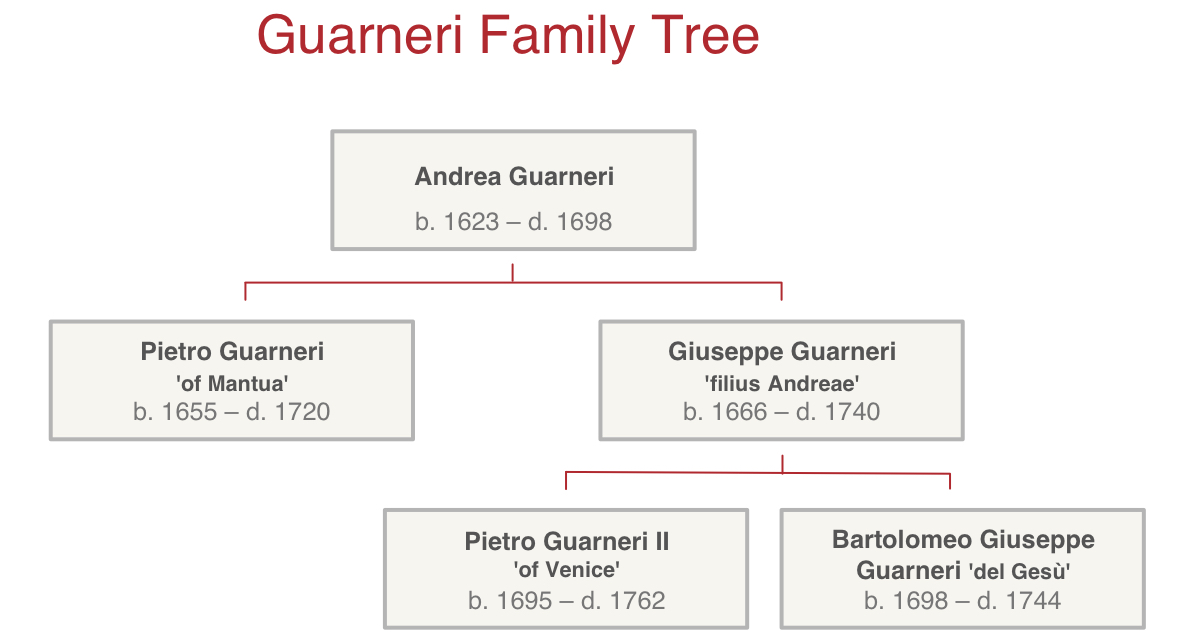

Giovanni Battista Giuseppe Guarneri (known as Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’) was born 350 years ago, on November 25, 1666,[1] to Andrea Guarneri and Anna Maria Orcelli, in the parish of San Matteo in Cremona. A few years earlier his father had left the workshop of Nicolò Amati, but he continued to follow the Amati style. He had established the Guarneri workshop on Piazza San Domenico, opposite the church of the same name, and was helped by his eldest son, Pietro. Business was apparently good: Andrea had connections with musicians, including a cousin of Anna Maria Orcelli, Andrea’s wife, who was a professional violinist, and noble amateurs. Indeed, the little Giuseppe was the godson of the Marquis Giovanni Battista Ariberti, who was a patron of Cremona’s only theatre and whose son, Bartolomeo Ariberti, was later to commission Antonio Stradivari to make a quintet of instruments for the Grand Duke of Tuscany.

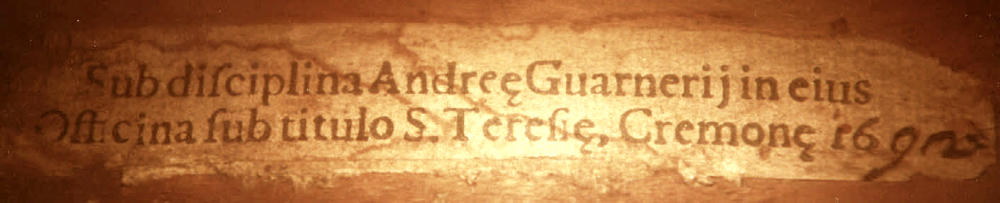

The 1689 ‘Quarestani’, which shows the young maker’s inexperience, but also some of the hallmarks of his mature style. Photos courtesy of the Museo del Violino, Cremona

More photosIn 1677 Pietro married Caterina Sussagni, but he continued to live in the family home. Young Giuseppe probably entered his father’s workshop at this time. Over the next few years a number of circumstances combined to increase local competition for the Guarneri workshop. Firstly, Girolamo Amati II, the son of Nicolò, had joined his father in the Amati workshop. Secondly, a promising young violin maker named Antonio Stradivari was emerging, who in 1680 moved his workshop to the Piazza San Domenico, just a few metres away from the Casa Guarneri. Perhaps in part because of this increasing local competition, Pietro moved to Mantua around 1680, where he became a violinist at the court of the Gonzaga family and a dealer of strings as well as making violins.

