Leonora Jackson McKim died 50 years ago, to little fanfare in the music world. Yet during her youth she was acclaimed as a brilliant violinist. Why has her name since faded away?

Born on February 20, 1878, in Boston, MA, Jackson was often compared with her great female compatriot Maud Powell: ‘Maud Powell and Leonore Jackson are among the brightest lights from the United States,’ commented Lahee of Joseph Joachim’s numerous pupils. [1] Jackson was also credited with helping to improve the perception of American artists in Europe: ‘Leonora Jackson was the first American violinist whom European opinions recognized to equal any of its great artists and who conquered all prejudice as to the supposed inferiority of American talent.’ [2]

By her early 20s Jackson was already celebrated as a mature virtuoso: ‘Leonora Jackson is an artist her country may well be proud of, for history shows that there has never been a woman violinist of any nationality who at so early an age has been soloist of so many great symphony orchestras, played before so many crowned heads and won such a reputation in so many different countries as this distinguished, hard working young American. […] Her career has been well deserved, phenomenal.’ [3] This was quite an achievement for a woman who had succeeded against the odds.

Leonora Jackson as a child in the 1880s. Photo: McKim Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress

Leonora’s father, Charles P. Jackson, was a wealthy construction engineer who had little to do with music. Nevertheless, her musical career was decided early on – although initially she was expected to become a ‘great singer’. [4] Her mother, Elisabeth Higgins, was a singer who had dreamed of making a brilliant career. However, her vocal efforts were not crowned with success and she instead turned her ambitions to her daughter. Years later Leonora recalled: ‘She had been disappointed in her own career […], so she just naturally had to fall back on me. […] wild horses could not have stopped her, her ambition was simply immense.’ [5]

Unfortunately, Leonora disliked singing and was instead fascinated by the family piano. The instrument in question being a Steinway grand, the young child ‘was immediately requested to desist’ [6] every time she was caught tickling the ivories. Instead Leonora’s grandfather suggested she should be given a violin and by the time she was six, things were finally on the right track. [7]

The Jacksons lived in Chicago and entrusted Carl Johannes Becker with Leonora’s violin learning for four years. [8] Later she became a student of Simon E. Jacobsohn, who had served as concertmaster in Theodore Thomas’s orchestra. Encouraged by her progress, Leonora’s mother consulted Thomas regarding her prospects. Leonora did not fail to impress him: Thomas ‘pronounced her talent rare’ and advised that she should complete her studies abroad. [9]

‘Child as I was, I was suddenly confronted by poverty and the utter impossibility of continuing my studies’ – Leonora Jackson

In 1891 mother and daughter left for Paris, [10] where Jackson began studies with Léon Desjardins. [11] At the end of their first year, however, came devastating news: the entire family fortune was lost. ‘It was a great blow […],’ recalled Jackson. ‘Child as I was, I was suddenly confronted by poverty and the utter impossibility of continuing my studies. I knew I had the power to succeed, but how continue to pay for lessons and teachers? Mother knew that the position was desperate. At any price I must be sent to Europe to finish my education. We then devised the plan of giving little concerts, Brother Ernest as pianist and I as violinist, at the different seaside resorts during the summer, and with the proceeds sending me to Europe to study in the winter.’ [12]

The Jacksons in 1891: Leonora, standing, with her pianist brother, Ernest, and her mother, Elisabeth. Photo: McKim Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress

The Jackson siblings were so successful that Leonora was able to continue her study in Paris and buy a good violin, a Testore dated 1696. After two years she moved to Germany, at the suggestion of Ambroise Thomas and Charles Dancla, hoping to study with Joachim. [13] But, once in Berlin, she found that she was too young to enter the Hochschule für Musik and the great violinist did not give private lessons. Instead she was placed under the instruction of Joachim’s favorite pupil, Carl Markees. [14] It was Markees who brought her to Joachim’s attention [15] and he in turn acknowledged her qualities: ‘I have heard Miss Leonora Jackson play Vieuxtemp’s Ballade and Polonaise for the Violin, and was struck with her great talent. She played with genuine expression, and displayed a command of her instrument most unusual at her age. If she continues to study she cannot fail to become a violinist of the greatest eminence.’ [16]

