In her day, Maud Powell was acclaimed as ‘America’s greatest violinist.’ [1] She brought violin recitals to the most remote communities of her country in an almost missionary way, enthusiastically supported contemporary composers and promoted African-American spirituals. Her lifelong achievements led to the comment: ‘When others taught individuals she taught a nation.’ [2]

Her splendid example contributed to the acceptance of female professional music performers not only in the US, but around the world. She was a trailblazer on several occasions: the first American woman to form and lead a string quartet with male players (1894); first solo instrumentalist to record for the RCA Red Seal label (1904), thus becoming the first violinist to make worldwide bestselling records; and first female instrumental soloist to be awarded a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (posthumously in 2014). When asked to reveal the secret of her success, Powell answered prosaically: ‘One must have the strength of an Amazon and must work harder and longer hours than any laboring man ever dreamed of working.’ [3]

Maud Powell in 1919 at the height of her fame. Photo: courtesy of the Maud Powell Society

Born on August 22, 1867 in Peru, Illinois, young Maud absorbed the highest principles passed on to her by her parents, developing them with an almost missionary zeal in her adulthood. Her father, William Bramwell Powell, was a school superintendent whose enlightened teaching system gained him national acknowledgment, while her mother, Wilhelmina ‘Minnie’ Bengelstraeter Paul, was a talented pianist and composer with professional aspirations in a time when it was hardly conceivable for a woman to pursue a musical career.

As a result, music was part of Maud’s life from her early childhood. Her ambitious mother started to teach her the piano when she was four [4] and by the age of seven she attended piano lessons with Professor G.W. Fickensher. Half a year later she began to play the violin, but ‘disliked it exceedingly’ until ‘after six months […] of dutiful but irksome scraping’ [5] she went to a concert by Camilla Urso. From that moment, her ambition was awakened.

By the time she had reached her ninth year, Professor Fickensher felt that his pupil was in need of a better teacher and suggested to Powell’s parents the name of William Lewis of Chicago (the Powells had moved to Aurora, a city near Chicago, in 1870). Lewis agreed to teach Powell, who duly took a train every Saturday to attend her lesson, accompanied only by her violin in order to save money on the tickets. According to Powell, Lewis gave her ‘a splendid start’ and, looking back at her career, she felt that she owed most to him, ‘a born fiddler.’ [6]

Powell’s public appearances had begun as early as 1876, but it was in the 1880s that her capabilities were undoubtedly acknowledged, when Edwin A. Stein invited her to join his all-male orchestra as a first violinist. At 13 Powell was already defying conventions.

Left: Maud Powell in 1880, aged around 13. Right: in Leipzig, where she studied with Henry Schradieck from 1881–82. Photos: courtesy of the Maud Powell Society

After teaching Powell for four years, Lewis advised her parents to turn to Europe. Both he and Stein recommended the Leipzig Conservatory and Professor Henry Schradieck, [7] a highly regarded teacher who had studied with Hubert Léonard and Ferdinand David. So the Powells split: Maud, her younger brother Billy and her mother arrived in Leipzig on July 1881, while her father remained in America to support his family. After passing the entrance exam, Powell was assigned to Schradieck’s class. She must have been a particularly talented and assiduous pupil because she graduated only one year later with a first grade diploma and, with Schradieck’s blessing, left Leipzig for Paris.

Her next objective was the Paris Conservatoire. It was not an easy task, as there were 88 candidates competing for just six places in the violin classes in autumn 1882. [8] Once more, Powell showed her talent and none other than Charles Dancla was the first to congratulate his new pupil. Through Dancla’s teaching Powell learned to master not only the old French school of violin playing, but also virtuoso Italian works by Corelli and Tartini. Her teacher was impressed by her capabilities and also gave her private lessons to prepare her for the concert stage. Six months later she approached Léonard for advice on her career. He suggested that she should try performing in England for a year and Dancla agreed. [9]

‘[Powell] came to us without preliminary puff or anticipatory paragraph, and thereby she astonished us the more. She had an extraordinary masculinity of touch’ – Pall Mall Gazette, c. 1898

In the UK Powell was a sensation. She gained the respect of the critics, won the heart of the public and enchanted even the Royal Family. She performed twice at Kensington House in London before the Prince and Princess of Wales, and it was also reported that she played for Queen Victoria. [10] During this time Lady Hay arranged a meeting with Joseph Joachim who, after hearing her play, ‘urged her to go to Berlin for a year’s study with him.’ [11] Such an invitation could not be declined and so Powell moved to Berlin, adding knowledge of the Austro-German school to her already profound knowledge of the Franco-Belgian school. Like her previous teachers, Joachim found Powell to be an extremely gifted violinist and a quick learner. After only one year in Berlin, she concluded her study with a performance of Bruch’s G minor Concerto with the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Joachim himself, in March 1885. It was time now for her to go home and enjoy a well-earned success. Years later, Powell said: ‘Of my three European masters Dancla was unquestionably the greatest as a teacher.’ [12]

