Photo: Dorothea von Haeften

Arnold Steinhardt was introduced to his Lorenzo Storioni violin by Mischa Schneider, cellist of the Budapest Quartet. The group had just retired and Schneider suggested Steinhardt might like the instrument that belonged to its first violinist, Josef Roisman, so Steinhardt traveled to Washington: ‘I met Roisman and his wife, played the violin and loved it. It had a big, dark, unusual sound.’ But Roisman wasn’t ready to part with it. He told Steinhardt, ‘I’ve been thinking about this. I like getting together with friends to play chamber music every Friday night. I’ll sell you the violin but I want to keep it for a while.’

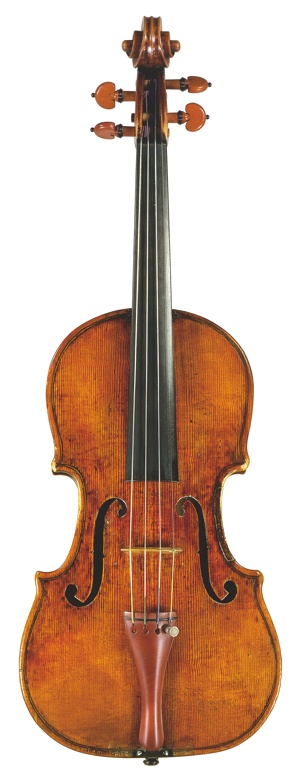

After Roisman’s death a year later Steinhardt was able to buy the c. 1785 Storioni. When he took it to Jacques Francais in New York he discovered the secret of its special sound. He recalls, ‘Jacques said, “Mon ami, this is not a violin. It’s a viola!”’ There were more revelations. According to Francais, the instrument’s scroll was made by Guarneri ‘del Gesù’. Francais had a Storioni viola scroll that matched the violin and was eager to trade, as he was working on a ‘del Gesù’ with the wrong scroll. Steinhardt explains, ‘There was a shop where the guy was a bit of a crook, doing terrible things with instruments, dividing them up and doing things we don’t want to know about. Francais said that the Storioni scroll came from that shop and it might be that the viola and his scroll were original partners – they have the same color.’ The swap was made and the Storioni body now has a matching, if somewhat oversized, scroll.

No one knows when the instrument was originally cut down, although Steinhardt has papers going back a hundred years to the original Budapest first violinist Emil Hauser, who bought it as a ‘del Gesù’. According to Steinhardt, cut-down Storioni violins are not unheard of: ‘Since I bought it I’ve come across at least two or three Storioni violas that have been made into violins, although none of them as successfully as this one. It has a rich middle and lower register but I have to be careful in the higher register, because it’s never quite forgotten it’s a viola. I have to take measures to fill in the sound on the E string: I probably use more bow or bow speed than I would with a more traditional-sounding violin. I use thick E strings because they put some fat on the sound.’

Storioni violin, c. 1785. Photo: Stewart Pollens, courtesy The Strad

![]()

It’s not just the sound of the instrument that he finds compelling. ‘It’s remarkable for the varnish and the quality of the wood, including the fact that Storioni used wood with flaws. It’s beautiful and gives real character to it.’ He sees similarities with the ‘del Gesù’ style: ‘There’s a rough-hewn beauty.’

The instrument Steinhardt played before the Storioni was, indeed, a ‘del Gesù’, now known as the ‘Beare–Steinhardt’. People are surprised when he tells them this: ‘They say to me, “You had a ‘del Gesù’ and you traded it in for a Storioni?”’ The instrument had been in the possession of Arthur Beare, father of Charles, and had lain in pieces, believed for many years to be a John Lott, before being reassigned. It wasn’t in a particularly good state, as he describes: ‘Someone had stripped the varnish and revarnished it poorly. They had also tampered with the f-holes, giving them a Gothic edge to make them look later, although it was from 1738, late enough for a “del Gesù”.’ The violin arrived at Wurlitzer’s in New York, where Sacconi removed the varnish and put on his own. Steinhardt came into the shop at the right time: ‘Sacconi said, “I have an instrument for you to try”, and I loved it. It had this lush, dark sound and a complexity to it that I instantly loved. So I bought it.’

