Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ has long been seen as the most enigmatic and least understood of the great Cremonese masters. Amati, Stradivari and even Stainer achieved celebrity in their own times. Much information about them was retained in the general record, and the gradual reclamation of their lives and work has been a consistent building upon available materials. With Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, the process has been complex and, in the past, highly speculative.

He was after all, just the son of the second generation of one of the ‘supporting players’ in a city of geniuses. While Stradivaris and Amatis became the currency of the courts of Europe, Guarneris were more likely the working musicians’ option. There is little evidence of Guarneri instruments in the inventories of the great palaces. The first serious connoisseur of Italian instruments, Count Cozio di Salabue, took little interest in his work, damning it as ‘second rate’ and ‘poorly executed’ in 1816. He also made one of the earliest references to ‘del Gesù’s rumoured imprisonment, although he was doubtful about this rumor and made a note to check if it was true. With rather more authority, he stated that the maker’s work could be found easily for the cost of two or three zecchini each (a Stradivari would require ten or eleven, and a Nicolò Amati up to forty).

The earliest example of Guarneri’s fully independent work is the ‘Kubelik, von Vecsey’ of 1728. Photos: Peter Biddulph Ltd

![]()

Guarneri ‘del Gesù’s instruments remained largely within Italy until Nicolò Paganini’s first tour of Europe in 1828. Well aware of the expressive power of ‘del Gesù’, he dazzled audiences from Vienna to Strasbourg with his 1743 Guarneri, which he dubbed ‘il Cannone’ (ID 40130). After that, musicians, collectors and dealers fell over themselves in the hunt for more of Guarneri’s work, and it is interesting that it was for their tone, rather than their status, that the instruments of ‘del Gesù’ became sought after. But their rise in value, to the fantastical £10 million that the 1741 ‘Vieuxtemps’ (ID 40433) realised only recently, is based also on the comparative rarity of his work. A short life, not always focused on the vocation of violin making, has ensured that Guarneris are harder to find than Stradivaris or Amatis and this has given them a particular value and interest that goes beyond their intrinsic worth. By most estimates there are about 150 instruments extant; a poor figure compared with Stradivari’s production. Nevertheless, it equates to about ten instruments made in each of his 16 years as a craftsman; a fair and vigorous rate of work for someone who was once thought of as a dissolute jailbird.

As with many families of violin makers, defining the change in work from father to son is almost impossible. From the Amati family onward, sons (as far as we know, since the contribution of women to violin making in the classical period has not so far been discovered) provided assistance to the father in growing degrees of confidence and independence as they grew older, but as long as the father was alive, it was his label that was placed in the instrument. The son, however much he may have contributed to later work, could print his own label only after his father’s demise.

The c.1731 ‘Messeas’ cello clearly shows the hand of the younger Giuseppe despite bearing the ‘filius Andreae’ label of his father

![]()

Many late works by Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ do seem to show the younger Giuseppe’s hand. How to identify that hand is the trick. Two cellos are particularly helpful in this regard, both labeled Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’, one dated 1729 (ID 43989), and the ‘Messeas’ of c. 1731 (ID 40385), which carries the elder Giuseppe’s last known label. The earlier example shows a distinctive difference in the working of the back and front, suggesting that the front is the work of the younger man alone, perhaps finishing off an instrument left abandoned by his father. This leads to the ‘Messeas’, which carries many features of the earlier cello, but is clearly all made and completed by the same hand, that of the younger Giuseppe. So we can point to certain features that are unique to the son and distinct from his father. The earlier instrument has a high arched back, familiar from other works of ‘filius Andreae’, but the front is lower and flatter, the soundholes upright, broadly cut and widely set. The same soundholes appear in the ‘Messeas’, as well as an overall flatter arch on both plates. The ‘Messeas’ also has a very different scroll, narrow and quite Bergonzi-like, with a small, neat chamfer. These points are useful indicators of the workmanship of young Giuseppe, who was then aged around 30 and had probably worked as his father’s sole assistant for some 15 years.

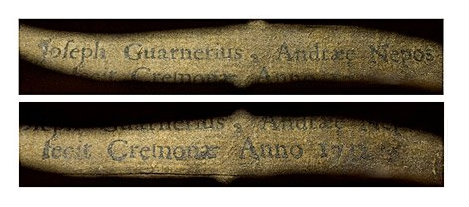

The 1728 ‘von Vecsey’ has the only known example of a genuine ‘Andrea Nepos’ label, which predates the famous ‘IHS’ one. Photos: Peter Biddulph Ltd

For the Guarneri family the question of labels became a particular issue, since both sons of Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ left the family workshop and worked independently during their father’s own life; Pietro in Venice, but the younger, Giuseppe Bartolomeo, close to home in Cremona itself. When the young Giuseppe separated from his father he also broke with tradition and had his own label printed, describing himself as ‘Giuseppe Guarneri Andrea Nepos’. Today only one genuine example is known, in the ‘Kubelik, von Vecsey’ violin of 1728 (ID 71858). This represents possibly the earliest example of his entirely independent work and is fully compliant with the style and forms seen in the cellos. When he established his own permanent workshop a few years later, identified by the ‘IHS’ motif, his work rapidly developed a new identity…

To be continued in Part 2, where we explore the experimental middle period of the newly dubbed ‘del Gesù’.

John Dilworth and Carlo Chiesa are among the world’s foremost makers, experts and restorers of fine violins. They helped co-write ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ alongside other books.