Technological advances over the past fifty years have enhanced the study and trade of historical stringed instruments. Digital photography, dendrochronology, ultraviolet spectrology and computed tomography have each changed the course of expertise, protected consumers and brought forward the industry. This year Tarisio has pioneered the application of infrared imaging, a technology that I believe will be a quantum leap forward in understanding the condition and state of restoration of fine stringed instruments.

Infrared imaging in Tarisio’s New York photo studio. Infrared will open up new, efficient and nondestructive methods for understanding and documenting an instrument’s condition.

Infrared is invisible to the human eye. Its wavelengths are longer than those of the visible spectrum, perceived by humans not as light but heat. There are many scientific applications of infrared technology in medicine, astronomy and telecommunications; art conservators use infrared reflectology to reveal a painting’s previously unseen underlying layers. And in the field of fine instruments, infrared imaging will open up new, efficient and nondestructive methods of documenting an instrument’s condition.

Pablo Picasso, The Blue Room (1901), The Phillips Collection. Daylight (left) and infrared (right). An earlier portrait of a man is visible under infrared imaging.

At the other end of the spectrum lies ultraviolet light, used by violin restorers since the mid-20th century to differentiate between retouched and original varnish; to identify areas of previous damage; and to confirm the originality of parts. Experts and restorers rely on ultraviolet analysis to corroborate an instrument’s condition and authenticity. But while ultraviolet examination evaluates the reflection of UV light on the surface of an instrument, infrared can pass through low-density objects like violins to allow an observer to create an x-ray like image that shows what’s happening inside the wood itself.

If you hold a thin piece of maple up to a light source, the grain and flame of the wood appear in high contrast. Dense areas, like the maple’s hard winter grains, appear dark, while thinner areas of the wood appear lighter; hollow areas and abscesses can seem almost white. But even the most powerful light source can’t shine through more than a millimeter or two of maple. Infrared, on the other hand, can easily travel through several centimeters of soft materials such as maple or spruce. And although it’s invisible to our eyes, infrared can be captured with a modified camera sensor.

A normal light source passing through a thin piece of maple reveals the grain and flame in high contrast. Photo: Anton Somers.