Powell playing the ‘Mayseder’ Guarneri. Photo: courtesy of the Maud Powell Society

During her studies in Europe Powell probably played on a violin made by George Gemünder (1869), but she came back to the US with a Pietro Guarneri chosen for her by Joachim in around 1885. [13] From 1890 she played an Amati dated 1635, which had been loaned to her. In 1903 she bought the ‘Mayseder’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ of 1732 and two years later a Giuseppe Rocca dated 1856 (also see Jason Price’s feature about the Rocca). [14] In 1907 she decided to part from the ‘Mayseder’, having purchased a violin labeled Guadagnini (now identified as an 1860 Gemünder violin), because she felt that she ‘could not play the two violins interchangeably; for they were absolutely different in size and tone-production, shape, etc.’ [15] The latter and the Rocca violin accompanied her for the rest of her life.

Maud Powell’s Gemünder violin, which was originally thought to be a G.B. Guadagnini. Photos: courtesy of the Henry Ford Museum

More photosReturning to her native country, Powell did not slow down; if anything, her tempo increased. Theodore Thomas, one of the most important conductors of his time, directed her in her first concert with the New York Philharmonic on November 14, 1885, and then engaged her as a soloist with his orchestra for a two-year tour. That was only the beginning. For the following 35 years Powell was almost constantly on the road. In 1887 she signed a three-year contract with L.M. Ruben and began a ‘Western’ tour. In Spring 1891 she toured with Patrick Gilmore and his band, while in 1892 she concerted in Austria and Germany with the New York Arion Society. In the summer of 1893 she was the only female violinist to perform with Thomas and his orchestra at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

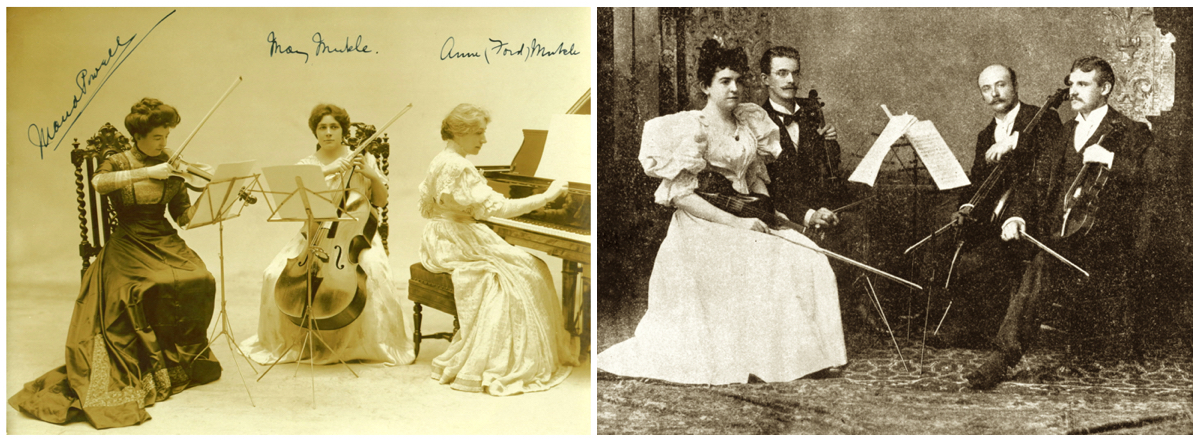

Powell with the Maud Powell Trio (left) and the Maud Powell Quartet (right). Photos: courtesy of the Maud Powell Society

Having founded the Maud Powell Quartet and toured with her male colleagues for a couple of years, she returned to Europe for another series of successes (1898–1900). In 1903 Sousa engaged her for a strenuous tour through most of Western Europe and Bohemia, Poland, Russia and Scandinavia, during which she also played for King Edward VII. [16] The following year she took a short break to marry H. Godfrey ‘Sunny’ Turner (Sousa’s English manager) in New York on September 21, 1904. But within Powell’s universe there was hardly time for personal life. And so she went on, with Sunny as her new manager, for a second season with Sousa in 1905, followed by South Africa, the US (1906–07), a season with the all-women Maud Powell Trio (1908–09, the other players being May Muckle and her sister Anne Muckle Ford), Hawaii (1912–13) and on and on.