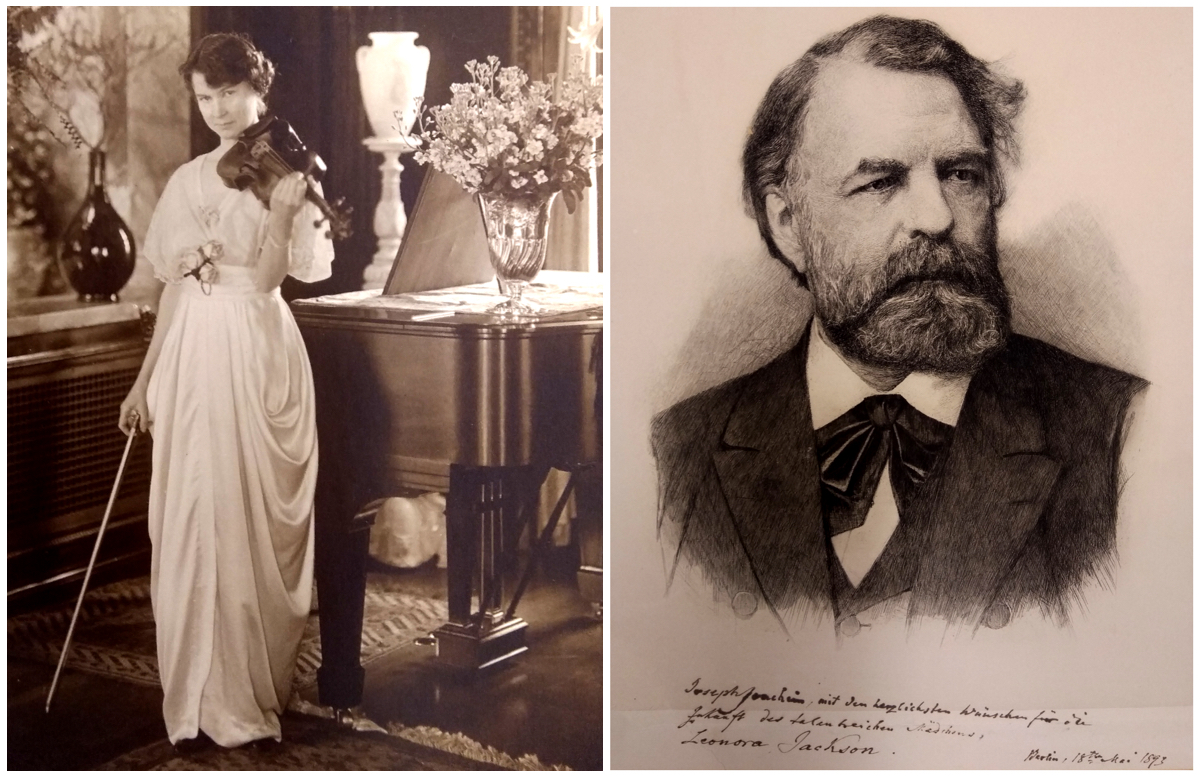

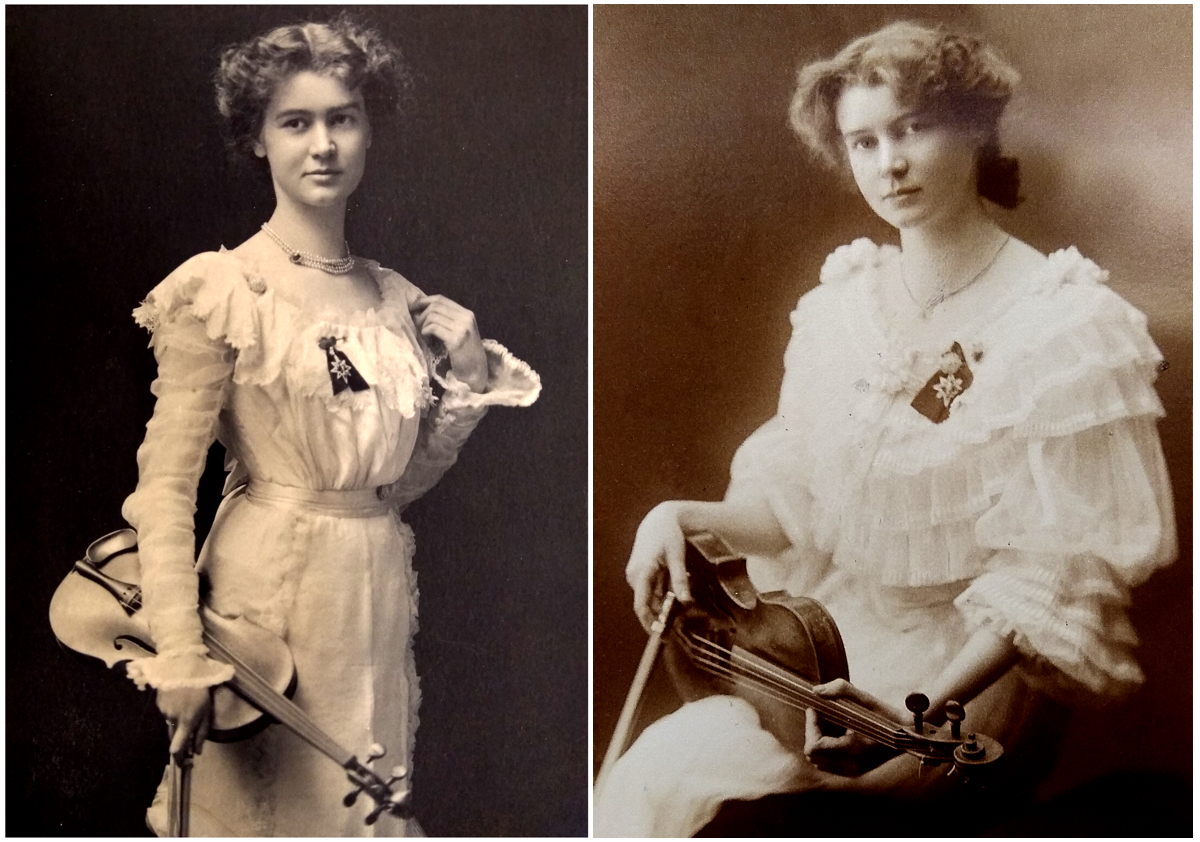

Left: Leonora Jackson pictured in the 1890s; right: a signed photo from her mentor, Joseph Joachim, dated 1893. ‘[Joachim] was the only great artist I have ever heard without mannerisms; yet he had the greatest individuality and force,’ wrote Jackson. Photos: McKim Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress

A year later, Jackson was finally allowed to attend Joachim’s private class, but her biggest obstacle was still lack of money. She gave several fundraising recitals in the US between 1893 and 1894. Public and critics were impressed by her ‘unimpeachable’ [17] technique and 20 prominent Americans, among whom were George Pullman, General Horace Porter and George Vanderbilt, together subscribed a generous sum to enable her to finish her study abroad.

Back in Berlin, both Jackson siblings entered the Hochschule. Ernest, who accompanied his sister on the piano for several years and later became her manager, was convinced that she would make a brilliant career and suggested she should keep a diary, where she recorded not only her daily activities, but also her long search for a suitable instrument. Joachim had urged her to change her violin in 1894 [18] and, with the help of her patrons, she happily noted two years later: ‘I am playing now the Storioni violin which we have exchanged for the Testore the difference being paid for by us.’ [19] The instrument in question was dated 1776 and had been valued at $3,000. [20]

Leonora Jackson in around 1900, when her career was at its peak. Photo: McKim Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress

