When Wilhelmine (Wilma) Maria Franziska Neruda was born in Brünn (now Brno) in the Czech Republic in 1838, the music world looked quite different from today. Female performers were celebrated as singers, tolerated as pianists, but a solo career as a violinist or cellist was out of the question. On the other hand, audiences loved Wunderkinder (child prodigies), who were welcomed everywhere irrespective of their gender or instrument.

A year after Wilma’s birth, the 11-year-old Teresa Milanollo gave a concert with her six-year-old sister, Maria. The sensation this created prompted many parents to promote their own musical offspring, including Wilma’s father, Josef Neruda. [1] Determined to invest in the musical careers of his children, Josef took leave from his work in 1845. Wilma’s eldest sister, Amalie, was taught the piano, while her brother Viktor should have become a violinist and Wilma a pianist.

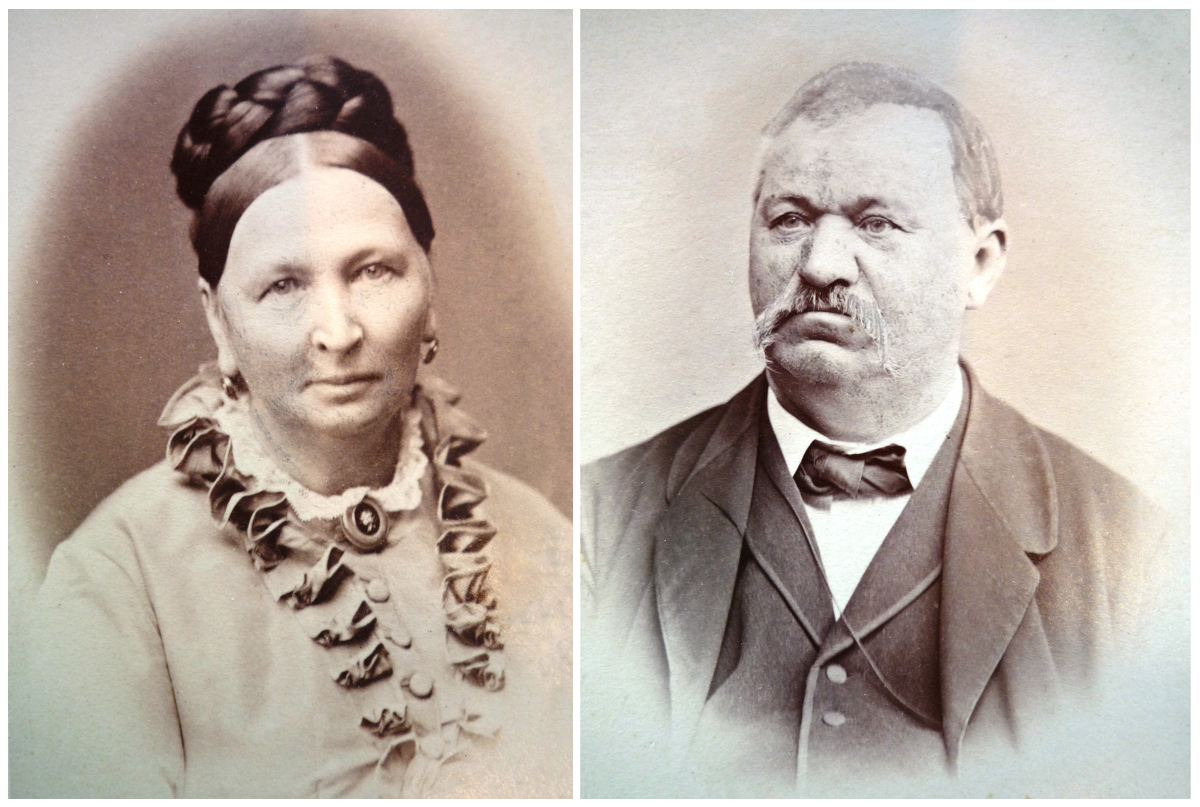

Josef Neruda and his wife, Francisca Merta, Wilma’s parents. Photos: Music and Theatre Library of Sweden, courtesy Jutta Heise