Maud Powell sat for a portrait by Nicholas R. Brewer, who reported that at ‘every rest interval she seized her violin and played’. Photo: courtesy of the Maud Powell Society

Because Powell regarded concerting as a mission to bring music to people who otherwise would never have had the chance to hear first-class performers, she often played in small towns, at colleges and in women’s clubs for a modest fee. Despite her tight schedule, she willingly squeezed in several performances for the World War I soldiers in ‘Liberty Theatres’ (1917–18). Powell would not even take a break while sitting for her portrait, as Nicholas R. Brewer recalled: ‘With a temperament innately artistic, her sympathetic grasp of my requirements and her delightful conversation rendered the sittings a pleasure and the work a success. At every rest interval she seized her violin and played.’ [17]

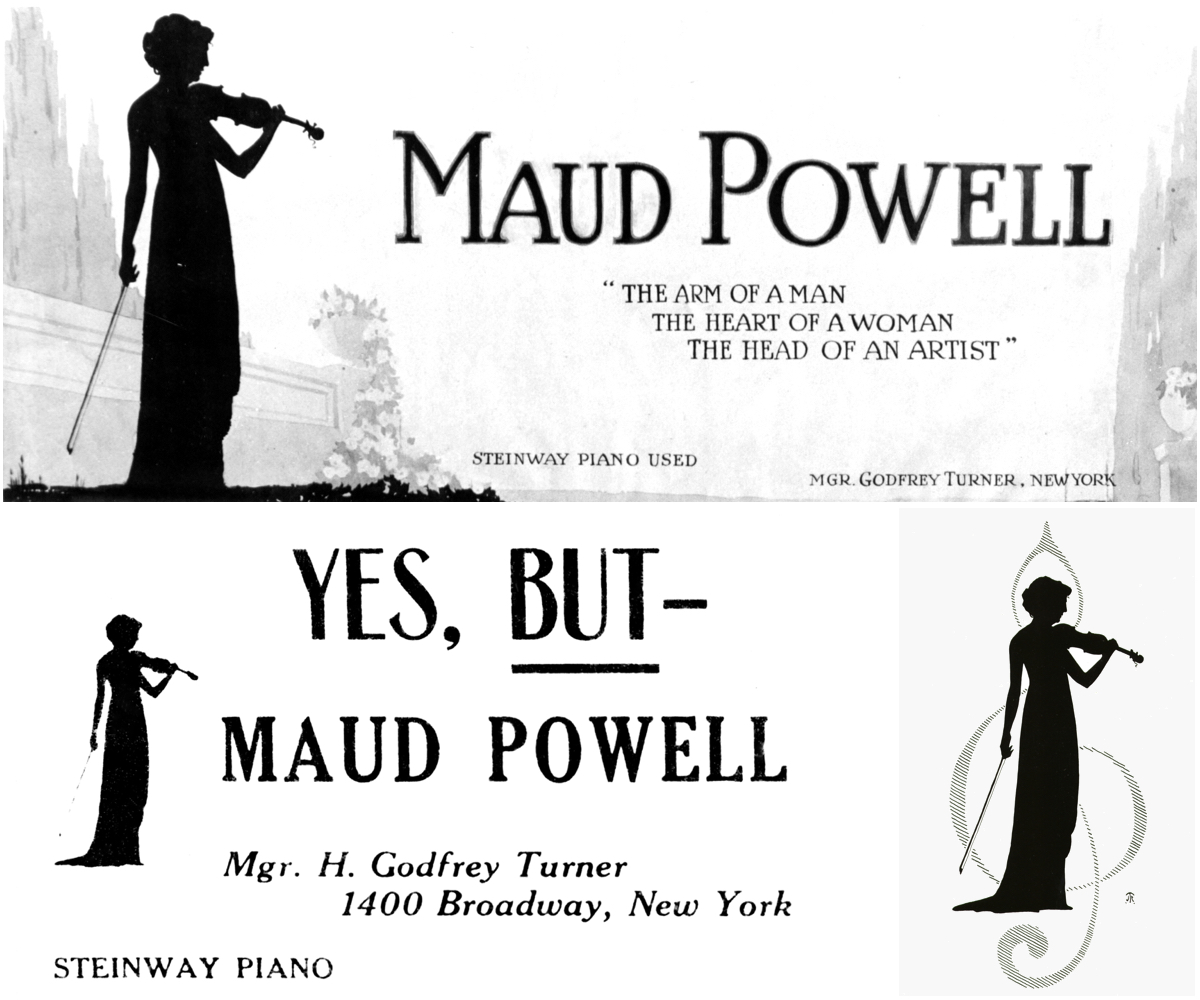

Powell became a musical icon in both the US and Europe, thanks at least in part to Sunny. She did not give up her name after marrying Sunny and he worked brilliantly on her marketing image, presenting her as a perfect combination of female and male characteristics. While praising her resolute and independent mind, he emphasized her femininity. Sunny made a logo of Powell’s silhouette and combined it with quotations from critics describing her music style. This trademark accompanied her concert programs, advertisements and stationery, and contributed to position her primarily as an artist, independent of her gender.

