In the spring of 1838 Giuseppe Antonio Ceruti packed up his family and moved to Mantua. In doing so he was severing his connection with the city of his upbringing, Cremona, already fabled as the birthplace of violin making in Italy. Furthermore, there is no indication that he ever returned to that city.

This information has not previously been known. Indeed, according to Duane Rosengard, whose research into the Ceruti violin makers has underpinned our understanding of their activities, the sources of information in Cremona have been maddeningly vague and imprecise. It had seemed as though the counterpart resources in Mantua were similarly vague – that is, until my last excursion through the archives of that city.

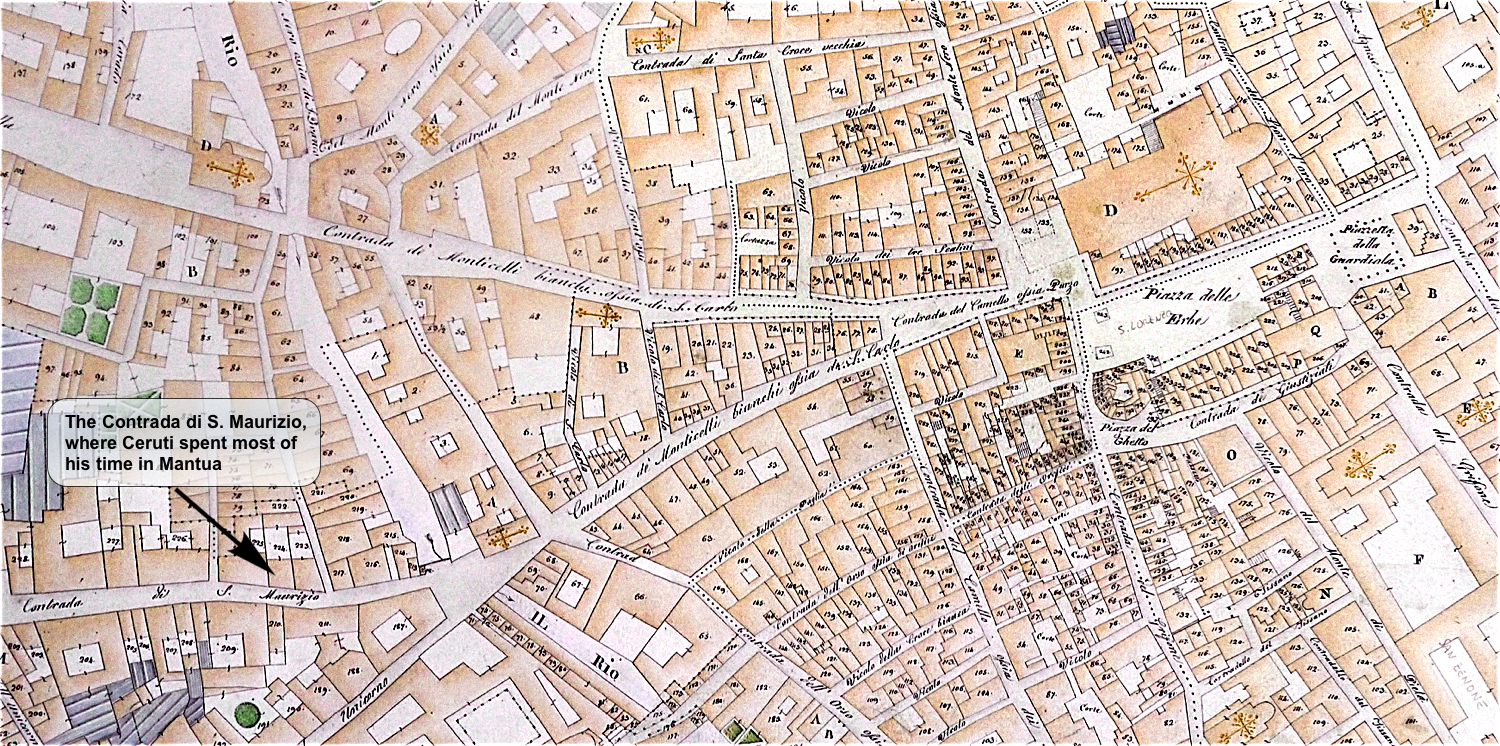

Map of Mantua from the 1820s. Ceruti lived from 1843–47 on the via Chiassi, near the church of S. Maurizio, then from 1847–50 further down the street near the church of San Barnaba

The difficulties stemmed from the political circumstances of the time. Both Cremona and Mantua were by this date ruled by the Austrians, whose record-keeping there left a fair bit to be desired. However, in Mantua there was a strong popular desire for Italian independence, and so the authorities followed a practice that allows us some insights. Starting in 1830–32 the police began to take a regular census of the population, which was continued after Mantua joined the Kingdom of Italy in 1866.