The young Giuseppe was now active as a maker and from around 1685 we start to see his hand in Andrea’s instruments, particularly in the heads. It is possible that at this time Andrea was suffering from health problems, as in 1687 he made the first of three wills.[2] The first surviving instruments made entirely by Giuseppe date from 1689. In the ‘Quarestani’ violin of that year, which bears the original label of his father, the inexperience of the 23-year-old Giuseppe shows in the very high and pointed arching. Yet there are also some features that were to become distinctive characteristics of his work, including the narrow scroll, showing gouge toolmarks and no trace of scrapers or abrasives. In addition the corners are smaller than those of his father, with flatter, shallower curves leading into them from the upper and lower bouts. This kind of corner was typical of his work throughout his life. His varnish is very similar to Andrea’s, although with a slightly thinner consistency, its color tending to deep brown.

The year after the construction of this violin, Giuseppe married the young Barbara Franchi, a parishioner of Sant’ Agata,[3] who then joined the Guarneri family in the house on Piazza San Domenico. In the meantime the health of Andrea seems to have further declined, as he made two further wills within a few years (1692 and 1694), thereby increasing his son’s responsibility in the running of the family workshop.

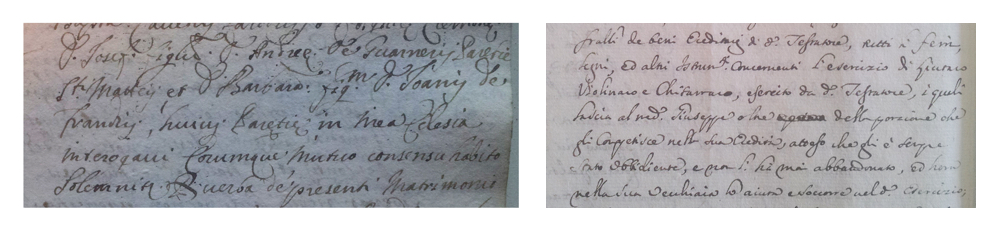

Records of the marriage of ‘filius Andreae’ to Barbara Franchi in 1690 (left) and Andrea’s will of 1692, in which he praises his son’s loyalty

In 1692 Giuseppe made three cellos and almost all subsequent cellos made in the Guarneri workshop appear to have been his. This was probably another sign of his father’s poor health. These three instruments also show the first attempts by the Guarneri family to break away from the ideas of Nicolò Amati by creating a smaller cello with lower arching, thereby anticipating Antonio Stradivari by about 10 years.

Nicolò Amati had died in 1684 and the workshop had passed to his son, Girolamo II. Girolamo was not, however, much of a threat to his competitors because although his instruments did not lack quality, the production of the Amati workshop after he took over declined for a variety of reasons. By contrast, Stradivari had become a universally renowned maker. During these years Giuseppe Guarneri’s burden of responsibility, both professionally and personally, must have increased substantially and his financial circumstances were constantly precarious – on occasion he also worked as a violinist, which was perhaps necessary to supplement his income from violin making.[4] His support of the workshop and the family was expressly recognized by Andrea in his second will, in which he wrote that Giuseppe ‘gli è sempre stato obbidiente, e non li ha mai abbandonato, ed hora nella sua vecchiaia lo aiuta e soccorre’ (he has always been obedient to him, and has never abandoned him, and now he helps and supports him in his old age).[5]

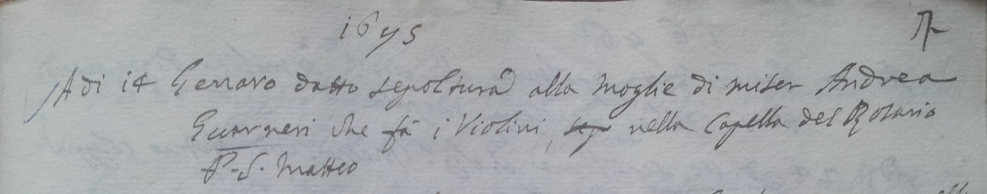

Anna Maria Orcelli, the wife of Andrea, died on January 14, 1695 [6] and her young daughter-in-law Barbara Franchi, who was expecting a child, became the matriarch of the family. A few months later, on April 14, Giuseppe and Barbara’s fourth child was born, named Pietro perhaps in honor of his uncle in Mantua. By 1698 the health of Andrea Guarneri appears to have worsened, as in August of that year the aged violin maker arranged the distribution of his estate between his two sons. Pietro was in Cremona at this point [7] and on August 21, 1698 the two brothers went to the notary Porro to draw up an agreement in which it was stated that the entire workshop would remain in the hands of Giuseppe, as Andrea wished, in exchange for 600 lire paid to his brother Pietro.[8] On the same day Barbara Franchi gave birth to a child, Bartolomeo Giuseppe, who was immediately taken for baptism by his uncle Pietro, who became his godfather. No one could have imagined it then, but that child would become the famous Guarneri ‘del Gesù’, with a talent to rival that of Antonio Stradivari.