But Wilma was drawn instead to her brother’s violin, which she secretly played. One day her father heard music coming from Viktor’s room and ‘overjoyed at the progress he believed his little son to have made, he rushed upstairs and discovered his mistake!’ [2] He immediately recognized Wilma’s talent. Not only was she allowed to switch to the violin, but she became the focus of her father’s plan. Viktor was given a cello and the family moved to Vienna to seek its fortune. Once there, the eminent Leopold Jansa heard Wilma play and was so impressed that he accepted her as a pupil on condition that he would be her only teacher. [3]

This was the beginning of Wilma Neruda’s extraordinary career. In May 1845 Wilma and Amalie performed publicly for the first time together in Brno to a rapturous response: ‘Wilhelmine Neruda […] is six years old, and does admirable things for her age on the violin,’ wrote one critic. ‘Wilhelmine is said to be gifted with a great, early, extremely rapidly developing talent, and her playing on the instrument, which was previously handled only by men, is characterized by powerful, calm, secure bowing, a full, pithy tone, and the easy, skilful overcoming of technical difficulties.’ [4]

Wilma and Amalie Neruda in around 1847. Photo: National Museum of Denmark, courtesy Jutta Heise

The exploitation of Wunderkinder was hotly debated at the time but, although the Nerudas came in for their share of criticism, some commentators argued that Wilma was a special case: ‘Despite our general position against the Wunderkinder, we must, however, make an exception where the genius of art unfolds its wings and obvious predisposition for the profession of music is at hand, and we must tune into the loud applause which rewarded the talented Wilhelmine Neruda for her achievements,’ wrote one Viennese critic after a concert in 1846. [5]

According to another: ‘The voice of the critics has decidedly spoken out against the breeding of the Wunderkinder for artistic and moral reasons… [but] the small 7-year-old Wilhelmine appears to us to be a talent that develops without tyrannical dressage […]. The girl surprised me and the whole audience, delighted, why shouldn’t I confess it, even moved. Every difficulty on the most challenging instrument, the violin, seems to this child to be a gimmick, and most surprisingly, she knows how to draw such a powerful male tone from her small instrument (a three-quarter violin) that one is often tempted to think that an adult were playing a regular instrument.’ [6]

The Nerudas went on to perform in Germany, Belgium and France before reaching the UK, where their first concert took place at London’s Princess Theatre in April 1849. The audience responded enthusiastically and, instead of two concerts, as originally planned, the siblings made 18 appearances. [7] James William Davidson commented on Wilma’s execution: ‘Her performance of Vieuxtemps’ Arpeggio and Ernst’s Carnaval de Venise are really wonderful, nor does it require any apology on the score of her tender age. After the Milanollos we have no recollection of such remarkable precocity of talent.’ [8]

Lithograph of (left to right) Wilma, Victor and Amalie Neruda around 1850. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The following June, Wilma (now aged 11) was invited to replace Joseph Joachim, who had cancelled an appearance at the Philharmonic Society. Afterwards William Bartholomew wrote to a friend: ‘A little girl – a child in years and person – but a perfect miniature Paganini, played last night to the Philharmonic audience a concerto of De Beriot’s on the violin. Her tone, her intonation, her execution, especially with the bow hand, were all perfect — the latter is beautiful: her graceful and elastic wrist produced some of the most sparkling staccatos by up and down bowing that I have ever heard.’ [9] Joachim himself was so fascinated by Wilma’s style that he confided to his friend Charles Hallé: ‘I recommend to your attention this young lady. Mark my word, when people have heard her, they will not think so much of me.’ [10]

Not everyone joined in the appreciation. Henry Chorley wrote: ‘Wilhelmine Neruda […] has been capitally trained – and may, in time, emulate those more distinguished girl-violinists, the sisters Milanollo; but childish curiosity and indulgent applause […] are not the emotions to excite which the Philharmonic Concerts were founded.’ [11] Years later, the Musical Times dryly commented: ‘It may be doubted whether Mr. Chorley ever looked upon any lady violinists with favour.’ [12]

