This is a fascinating story and it speaks volumes about how much the violin industry has changed in the past thirty years. Today, we have publicly accessible archives, information is shared generously among colleagues and the standards of due diligence in certifying and selling instruments are much, much higher. Tarisio and the Cozio archive have been at the vanguard of this evolution and, in fact, Tarisio plays a central role in the story of the ‘Mendelssohn’ Stradivari. But here’s the real shocker: I know this violin. I have held it in my hands many times; I photographed it; it even lived in the Tarisio vault for several months in the autumn of 2000. But that was long before I knew – to be clear, this was long before anyone knew – that this was the stolen ‘Mendelssohn’ Stradivari.

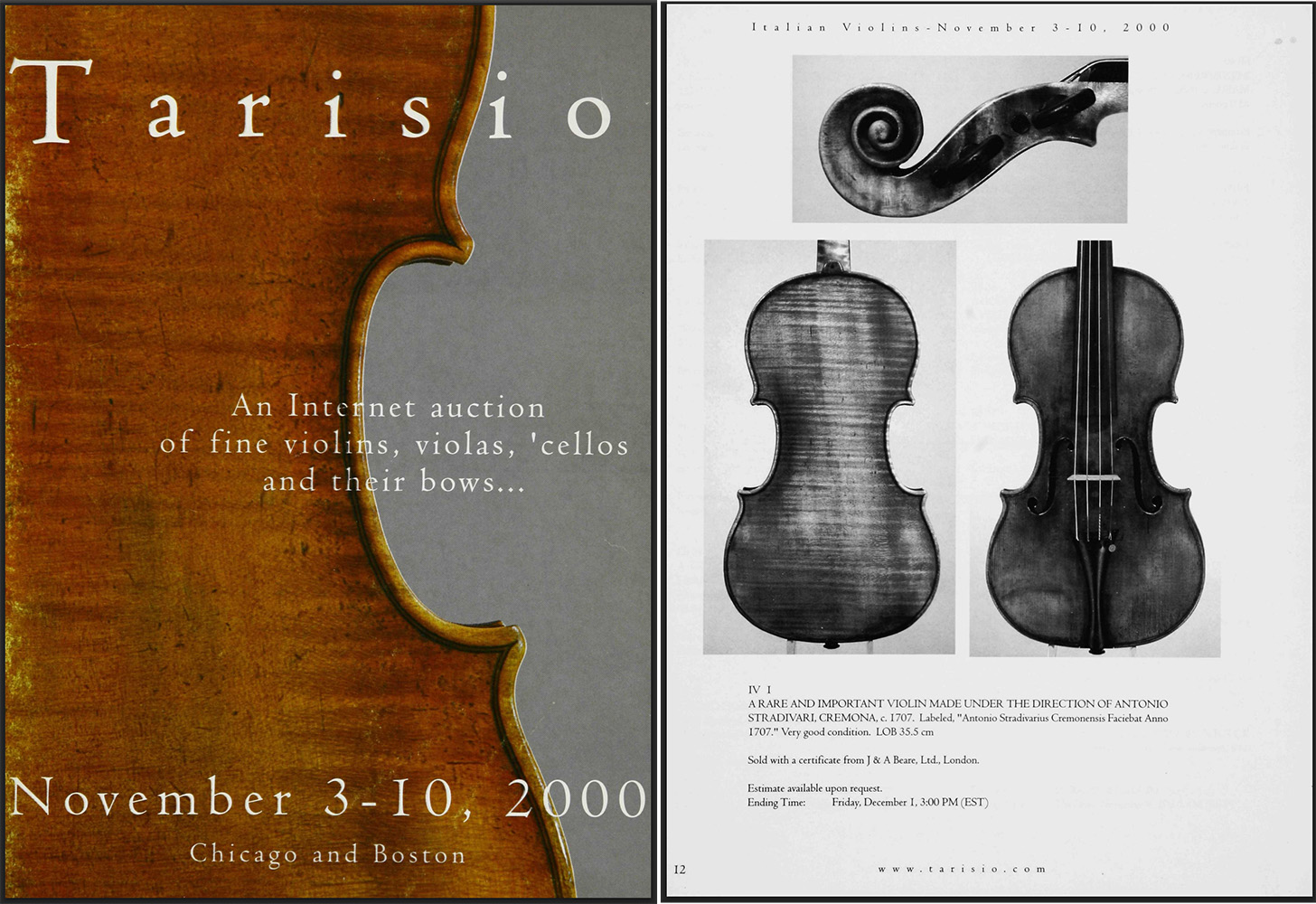

The 1709 ‘Mendelssohn’ Stradivari (left) as illustrated in the September 1958 issue of The Strad magazine, and the c. 1707 Stradivari.

In the 1920s, the 1709 ‘Mendelssohn’ Stradivari was owned by violinist Lilli von Mendelssohn-Bohnke. Lilli came from a family of powerful German bankers and respected musicians. Her father was a violinist, her uncle was a cellist and her second cousin twice removed, was Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. The family-owned private bank, Mendelssohn & Co, was started by Lilli’s great-great-grandfather in 1795 and by the early 20th century, it had become one of the most powerful private banks in Germany. When Lilli died tragically in a car crash in 1928, her Stradivari was deposited in the vault at the Mendelssohn Bank for safe keeping.

