‘I have, I don’t know why, my own antipathy to see a woman with a violin, perhaps because I love only the round shapes of a woman, and playing the violin brings out all the angular ones,’ so began a typically misogynistic review of a concert by Teresa Ottavio, a pupil of Paganini, in 1835. [1] Little did the critic know that just a few years later another violinist with the same forename was going to conquer the hearts of audiences across Europe: Teresa Milanollo.

Through her career Teresa Milanollo was to break an invisible wall and slowly but surely make it possible for female violinists to be perceived as real artists. The music author Henry Charles Lahee summarized her importance: ‘There is little doubt that the success of Teresa Milanollo gave the first great impulse toward the study of the violin by women.’ [2]

Teresa Milanollo in 1841, by Marie-Alexandre Alophe. Image: Gallica Digital Library via Wikimedia Commons

Teresa Milanollo was born in Savigliano, a small Italian town some 30 miles from Turin, in 1827. She was the daughter of Carlo Giuseppe Milanollo and Antonina Rizzo. Little is known about her family, and her father’s profession was the subject of much speculation. Some articles described him as silk-weaver or manufacturer of silk spinning machines, others as violin maker, [3] while according to the musicologist Fétis he was a poor carpenter with 13 children. [4] In fact, there were only ten children, but the family was needy indeed.

Teresa began to play the violin by accident or, perhaps better to say, thanks to her determination. As the legend goes, she was about only four when she first heard a violin while attending mass. The music thrilled her so much that she decided to learn how to play it. Her parents tried to dissuade her but to no avail. Her father eventually found a music teacher for her, Giovanni Ferrero, ‘a boy of 14 years’. [5]

Soon enough it became clear that Teresa was extremely talented. Hoping to have found a way to make ends meet, the family moved to Turin to allow the six-year-old to continue studying the violin. It is unclear exactly who taught Teresa at this stage, as Mauro Caldera, Giovanni Morro [6] and Paolo Giuseppe Ghebart have all been cited as her teachers. She progressed so rapidly that she was already performing locally by 1836. One critic reported: ‘In Savigliano there is a true prodigy of nature. Mrs. Teresa Milanollo, aged seven, [7] plays the violin in an admirable way for her age.’ [8]

The Francesco Rugeri violin owned by Maria Milanollo; sold by Tarisio in 2010. Photos: Tarisio

More photosThese first concerts brought more enthusiasm than cash, but they convinced her father to set off with his gifted daughter for Paris. Since they could not afford a carriage, the Milanollos travelled across the Alps on foot. It is difficult to imagine how exhausted they must have been when they finally reached France several months later. Teresa surely understood by then that the fortunes of her family lay on her small shoulders. With no time to rest, she gave several concerts in Marseille and earned enough money to proceed to Paris. There she became a pupil of Charles Lafont, who was so impressed by her talent that he invited her to tour with him through Belgium and The Netherlands and share the proceeds.

But several months of relentless activity took a heavy toll on the child, who fell so ill in Amsterdam that the tour was cancelled. As soon as she recovered, she was summoned to play to the Prince of Orange and gave several concerts in The Hague before embarking for the UK. Here, the harpist Nicolas-Charles Bochsa acted as her manager. The two played together in several towns, often twice a day, reaching a total of more than 40 concerts in a month, an extraordinary undertaking for a child of ten! Unfortunately Bochsa apparently then fled with the proceeds. [9]

After more than a year and a half, the Milanollos returned to France, with Teresa performing non-stop on their journey to Paris. But this time she was not alone: her younger sister Maria joined her on the stage.