‘When I first came to London I was surprised to find that it was thought almost improper, certainly unladylike, for a woman to play the violin’ – Wilma Neruda

Wilma herself later reflected on the evolving attitudes to women violinists: ‘When I first came to London […] I was surprised to find that it was thought almost improper, certainly unladylike, for a woman to play on the violin. In Germany the thing was quite common and excited no comment. I could not understand – it seemed so absurd – why people thought so differently here. […] But of course everything is different now, and I dare say more ladies now play the violin in England than in Germany.’ [13]

In late 1849 Josef Neruda decided to bring his children to Russia. Another daughter, Marie, had meanwhile joined her siblings as second violinist. Their Russian tour was a triumph, but life on the road took its toll: Viktor Neruda died aged 15 in 1852, probably as a result of the constant stress of performing and traveling. The Nerudas returned to Brno, but the children weren’t given much time to mourn his death. After a concert in his honor, his place as cellist was taken by his brother Franz and soon enough the young musicians were on the road again in Poland, Germany and, in the 1860s, Sweden and Denmark.

The Neruda Trio, (left to right) Wilma, Franz and Marie, around 1862. Photo: Music and Theatre Library of Sweden, courtesy Jutta Heise

Here and there Wilma’s siblings received appreciation, although they were clearly overshadowed by her. Hans von Bülow wrote that cellist Franz: ‘…takes the same “comprimaria” (as it is called in Italian) position to Master Piatti as his illustrious sister [Wilma] to Master Joachim.’ [14] Another wrote of Amalie, the pianist: ‘She would certainly have all the success she deserves, if she did not make herself heard next to her sister, whose superior talent wipes her out.’ [15]

The income from the Scandinavian tour was so enormous that the Neruda children were able to buy a house for their parents in Brno. [16] After this Wilma began a new life in Stockholm, where she had met Ludvig Norman, composer and conductor at the Royal Music Academy. [17] The two married on January 27, 1864, but Wilma did not give up her artistic career. On the contrary, she performed with her husband and founded ‘a concert company in Stockholm to promote chamber music works in Sweden.’ [18] Not even two pregnancies (her sons Ludvig and Waldemar were born in 1864 and 1866 respectively) kept her away from the stage for more than a few months.

But soon enough the Normans grew apart. It is evident that, despite her children and her position as professor of violin at the Royal Academy of Stockholm, [19] Wilma wished to leave Sweden. By 1869 they had separated and Wilma returned to touring Europe. She was now at the pinnacle of her career: ‘One would feel tempted to call her a female Joachim,’ a Berlin journalist wrote enthusiastically. [20]

Wilma Neruda in around 1870, after her separation from Ludvig Norman. Photo: Music and Theatre Library of Sweden, courtesy Jutta Heise

In the UK, where she took up residence, Wilma was in great demand. She played at the London Philharmonic Society, with the English Joachim Quartet, and at the Popular Concerts at St James’s Hall, where she was the first woman to lead chamber music. She was also often to be heard with Charles Hallé’s Orchestra in Manchester and gave joint concerts with players such as Joachim, Piatti, Ries, Clara Schumann and Vieuxtemps.

Hans von Bülow named her ‘Geigenfee’ (violin fairy) and wrote: ‘the miracle girl Wilma Neruda has become a miracle woman and in England she rules as the violin king of Apollo’s grace and with the consent of all music connoisseurs […]. The spirit, the soul, the life, the warmth, the nobility, the style, from the innermost resonance into the work of art […] therein lies the secret power of this sorceress over the hearts of the audience.’ [21]

Wilma was even mentioned by Sherlock Holmes: ‘Her attack and her bowing are splendid. What’s that little thing of Chopin’s she plays so magnificently: Tra-la-la-lira-lira-lay,’ the famous detective chattered away in his first adventure. [22]