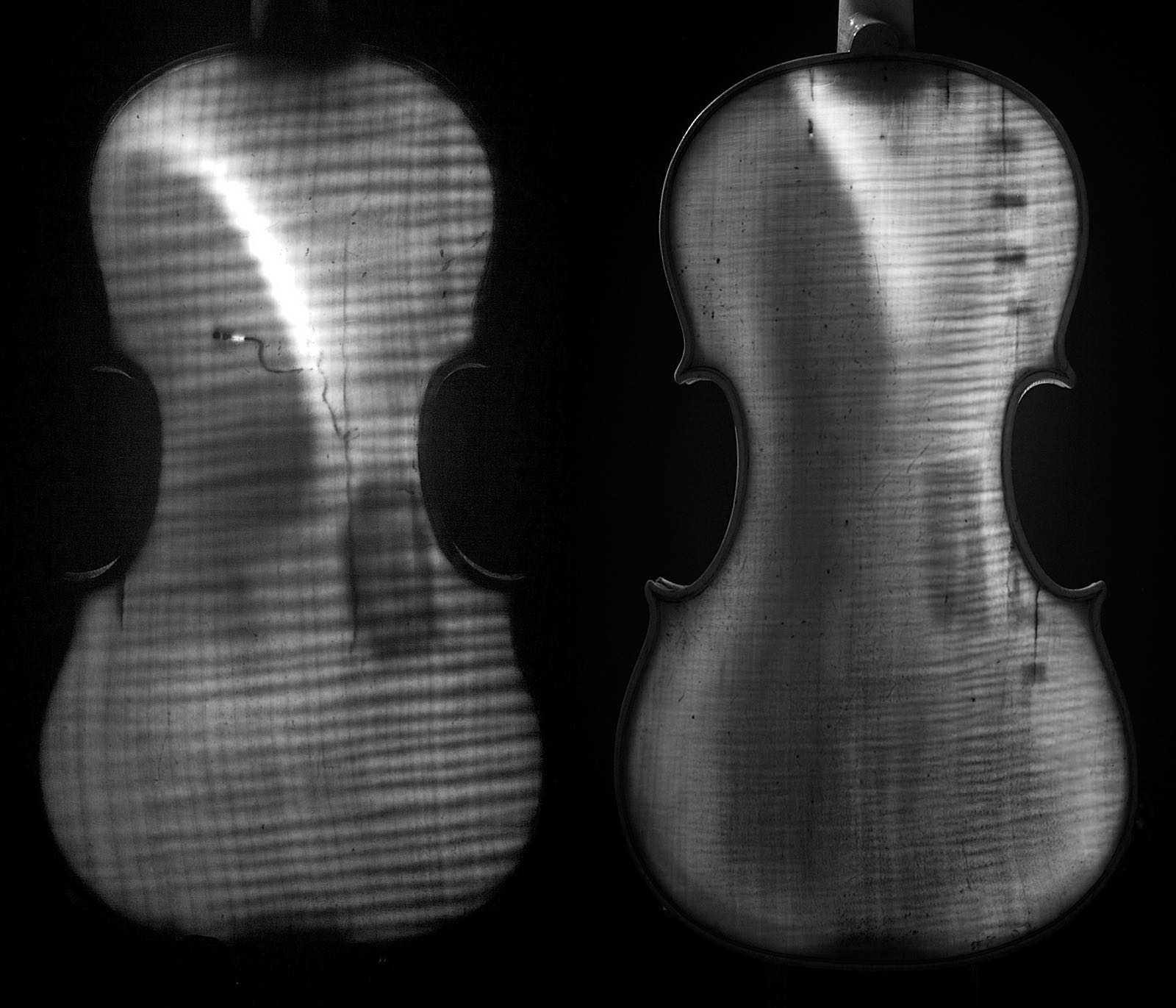

Here’s the fun part: My colleague in Cologne, the violin maker and restorer Leonhard Rank, has developed a system to photograph musical instruments with transmitted infrared. Special LED lights which emit infrared are positioned inside the instrument through the sound holes. Tethered to a computer, a modified digital camera captures the transmitted infrared over a long exposure and outputs a visible image. His system is simple and brilliant.

An LED source placed inside an instrument transmits invisible infrared that a modified camera captures and translates into an image revealing woodworm, cracks, patches and cleats.

Infrared imaging can see things that aren’t visible on the surface of an instrument like woodworm, cracks, patches and filler. Using this new technology as a diagnostic tool, a violin maker can create accurate condition reports that detail restoration work which can’t be seen by the naked eye.

Infrared imaging is cheap, accessible and provides almost all of the diagnostic information that you get from a costly scan.

Using radiography on violins isn’t new. For several decades, technical computed tomography (CT) scans have been used to create 3-dimensional high-contrast x-ray images that indicate woodworm, patches and internal repair. But CT scans can cost upwards of $3,000 per instrument and take many hours to complete. The scan facility that Tarisio uses in New York is a three-hour drive upstate. Infrared imaging is inexpensive, accessible and provides almost all the same diagnostic information that you get from an expensive scan. The instrument doesn’t need to travel, the setup can remain undisturbed and the results are available instantly.

This technology is promising, but like all data the value is in the interpretation. An experienced radiologist sees things in an x-ray that a patient doesn’t; likewise, violin makers must be trained to interpret infrared images. Just as dendrochronology aids and corroborates expertise, so too can infrared imagery support and verify what a violin maker or an expert sees with his or her eyes. You won’t find infrared photographs in our auction catalogs, but the technology is already assisting the violin makers who prepare our condition reports in New York, London and Berlin.

Explaining and documenting an instrument’s condition with customers is essential to a healthy marketplace. For Tarisio this technology is a game changer: it will provide new insight into the instruments we’re selling; it will make our condition reports more accurate; and it will give clients even more reason to trust us and to buy with confidence.

Photo: Leonhard Rank