By 1896 Jackson was ready to start her career. She made her debut in Berlin on October 17, 1896, with the Berlin Philharmonic under the direction of Joachim. Once more she was acclaimed: ‘Unquestionably we have to do here with no ordinary talent […]. From the proofs both musical and technical which the young lady offered […] she is sure of a career.’ [21] Indeed, Jackson impressed the critics despite her gender – ‘We have not for a long time heard a lady play the violin with such spirit and energy,’ wrote one [22] – and her country of origin: ‘The myth that Americans are behind the people of the Old World in depth of musical perception will be fundamentally contradicted by unusual public performances of this kind.’ [23] The following year she was awarded the prestigious Mendelssohn State Prize – a huge achievement for an American musician.

Jackson’s London debut in 1898 was another great success, and, together with a series of exhibitions that followed, made her prominent in the UK. Afterwards, she performed in various German cities, as well as in Switzerland, Belgium and Austria. Meanwhile the European Royal Houses also took an interest in her. She appeared before the German Empress in Berlin, was invited to perform for King Oscar II of Sweden and Norway, and was summoned to play before Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle on July 17, 1899. This last was one of her most exciting encounters, as Jackson recorded: ‘She was so kind and friendly – asked about my studies, about my playing in Germany and added “you play most beautifully”.’ [24] The queen presented her with a gold brooch decorated with rubies and sapphires, which Jackson wore for concerts.