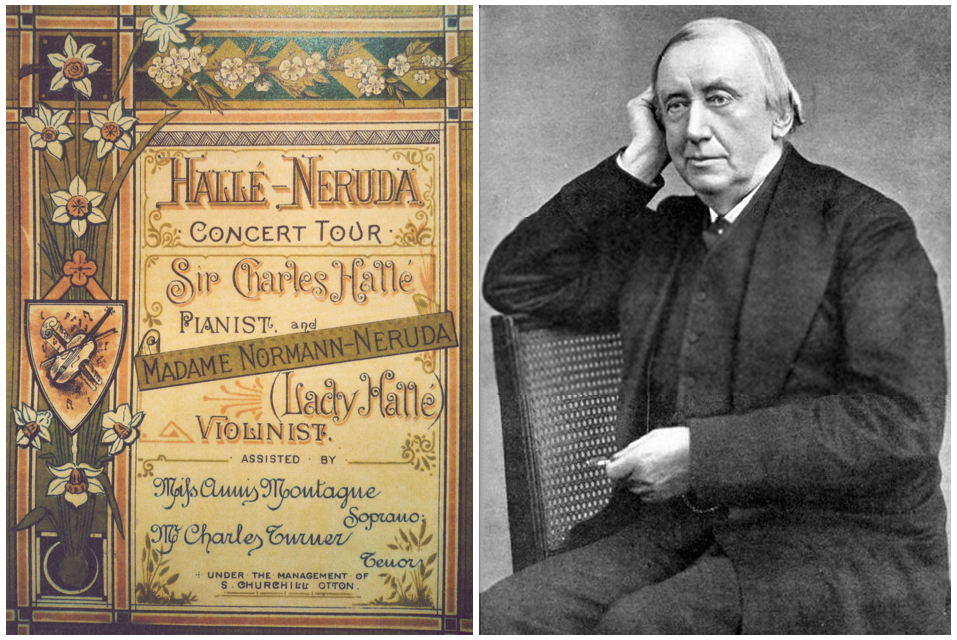

Left: a program from one of the Hallés’ concert tours; photo: Music and Theatre Library of Sweden, courtesy Jutta Heise. Right: Charles Hallé; photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ludvig Norman died in March 1885. [23] Three years later Wilma became engaged to Charles Hallé, who had been a close friend for decades. Hallé was knighted by Queen Victoria in June 1888 and, after their marriage the following month, Wilma became Lady Hallé. A few weeks later Hallé wrote: ‘The unbounded admiration which I have felt for so many years for this lady, who is my wife now, made the idea that perhaps some time or other our paths might run in different directions perfectly unbearable to me; all my artistic aspirations have centered so long in her that my life would have been a blank without her.’ [24]

Left: Wilma Neruda engraving; photo: Wolfgang Moroder. Right: portrait of Wilma Neruda by George Frederick Watts; photo: Wikimedia Commons

Despite their considerable age difference (Charles was 69 and Wilma 50), the union was successful both on the stage and in private. They continued to perform together and went on tour, although Wilma also concerted alone. She was in Denmark when Hallé suddenly died on October 25, 1895. About a month later, the Prince of Wales started a public subscription to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Wilma’s first appearance in public and the 25th anniversary of her UK debut. She was presented with a castle at Asolo, near Venice, where she resided for some years with her son Ludvig. [25] After Ludvig’s death in 1898 she moved to Berlin, to teach at the conservatory.

England did not forget Wilma, and her good friend Queen Alexandra named her ‘Violinist to the Queen’ in 1901. Aged 73, Wilma was still enchanting her audience in concerts with Hugo Becker and Pablo Casals in March 1911. A month later, on April 15, 1911, she died in Berlin. She will be remembered as ‘the first woman violinist to have been considered good enough to rank with the greatest male performers.’ [26]

Thanks to Jutta Heise, Katalin Zsigmondy Zirner, August Zirner, Roberto Regazzi, the Music and Theatre Library of Sweden, and the National Museum of Denmark.