The Mendelssohn family was Jewish and the Nazi race laws of the mid 1930s made it illegal for Jews to own property. In December 1938, the Mendelssohn-Bohnke home was sold under duress and the Mendelssohn Bank was forced into liquidation and taken over by the German Ministry of Finance.

After World War II, the family was informed that the Stradivari had been moved to the headquarters of the Deutsche Bank and had then disappeared. To this day, it is not clear if the violin was stolen by the Nazi regime or if it was looted by the Soviets who occupied that sector of Berlin after the war ended. In either scenario, the laws of most countries agree that this is a stolen violin whose rightful owners are the descendants of the Mendelssohn-Bohnke family.

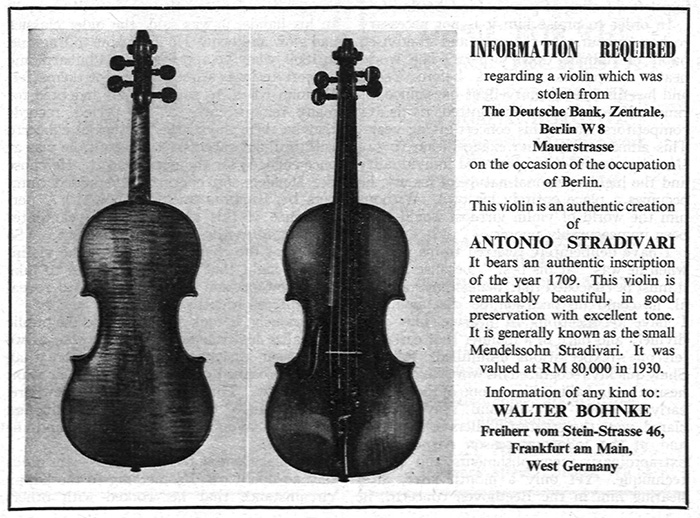

Lilli’s youngest son, Walther, placed stolen property reports in several publications, seeking the return of the Stradivari. The most relevant of these, for our purposes, is an advertisement in The Strad magazine in September 1958. Apart from this and a mention in Herbert Goodkind’s 1972 Violin Iconography of Antonio Stradivari 1644-1737 (without photographs), there was no mention of the 1709 ‘Mendelssohn’ Stradivari until 2009 when my colleague, the relentlessly determined researcher of wartime and stolen violin claims, Carla Shapreau, wrote about it in The Strad magazine.

