It is clear that Giovanni Battista Guadagnini had a pretty original cast of mind. It seems accepted these days that he was a self-taught maker: there is nothing in his known biographical history that connects him to any practising luthier, and nothing in his working techniques that allies him to any particular school of making. In fact, in each successive city where he worked, he came to define the contemporary school of violin making through his own prolific output and that of his family and pupils. His designs for violin, viola and cello are all highly original and for the most part extremely effective, and it is perhaps in his cellos that this is most evident.

In the historical context it is not difficult to see a naturally gifted woodworker being able to pick up the techniques of violin making. The materials (including varnish no doubt) would have been in common circulation, good instruments were available to observe and imitate, and the tools easily made. But to make instruments that work well, the help of a player or the ability to play oneself is essential; no one can successfully work ‘blind’ in this way.

Francesco Alborea helped to establish the superiority of the cello over the viol in the late 17th century

Given Guadagnini’s humble farming background, as described in Duane Rosengard’s groundbreaking book (which also demonstrates that the maker was illiterate all his life) it is unlikely that he himself was a trained player. [1] How many of the 18th-century makers were players, or how far the practice of music would have been part of their training, is unknown. Gasparo ‘da Salo’ worked as a bass player and Pietro Guarneri of Mantua was certainly a violinist, but beyond that it is guesswork. In the distant origins of the profession of music making, players would of necessity have been makers of instruments also. But when musicians and patrons were able to commission specialist craftsmen, instrument making became a clearly defined and separate occupation.

Guadagnini was supported for much of his life by wealthy patrons – the Marquis Guillaume de Tillot, the Duke of Parma and Count Cozio di Salabue – but to reach the required level of professionalism to attract a patron he would first have needed personal clients to forge a reputation. We do know, thanks to Rosengard’s research, that he associated closely with his working customers, the players. And that possibly is the key to his work in the development of the cello.

Rosengard’s book supplies us with many names of musicians with whom Guadagnini associated throughout his life. In Piacenza these included Nadotti, Opici, Zenzalari, and later Domenico Antenari. Most relevant to the topic in hand, though, are the Ferrari brothers, Paolo and Carlo. Paolo was a violinist and Carlo a cellist. A considerable cellist too: considered a leading virtuoso and innovator, and credited with introducing the thumb position to Italy, he was an ideal collaborator for Guadagnini.

In musical terms, the 18th century was a transformational period for the cello in Italy. Domenico Gabrielli first published solo music for it in Bologna in 1689. Possibly the first celebrated cello soloist, Franciscello (Francesco Alborea) of Rome, finally established the superiority of his instrument over the viol at the close of the 17th century. Its modern role as a front-rank instrument was confirmed with the emergence some 50 years later of Luigi Boccherini, whose great works for solo cello defined it as far more than just an accompanying voice.

Carlo Ferrari was a considerable cellist: considered a leading virtuoso and innovator, and credited with introducing the thumb position to Italy, he was an ideal collaborator for Guadagnini

This all triggered changes in the design of the cello itself. Gradually the great bass instrument of the 16th and 17th centuries, with its back length of over 790 mm, shrank in order to meet the increasingly virtuostic needs of the players, who required a new voice with a stronger focus in the upper register. Francesco Rugeri and Antonio Stradivari are seen as the pioneers of this; Stradivari’s celebrated B-form design of around 1710 was the template for the modern concert instrument, laying down the size and proportions that are still adhered to today, with a powerful low arch that gives force and projection to the upper strings. It is from this point that Guadagnini developed his own designs for the instrument. He continued the general reduction in size but, most significantly he also reversed the trend towards lower, flatter archings.

Almost all his work is, to me, ‘player friendly’; that is, for playing under modern conditions. His violins have a streamlined shape, with gently sloping upper bouts giving freedom to the left hand. His violas are mostly of accommodatingly small size. The cellos, likewise, are most obviously tailored to suit the player, with little acknowledgement of traditional designs.