Alessandra Barabaschi is an Italian art historian and has authored several books including the four-volume ‘Antonius Stradivarius’.

The ‘Ernst, Lady Hallé’ Stradivari

By her own account Wilma had always been ‘very anxious to have a “Strad”.’ [27] On the occasion of a concert in Edinburgh, she contacted the violin dealer David Laurie and asked to be brought some instruments to try. Laurie showed her, among others, ‘a most undeservedly maligned instrument,’ [28] the 1709 ‘Ernst’ Stradivari, which had been the concert instrument of Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst until his death in 1865. Wilma was initially sceptical about trying this violin, whose tone had been criticized, but she fell in love with it. Three noble patrons, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and the Earls of Hardwicke and Dudley presented her with the violin in 1875. [29]

Although Wilma owned several instruments, this became ‘her sole concert instrument.’ [30] Years later she recalled: ‘I love my Stradivarius, and for me there exists not a violin to surpass it in the exquisite delicacy of its intonation.’ [31] The Hills commented: ‘We recall a violin of special tonal merit made in 1709 – Lady Hallé’s, formerly Ernst’s. And who that has heard Lady Hallé play will not bear this statement out? The ripe, woody, and yet sparkling quality, its perfect responsiveness and equality on all the strings, and the ever-swelling sonority, all contribute to delight the cultivated listener.’ [32]

The violin, now known as the ‘Ernst, Lady Hallé’, was played for over 30 years by the Hungarian soloist Dénes Zsigmondy, who died in 2014.

Notes

[1] Josef Neruda had received an extensive musical education in the Benedictine monastery of Rajhrad and was organist at Brno Cathedral: Heise, Jutta, ‘Die Geigenvirtuosin Wilma Neruda (1838-1911)’ in: Studien und Materialien zur Musikwissenschaft, Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim, 2013, p. 49.

[2] Baroness von Zedlitz, ‘A Chat With Lady Hallé’, in: Cassel’s Family Magazine, 1894, p. 780.

[3] Heise, J., ‘Die Geigenvirtuosin Wilma Neruda (1838-1911)’, op. cit., p. 29.

[4] ‘Musikalisches’, in: Stiria, No. 62, Graz, May 24, 1845, p. 247.

[5] ‘Wiener Konzerte’, in: Wiener Zuschauer, No. 207, Vienna, December 30, 1846, p. 1655.

[6] ‘Sonntag den 27. d. M. Konzert der Wilhelmine Neruda im Vereinssaale’, in: Wiener Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung, No. 157, Vienna, December 31, 1846, p. 641

[7] ‘Lady Hallé’s First Appearance in England’, in: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, vol. 41, no. 692, October 1, 1900, p. 653.

[8] Davidson, James William, in: The Times, London, May 7, 1849.

[9] Bartholomew, William, Letter to Joseph Moore, first appeared in: ‘Lady Hallé’s First Appearance in England’, op. cit, p. 654.

[10] Engel, Louis, From Handel to Hallé – Biographical Sketches, Swan Sonnenschein & Co., London, 1890, p. 240.

[11] Chorley, Henry Fothergill, in: The Athenæum, London, June 16, 1849.

[12] ‘Lady Hallé’s First Appearance in England’, op. cit, p. 654.

[13] Dolman, Frederick, ‘Lady Hallé at Home’, in: The Woman’s World, London, 1890, p. 171.

[14] Bülow, Hans von, ‘Skandinavische Conzertreiseskizzen III’, in: Allgemeine Deutsche Musik-Zeitung, no. 19, Berlin, May 12, 1882, p. 160.

[15] B. Dameke, ‘Chronique musicale de Saint-Pétersbourg’, in: Revue et Gazette Musicale de Paris, no. 23, Paris, June 8, 1851, p.187.

[16] Heise, J., ‘Die Geigenvirtuosin Wilma Neruda (1838-1911)’, op. cit., p. 76.