An advertisement taken out by Walther Bohnke in The Strad magazine in September 1958.

In 2015 Shapreau published another article, this time on Tarisio and with it, Tarisio launched its stolen instrument registry, a list of historical and current missing instruments. The list includes important stolen Stradivari including the 1727 ‘Davidoff-Morini’, the 1735 ‘Lamoureux, Zimbalist’ and the 1716 ‘Colossus’, and it also includes instruments by less famous makers like Postiglione, Landolfi, Catenari and Lorenzini. The ‘Mendelssohn’ featured prominently on the registry.

![]()

And here’s where the story splits. The ‘Mendelssohn’ had actually resurfaced in Paris in around 1995, although it was not associated with the Mendelssohn name and it was dated to c. 1707. There is no indication that the dealer who was handling the violin had any knowledge of the Mendelssohn connection but there’s much that remains unclear about the whereabouts of this violin after the war and how it reappeared.

In 1995, the violin was brought to Charles Beare in London who certified it and dated it to c. 1705 – 1710. Five years later, it was consigned to Tarisio to be sold. The violin didn’t sell at auction in November 2000, but that was more a statement of the times and circumstances than about the violin itself. The dot-com bubble had just burst and there was plenty of general uncertainty in the markets. As fate would have it, the fact that it didn’t sell was the best outcome; laws vary, but generally speaking, good title doesn’t pass with a stolen violin.

Our November 2000 sale featured this Stradivari on the cover of the catalog.

After the violin failed to sell at auction, we returned it to the consignor and that was the last I heard of it until last summer. However, we now know that the violin was sold to a well known Japanese musician in or around 2005. In documents that accompanied the sale the violin was called the ‘Stella’ and it was accompanied by a provenance saying it had been “in the possession of a noble family which has been living in Holland since the times of the French Revolution.” The name ‘Stella’ and the spurious Dutch provenance were not known to Tarisio in 2000.

So how did we discover that the ‘Stella’ was in fact the ‘Mendelssohn’? On June 20, 2024, Shapreau recognized that these two instruments were, in fact, the same. The photographs published in 1958 are of extremely poor quality but the Mendelssohn family had shared the original black and white images that were used to make the 1958 advertisement with Shapreau. In those images, we can confirm that the ‘Stella’ and the ‘Mendelssohn’ are one and the same. Shapreau has written a comprehensive summary of the ‘Mendelssohn’ Stradivari’s disappearance and reappearance on her research website here.

![]()

The landscape of fine instrument dealing has changed significantly over the past thirty years. Today, the fine instrument market is far more transparent, informed and protected thanks to advances in technology, readily available images and global communication.

It has always been the responsibility of dealers and auction houses to use all available resources and reasonable efforts to perform due diligence and ensure that property changes hands with clear title. However, “available resources” and “reasonable efforts” are relative terms. Today’s expectations – and resources – are much greater than they were thirty years ago and consequently, the standards for provenance research, title clearance, condition reporting and authenticity have risen sharply.

The Cozio Archive is responsible for many of these changes. Started by a data scientist in 2003, the Archive was purchased by Tarisio in 2012 and is a constantly evolving resource. We compile data from all auction houses, dealer websites, new publications and many private archives. Much of the archive data is not available publicly but it is available for research and consultation. Cozio also maintains a Stolen Instrument Register and a companion Register of Recovered Instruments. Transparency and readily available information is crucial to making safe transactions and maintaining buyer confidence.

Data and documents from the Cozio archive were crucially important in reconstructing the diverging provenance of the ‘Stella’ and the ‘Mendelssohn’. The two instruments’ records have been merged and the instrument is now called, the ‘Mendelssohn’.

So this all begs the question, What if a stolen Stradivari surfaced at an auction house or violin shop today? Given the data we have available and the interconnectedness of this community, it’s virtually impossible that a stolen violin could resurface unnoticed. And this should give great comfort to buyers and sellers alike.

![]()