When viewing a ‘del Gesù’ violin we can simply admire the genius of an extraordinary master. But to appreciate his work fully it must be placed in the historical perspective of what we know about his character and life. Otherwise, his greatness can be obscured or simply overlooked as the undisciplined work of a good maker who did not take his own talents seriously.

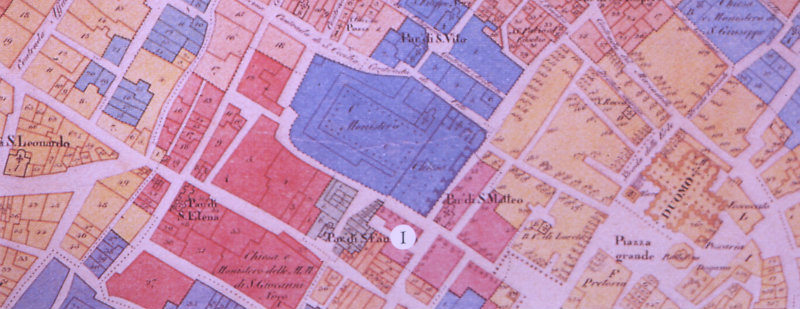

Map of Cremona from c. 1750 showing the location of the Casa Guarneri (I). Photo: Peter Biddulph Ltd

In our previous articles (Part I, Part II and Part III) we examined the life and work of this great violin maker as far as history reveals it, but it would be wrong to ignore the myths and plain inaccuracies still surrounding his name. It is important to show how they originated and how they have colored our views about the life of a maker who was actually a surprisingly normal 18th-century craftsman, yet who exerted a huge influence on the history of the violin.

The main source for the ‘del Gesù’ myth was Francois Fétis. In his book on Stradivari, ‘Antoine Stradivari, luthier célèbre’, published in 1856, he added a few chapters about other Cremonese makers, including the Guarneris. His information mainly came from J.B. Vuillaume, who in turn reported rumors collected from the last of the Bergonzis (Carlo II, although Fétis refers to him as ‘old Bergonzi’). Fétis was writing more than 110 years after the death of ‘del Gesù’ and it is hard to believe that any reliable knowledge of the life of a somewhat obscure and minor maker (as ‘del Gesù’ was considered in the early to mid-19th century) still remained in Cremona.

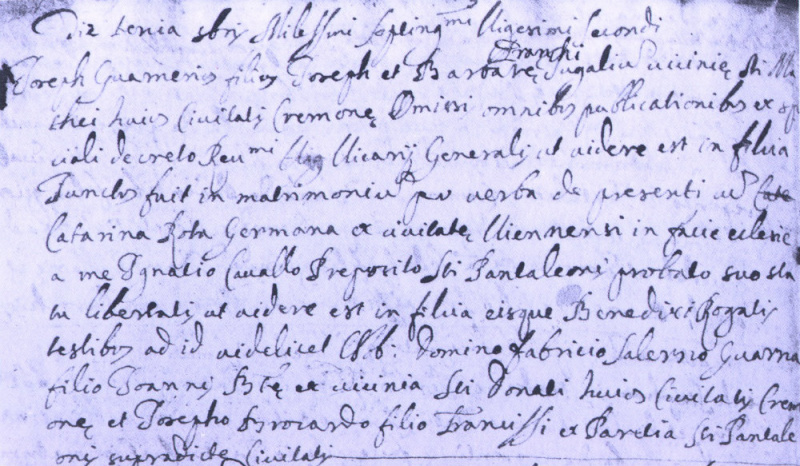

Fétis wrongly stated that ‘del Gesù’ did not come from the Guarneri violin making family, and we can understand why when we consider how unusual it was in Italy (unlike in contemporary England or Germany) to find a family in which a father and his son bore the very same name. He then added some rumors. In his favor, one has proved true: ‘del Gesù’ really did marry a German woman, Catarina Rota (or Roda). Carlo Bergonzi specified that she was never happy with her husband and that she helped him in the workshop. We hope the first part was false; we may never know for certain if the second was true, but it might be.

The record of Giuseppe Guarneri and Catarina Rota’s marriage in 1722. Photo: Peter Biddulph Ltd

The main core of the legend, however, was that ‘del Gesù’ spent the last years of his life in a prison, where he worked thanks to the help of a woman (said to be the jailer’s daughter in some versions) who supplied him with the tools and materials to make a living as a violin maker and even worked with him. This rumor was old: Count Cozio of Salabue heard it in 1816, but wisely made a note to check if there was any chance it was true. Seen in a historical perspective, there is no hope it was: if you had the unlucky fate to end in a prison in Cremona in the early 1700s, you were not moving to a nice building with space, tables, light and provisions, but to a horrible cellar waiting to be carried to a rowing seat on a Venetian vessel or to the gallows.

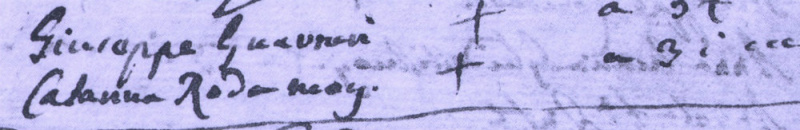

This record from 1729 lists Giuseppe Guarneri and Catarina Rota as living in the Quarter of Santa Maria Nova. Photo: Peter Biddulph Ltd

But if this is not convincing enough, there are documents showing that in every year of his life during the period in which he worked as a violin maker, ‘del Gesù’ lived with his wife in a building in the center of Cremona and took the holy communion in church at Easter time. In the middle of this period, in 1733, a priest dictated his last will to a notary, and among the list of witnesses called to the ceremony we find ‘del Gesù’: clearly he was considered a man of trust.

