Though not as acquisitive as Kreisler, Henryk Szeryng seemed to attract violins like a magnet. In his book Violin Virtuosos, Henry Roth lists ‘two Stradivari, one Andrea Guarneri, a fine Gofriller, two Vuillaumes (one of which is a copy of the “Messiah” Strad) and, of course, the magnificent 1743 “Le Duc” Guarnerius del Gesù. … During his final period, in addition to the “Le Duc”, he played on two French violins, one by Pierre Hel made in 1922 and the other by Jean Bauer, a contemporary maker.’ [1] And as we shall see, there were a few others.

Szeryng was the most cosmopolitan violinist of his generation. Born Henryk Serek into a well-to-do, cultured family on September 22, 1918 in Chopin’s birthplace Zelazowa Wola, near Warsaw, he knew Paderewski and Huberman as friends of his parents. When he was five his mother started teaching him piano and harmony, but at seven he changed to his elder brother Jerzy’s instrument, the violin, taking lessons with Leopold Auer’s former assistant Moriz Frenkel. It was Huberman who suggested in 1927 that he should be sent to study with Willy Hess, Carl Flesch or Jacques Thibaud and provided a letter of introduction to Hess. Henryk had a year with Hess in Berlin, but found him old-fashioned and changed to Flesch.

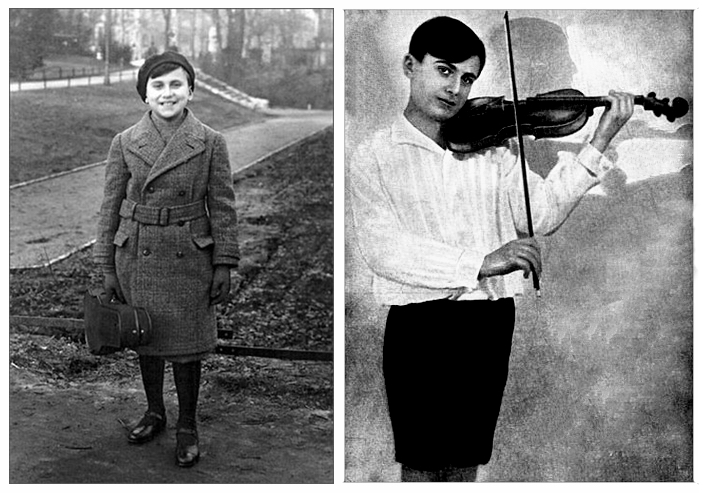

The young Henryk Szeryng in 1929 (left) and 1935

By 1933 he was touring, but his parents wisely decided he should study further and in Paris he worked with Gabriel Bouillon and Mlle Berthelier for violin and Nadia Boulanger for composition, also coming under the influence of Thibaud. Eager for knowledge, he was soon speaking six languages (later he commanded 11). ‘Violinists should obtain a good general education, particularly in the humanities, in history and languages,’ he said years later. ‘The study of music should include the sciences of acoustics and mathematics. Their musical education should include harmony, counterpoint, piano, orchestra, opera, etc. A violinist can learn a good deal from singers and from pianists.’ [2]

During the Second World War Szeryng became invaluable to the Polish government in exile as General Sikorski’s personal liaison officer. In 1942 he accompanied the general to Mexico to seek asylum for 4,000 Polish refugees. The Mexicans’ generous response led to Szeryng’s taking their citizenship after the war and teaching at the university in Mexico City.

Szeryng with his compatriot Artur Rubinstein in Hollywood, 1960. Photo: Tully Potter Collection

In 1954 Artur Rubinstein suggested he should resume his career. Szeryng was ready and, helped by publicity generated by duo concerts and recordings with his fellow Pole, began a brilliant rise to fame. He retained his links with Mexico, championing composers such as Chávez and Ponce – when I first heard him more than 50 years ago, he dazzled with his renderings of Central and South American pieces – and in 1956 was made an official Mexican cultural ambassador, travelling on a diplomatic passport. In 1970 he became cultural adviser to Mexico’s UNESCO delegation in Paris. All this time he carried on a front-rank concert and recording career. And he found time to be a fair pianist, a skill that gave him an exceptional understanding of his duo partners; he would play jazz piano for friends after hours, although he said: ‘I was always reticent to use the violin for that kind of music.’