Piacenza

Guadagnini’s career began in Piacenza in about 1742, and in the years up to 1748 he produced a surprisingly large number of cellos; at least ten cellos or parts of cellos originate from just these six years. This impressive output is presumably some indication of Carlo Ferrari’s influence. One striking aspect of these instruments is that they are all built on one of two original and short models; there is no empirical progression from one form to another, and no obvious prototype. Guadagnini used the two forms simultaneously, one of about 740 mm length and the other of around 715 mm. This is quite a dramatic reduction from the general standard of the time, considerably shorter even than Stradivari’s 756 mm B form. To look for any precedent you have to go to Brescia, where G.B. Rogeri worked to a 730 mm model at the beginning of the century.

‘I just love it – it has such wonderful colors in all the different registers and it’s very responsive. It’s made a huge difference to my playing. I think I became a much better cellist after I got it.’

– David Waterman on his Guadagnini cello, Piacenza, 1745

Guadagnini’s larger model is also a good 10 mm wider in the upper and middle bouts than the Stradivari B form, and in this way somewhat resembles a Montagnana. However, the middle and lower bouts are considerably reduced. The lower bouts of the large Guadagnini model measure at most 434 mm, while the smaller model is about 420 mm. This is smaller than the Stradivari B form’s 437 mm and the average Montagnana, which extends to 445 mm or so. What sort of instrument Carlo Ferrari himself actually played is not known and how Guadagnini arrived at his highly individual model can only be speculation, but it must surely have resulted in some way from discussion between the friends. Given Piacenza’s proximity to Cremona, it might be assumed that Ferrari played an Amati, a Strad or a Guarneri, and these instruments would have been the familiar models. But the influences at work in Guadagnini’s work are clearly very different.

The ‘Kohner’ of c. 1743 is a characteristic first-period cello from Piacenza made on the slightly larger model (733 mm back length, and widths of 352 mm, 239 mm and 434 mm). The ‘Ngeringa’, attributed to the same year, is of the smaller pattern (716 mm back length, and widths of 340 mm, 228 mm and 423 mm). To my eye there is much of the Montagnana about both these instruments; Montagnana was still working in Venice at this time, and his reputation as a cello maker would not have escaped Guadagnini. The soundholes are very Amatese, in similar manner to the typical Montagnana ‘f’, with a slender, upright stem and large, prominent circular finials, set quite closely together at the upper end. The rounded C bouts and slightly square projecting corners also have an air of Montagnana about them.

The spectacular 1757 ‘Teschenmacher’, made in Milan. Photos: Jan Roehrmann, ‘G.B. Guadagnini’, Edizioni Scrollavezza & Zanrè 2012

There is an even closer relationship in the form of the scroll, which has a Staineresque extended turn behind the eye, like those of Montagnana. Guadagnini’s cello scrolls are stylistically quite different from his violin heads. They almost invariably show this extended final turn reaching up behind the eye, and overall a rather slender form compared with the extravagance and breadth of the violin heads. It is certainly interesting that Guadagnini’s cellos seem to start from a different stylistic origin to his violins, and move only slowly towards a fusion of two differing ideals. In other words, he approached the two instruments as having quite separate identities.

Milan

In 1745 Carlo Ferrari moved to Milan. Only two more cellos are reliably attributed to Guadagnini’s remaining time in Piacenza, and in 1749 he followed Ferrari to Milan. There he began possibly his most fruitful and artistically complete period of violin making. His violins in this period from 1749 to 1758 are the most exuberant and richly varnished. The cellos seem to be restricted to the smaller form, however, with a 715 mm back length. Their soundholes no longer have the large upper circle and seem to conform more to his violin pattern, moving further apart on the table and also developing the remarkable oval-shaped lower hole, a distinguishing point of Guadagnini’s work. The Montagnana-like scroll continues, however, standing apart from the characteristic violin design with its shortened last turn and widely projecting eyes. Oddly too, the prominent pin-prick markings that almost invariably encircle the last turn and eye of his violin scrolls, very rarely appear on the cello heads.

