‘The violin art of the sisters Adila and Jelly is well known here. They have such different peculiarities that they make their concert most interesting,’ wrote a critic in 1913. ‘Here the stormy gymnast with the temperament of a gypsy, there the clarified one, ready for the most beautiful and most exalted tasks, characteristics that already deviate from the ordinary… At the piano sat the third sister Hortense, who as an accompanist demonstrated solid ability and pianistic swing.’ [1]

The Sisters d’Aranyi were all exceptionally gifted artists. They were born in Budapest – Adila in 1886, [2] Hortense in 1887 and Jelly in 1893 [3] – into a noble Hungarian family, where father Taksony, the Chief of Police, and mother Adrienne Nievarovich de Ligenza saw the talent of their daughters blossom through the years alongside their international fame. They shared a passion for music and a deep affection for each other despite their different personalities. This feature explores the careers of the two violinists, Adila and Jelly.

The three sisters, from left to right: Hortense, Adila and Jelly

Adila has often been described as exuberant, impulsive, but also warm-hearted. She was already performing in public by 1900, although some early articles mention her erroneously under her mother’s name: [4] ‘The public listened with astonishment to Arànyi Adrienne [sic], the police commissioner’s thirteen-year-old daughter, playing with great artistic precision and impeccable technique Bériot’s Scènes de Ballet. Arànyi has a definite personality; and one day, in fact very soon, will create a sensation with her beautiful playing.’ [5] The sisters were great-nieces of the renowned Joseph Joachim and Adila enrolled at the Budapest Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music, where she studied the violin under Joachim’s former pupil, Jenő Hubay.

Adila passed her Artist’s Diploma exam in 1906 and was also presented with a Balestrieri violin of 1736 from her teachers. [6] At this point, Joachim, whom the sisters called Onkel Jo, offered to teach her personally and so Adila moved to Berlin, where she lived with the Joachim family for a year. She was the only pupil he ever gave private lessons.

‘[Adila] has a definite personality; and one day, in fact very soon, will create a sensation with her beautiful playing’

Her progress was so fast that Joachim planned her debut, with the Berlin Philharmonic under his direction, for the following October 1907. Unfortunately, he fell ill and died in August 1907. Adila had not only lost a dear relative, but also a vital mentor. Considering the circumstances, the fact that her debut was postponed only for a month underlines her qualities as a person as well as an artist. The debut took place on November 23 and the orchestra was directed by assistant conductor Ernst Kunwald. Adila played so well that Joachim’s heirs presented her with his 1715 Stradivari violin, thus fulfilling his wish that the instrument should be given to one of his pupils. [7]

The third d’Aranyi daughter, Jelly, began her musical career by studying the piano. On her eighth birthday she went along with her eldest sister to a violin shop in Budapest, because Adila needed to buy a bow. Once there, Jelly’s hands were noticed by her sister’s professor, Grunfeld, [8] who announced: ‘This child […] must learn the violin, not the piano.’ [9] Thus Adila spent her summer holiday teaching her sister the instrument and after just six weeks Jelly was able to master the violin so well that she was given an entrance scholarship by the Budapest Royal Academy. Apparently Joachim himself expressed the desire to teach Jelly, commenting: ‘Talent like hers […] occurs once in a century,’ [10] but her parents considered her too young to go abroad, so she was sent to the Academy to study with Grunfeld and Hubay.

Left: Jelly d’Aranyi as a child; right: the young Adila in Budapest

Jelly gave her first public concert, together with Adila, in Vienna in 1908. [11] A critic recorded: ‘The violinist Adila v. Aranyi has been known for years. This time she gave a concert with her sister Jelly, a twelve to thirteen-year-old girl who has the devil in her body. Adila is already a young lady who knows what is going on and who is therefore standing on the podium with a certain dignity. Other Jelly, a passionately forward storming girl whose violin playing represents a continuous outburst of temperament. We are told that the two sisters are grandnieces of Joachim. Well, they have inherited their violin talent and musical sense from their famous relative. Both sisters play eminently musically, feel well-founded, avoid every little trick, have a warm, round tone, master the whole passage technique and show a dexterity in bowing that is rarely observed.’ [12]

Indeed Jelly’s style and temperament were often described as ‘gipsy’ or ‘devilish’. One critic wrote: ‘There is something overwhelming in her playing that seems to be independent of notes, trills and neck-breaking violin pieces; as I already mentioned: “The devil lies in her body,” who carries everything away with him.’ [13]

The three sisters performed together in Austria, Maribor (Slovenia) and Italy in 1908 and then moved to conquer England, where they became the protégés of Donald Francis Tovey, who often accompanied their performances on the piano. Their London debut took place at Wigmore Hall on June 8, 1909 and soon English society grew fond of them.

