This week’s Carteggio features an excerpt from Dmitry Gindin’s new book The Modern Italian Violin Makers. Many of this book’s other chapters are based on articles originally published in Cozio’s Carteggio between 2015 and 2019 . The book can be pre-ordered here.

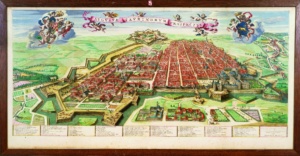

Throughout the centuries Turin has been one of Italy’s largest and most important cities, and remains so today. From early in its modern history, the Duchy of Savoy enjoyed strong ties to French nobility and ruling elite, while also suffering numerous invasions from and annexations to France. Turin became capital of the Duchy in 1563 and later of the Italian region of Piedmont. As in all major Italian cities, a significant and quite independent-minded violin-making school developed in and around Turin during the Baroque and early Classical periods.

The city’s earliest noteworthy violin making lay in the hands of Enrico Catenar (c.1620–1701), who came there from Franconia in Germany, and Fabrizio Senta (1629–1681), a native of Piedmont. The best-known and most prolific Piedmontese luthier of the classical period was Chiaffredo or Gioffredo Cappa (c. 1652–1717). Although he worked in Saluzzo, independently from makers in Turin, his earliest works recall the style of Senta, who may have initially inspired or even instructed him. Spirito Sorsana (c. 1670–c. 1740) worked in Cuneo, some 30km to the south. Stylistically, his fine work resembles Cappa’s but he appears to have been independent.

Back in Turin, Giovanni Francesco Celoniato (1676–1751) and his presumed pupil, Giovanni Battista Genova (1718–1776), were the final contributors to what may be termed the classical Turin school. In 1771 G.B. Guadagnini, who was to play a pivotal role in the further development of violin making in Turin and elsewhere, arrived here from Piacenza by way of Milan and Parma. Even prior to his move to Turin, Guadagnini had earned the status of best maker of his time, thanks to his talent, long experience and prodigious output in Piacenza, Milan and Parma. While Turin’s early luthiers showed some knowledge of the Amati school, Guadagnini brought with him the classical Cremonese model and method through his own convincing modifications. He died in Turin in 1786.

While Turin’s early luthiers showed some knowledge of the Amati school, Guadagnini brought with him the classical Cremonese model and method through his own convincing modifications.

Nineteenth-century Turinese violin making stemmed from two main sources: the descendants of Guadagnini on the one hand, and Giovanni Francesco Pressenda (1777–1854) on the other. Pressenda, a poor labourer from southern Piedmont, arrived in Turin around 1815 to join the workshop of French luthier Nicolas-Leté-Pillement (1775–1819). Giuseppe Guadagnini (1753–1805), the principal violin-making descendant of Giovanni Battista, mainly worked outside Turin, in Pavia, Como and Milan. His siblings who remained in the city, Gaetano I and Carlo, seem to have been far less assiduous in violin making than their predecessors; by the early-19th century, the Guadagnini shop had moved away from violin construction to concentrate primarily on guitars. With Gaetano II Guadagnini (1796–1852) fine violin making re-established itself in the family, albeit far more modestly than in the 18th century, as plucked instruments and dealing remained his main interests.

By the 1820s Pressenda worked in parallel to the slightly younger Savoyard nobleman and dentist, Alexandre D’Espine (1782–1855). Pressenda was to become the finest luthier in Italy and an inspiration to nearly all of Turin’s successive makers. Both Pressenda and D’Espine were intimately familiar with French production-line methods, but Pressenda was the first Italian maker since Nicolò Amati and Antonio Stradivari to master the delegation of tasks among his apprentices. From 1834 Giuseppe Rocca (1807–1865) joined Pressenda’s workshop and helped his master achieve an exceptional finished product. Alas, the beautiful instruments by Pressenda and Rocca would not bring either maker close to the kind of financial rewards enjoyed by their Parisian counterpart, Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume. By mid-century Pressenda and D’Espine saw their fortunes sour, and Rocca left Turin definitively in 1863 for Genoa, where he died destitute.

After Rocca’s departure, Turin’s violin making remained in the hands of the next generation of maker/dealers, Benedetto Gioffredo (1822–1888) and Antonio Guadagnini (1831–1881). Earlier in his career Guadagnini had built a small number of fine violins very much in the style of his father, while Benedetto Gioffredo sought to emulate Pressenda. After Pressenda’s death, Gioffredo had composed a rather fanciful pamphlet about the great maker, whose main objective was to more easily market instruments very similar to Pressenda’s that left the Rinaldi workshop bearing the great maker’s very convincing labels. The actual maker behind these instruments that have both fooled and puzzled experts for the last 150 years was his father-in-law, Pressenda’s friend and former workman Teobaldo Rinaldi (b. 1805), whose family name Gioffredo added to his, as seen on instruments labelled Gioffredo Benedetto Rinaldi. Both Gioffredo and Antonio Guadagnini, although in more modest ways, strove to replicate J.B. Vuillaume’s highly successful semi-commercial business model, with Guadagnini having left behind good evidence of his fine, semi-commercial production.