How do these two great instruments compare? ‘The “del Gesù” had a lovely, somewhat husky, dark sound, but it also had a smoothness and refinement to it that just didn’t have quite enough point to it to project well. The Storioni is a little brash sounding. It’s a rich, chocolate sound, but it also has an edge to it. I imagine if you were looking at the whole tonal scale, the upper and lower registers would be prominent and maybe the middle not so much. It has a deep-throated quality that people comment on.’

The Storioni’s back has ‘real character’. Photo: Stewart Pollens, courtesy The Strad

Steinhardt is a keen advocate of modern instruments. ‘It’s a nice idea to play contemporary violins and to have a relationship with contemporary makers, as people did in Strad’s time.’ He owns a viola by Hiroshi Iisuka and a violin by Sam Zygmuntowicz, which he alternates with his Storioni over periods of time. ‘[The Iisuka] has a healthy, natural sound. It’s in the middle in terms of treble or bass and it gives you the possibility of doing all kinds of things with the sound.’

The 2006 Zygmuntowicz violin ‘tips its hat’ at the Storioni: ‘It doesn’t sound like it but it has a large and darkish sound.’ The instrument has developed since he has owned it: ‘I got it when it was brand new and of course it has changed. The bass-bar had to work in, so it was a bit raw-sounding and now it’s much smoother. The sound has become clearer and more focused. It was a healthy sound right away, but the rawness has disappeared and there’s a nice sheen.’

Steinhardt is also a fan of modern bows and although he has owned bows by Maline and Peccatte in the past, his only old bow now is a Voirin. ‘There are so many fantastic contemporary bow makers now and they all make bows that are different, so you can go to a shop and try them all.’ His main bow is one by American maker Morgan Andersen.

The ‘Beare–Steinhardt’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’

For any player there is a learning curve in buying instruments and bows, as Steinhardt describes: ‘When you’re a student, unless you’re unusual, you don’t know very much about the nature of the violin business, or about sound. As a student I really didn’t know what kind of violin I would want if I had my perfect instrument. I was too inexperienced.’ At that stage he had good instruments but none that he truly loved. His first serious violin was a Pressenda, which he describes as ‘healthy sounding’. ‘Then I went to a Santo Serafin, which was elegant and much more refined in sound. It didn’t have the volume of the Pressenda, so I went to a Lorenzo Guadagnini, which was one of the most beautiful violins I’ve owned, although it turns out that the instruments attributed to him were made by Mantegazza and others*. It was a very good violin and I could have played it for the rest of my life, but I simply didn’t love the sound.’ (* See Duane Rosengard, Giovanni Battista Guadagnini)

By the time he walked into Wurlitzer’s and discovered the ‘del Gesù’, he had a sense of what he was looking for. ‘At that point I was beginning to know what I wanted. I didn’t like shrill, edgy violins. I began to lean more to dark-sounding instruments. I didn’t know at that point that there was a danger in getting a violin that was too dark because the sound might not project and you might get tired of it. You wouldn’t be in the middle sound range to be able to work the strings to get a more treble sound. That’s the kind of thing I learnt.’

Clearly Steinhardt gravitates towards the ‘del Gesù’ sound, although he has played Stradivaris many times. Has he ever wanted to own one? ‘There are Strads I would have died to have. A student came in for her lesson at Curtis and all she did was tune and I heard this golden sound.’ The instrument turned out to be a Strad. Would he have swapped it for his Storioni? He shoots back, ‘Don’t ask me questions like that!’

The Guarneri Quartet onstage in 2009, joined by original cellist David Soyer

But instincts are important, as he explains: ‘If you are thrilled by the sound of an old Italian violin under the ear, it gives you the inspiration to do things you might not attempt if you weren’t so excited, even if the one that you didn’t like so much is said to be a better violin. That’s a really important aspect of the whole thing. I’ve been thrilled to have my Storioni even though he’s supposedly one of the lesser Cremonese masters. I don’t think that – I think he was a genius.’