‘Their playing was a remarkable example of absolute cohesion and mutual sympathy and understanding in the minutest detail’

At the outbreak of World War I the sisters were living in England and decided to remain there. Jelly had by then made a name for herself: ‘When will the musical public awake to the fact that in Miss Jelly d’Aranyi we have in our midst one of the very greatest of living women violinists – perhaps the greatest of all? […] She is standing head and shoulders above nearly all her contemporaries, even those possessed of the highest names.’ [14] But it should not be forgotten how magnificently Adila and Jelly played together: ‘Their ensemble is so perfect that no disparity of style is observable, but individually Adila in accordance with her nature and training leans to the purely classical school and her playing is sound, scholarly, and refined, but not inspirational. Jelly on the contrary has almost an excess of temperament and a warm vivid style which rings true… Still, it is in their combined work that the sisters Von Aranyi are heard to the greatest advantage, and in this respect they occupy quite a unique position.’ [15]

Years later, one critic commented: ‘Their playing was a remarkable example of absolute cohesion and mutual sympathy and understanding in the minutest detail. The result in tone, interpretation and harmony was surprising and soul-stirring.’ [16] As Tovey recorded in his diary, they were ‘in love with everyone and everyone with them.’ [17]

In November 1915 Adila married the barrister Alexander Fachiri. It has been speculated that Jelly would have married Frederick Septimus Kelly, a composer, pianist and Olympic rowing champion, if he had not been killed in the Battle of Somme in 1916. There is no firm proof of a romance between them, but Jelly never married and kept a drawing of him on her piano for her entire life. A few years ago Christopher Latham, former director of the Canberra International Music Festival, recovered a Violin Sonata in G major for Jelly that Kelly committed to paper on his way home from Gallipoli.

Left: photo of Adila with an inscription dated 1931; photo: private collection of the family. Right: inscribed photo of Jelly dated 1933

In fact, several composers dedicated their works to Jelly. Bartók, who was an old friend of the family, wrote two violin sonatas for her. Vaughan Williams wrote a Concerto Accademico (1924–25) and Ethel Smyth a Concerto for Violin and Horn (1928) for her, while Holst dedicated his Double Concerto for Two Violins and Orchestra (1929) to Adila and Jelly. [18] But as a dedicatee, Jelly is mostly connected with Ravel’s Tzigane (1924). Ravel met her in London in June 1922, when she apparently played gypsy melodies for him until 5 am. The composer promised to write a work for her, and he seems to have begun it soon after his return to Montfort. [19] This first draft remained unfinished until Jelly and Bartók reminded Ravel of his promise at a joint dinner in summer 1923. The premiere took place at the Aeolian Hall in London on April 26, 1924. Jelly received the music just ‘three and a half days before’ and the fact that she mastered it testifies to her great artistic capability. [20]

Jelly’s most successful period was before World War II, when she performed all over Europe, sometimes with her sisters. She had various accompanists, one of them being Myra Hess, but her favourite was probably Ethel Hobday, who was also responsible for her change of violin. Jelly’s instrument was a Bergonzi, but in 1937 Hobday started a subscription to present her with a Stradivari, the 1710 ‘Lord Dunraven’. This reached £1,400, which amounted to half of the price of the violin, so Jelly paid the difference commenting that ‘she had bought the body of the Strad and her friends and admirers its soul.’ [21] She presented her Bergonzi to her niece, Adrienne (Adila’s daughter), on her 15th birthday.

