hard, strict and precise. He was also ambidextrous. He’d pass the scroll from one hand to the other, turn it around and work it in exactly the same way as the side he’d just done. That’s a significant gift. I can’t do it! I was with Morassi for two or three years and he helped me find my first clients too.

It was quite a thing in the 70s and 80s, whether one should use the external or the internal form, but it really doesn’t make much sense. All over the world there are thousands of violin makers who make violins in many different ways. There are some who don’t even use a form at all. It’s the experience and expertise that matters. I use both and for example I have an internal and an external form for the 1715 Stradivari. It’s well known that the internal form offers greater freedom of expression in the moment, both by way of outline and execution. With the external form the outline comes out perfect and symmetrical, which isn’t always the case with the external form. Even on Stradivari’s instruments the symmetry can be out by four or five millimetres. If we were to make instruments like Stradivari today no one would buy them. These days it’s not enough that our instruments play well. The Japanese and American dealers come here with their rulers and measure before buying. If it’s out by one or two millimetres then they don’t want it.

If we were to make instruments like Stradivari today no one would buy them

I make no distinction between art and craft. The Italian dictionary says that a liutaio is an ‘artefice’ – an author or creator of musical instruments. Some say violin making is an art. For me it’s a job, and now that I’ve been doing it so long it’s a very normal job. However, if you think about it the violin maker is also a sculptor. And I believe that varnishing is very close to painting. And then there’s the sound. The maker who plays is also a musician. We can say perhaps that it’s a complex art. It can’t be for nothing that Unesco has given us the title ‘a living human treasure’ – it’s not a simple job.

I don’t think there’s any trace of Hungarian style in my work. We in Cremona are too attached to the Italian tradition. It’s more probable that you can see the style of Hungary in the work of those Hungarians who visit Cremona – my brother and my nephew for example. My father went home to work once he had his diploma and he developed a style of his own with Hungarian influences. He’s done his own thing with the scroll and he accentuates the arching. I like the style of these makers. They have developed an expressive character and an individuality all their own. I taught about four or five Hungarians in my 23 years at the school and they have now returned and are carrying on the tradition. These Hungarians are in a way my ‘figli d’arte’ – they come back and visit me. When they were students they would come to me if they needed money. I lent them my tools and taught them how to varnish – that’s how it was with the Hungarians.

My parents are gone now, but my brother is always visiting. I no longer have any real desire to travel. I like it here. I’ve been retired officially now for five or six years, but I’m still working – what would I do otherwise? I’ve got my hobbies. I ride racing bikes, and I’ve got my classic cars and I work on their engines. I’ve given my motorbikes away though. Sgarabotto had a classic Guzzi and I had several bikes. The last one was a 500cc which I exchanged with Giorgio Scolari’s brother Daniele for a violin. He didn’t have any money but he told me he really wanted the bike. Obviously I got the better deal. I’ve had enough of motorbikes – several of my friends and acquaintances have had fatal accidents.

I say that it’s a violin maker’s good fortune that he does a job that he enjoys. A violin maker who’s also a good administrator won’t die of hunger, that’s for sure. I would have gladly been a surgeon or a doctor, but at least I don’t get called out in the middle of the night for emergencies. It does happen that I’m called for violin making emergencies, and I’m happy to do that, even on a Sunday if need be. Violin making is hard work, mind. Roughing out the arching of cellos makes you sweat. It’s all relative though, a well-made violin sells for €10,000 these days. I wouldn’t change profession!

Paul Sadka is an award-winning bow maker currently working in France.