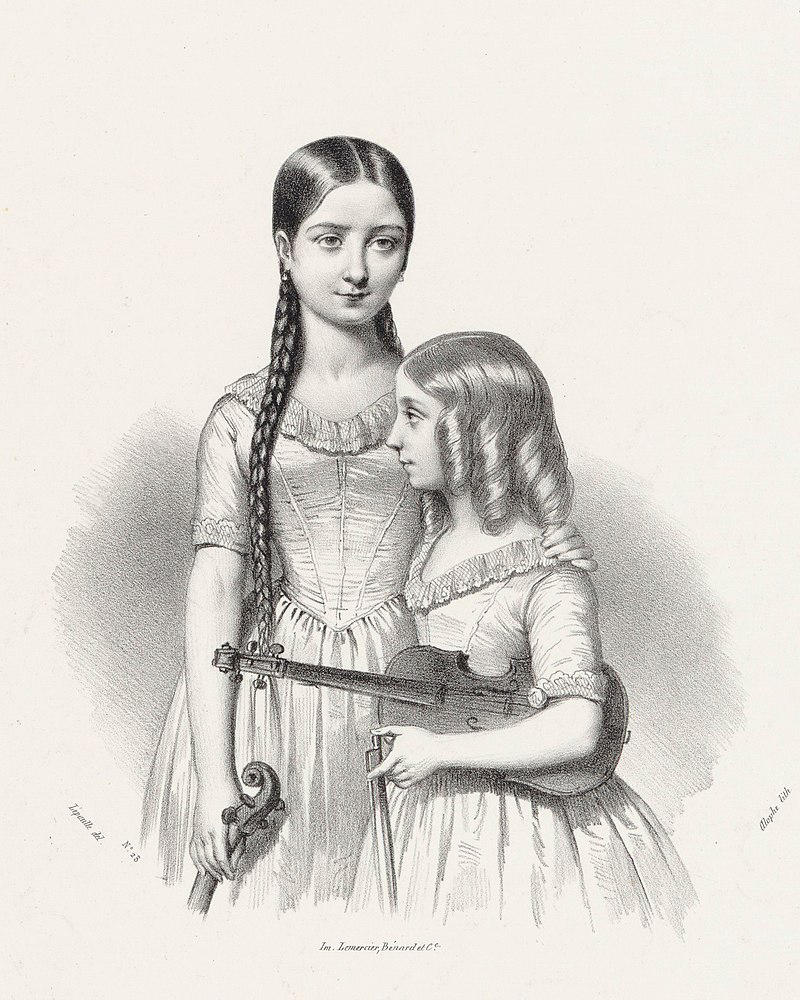

Teresa and Maria Milanollo in 1841, by Marie-Alexandre Alophe. Image: Gallica Digital Library via Wikimedia Commons

Maria Milanollo was born in June 1832 and was only six when the two sisters began to perform publicly in 1838. [10] Maria’s appearances at the side of her sister were initially sporadic, but by 1840 she was a permanent presence on stage. The sisters provoked an almost religious reverence in some critics: ‘One was prepared for bravura, for technique, for miracles; but here was art in its most sacred transfiguration, here the heavenly music spoke in celestial tones; I would have liked to listen eternally, endlessly, to immerse myself in the sea of harmony, dissolved in melancholy and rapture. […] The Milanollos are the most remarkable phenomena in the music world since time immemorial.’ [11]

In Paris Teresa became a pupil of François Habeneck, professor of the Paris Conservatoire. Habeneck wanted her to perform at the conservatoire, but the board, which was composed of distinguished musicians including Cherubini, Carafa, Auber and Adam, did not share his enthusiasm. [12] They agreed to let her play but omitted her name from the printed program, in the hope that Habeneck would reconsider. On the day of the rehearsal, someone did change their mind, but it was not Teresa’s teacher. As soon as she completed the first solo of Habeneck’s Polonaise, the orchestra members all left their seats to congratulate her, and Auber, who had been her strongest opponent, demanded that new labels bearing her name be printed for the program immediately. [13]

Lithograph of Teresa (left) and Maria Milanollo by Josef Kriehuber. Image: Gallica Digital Library via Wikimedia Commons