The 1710 ‘Lord Dunraven’ Stradivari, which Jelly played from 1937 thanks to an early example of crowdfunding. Photos: courtesy Bein & Fushi Inc

More photosIn 1933 Jelly had an extraordinary coup: she uncovered Schumann’s Violin Concerto in D minor after taking part in a then-popular activity, the Ouija board. [22] Apparently during a séance the spirit of Schumann urged Jelly to look for his violin concerto, which he had written in 1853 but had long been considered lost. Claiming never to have heard of it before, Jelly went in search of the manuscript. Through a series of séances that involved Adila and the Swedish diplomat and close friend of the Fachiris, Erik Palmstierna, [23] and thanks to the support of several people, including Wilhelm Strecker, head of the publishers Schott Music, the manuscript was eventually uncovered in the Prussian State Library.

It seems that Joachim, Brahms and Clara Schumann had decided not to make this late work public because they considered it inferior. Joachim, to whom Clara had given the manuscript, stipulated that it was not to be published or performed within a hundred years of Schumann’s death. After Joachim’s death his family sold the manuscript – among other papers – to the Prussian State Library in Berlin, where it remained undisturbed until Jelly began to look for it.

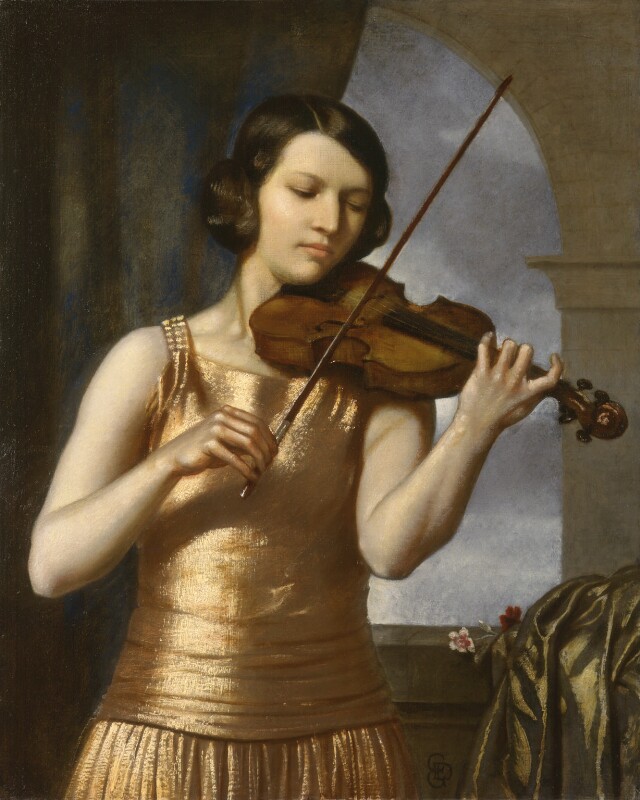

Portrait of Jelly d’Aranyi by Charles Geoffroy-Dechaume, 1920s. Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London

As soon as it had officially been uncovered, a struggle began to host the world premiere. Schott Music sent a copy of the manuscript to Yehudi Menuhin, who wrote excitedly to a friend in 1937: ‘This concerto is the historically missing link for the violin literature; it is the bridge between the Beethoven and the Brahms concertos, though leaning more towards Brahms.’ [24] Jelly agreed to let Menuhin give the first performance in the US if she could perform the UK premiere. Unfortunately for them both, the publication rights for the work were in Germany, then under the Nazi regime, and the world premiere was awarded to Georg Kulenkampff, who performed it in Berlin on November 26, 1937. Menuhin played it for the first time at Carnegie Hall in New York on December 6, while Jelly gave the UK premiere with the BBC Symphony Orchestra directed by Sir Adrian Boult at Queen’s Hall on February 16, 1938.

The reaction of critics was lukewarm. ‘Gamba’ commented in The Strad: ‘… historically, at any rate, this was perhaps the most interesting event of the present season. It was not surprising that there was some disappointment, although those who had faith in the judgment of Joachim and Brahms could not really have expected to hear a master-work. I hear that Miss d’Aranyi played with all her forceful eloquence and personal quality of style.’ [25]

Adila d’Aranyi, whose husband died in 1939. Photo: private collection of the family

In 1939 Adila’s husband died, followed a year later by their friend Tovey. Adila’s response to these losses appears to have been to keep herself busy. She had always dedicated more time and energy to teaching than Jelly, [26] and now she increased the number of her performances. By contrast, Jelly seems to have lost part of her fire. At the end of 1944 a critic commented: ‘Miss Jelly d’Aranyi has made few appearances lately compared with her former activity. Her recital at Wigmore Hall on November 11 was somewhat in the nature of a return… One of the first essentials in violin playing, however, is correct intonation, and the lapses in this respect were so serious as to nullify the other virtues of the performance.’ [27]