For our purposes, the census provides not only the basic information about each individual but also their residency status. The main volumes concern the citizens, but several additional volumes cover the visitors (‘forestieri’) and resident foreigners (‘dimoranti’). It is in these latter volumes that we find the Cerutis. Thanks to them we now know that Giuseppe Ceruti and his family arrived in Mantua in May 1838, remained until early 1851 and then left for San Benedetto Po, but did not appear to return to Cremona.

This is not to say that the Austrian records were fool-proof. We need only look at the entries in the registers for the Cerutis to see that accuracy was relative. Giuseppe’s entry describes him as the son of Giovanni Battista and Margherita ‘Bavelotti’ (the actual name is Bardelli), that he was born in Cremona in 1790 (more accurately in Sesto Cremonese in 1785) and that he was a maker of musical instruments. Accompanying him were his wife, Amalia Boccalari, their two daughters, Elisa and Clato, and Giuseppe’s mother, Margherita Bardelli. They lived briefly in several different lodgings before settling into a house on the western edge of the old city.

By 1840 they had gained residency; their entries in the dimoranti volume list their various homes for the subsequent decade. As in the earlier entries, there is a predictable quantity of mangled names and birth dates, but the basic information leaves no ambiguity as to their identities. By this date Giuseppe’s profession was recorded as a maker of geometric instruments, a nod to his long-standing interest in mechanical devices. In other documents he was referred to as a maker of geodetic instruments and simply as a mechanic, which was how he was described in 1848, when he patented a device for turning the pages of music on a piano.

Along with Giuseppe in the dimoranti volume was his wife, this time called Amalia ‘Bacchetta’ (this was her mother’s family name), their two daughters, and a surprise visitor: Amalia Ceruti, Enrico’s daughter and Giuseppe’s granddaughter. She remained with the family until around 1843.

Along with Giuseppe in the dimoranti volume… was a surprise visitor: Amalia Ceruti, Enrico’s daughter and Giuseppe’s granddaughter

In 1844 the one and only municipal trades directory published in Mantua during these years finally came to print after a long gestation (the title page is dated 1838). Under the listings of makers of musical instruments we find three that we can connect to the stringed instrument profession. First on the list is Sante Coppi, a successful businessman and Giuseppe Dall’Aglio’s brother-in-law, whose work is known today by a bare handful of instruments. The next name listed is that of Giuseppe Ceruti. He occupied a rented shop on the via S. Silvestro, near to the Teatro Sociale, the principal concert venue of that time, and lived in a separate house not far away. The last familiar name on our list is ‘Dalai’, a reference to Giuseppe Dall’Aglio, who was known by this dialect name for much of his life.

Through much of the 1840s the Cerutis lived in the Parish of S. Barnaba, south of the central business district and in the direction of the modern railway station. It was here that Amalia Boccalari died in June 1849. Many of the houses in this district were rented, resulting in some interesting but ultimately insignificant coincidences. For example, at one time Ceruti lived in the same house as Gaetano Antoniazzi, but these events were separated by a decade. Similarly, several of his homes were close to those once occupied by Dall’Aglio, but the two were never resident there at the same time.

The Cerutis’ residency in S. Barnaba is, however, significant in that this was also the home of Pietro Bignami, a notary from San Benedetto Po who also maintained an office in Mantua. Presumably this proximity allowed an opportunity for him to meet Clato Ceruti, whom he married in the Church of S. Barnaba in October 1850. However, from 1851 the entire family, Bignamis and Cerutis combined, disappears from the Mantuan records for some years.