The concert itself was a huge success. Hector Berlioz reviewed it in glowing terms: ‘Here it comes, mademoiselle Térésa Milanollo, […] she takes a violin, a big one like Artôt’s, and plays a great fantasy with a large orchestra, […] she draws great sounds from it with great accuracy, and after a few bars she raises a great storm of applause. It’s obvious that this child is already capable of great things. It is not to be believed that this enormous success is only due to the remarkable precocity of her talent. No, the charm felt by the audience was very real, very musical.’ [14]

Teresa was by now so famous that she and her sister were summoned to play to King Louis Philippe. In 1841 she became a pupil of de Bériot and through him acquired a profound knowledge of the Franco–Belgian school, which became an essential part of her repertoire. In the summer of 1842 the sisters proceeded to give no fewer than 90 concerts in Germany in a tour that ‘resembled a triumphal procession.’ [15]

‘I only talk Milanollo, I only think Milanollo, I only breathe Milanollo. I’ll travel after them, I’ll become their servant, their slave, their rosin…’

They then moved to Vienna where, having been treated to celebrities such as Vieuxtemps, the audience was rather sated. Nevertheless, the Viennese were overwhelmed by the sisters, who gave nine concerts in rapid succession. One critic raved: ‘I only talk Milanollo, I only think Milanollo, I only breathe Milanollo. I’ll travel after them, I’ll become their servant, their slave, their rosin – whatever they want me to be, just to be near them.’ [16]

As a result of the sisters’ different musical styles, they were nicknamed Mademoiselle Adagio (Teresa) and Mademoiselle Staccato (Maria). [17] Nevertheless, Teresa was clearly the superior performer. One critic wrote: ‘Certainly Maria Milanollo is a musical phenomenon, but she is just a delicious toy, a counterfeit, a nice imitation of Teresa Milanollo, already a great artist.’ [18] Teresa meanwhile was acclaimed as ‘prima donna assoluta on the violin’ [19] and counted among her fans Joseph Joachim, who never failed ‘to call upon her when on a visit to the French capital.’ [20]

Teresa (left) and Maria photographed in 1848, the year of Maria’s death. Photo: Gallica Digital Library

But in 1848 tragedy struck: Maria fell ill and died of consumption that October, aged only 16. Devastated, Teresa seriously thought of becoming a nun, but her family managed to dissuade her. [21] She was back on the stage by the beginning of the 1850s. When Maria was still alive the sisters had regularly held concerts for charity purposes; now Teresa extended this project, which would become known as Concerts aux Pauvres, to support widows, orphans and the poor of all descriptions.

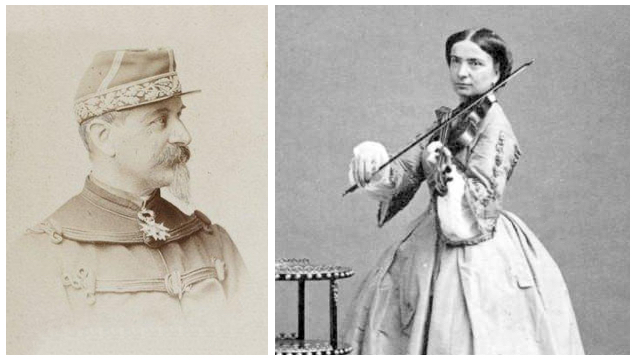

Teresa’s career came to an end a few years later, in April 1857, when she married General Théodore Parmentier. Following the custom of the time, she ceased to perform publicly apart from occasional charity concerts. She had found in Parmentier a new ally, who shared her passion for music and was an enthusiastic composer and a regular contributor to the Gazette Musicale. [22]

Left: Joseph Charles Théodore Parmentier; photo: Wikimedia Commons; right: Teresa Milanollo photographed by Disdéri in 1862, a few years after their marriage; photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France via Wikimedia Commons

Teresa died in Paris on October 25, 1904. Despite her later wealth, she never forgot the poverty of her childhood and bequeathed 90,000 francs each to the conservatories in Paris and Milan to support disadvantaged students. [23] She also left money to the Association des Artistes Musiciens in Paris. [24]