Adila (left) and Jelly after their move to Bellosguardo, Florence, in the 1950s. The sisters lived there together until Adila’s death in 1962

Hortense d’Aranyi died in 1953, and a couple of years later Adila and Jelly moved to Florence. Occasionally the sisters gave concerts, sometimes together. These were rare occasions in which a lucky audience could still hear them sparkle: ‘It was a great pleasure to hear Adila Fachiri and Jelly d’Aranyi again after their long absence… The readings were remarkable for their blending of warmth and dignity and for the perfect mutual understanding that is apparent between the exceptional sister artists.’ [28]

Adila died ‘in her sister’s arms’ on December 15, 1962. [29] ‘After Adila’s death some people thought that Jelly seemed hardly to care much about this world. Adila had replaced her mother, and on both Jelly had depended in the same way.’ [30] Nevertheless, Jelly still gave concerts for friends. Her sister’s place by her side on stage was then taken by Adila’s daughter, Adrienne. Jelly died on March 30, 1966, the last of the sisters d’Aranyi, who remain unforgotten in the music world.

With thanks to Jane Camilloni, Roberto Regazzi and the Arcanum Database.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an Italian art historian and has authored several books including the four-volume ‘Antonius Stradivarius’.

Notes

[1] ‘Violin Concerto of the Sisters Aranyi’, Freie Stimmen, Klagenfurt, February 11, 1913, p. 4.

[2] Adila’s date of birth often appears incorrectly, for instance in her obituary in The Strad, London, February 1963, p. 381.

[3] Jelly’s date of birth has also been incorrectly recorded, for instance in her obituary in The Strad, London, May 1966, p. 25.

[4] ‘Concerts’, Magyarország, August 09, 1900, p. 8. Adila is here wrongly referred to as ‘Adrienne’.

[5] ‘Concert in Crikvenica’, Budapesti Hirlap, Budapest, August 11, 1900, p. 8. Adila’s sister, Hortense, took also part at the event playing a ‘Rondo on piano’.

[6] Macleod, Joseph, The Sisters d’Aranyi, Allen and Unwin, London, 1969, p. 45.

[7] Neue Freie Presse, Vienna, November 29, 1907, p. 15.

[8] Frank Thistleton mistakenly records that it was Hubay who noticed Jelly’s hands, ‘Jelly d’Aranyi’, The Strad, London, September 1926, p. 269.

[9] Macleod, J., Op. cit., p. 46.

[10] Ibid., p. 48.

[11] Neues Wiener Tagblatt, Vienna, October 22, 1908, p. 16.

[12] RP, Neues Wiener Tagblatt, Vienna, November 12, 1908, p. 62.

[13] Hilbrand, Aug., ‘Concert’, Freie Stimmen, Klagenfurt, February 6, 1909, p. 8.

[14] Westminster Gazette, London, October 27, 1919.

[15] Henderson, B., The Strad, London, August 1912, p. 140.

[16] Thatcher, E. C. ,‘Music in Blackpool’, The Strad, London, February 1930, p. 526.

[17] Macleod, J., Op. cit., p. 65.

[18] Adila was also the dedicatee of Rebecca Clarke’s Midsummer Moon.

[19] Stegemann, Michael, Maurice Ravel, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1996, p. 113.

[20] Macleod, J., Op. cit., p. 146.

[21] Ibid., p. 48.

[22] Ibid., pp. 186–203.

[23] Palmstierna, Erik, Horizons of Immortality. A Quest for Reality, Constable & Co., London, 1937.

[24] Magidoff, Robert, Yehudi Menuhin, The Story of the Man and the Musician, Doubleday, New York, 1955 (German edition, Herbig Verlag, 1980, p. 190).

[25] Gamba, ‘Violinists at Home and Abroad’, The Strad, London, March 1938, p. 485.

[26] Among others, the two sisters taught Eve Fleming, mother of the famous cellist Amaryllis Fleming.

[27] The Strad, London, December 1944, p. 172.

[28] The Strad, London, July 1960, p. 93.

[29] Macleod, J., Op. cit., p. 265.

[30] Ibid., p. 284.