Italy’s post-Risorgemento industrialization led to renewed interest in musical performance in the main cities. The economic improvements ensured demand for the work of a few young, talented locals and others from Piedmont and elsewhere, echoing Turin’s violin-making past. The first well-known maker to arrive in the city was probably Enrico Clodoveo Melegari (1835–1895) from Parma, followed in 1874 by Enrico Marchetti from Milan. In the early 1890s, Gioffredo Benedetto Rinaldi’s nephew and successor, Romano Marengo (1866-1926), having earlier trained with Enrico Marchetti, began building new instruments, and from then on made them in significant numbers, progressively developing more commercial means of production, while competing with other superb emerging makers, as well as the last members of the Guadagnini clan.

In 1905 the Teatro Regio reopened, following a four-year renovation, with an auditorium of about 3,000 seats. Strong industrial progress in northern Italy led to Fiat and Lancia, the two leading Italian car manufacturers, being established in Turin between 1899 and 1906. By 1911 Turin had grown to over 430,000 inhabitants, making it one of Europe’s largest industrial cities. Its contemporary violin making scene was thriving.

The Last of the Guadagninis: Francesco (1863–1948) and Paolo (1908–1942)

When Antonio Guadagnini died, his sons Francesco (1863–1948) and Giuseppe II (1866–c. 1903), were 18 and 15 respectively. The brothers inherited the Guadagnini shop as teens, along with their father’s business acumen. They also were to produce plucked instruments, in addition to restoring and dealing. Francesco did not take his inheritance lightly and throughout his productive career did his best to maintain the family’s violin-making standards and traditions. Like most of his predecessors, Francesco had a good knowledge of violin making, as the more obscure Giuseppe II did as well. Until about 1897, Francesco collaborated with Giuseppe; one encounters, on rare occasion, instruments of various grades labelled ‘Guadagnini Brothers, Francesco and Giuseppe, sons of the late Antonio’.

Like Enrico Marchetti, the Guadagnini brothers exhibited instruments both nationally and internationally, starting in 1884, when they received a silver medal at the Turin Universal Exhibition. In 1885 they exhibited two guitars and a string quartet in Antwerp, and in 1892 Francesco won a gold medal in the Vienna Exhibition.

Francesco married Maria Barovero in 1897. By 1898 the family shop was renamed ‘Guadagnini Francesco – fu Antonio’, as Giuseppe II was no longer mentioned as part of the Guadagnini business. That year, Francesco entered the Turin Universal Exhibition and did so again in 1911. In 1916 at the Rome Exhibition he won a silver medal, and in Cremona’s famous 1937 Bicentenary Exhibition he presented a string quartet.

By the mid-1920s, Francesco’s son Paolo (1908–1942) began to assist, while apparently also receiving advice from Annibale Fagnola. Francesco became the last surviving, albeit by then inactive, violin maker of the Guadagnini dynasty, as Paolo died in the bombing of his transport ship during the Second World War. Six years later Francesco died, aged 85, ending that clan’s nearly 250-year history.

The Work of Francesco and Paolo Guadagnini

Apart from Antonio Guadagnini’s very early production, which is very much in the style of his father Gaetano’s, most of his

known instruments have much in common with the fine French lutherie of the period; the young Francesco and Giuseppe II continued Antonio’s way of working that likely included the employment of others’ skills. This business model, although using local makers, was also adopted by Benedetto Gioffredo and Romano Marengo. Meanwhile, Francesco Guadagnini’s early work demonstrates his fine ability as violin maker and bears a strong resemblance to the later instruments of his father. Francesco continued to make fine plucked instruments, especially guitars, in the tradition of his forebears, a skill he was to pass on to his son.

Francesco would have developed a violin-making reputation to match his historical importance had he maintained the quality produced by his shop until around 1910. Today, however, we are mostly familiar with the instruments of his final period, which began while his competitors were producing some of the finest instruments of their careers, indeed the best to come out of Italy overall since the mid-19th century. Fagnola, Oddone and Guerra were more talented than Turin shopkeepers like Francesco Guadagnini and Marengo-Rinaldi, though they lacked established family names and businesses.

These circumstances may have impelled Francesco Guadagnini and Romano Marengo to start making instruments on their own. Now middle-aged, Francesco needed to capitalise on the family name; he thus created a charming model that captured the spirit of the Turin-period instruments of his great ancestor, Giovanni Battista. Francesco’s flat and simplistic model was conducive to quicker production. This differentiated him from his rivals, most of whom tried their hand at copying G.B. Guadagnini but without great success, preferring to develop models based on Pressenda and Giuseppe Rocca.

At their best, Francesco’s later instruments, now displaying the hand of Paolo (whose rare personal work is nearly identical), are vigorously unpretentious and direct with a flat, bold and unlaboured arching, perfectly positioned, slightly slanting but cleanly cut f-holes, and neat, clear purfling, laid without any channelling and ending rather abruptly at the short and stubby corners. The varnish is generally red-brown (either bright or opaque), hard and usually thin, although it varies in quality from attractive to quite poor; the edges of the scrolls are blackened and have the pronounced centre scribe line; the backs, often of pretty wood, have round, light-coloured pins – both standard characteristic of the classic Turin school since Giovanni Battista Guadagnini. Francesco retired as a maker just before the Second World War.

Dmitry Gindin is an expert, consultant and was an original founding partner of Tarisio.