The Milanollo sisters inspired composers including Theodore Oesten (Souvenir de Milanollo) and Carl Czerny (Souvenir des Soeurs Milanollo), as well as authors Adalbert Stifter (The Sisters) and Theodor Fontane (Frau Jenny Treibel). They were ‘often thought to be the first pair of violin duettists in history,’ [25] and Teresa especially will be remembered as the child ‘who… was able to thrill audiences fresh from hearing Paganini, Spohr, and De Beriot, and who could rival such masters as Ernst and Vieuxtemps in their prime.’ [26]

Original French, German, and Italian texts translated by Alessandra Barabaschi. Thanks to Roberto Regazzi for assistance with archive material.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an Italian art historian and has authored several books including the four-volume ‘Antonius Stradivarius’.

The Milanollo instruments

According to Berlioz, Teresa Milanollo was already playing a major instrument for her 1841 concert at the Paris Conservatoire. [27] This may have been the violin that, according to a contemporary article, ‘the rich Cuisinier in Paris’ presented her with, together with a bow that had belonged to her former teacher Lafont. [28] Cuisinier owned the ‘Adam, Mischakoff’ Stradivari of 1714.

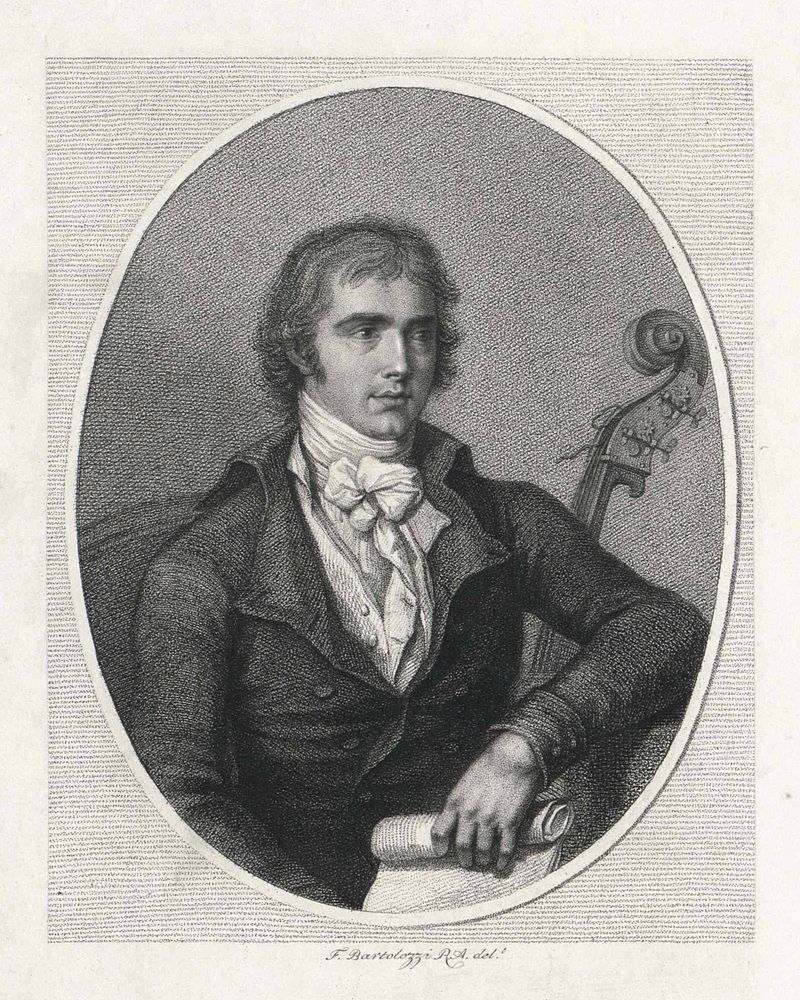

What’s certain is that Teresa owned at least one other Stradivari, the 1728 ‘Dragonetti, Milanollo’. This was bequeathed to her by the double bass virtuoso Domenico Dragonetti. The story around this instrument was told by Teresa’s mother to the opera director Ernst Pasqué in 1854. [29]