Leonora Jackson in around 1900, wearing the brooch presented to her by Queen Victoria. Photos: McKim Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress

Her talent was by now acknowledged across Europe: ‘My “gentle readers” […] will soon begin to think I have lost my wits over Miss Leonora Jackson’s violin-playing, for I mean to begin these notes again this month with more eulogy of her playing,’ gushed one critic in The Strad. ‘I can’t help it, and you, gentle readers, will please bear with me. […] It is not my fault that there are so few geniuses among the myriads of fiddling ladies. Nor, fayre Ladyes […] is it your faults that you are not all geniuses. No doubt a very large number of you think that you can play quite as well as our little American cousin. But, believe an old-stager, you cannot.’ [25]

Jackson returned to the US in early 1900 after an absence of six years. Perhaps because her ‘return from Europe had been announced a number of times during the previous two years but had been repeatedly postponed because of lucrative European engagements,’ [26] a few critics froze her out. After her first appearance with the New York Philharmonic in New York on January 5, 1900, one criticized her choice to play the Brahms Concerto and outspokenly wondered about the ‘totally inexpert women who gave her a musical education.’ [27] It is of course possible that Jackson had not yet fully mastered the concerto: she also performed it with Theodore Thomas and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, after which Thomas refused to reengage her. [28]

‘My “gentle readers” will soon begin to think I have lost my wits over Miss Leonora Jackson’s violin-playing’ – ‘Gamba’ in The Strad, 1899

Despite these initial disappointments, the American public seemed not to get enough of Jackson, who was in demand in every state. During the seasons 1900–01 and 1901–02 she fulfilled over 300 US engagements, including eight appearances as soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. She gratefully acknowledged the public’s appreciation: ‘I am an American girl. I have been educated through the beneficence of the American people. Whatever triumphs I have achieved, I rejoice, since through them I have held up the Stars and the Stripes.’ [29]

The period 1906–07 brought several changes. Her beloved Storioni violin ‘cracked’ [30]; it was immediately repaired but soon afterwards she acquired a 1714 Stradivari of which she was ‘proud’ and which still carries her name. [31] But the biggest news was her marriage to Michael L. McLaughlin, a Brooklyn lawyer, [32] which was announced in 1907. [33] This effectively put an end to her musical career. The marriage did not last long, but afterwards Jackson took a sabbatical incognito for a year in Albany, NY, to recover, and never returned to the concert circuit. ‘My life has been a series of railroad journeys and hotel rooms and concert halls, a succession of cities and audiences,’ she wrote. ‘For a man such a life is exhausting; for a woman, so dependent on a home and its shelter and comfort, such a life has its drawbacks, however much the way is smoothed.’ [34]

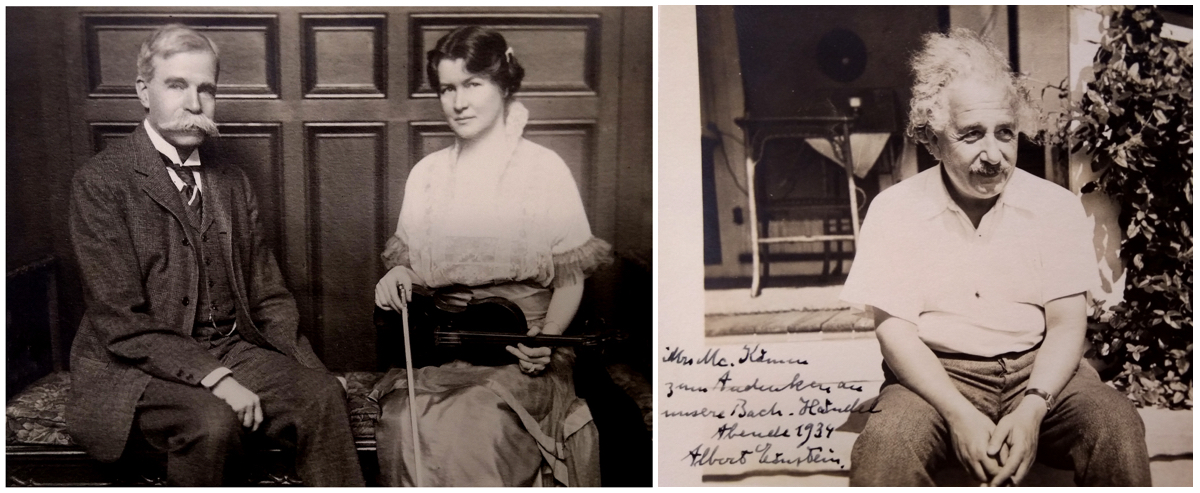

Left: Leonora Jackson and her second husband, William Duncan McKim, in 1926. Photo: McKim Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress. Right: a signed photo from the McKims’ friend, Albert Einstein, 1934