David Finckel with his Guadagnini

‘The most extraordinary thing about my Guad is its unforgettable voice, which has such a human quality to it that when I play the cello I feel that I myself am singing. It seems to know how to shape the sound around a phrase instinctively. I also think of Casals when I play this cello, as he used to enjoy playing on it during the lessons he gave to its previous owner, a gentleman from Puerto Rico.’

– David Finckel on his Guadagnini cello, Milan, 1754

At least six great cellos come from this period, including the 1754 ‘Gerardy’, illustrated by Doring in his seminal 1949 book on Guadagnini, [2] as well as Rosengard, and the ‘Teschenmacher’ of 1757, illustrated by Scrollavezza [3] and featured in the 2011 Guadagnini exhibition in Parma. The ‘Gerardy’ shows the kind of wood that is familiar in much of Guadagnini’s previous work: handsomely figured, but flawed with prominent sap marks and small knots. The ‘Teschenmacher’ by comparison is spectacular, with flame majestically sweeping down from the center joint, which somehow emphasises the similarity to a Montagnana that has been reduced across the lower bouts. The rounded C bouts, protruding corners and sloping upper bouts and a marked flatness across the lower block all contribute to the effect.

Parma

From Milan, Guadagnini again followed his friend Ferrari to Parma, where his work seems to have declined a little, leaning toward affectation in some aspects. Typically his Parma violins have elongated soundholes, with the nicks set low and the stop length therefore increased. The varnish is usually less vividly tinted than in Milan and the arching tends to grow both on violins and cellos into an exaggerated peaked form. This in fact suits the larger instrument better than the violin. Another six cellos at least derive from this period. The Chi Mei Foundation’s instrument of 1762 and the ‘Leyds’ of 1764, both illustrated in Rosengard, are typical examples. The wood is more modest than that used in Milan and is less well illuminated by the slightly duller varnish.

The 1762 Guadagnini owned by the Chi Mei Museum is one of at least six cellos made during his time in Parma

Turin

With the death of his patron, the Duke Don Felipe in Parma, Guadagnini was ultimately forced by circumstances to leave the city in 1771, and for the first time his connection with Carlo Ferrari was broken. Ferrari remained in Parma until his death in 1789, while Guadagnini settled in Turin, where he found new contacts and patrons. Musically, Turin was the home of the great violinist Pugnani and a school of playing engendered by him. Guadagnini’s output reflects this, with far more violas and violins made in this last period than cellos. The outstanding representatives from Turin are the 1772 ‘Popper’ and 1777 ‘Simpson’. They are quite similar, although the ‘Popper’ is made of spectacularly figured poplar and the ‘Simpson’ has a back of Italian ‘oppio’ maple. They both illustrate the tendency to an increase in height of the arching and a reduction in the corners. The full arching compensates for the reduced air volume of the smaller instrument, and the corners, mere obstacles to the bow from the player’s perspective, become almost vestigial.

The ‘Simpson’ is perhaps the perfect player’s instrument with every square inch of space devoted to tone production and ease of playing. The arching springs full from the edge, memorably described to me by the luthier Joseph Grubaugh as looking like an ‘overinflated bald tyre’, almost Brescian in appearance. The upper edges fall away quickly from the neck, giving great freedom of movement for the left hand. It is marvelously compact, a great soloist’s instrument, now appropriately in the hands of Natalie Clein.