The ‘Dragonetti, Milanollo’ Stradivari. Photos: courtesy Jan Röhrmann

Dragonetti had bought the violin from Paganini, who in turn had received it as a gift from a wealthy English lord (there seems to be no record of his name). Apparently one of the lord’s ancestors had bought it in Cremona from Stradivari himself and it had been kept in the family ever since. Paganini was fascinated by this violin and the lord, who was in turn fascinated by Paganini, presented it to him on the condition that he would only play it in England. Paganini kept his word, but later sold the violin to Dragonetti, who often said that this instrument should go back to Italy after his death.

When the Milanollo sisters were in London they visited their compatriot and often played this instrument for his delight. After his death in 1846, they were informed that he had bequeathed the Stradivari to Teresa and another valuable instrument to Maria. According to her mother, Teresa usually kept this violin in reserve because ‘strange things happened to it.’ One day during Maria’s illness she felt better for a moment and asked Teresa to play for her on the Stradivari. No sooner had Teresa finished than suddenly two strings broke. Worried that this could be a bad omen, Teresa put the instrument away. Maria died the following day.

Engraving of Domenico Dragonetti with his Gasparo ‘da Salò’ bass, by Francesco Bartolozzi. Image: Wikimedia Commons

After Teresa’s death, the instrument was sold by the Hills to a Mr Ratnagar of Bombay. [30] It returned to Europe in 1967 and was purchased by Christian Ferras, who kept it until his death in 1982. Around 1990 the violin was bought by Pierre Amoyal in the interlude when his ‘Kochanski’ Strad had been stolen; it has also been played by Corey Cerovsek.

Teresa owned another violin that has been attributed to Stradivari, the ‘Milanollo, Hembert’, which her father bought from the French violin maker Nicolas Darche in 1841. She was also presented with a fine gold-mounted Dominique Peccatte by the Lyon Musical Society in 1846 [31] and owned a silver-mounted François Xavier Tourte engraved with her name.

The instrument Dragonetti bequeathed to Maria, according to his last testament, was by Gasparo ‘da Salò’; however, it is unclear what happened to this violin. Maria also owned a violin which at the time was considered to have been made by the Brothers Amati, [32] but has since been attributed to Francesco Rugeri, c. 1680. It was sold by Tarisio in 2010. [33]

Notes

[1] Castelli, Ignaz Franz, ‘Notizen’ in: Allgemeiner Musikalischer Anzeiger, Vienna, no. 47, November 19, 1835, p. 188.

[2] Lahee, Henry Charles, Famous Violinists of to-Day and Yesterday, L. C. Page, Boston, 1899, reprint 1906, p. 313.

[3] ‘Die Schwestern Milanollo’ in: Illustrierte Zeitung, Leipzig, N. 13, September 23, 1843, p. 201; ‘Theresa Milanollo’ in: Sonntags-Blätter, Vienna, N. 19, May 7, 1843, p. 451; ‘Teresa Milanollo’ in: Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode, Vienna, no. 56, April 8, 1841, p. 446; Blanchard, Henri, ‘Concerts’ in: Revue et Gazette Musicale, Paris, no. 28, April 11, 1841, p. 222; Athanasius, ‘Therese und Marie Milanollo’ in: Allgemeine Wiener Musik-Zeitung, Vienna, no. 56, May 11, 1843, p. 233.

[4] Fétis, François-Joseph, Biographie Universelle des Musiciens, Librairie De Firmin Didot Frères, Fils et Co., Paris, 2nd edition, vol. 6, 1864, p. 139.

[5] Rellstab, Ludwig, ‘Therese Milanollo’ in: Neue Berliner Musikzeitung, Berlin, no. 14, April 20, 1853, p. 108.

[6] Ehrlich, Arthur, Berühmte Geiger der Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, Albert H. Payne Verlag, Leipzig, 1893, p. 135. Ehrlich recorded his name as ‘Morra’. Also, Fétis, F-J, op. cit., p. 139. Fétis recorded his name as ‘Mora’.