In October 1915 Jackson married William Duncan McKim of Baltimore, a successful doctor. Despite their 23-year age difference, the marriage was a happy one. The couple seem to have shared a passion for travel – they made a world tour in 1926–27 – and music. McKim was an ‘enthusiastic organist’ and had built in their Washington house a majestic organ, 36 feet high with 2,160 golden pipes. [35] Jackson was now a self-described ‘society dame’ [36] and took up painting, sculpture and writing. Although she had retired from the music scene, she occasionally gave concerts, especially charity ones, in Honolulu, where the McKims loved to reside, and their home in Washington. She had sold her Stradivari in 1919 but bought another one, the c. 1695 ‘Goetz’, in the 1930s.

The ‘Goetz’ Stradivari violin, c. 1695. Photos: Jan Röhrmann, ‘Antonius Stradivarius Vol I-IV’

More photosLeonora Jackson McKim died on January 7, 1969, almost forgotten by the music world. She, however, never forgot how generously her American patrons had supported the beginning of her career. In her will she bequeathed her personal property, valued at around $800,000, to the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, to establish the McKim Fund, supporting the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. She also bequeathed $30,000 to the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore to establish a memorial award in her name. [37]

With thanks to Carol Lynn Ward-Bamford (Library of Congress), Francis O’Neill and Micah Connor (Maryland Historical Society), John Hannigan (Massachusetts Archives), Andrew Begley (National Archives at Boston), Elizabeth Bouvier (Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court), Kelsey Kolbet and Katie Loughrey (Massachusetts Historical Society), and Roberto Regazzi for assistance with source materials.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an Italian art historian and has authored several books. She held a lecture about Leonora Jackson McKim at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., in February 2020.

The ‘Leonora Jackson’ Stradivari violin, 1714

The first known owner of the ‘Leonora Jackson’ Stradivari was the Italian violinist Giuseppe Venturini (d. 1719), who is thought to have brought it to Hanover. Here, it subsequently entered the collection of Charles II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1741–1816).

In around 1820 it was owned by an Oberbaurat (a German government official) named Hausmann. It came to Joseph Joachim around 1880, probably through his friend, the dealer August Riechers. In 1904 Joachim sold it through Lyon & Healy to the collector N.D. Hawkins of Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania.

The ‘Leonora Jackson’ Stradivari, 1714. Photos: Jan Röhrmann, ‘Antonius Stradivarius Vol I-IV’

More photosLeonora Jackson owned the violin between 1906 and 1919, when she sold it to the violin maker John Friedrich. In 1945 it was sold by Emil Herrmann to Samuel Fine of Stamford, Connecticut, for the sum of $18,000. Twenty years later the violin fetched £9,000 when auctioned by Sotheby’s in London, the purchaser being a Mr Patch. By 1972 it belonged to Alfred J. Hermanns of Akron, Ohio, and in 1984 it was sold by Bein & Fushi in Chicago to Dr William and Prof Judy Sloan of California.

Herrmann’s certificate of 1945 describes the violin’s tone as ‘outstanding’, while Robert Bein wrote in 1984: ‘I honestly don’t think there is a better sounding Strad to be had.’ [1] According to Bein, Samuel Magad, former concertmaster of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, described it as the best violin he ever played. [2]

Dr Sloan writes: ‘Having [Leonora Jackson’s] violin in our family has been a distinct pleasure. International soloists as well as devoted amateurs have enjoyed playing on it. […] The sound of the violin is sweet and full, with a characteristic rumble on the G string giving it an exciting lower register. There’s nothing like performing on an instrument which sounds like “liquid gold”.’

Notes

[1] Lahee, H.C., Famous Violinists of To-Day and Yesterday, L. C. Page, Boston, 1899, reprint 1906, p. 326.

[2] de Sayne, E., ‘A Model Music Room’, The Violinist, Chicago, vol. XXXIII, No. 5, November 1923, pp. 186–187.

[3] ‘Phenomenal Career of Leonora Jackson’, The Musical Courier, New York, Vol. XLIII, No. 13, Whole No. 1122, September 25, 1901, p. 14.