The first violin we can be sure Szeryng owned was the c. 1760 Tomaso Eberle he had from 1938 to 1946: it came in for some strenuous use during the war. ‘I was not quite satisfied with only doing my duty,’ he told Simon Collins in 1978, ‘and fortunately I was permitted to carry my violin with me – at that time it was not a Strad, a Guarnerius, Amati or a Ruggieri, nor was it a Ceruti, Carcassi or a Guadagnini, but it was a nice violin and I liked to play it. Nobody really knew what it was – it was supposed to be an Eberle: Tyrolean with a Venetian influence. Anyway, it sounded fine to me, and I played very many concerts – I would say over 300 – for casualties, for the wounded and sick members of the Allied forces, for their families and even for prisoners of war.’ [3] This historically important violin is now in Argentina.

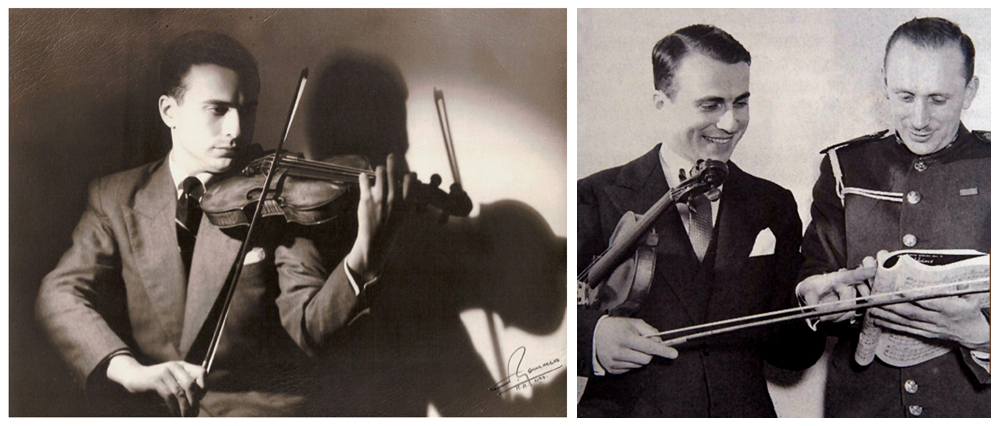

Left: Henryk Szeryng playing the Eberle in 1944; right: with Sergent Major E. Kirkwood in Canada, 1943

In his heyday Szeryng habitually had two violins in a double case, a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ and a Stradivari, and alternated them. ‘Fortunately, the tone of the Stradivarius is dark enough and the Guarneri light enough that the transition is not felt to be painful,’ he said. [4] From about 1957 he had the ‘Leduc’ Guarneri on loan from the Phipps family foundation and eventually bought it in 1970. This violin, thought to be the last that ‘del Gesù’ made, has a badly written label dating it to 1745, the year after the luthier died, so various attempts have been made to read the date as 1743, or to fudge it as ‘c.1744’. Some have speculated that the instrument might have been finished by Guarneri’s wife Katarina after his death. Whatever the confusion over its completion, the ‘Leduc’ was described by Jacques Francais as one of the best concert violins in the world.

Szeryng’s Stradivari was the 1734 ‘Hercules’, once owned by Eugène Ysaÿe but stolen from the Green Room at the Imperial Theatre in St Petersburg in 1908, while Ysaÿe was on stage playing his Guarneri. In 1925, having surfaced in a Parisian dealer’s shop, the Strad was acquired for the Alsatian violinist Carl Münch, then concertmaster at the Leipzig Gewandhaus and later famous as the conductor Charles Munch, by his wife. Szeryng originally borrowed the ‘Hercules’ from Munch for some performances of the Schumann Concerto and bought it from him in January 1962 for $40,000.

Gary Graffman, who appeared several times with Szeryng at the Library of Congress in Washington, recalled: ‘He travelled with two violins, a Strad and a “del Gesù”, and my wife had to sit backstage cradling whichever one he wasn’t using.’ [5] Szeryng was obviously not going to make the same mistake as Ysaÿe! However, he was not averse to letting a valued colleague play his instruments, as his fellow Flesch pupil Peter Rybar, longtime concertmaster in Winterthur, averred: ‘When Henryk Szeryng came for his first rehearsal in Winterthur, he was expecting to play the Brahms and was told the orchestra was expecting to play the Tchaikovsky! One of the board of directors, who had a nice Steinway, always invited the soloist for dinner, usually with me as well. Szeryng told me he knew my record of the Schumann. “I love that concerto,” he said. For coffee we had to go into the salon but at that moment Henryk took me by the arm towards the Steinway, said, “There’s my case, open it and take out one of my violins”, then sat down and we ran through the whole Schumann Concerto, Szeryng playing by heart.’ [6] (The friendship with Rybar is immortalised in the better of Szeryng’s two recordings of Bach’s Double Concerto.) In 1972 Szeryng donated the Strad to Mayor Teddy Kollek of Jerusalem, to mark the forthcoming silver jubilee of the state of Israel. Now known as the ‘Kinor David’ (Lyre of David), it is used by the Israel Philharmonic concertmasters.