The identification of Giuseppe ‘del Gesù’ as the youngest son of Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ is beyond any possible doubt, as the Hills showed in their seminal book on the Guarneris. He was baptised with the name ‘Bartolomeo Giuseppe’, but from the census returns we learn that from his birth the child was called simply Giuseppe, the same name as his father (who in turn was baptised ‘Giuseppe Giovanni Battista’, but surely never used any name but the first). The younger Giuseppe lived with his family until he married in 1722.

At that point he left the family home and stopped working with his father. In a notarial act written in 1738 he stated that by then he had been living and working independently for 17 years, that is, from the time of his marriage. We do not know what his profession was in the early years of his independent life, and there are no surviving instruments to suggest he worked as a violin maker on his own. In about 1726 he started to build instruments again, but remained independent from his father. This was a surprising choice: before him in Cremona only Vincenzo Rugeri had worked on his own in a workshop other than that of the family, which by tradition and law was run and owned by the patriarch. Setting up an independent business was an unusual and bold action.

Both Fétis and Cozio refer to violins made by ‘del Gesù’ in the years 1726–29, all bearing a label with an enlightening text: ‘Joseph Guarnerius Andreae nepos’, which identified him as the grandson of Andrea. With this label the young maker found a brilliant way to let his customers know that he was from the famed Guarneri family, but he was not the ‘old’ Giuseppe. At the same time, he cleverly avoided mentioning his father, who was sadly in his last days as a master violin maker: in 1728 he rented the old family workshop to a shoemaker, final proof of the decline of his working abilities. It took only a few months for his son Giuseppe to print a new label in which there was no longer any reference to the family: by this stage, he was the only Guarneri luthier in Cremona.

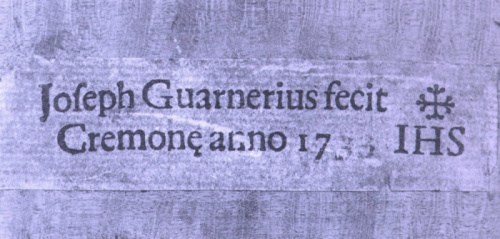

The label of the 1733 ‘Soil’ Guarneri. Photo: Peter Biddulph Ltd

The new label was used for the rest of Guarneri’s life. The short text reads simply: ‘Joseph Guarnerius fecit Cremonae anno…’ but it is mostly famed because on the right it bears the letters ‘IHS’ under a cross. It is not known why Giuseppe used this symbol, although it was quite common in the Catholic tradition at that time, but thanks to it, about 50 years after his death, he earned the nickname ‘del Gesù’. In 1816 Count Cozio wrote that there were two Giuseppe Guarneri makers, and the second used a label with a symbol referring to Jesus: in Italian ‘il bollo del Gesù’. As far as we know, during his life Guarneri had no nickname and he probably never imagined he would have one.

Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ had never been good with money, and we know that his health was declining. Whatever the reason had been for the son to leave his father’s house after his marriage, he never abandoned the old man. Their working relationship continued – seen in the last ‘filius’ cellos showing the hand of ‘del Gesù’ and the heads the father made for his son’s violins – and suggests they remained in close proximity, with the young master helping his parents in their difficult old age. The old Guarneris borrowed money from friends a few times, and when they settled their debts by selling a part of the family house in 1737, Giuseppe the younger was present. On the last day of 1737 ‘del Gesù’s mother died, and three days later, to pay the expenses for the funeral, his father obtained another loan.

Again the young Giuseppe was there, assisting his father, and if it is little surprise that ‘filius Andreae’ had run out of money, it seems curious that ‘del Gesù’ was also apparently unable to afford this expense. A few months after the loan ‘del Gesù’ went to the same lender to get more money, this time apparently to repay a debt he had with somebody else. Considering he was working at a good rate, as the existing violins indicate, this sounds odd. Perhaps he was acting on behalf of his father, as a reading of other documents suggests. In fact a nobleman made a deed in March 1740 and again ‘del Gesù’ was called to be there as a witness. It was not completely usual to find a working-class man in such a situation, and this again suggests he had a good reputation: he would surely not have been called if he was a man with economic problems, or if he was seen as dissolute or something similar.

The ‘Leduc’ of 1745 was perhaps one of the violins left unfinished after the death of ‘del Gesù’ in 1744. Photo: Peter Biddulph Ltd

Later in 1740, following the death of their father, ‘del Gesù’ and his brother Pietro of Venice sold the rest of the family house. Having repaid the debts their father had left, they shared what remained, apparently with an easy and friendly agreement. Four years later, the last four years of his wild genius as a maker, ‘del Gesù’ died in his home. His parish priest recorded in the death records that after receiving the holy sacraments and last rites he died ‘commending his soul to God’: this was normal behavior for a man of his time.

It is difficult to suppress the old romanticised picture of ‘del Gesù’ in his last moments, a crazy, impoverished maker with a wild-looking instrument still on his bench, but we should not hide the greatness of this maker in a cloud of legend. It is much more honest to try to understand him according to the facts we know, and appreciate his humanity side by side with his inimitable genius.

John Dilworth and Carlo Chiesa are among the world’s foremost makers, experts and restorers of fine violins. They helped co-write ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ alongside other books.

Coming soon: Alberto Giordano analyses what makes the Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ ‘il Cannone’ such a powerful violin.