[7] Teresa was in fact nine at the time. The newspapers often gave younger ages for the sisters at the beginning of their career.

[8] ‘Notizie diverse’ in: Il Pirata, Milan, N.92, May 17, 1836, p. 368.

[9] Fétis, F-J, op. cit., p. 140. Also: Stookes, Sacha, ‘Teresa Milanollo: 1827–1904’ in: The Strad, London, January 1955, p. 308.

[10] Athanasius, op. cit., p. 234.

[11] ‘Concert der Schwestern Milanollo’ in: Der Wanderer, Vienna, no. 97, April 24, 1843, pp. 387–388.

[12] ‘Allerlei – Therese Milanollo’ in: Fremden-Blatt, Vienna, N. 79, April 2, 1853.

[13] Rellstab, Ludwig, ‘Therese Milanollo’ in: Neue Berliner Musikzeitung, Berlin, no. 15, April 30, 1853, p. 116.

[14] Berlioz, Hector, ‘Dernier Concert du Conservatoire‘ in: Revue et Gazette Musicale, Paris, no. 30, April 25, 1841, p. 235.

[15] ‘Die Schwestern Milanollo’, September 23, 1843, op. cit. p. 201.

[16] Paulinger, Peter, ‘Offenes Schreiben aus Grätz’ in: Der Wanderer, Vienna, N. 188, August 9, 1843, p. 752.

[17] Lahee, H. C., op. cit., p. 310.

[18] Blanchard, H., op. cit., p. 223.

[19] Kunt, Carl, ‘Teresa und Maria Milanollo’ in: Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode, Vienna, N. 87, May 2, 1843, p. 694.

[20] Moser, Andreas, Joseph Joachim – A Biography, Philip Wellby, London, 1901, p. 24.

[21] ‘Allerlei – Therese Milanollo’, op. cit.

[22] ‘Nouvelles Diverses’ in: Revue et Gazette Musicale, Paris, no. 2, January 9, 1870, p. 14.

[23] ‘Foreign Notes – Milan’ in: The Musical Times, London, vol. 48, no. 774, August 1, 1907, p. 547.

[24] Milanollo entry, Sophie Drinker Institut website. Accessed January 1, 2020.

[25] ‘Violinists at Home’ in: The Strad, London, December 1904, p. 230.

[26] Stookes, S., op. cit., p. 310.

[27] Berlioz, H., op. cit., p. 235.

[28] Athanasius, op. cit., p. 234.

[29] Pasque, Ernst, ‘Die Violine der Therese Milanollo’ in: Neue Berliner Musikzeitung, Berlin, no. 1, January 4, 1854, pp. 5-6.

[30] Lebet, Claude, L‘âge d‘or du violon. De Gouden eeuw van de viool, catalog of the exhibition held at the Hôtel de ville, Brussels, March 1–5, 2000, Les Amis de la Musique, Spa, 2000, pp. 8-9. Also: Hargrave, Roger, ‘Stradivari perfectly preserved’ in: The Strad, June 2004, p. 617

[31] Lebet, Claude, Les deux Stradivarius de Domenico Dragonetti, 1991, p. 30. This bow is probably the one featured as ‘ex Milanollo’ in Childs, Paul, The Bowmakers of the Peccatte Family, Magic Bow Publications, New York, 1996, p. 99.

[32] ‘Sotheby’s Sale’ in: The Strad, September 1975, p. 391.

[33] Several newspapers reported at the time that Dragonetti left the Milanollo sisters two Stradivari instruments. This appears to be incorrect: there is no evidence that a second Stradivari was bequeathed to them, and the sisters’ mother only mentioned that Maria’s violin was a ‘valuable instrument’, not a Stradivari. Other sources state that Maria’s violin from Dragonetti was the Brothers Amati (now attributed to Rugeri); however, there seems to be no documented link between Dragonetti and this instrument.