[17] Ludvig Norman is known to have suffered from depression and probably Tourettes syndrome. Nevertheless, von Bülow spoke highly of him: ‘Many years of physical suffering have brought the artistic activity of the excellent composer and conductor to a standstill, albeit not completely, but they often inhibit his evolvement to the advantage of the capital’s musical life.’

[18] Heise, J., ‘Die Geigenvirtuosin Wilma Neruda (1838-1911)’, op. cit., p. 29.

[19] ‘Wilhelmine Maria Franziska Neruda Lady Hallé’, in: The Strad, London, March 1893, p. 210

[20] ‘Correspondenzen’, in: Neue Berliner Musikzeitung, no. 7, Berlin, February 17, 1869, S. 52.

[21] Bülow, Hans von, ‘Die Geigenfee’, in: Signale für die musikalische Welt, no. 16, Leipzig, February 1880, p. 243.

[22] Conan Doyle, Arthur, A Study in Scarlet, 1887, reprint 1987, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, p. 44. Holmes also mentions Wilma Neruda on p. 40.

[23] It has been speculated that Wilma Neruda and Ludvig Norman divorced, but there is no official document to substantiate this.

[24] Charles Hallé letter to E. J. Broadfield, in: Beale, Robert, Charles Hallé: A Musical Life, Ashgate, Aldershot, 2007, p. 184.

[25] Anthony G. Morris was able to retrace the relationship of Lady Hallé to Asolo. Morris’s engagement with Lady Hallé grew out of a very personal geographical and musical coincidence: his business studio near Garmisch-Partenkirchen had once belonged to the Hon. Miss Mary Portman, distinguished violinist and original owner of the “Mary Portman” Guarneri. That discovery sparked a deeper curiosity about Portman herself and, in turn, about her close friend Lady Hallé. Tracing references to a palazzo in Asolo, allegedly given to Lady Hallé by the then Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), Morris travelled to Asolo only to find that local knowledge of her presence there had largely vanished. On the basis of contemporary descriptions and comparative evidence, he identified the present Municipio as the former palazzo in question and reintroduced this connection to the Asolan community through an article published in Jan. 2006 in the Treviso Tribune. Since then, Lady Hallé’s Asolo links and wider celebrity network have been integrated into the Asolo Wikipedia entry and the town’s online presentation, and several researchers have begun to pursue the town’s musical history more actively. More recently, Morris has extended his research to Lady Hallé’s final years in Berlin: he has located the exact position of her long-neglected grave, assumed formal “Patenschaft” (grave sponsorship) for the site, and is currently leading the application to the Berlin Senate for its recognition as an Ehrengrab (Honorary Grave), supported by a broad alliance of international artistic and educational institutions.

[26] Rigby, Charles, Sir Charles Hallé – A portrait for today, The Dolphin Press, Manchester, 1952, p. 126.

[27] Dolman, F., ‘Lady Hallé at Home’, op. cit., p. 173. When Wilma Neruda was still a child, the following news was released: ‘A noble lady from the chamber of Her Majesty the reigning Empress presented the little violinist Neruda with an excellent Stradivarius violin’, Der Humorist, No. 14, Vienna, January 16, 1847, p. 56. However, Wilma Neruda declared she had never owned a Stradivari violin before 1875; therefore this news has to be considered incorrect.

[28] Laurie, David, The Reminiscences of a Fiddle Dealer, T. Werner Laurie, London, n.d., p. 141.

[29] ‘Dur und Moll’, in: Signale für die musikalische Welt, no. 9, Leipzig, February 1875, p. 139.

[30] Eshbach, Robert W., ‘Wilhelmine Maria Franziska Norman-Neruda, Lady Hallé’, in: Die Tonkunst, April 2011, p. 195

[31] Baroness von Zedlitz, ‘A Chat With Lady Hallé’, op. cit, p. 781.

[32] Hill, W.H.; Hill, A.F.; Hill, A.E., Antonio Stradivari. His Life and Work (1644–1737), W.E. Hill & Sons, London, 1902, reprint 1963, Dover, New York, p. 153.