The 1695 burial record for Anna Maria Orcelli, which describes her as the ‘wife of Andrea Guarneri who makes violins’

All five violin makers of the Guarneri family were therefore gathered under the same roof on August 21, 1698: the father, Andrea, his sons Pietro (‘of Mantua’) and Giuseppe (‘filius Andreae’) and his grandsons, Pietro (‘of Venice’) and Bartolomeo Giuseppe (‘del Gesù’). It was the first and probably the last time they were all together, as Andrea Guarneri died just a few months later, on December 8, 1698, and was buried next to his wife in the Rosary Chapel, in the church of San Domenico.[9]

All five violin makers of the Guarneri family were gathered under the same roof on August 21, 1698 – it was the first and probably the last time they were all together

It took Giuseppe ten years to settle his brother’s inheritance from his father. Cremona was by this time experiencing one of its most troubled periods. Involved in the War of Spanish Succession, the city was besieged by Austrian troops and was finally captured in the Battle of Cremona in 1702, when Prince Eugenio of Savoy, the commander of the Habsburg troops, stormed the city. Through all of this, Giuseppe continued his work. There was no doubt that the competition from Stradivari was strong, but he was shrewd enough to understand that the era of the Amati and their ideas was over and that this great new violin maker was outlining new, forward-looking concepts. Up until the death of Andrea, Giuseppe had followed the pattern that he had inherited from his master, but once free from the constraints imposed by his elderly parent and strongly influenced by Stradivari, he began to change his style.

The 1703 ‘Compte de Narp’ violin by ‘filius Andreae’. Photos courtesy of Dr Anna Wong, Hong Kong

More photosAround 1705 he introduced a new violin model with a wider upper bout and a narrower middle bout that is distinctively squarish in shape. He also changed the soundholes from the short and sinuous Amati style to a longer and more rigid design. This was his most successful model, and it appears to have influenced Carlo Bergonzi and other Cremonese makers up to Enrico Ceruti, whose model incorporates similarly squared C-bouts. Although the model was innovative, Giuseppe’s finances did not improve, but instead deteriorated further. In 1715 he had to ask a neighbour, the blacksmith Leonardo Rolla, for a loan of 1,000 imperial lire.[10] Giuseppe carried this debt with him for the rest of his life but, despite this, he usually managed to acquire high-quality wood, both for the maple and the spruce.

From around 1715 some instruments show the hand of his son Pietro although Charles Beare has written of seeing ‘only one in which I felt it could be detected through and through, and that was the superb instrument belonging twenty years ago to Arthur Grumiaux, which I have since lost track of.’ [11] Unfortunately Pietro’s involvement in the workshop was short-lived – in December 1717 he left Cremona permanently to settle in Venice. Giuseppe ‘filius Andreae’ therefore continued to run the workshop with the help of the young Bartolomeo Giuseppe.

The hand of the youngest son in his father’s instruments is discernible from around 1720. However, this collaboration was also apparently short-lived. On October 3, 1722 in the parish of San Pantaleone, Bartolomeo Giuseppe married Caterina Rota, the daughter of an Austrian imperial soldier, ‘Germana ex civitate Viennensi’ (German from the city of Vienna).[12] For the next six years the couple’s names do not appear in any Cremonese documents, the parish census, or in any other ecclesiastical or notary acts. It seems likely therefore that they had moved away from Cremona, although we have no evidence as to where they were or what Bartolomeo Giuseppe was doing to earn a living until 1729, when he reappears in the Cremonese records.