The c. 1777 ‘Simpson’, which dates from Guadagnini’s final Turin period, is marvelously compact and perhaps the perfect player’s instrument

In Turin Guadagnini was contracted to Count Cozio between 1773 and 1777 to sell him all his work. This gave Cozio an influence over Guadagnini with which he seems to have been ill at ease. It brought Cozio 57 instruments in all, including these two cellos and one unfinished one that was later passed to the Mantegazzas for completion – an astonishing body of work in so short a time. Cozio’s agenda was to revive the spirit of Stradivari in Italy, and to that end encouraged Guadagnini to adopt more Stradivarian inflections in his style. This is seen in the ‘Simpson’ only as the band of black ink around the chamfers of the scroll and the shortened terminus of the volute, but here at last there is a congruence between the heads made by Guadagnini for both violins and cellos. Guadagnini’s sons, Gaetano and Giuseppe, by now had an increasing role in the workshop, having reached their 20s. Their individual hand is hard to trace, particularly in the cellos, but Gaetano inherited the business on his father’s death in 1786. The Guadagnini shop continued for a remarkable three further generations, but the phenomenal series of cellos made by Giovanni Battista was never revisited or re-examined. Of his sons and grandsons, only Giuseppe seems to have made a cello with any similar flair and character.

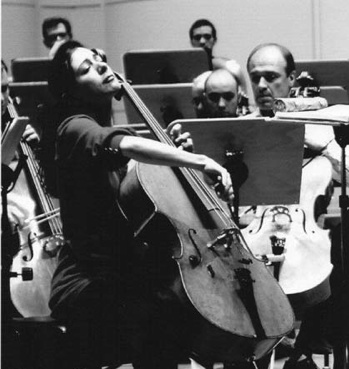

Natalie Clein plays her Guadagnini

‘It’s a great companion that never lets me down. We’re very well suited because I’m a physical person and a physical player, and I love the sensuality of playing it. I always think of its sound as a strong beam of light… being beamed across the stage into the hall.’

– Natalie Clein on the ‘Simpson’ Guadagnini, Turin, 1777

Technically there are several points of interest in Guadagnini’s cellos. One striking aspect is that the front very frequently measures larger all round than the back, and the outlines vary considerably between the two plates. The reason for this must lie in the construction. Although it is fairly certain that Guadagnini used a mould (there are violin forms identified in inventories of his possessions), it seems as if he fitted the back linings and possibly the back itself before removing the mould; the back is always much more consistent in outline, while the most deviation is seen in the middle bouts of the fronts. The upper linings would have been fitted afterward, while the whole structure had deformed slightly, the upper linings themselves also applying a certain expanding pressure. Deformations in the arching of the back are visible in many of Guadagnini’s cellos and violins, and I am convinced that he must have used fairly green, unseasoned wood. It is fascinating to read in Rosengard’s account that in 1775 Guadagnini was in contact with Paolo Stradivari, wanting to know of a wood supplier in Brescia. By 1776 he was unable to pay for his wood and was pressing Cozio to settle the bills. Given the rate that he was using up his wood (providing over 50 violins in four years) it cannot have rested long on the shelf to season.

Everything about Guadagnini’s work speaks of momentum, a forward energy that brought about a fluid variety of forms and ideas. Propelled by the demands of his clients at every stage, whether aristocratic patrons or working musicians, he worked quickly and without fuss. Sandpaper was certainly a valuable tool for him, and finishing of scrolls and broad surfaces did not detain him long (Cozio actually provides instructions for making sandpaper in his essays on violin making, gleaned perhaps from Guadagnini or his other chief informants, the Mantegazzas). But when the pressures and demands drive a strong craftsman’s hand, the results, as with these great cellos, can be spectacular.

John Dilworth is a maker, writer and expert. He has written extensively about fine instruments and their makers, and is a co-author of ‘The British Violin’, ‘Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu’ and ‘The Voller Brothers’ among other books.

Notes

[1] Giovanni Battista Guadagnini, Duane Rosengard, Haddonfield, New Jersey, 2000

[2] The Guadagnini Family of Violin Makers, Ernest N. Doring, William Lewis & Son, Chicago, 1949

[3] Joannes Baptista Guadagnini, Edizioni Scrollavezza & Zanrè, 2012