[4] Jackson McKim, L., The Memoirs of a Virtuoso, McKim Collection: Writings of Leonora Jackson McKim, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[5] Jackson McKim, L., Letter to Ernest Jackson, September 7, 1940, MS1780, Box 6, MdHS (Maryland Historical Society), Baltimore, MD.

[6] Jackson McKim, L., The Memoirs of a Virtuoso, op. cit.

[7] Graham, K., ‘An American Girl and her Violin’, Metropolitan Magazine, New York, March 1900, Vol. XI, No. 3, p. 283.

[8] Jackson McKim, L., Miss Leonora Jackson – Biographical Sketch, McKim Fund: Papers of Leonora Jackson McKim, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[9] Jackson, E.H., Career of Leonora Jackson, MS1780, Box 6, MdHS, Baltimore, MD

[10] Jackson, E.H., Personal History, McKim Collection, op. cit.

[11] Jackson McKim, L., The Memoirs of a Virtuoso, op. cit.

[12] Graham, K., ‘An American Girl and her Violin’, op. cit., p. 283.

[13] Jackson McKim, L., The Memoirs of a Virtuoso, op. cit.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Jackson McKim, L., ‘Violin Virtuoso’, MS1780, MdHS, Baltimore, MD.

[16] Joachim, J., Letter, Berlin, May 7, 1893, MS1780, MdHS, op. cit.

[17] Article in The Times, Philadelphia, January 21, 1894, quoted in Debut of Leonora Jackson in Berlin, McKim Collection, op. cit.

[18] Jackson McKim, L., Several Remarks, MS1780, Diary 1894–95, MdHS, op. cit.

[19] Jackson McKim, L., Remark 19.1.1896, MS1780, Diary 1895–97, MdHS, op. cit.

[20] ‘An enjoyable concert’, Daily Post, Houston, TX, June 31, 1901, and untitled article in News, Tacoma, WA, February 23, 1901, MS1780, Scrapbook 1900–01, MdHS, op. cit.

[21] Signale für die musikalische Welt, Leipzig, October 23, 1896, quoted in ‘Debut of Leonora Jackson in Berlin’, op. cit.

[22] Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, October 18, 1896, in ‘Debut of Leonora Jackson in Berlin’, op. cit.

[23] Berliner Neueste Nachrichten, October 21, 1896, in ‘Debut of Leonora Jackson in Berlin’, op. cit.

[24] Jackson McKim, L., Personal Words with a Queen, undated, McKim Collection, Library of Congress, op. cit.

[25] Gamba, ‘Violinists at Home’, The Strad, London, April 1899, p. 356.

[26] Ammer, C., Unsung: A History of Women in American Music, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1980, reprint by Amadeus Press, 2001, p. 48.

[27] Henderson, W.J., article in Musical Record, January 1900, referred to in: Ammer, C., op. cit., p. 48.

[28] Letter from Thomas to Fay, September 14, 1900, published in Hart, P., Orpheus in the New World, W.W. Norton & Co, New York, 1973, p. 36.

[29] Graham, K., An American Girl and her Violin, op. cit, p. 282.

[30] Grieved Over Broken Fiddle, undated clipping, collected with clippings dated February, 1906, MS1780, Scrapbook 1901–06, MdHS, op. cit.

[31] ‘Miss Jackson was Popular’, The Daily Record, Helena, MT, January 3, 1907, MS1780, Scrapbook 1901–06, MdHS, op. cit.

[32] McLaughlin was 36 and divorced; Jackson was 29. Interestingly, while the groom was recorded as a lawyer, no occupation was given for the bride.

[33] Gamba, ‘Violinists at Home and Abroad’, The Strad, London, July 1907, p. 79.

[34] ‘Violin Virtuoso an Albany Farmer’, Albany Argus, New York, March 12, 1911, MS1780, MdHS, op. cit.

[35] De Sayne, E., ‘Wonderful Music Room owned by Washingtonian’, Washington Post, October 24, McKim Fund: Papers of Leonora Jackson McKim, Library of Congress, op. cit.

[36] Jackson McKim, L., Letter to E.H. Jackson, September 7, 1940, op. cit.

[37] Jackson McKim, L., Petition of Executor for Instructions, McKim Collection, Library of Congress op. cit.

Notes for provenance

[1] Bein, Robert, Letter to Dr William Sloan, Chicago, March 17, 1984.

[2] Bein, Robert, Letter to Dr William Sloan, Chicago, March 11, 1986.