Powell’s manager and husband, H. Godfrey ‘Sunny’ Turner, carefully marketed her image, using a silhouette of her to create a logo (bottom right), which also appeared on advertisements for her concerts. Images: courtesy of the Maud Powell Society

This was quite a revolutionary approach to the advertising of female performers at the time. Quotations from contemporary critics reveal how much a female performer was judged in terms of her male colleagues, even those who were complimentary. One wrote: ‘Maud Powell […] belongs […] right at the top-notch of the representative list of masculine players and equal to any of them in the artistic rendition of every important classic or modern work.’ [18] And according to The Strad in 1900: ‘A brilliant and virile player, Miss Powell is invariably paid the compliment of not being judged from the standpoint of women players, but from that of excellence as musician with the technique and strength of a man.’ [19] Powell herself rebelled against this, saying: ‘The fact that I realized that my sex was against me in a way led me to be startlingly authoritative and convincing in the masculine manner when I first played. This is a mistake no woman violinist should make. And from the moment that James Huneker wrote that I “was not developing the feminine side of my work,” I determined to be just myself, and play as the spirit moved me, with no further thought of sex or sex distinctions which, in Art, after all, are secondary.’ [20]

‘A brilliant and virile player, Miss Powell is invariably paid the compliment of not being judged from the standpoint of women players’ – The Strad, 1900

While her packed agenda reveals her outstanding talent and well-deserved success, Powell paid a high price in terms of physical and mental exhaustion. Perhaps realising that she had overstrained herself, she decided to make a will on November 5, 1919. [21] A few days later, on November 27, Thanksgiving Day, she collapsed on stage right after a concert in Saint Louis. After a short rest she was back for a concert on January 7, 1920, in Uniontown. Just before going on stage, she had a second stroke and died on the following day, January 8, 1920, of an acute dilatation of the heart. [22] She was 52 years old.

With thanks to Karen Shaffer for sharing images from the Maud Powell Society.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an Italian art historian and has authored several books including the four-volume ‘Antonius Stradivarius’.

Further reading: Jason Price examines the fine Giuseppe Rocca violin played by Maud Powell.

Notes

[1] Henrici, Lois Oldham, Representative Women, The Crafters Publishers, Kansas City, MO, 1913, p. 61.

[2] Musical America, January 17, 1920, cited in Shaffer, Karen A.; Garner Greenwood, Neva, Maud Powell, pioneer American violinist, The Maud Powell Foundation, Arlington, VA, 1988, p. 419.

[3] Henrici, L. O., Op. cit., p. 66.

[4] Shaffer & Garner Greenwood, Op. cit., p. 12.

[5] Henrici, L. O., Op. cit., p. 61.

[6] Martens, Frederick H., Violin Mastery, Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York, 1919, p. 186.

[7] Shaffer & Garner Greenwood, Op. cit., p. 24.

[8] Ibid., p. 44.

[9] Maud Powell’s autobiographical sketch for Grove’s, cited in Shaffer & Garner Greenwood, Op. cit., p. 52.

[10] Shaffer & Garner Greenwood, Op. cit., p. 57.

[11] Henrici, L. O., Op. cit., p. 63.

[12] Martens, F. H., Op. cit., p. 186.

[13] Maud Powell Society website, December 9, 2018.

[14] Shaffer & Garner Greenwood, Op. cit., pp. 84, 207-13, 484.

[15] Martens, F. H., Op. cit., p. 194.

[16] Ibid., p. 195.

[17] Brewer, Nicholas R., Trails of a Paintbrush, The Christopher Publishing House, Boston, 1938, p. 249.

[18] Saenger, Gustav, The Musical Observer, New York, August 1913.

[19] B. W., ‘Miss Maud Powell’, The Strad, London, September 1900, p. 153.

[20] Martens, F. H., Op. cit., p. 191.

[21] Shaffer & Garner Greenwood, Op. cit., p. 409.

[22] Ibid., p. 414.