‘Szeryng travelled with two violins, a Strad and a “del Gesù”, and my wife had to sit backstage cradling whichever one he wasn’t using’ – Gary Graffman

This gift triggered an avalanche of largesse from Szeryng. Small, voluble and ebullient, he could be bumptious, vain and irritating, and the despair of concert promoters and record company executives, but at heart he was a generous man. ‘I had a very remarkable Andrea Guarneri, the “Santa Teresa”, which was made in 1683,’ he told Collins. ‘It has a quite incredible tonal beauty; although it is probably not quite as powerful as the Stradivarius which I gave to Jerusalem, it is beautiful, tender and rich in colour. Strangely enough, since I gave this violin to the Republic of Mexico for use by the first leaders of the National Symphony Orchestra of Mexico, I think that it has gained. The quality is there, undoubtedly, but the volume has improved somehow.’ [7]

To his pupil and protégé Shlomo Mintz, Szeryng gave a fine old French fiddle by Jean-François Aldric, of which he said that it was ‘quite extraordinary’ and Mintz had often been asked if it was a Strad. [8] To his student and teaching assistant in Mexico, Ecuadorean-born Enrique Espín Yepez, a professor at the National Conservatory, he gave his 1801 violin by the Cremona maker Giovanni Battista Ceruti. His Vuillaume copy of the ‘Messiah’ Strad, bought from W.E. Hill in the 1970s, was donated to the Principality of Monaco. In addition he began giving away some two-thirds of his income. By the time of his death – which came suddenly in Kassel on March 3, 1988 – Szeryng was left with his Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, his Hel and his Bauer.

Henryk Szeryng gave away most of his violins towards the end of his career, including the ‘Hercules’ Stradivari

Szeryng accumulated a superb collection of French bows, including an Eugène Nicolas Sartory; a gold and ivory François Nicolas Voirin, exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1882; a gold- and tortoiseshell-mounted Dominique Peccatte from the late 1840s, once owned by Ysaÿe and now used by Vadim Gluzman; a gold and tortoiseshell Etienne Pajeot, once owned by Camillo Sivori; and a gold and tortoiseshell Lamy. He also had a modern bow from Berg Bows and another made for him in Paris by Benoît Rolland. But he told the violinist Michael Pearson that he used German bows almost exclusively. Incidentally, like George Enescu, he usually played with the bow hair quite slack.

According to Szeryng’s widow Waltraud: ‘[his] bow collection consisted essentially of Dominique Peccatte, Tourte, J.B. Vuillaume and F.N. Voirin bows, all fine examples of their respective mastery. His “everyday tools” were definitely Peccattes: his favorite one, especially in the last years, was the “ex-Eugène Ysaÿe” Dominique Peccatte. He used this bow exclusively during the last four years of his life. A number of his bows – and very often they were Peccattes – he gave away, the same as he did with his violins. I witnessed one of these moments when, after a rehearsal, all of a sudden he took out a bow from his violin case and handed it over to an incredulous violinist, leader of the chamber music ensemble with which we were on tour and with whom performing was each time a profound pleasure for him. Another Peccatte went to one of the section leaders of a worldwide-known major orchestra. Henryk presented UNESCO with another of his Peccatte bows, which was then sold in an auction and bought by Etienne Vatelot. The proceeds went to the Fédération Internationale d’Entraide aux Musiciens. All his bows are now in different hands throughout the world.’

Of his many gifts to others, Szeryng said: ‘Although many people consider that these are terribly altruistic deeds, I believe that there is some selfishness as well in doing this. I feel that there is some kind of simultaneous vibration between myself and those who play the violins which, let us say, physically belonged to me before; but possession is not only physical.’ So, like many another great musician we could name, Henryk Szeryng was something of an enigma.

Tully Potter is a journalist and music critic. He is a regular contributor to various international music journals and has written a biography of Adolf Busch.

Notes

[1] Henry Roth, Violin Virtuosos: From Paganini to the 21st Century, California Classics Books, 1997.

[2] Samuel & Sada Applebaum, The Way They Play, Book 3, Paganiniana Publications, Inc, 1975.

[3] Simon Collins, ‘Henryk Szeryng’, The Strad, Vol. 89, 1978.

[4] Quoted in Christoph Schlüren, ‘Dense, Crystal Clear, Saturated with Expression’, essay with Hänssler Classic CD.

[5] Interview with the author, 2004.

[6] Interview with the author, 2001.

[7] Simon Collins, op. cit.

[8] Simon Collins, op. cit.