Perhaps Bartolomeo Giuseppe had found employment in another workshop outside Cremona. Certainly one of his earliest surviving instruments with an original label, the ‘Baltic’ of c. 1731, shows many stylistic differences to the instruments made by his father. It has also been suggested that many of his working techniques from 1731 were also different from those he would have been taught in his youth. As Andrew Ryan has hypothesized, there is evidence to suggest that he laid out the position of his soundholes from the outside of the instrument, unlike his father and other Cremonese violin makers before him, who traced the ƒ-shape from inside the table.[13]

‘Filius Andreae’ therefore remained alone in the workshop and in 1729, presumably due to continued financial difficulties, he decided to rent out a part of his house. By the following year his health had declined so much that in the parish census of 1730 he is absent because he was hospitalized.[14] He was back at home by the time of the 1731 census, but was now incapable of working. As we have seen, it is around this point that Bartolomeo Giuseppe reappears in the Cremonese records. In fact 1731 appears to be the last year in which we see the original label of ‘filius Andreae’ and it seems that almost all of these instruments were finished by his son; it is also the year of the first surviving Bartolomeo Giuseppe label with the ‘IHS’ symbol, which led to his famous nickname. However, ‘filius Andreae’ continued to assist ‘del Gesù’, particularly in the carving of the heads between 1731 and 1739. Unfortunately the family’s economic fortunes did not recover and in July 1737 ‘filius Andreae’ decided to sell a part of their house.[15]

The 1735 ‘Plowden’ by ‘del Gesù’. Heads on ‘del Gesù’ violins from the mid-1730s often show the hand of ‘filius Andreae’

A few months later, on December 31, 1737, Barbara Franchi died and was buried in the family tomb in San Domenico (in the same chapel in which Antonio Stradivari had been buried 13 days earlier).[16] The economic situation was so desperate that ‘filius Andreae’ had to ask the dealer Antonio Galanti for a loan of 600 lire in order to pay for the funeral.[17] Unable even to honor this debt, on December 11, 1739 he returned yet again to Galanti for another loan.[18] This is the final legal document in which we see Giuseppe Guarneri ‘filius Andreae’ alive. It is symbolic that after all his economic vicissitudes, the last act of his life was a contract for yet another loan that he would never manage to pay back.

In the Easter census of 1740 ‘filius Andreae’ was no longer present in the family house and in May of that year his sons agreed to sell the remaining portion of the house and thereby pay off all debts inherited from their father.[19] Although researchers have scoured the archives of Cremona, no one has been able to find the act of burial of this violin maker. It is likely that he died in early 1740 in one of the city’s seven hospitals. It is nevertheless strange that he was not buried in the family tomb in San Domenico – perhaps he died out of town or of a contagious disease.

Despite being a contemporary of Antonio Stradivari, whose work overshadowed everything and everybody, Giuseppe Guarneri ‘filius Andreae’ was of fundamental importance in the history of violin making. In particular, as his instruments attest, he was the bridge between the style of Nicolò Amati and the great personality of his son Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri ‘del Gesù’.

A maker and restorer, Claudio Amighetti teaches at Cremona’s international violin making school.

Notes

[1] The original document has been missing from many years, but a picture is reproduced in the book by William H. & Arthur F. Hill, The Guarneri Family, Fakenham, 1931, p. 47.

[2] State Archive of Parma, notarile, f. 13010, June 11, 1687.

[3] Parish archives S. Agate, Matrimoniorum 1683–1703, p. 20.

[4] State Archive of Cremona, notarile, f. 5696, June 5, 1693.

[5] State Archive of Cremona, notarile, f. 6298, July 11, 1692.

[6] Diocesan Archive of Cremona, Libro de’ Morti di S. Domenico, 1682–1796, p. 7 ‘given burial to the wife of Mr. Andrea Guarneri who make violins’.

[7] It is unclear whether this was the first time Pietro had returned to his home town since his departure nearly 20 years before, but there is no documentary trace of him in Cremona between 1680 and 1697.

[8] State Archive of Cremona, notarile, f. 6303, August 21, 1698.

[9] Diocesan Archive of Cremona, Libro de’ Morti di S. Domenico, 1682–1796, p. 8.

[10] State Archive of Cremona, notarile, f. 6057, n. 144.

[11] Charles Beare, ‘Guarneri del Gesu’s Place in Cremonese Violin-making’ in Joseph Guarnerius, Cremona, 1995.

[12] Diocesan Archive of Cremona, Libro matrimoni di s. Pantaleone, 1595–1748, p. 124.

[13] Andrew Ryan, ‘The f-holes of Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu, thinking outside the box’, in Cremona 1730–50, The Violin Makers of Cremona, Liuteria Cremona, 2008.

[14] Diocesan Archive of Cremona, parish of s. Matteo, Libro del stato dell’anime 1723–1739.

[15] State Archive of Cremona, notarile, f. 6138, n. 370.

[16] Diocesan Archive of Cremona, Libro de’ Morti di S. Domenico, 1682–1796, p. 36.

[17] State Archive of Cremona, notarile, f. 6965, January 2, 1738.

[18] State Archive of Cremona, notarile, f. 6942, December 11, 1739.

[19] State Archive of Cremona, notarile, f. 6334, May 24, 1740.