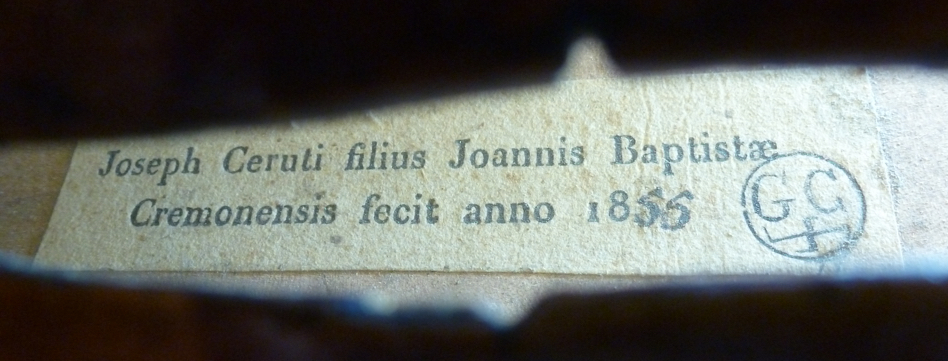

Ceruti label from the 1855 violin made in Mantua. Photo courtesy Jim Warren

There could well be a political dimension to this. As has been mentioned, the Austrians were increasingly uneasy about Italian sentiments among the residents, and not without reason. Just days before the Bignami–Ceruti wedding a group of ten conspirators had met in Mantua to organize a revolt. The broadsides and handbills printed by this group, as well as their active efforts at insurrection, came under Austrian scrutiny and in 1851 they began a campaign to put it down and arrest the conspirators. Eventually 110 people were arrested and twelve of them, including the priest Enrico Tazzoli who had been one of the ringleaders, were executed in the nearby town of Belfiore.

Whenever one examines the history of the quest for Italian Unification, the town of San Benedetto Po appears, for it was a principal center for the conspirators. However, during this period, perhaps because its civic leadership was connected to the conspiracies, it did not suffer the reprisals that the Austrians wrought upon Mantua. So perhaps it was a safe haven for the extended family of Pietro Bignami, who appears to have moved back there in 1851 and not returned to Mantua until 1856, long after the insurrection had run its course.

Perhaps the town of San Benedetto Po was a safe haven for the extended Ceruti–Bignami family

While we cannot say with absolute certainty that Giuseppe Ceruti was in San Benedetto at this point, there is no reason to think that he, now an elderly widower, was not living with his daughter and her family. Indeed, when he was preparing to enter two violins in the Paris Exposition of 1855, the papers in Mantua mentioned this fact, describing him as a violin maker from San Benedetto; his entry in the Paris Exposition competitor listing also refers to him as being from San Benedetto.

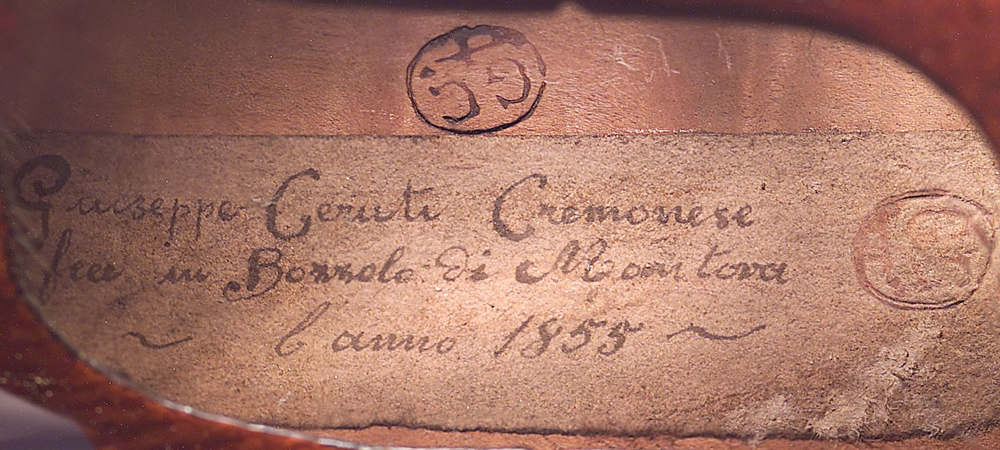

Ceruti manuscript label from Bozzolo, a town near Mantua. Photo courtesy Jim Warren

When the Bignamis did return to the city Giuseppe came along and for the rest of his life he is recorded as living with his daughter and son-in-law, first in houses in San Barnaba and finally in a house close to the Monastery of San Francesco. It was here that he died on August 31, 1860.

Of course our chief interest in Giuseppe Ceruti is not his life or political affiliations, but rather the stringed instruments he created. Giuseppe was certainly far less productive than either his father, Giovanni Battista, or his son Enrico, but these recent archival discoveries suggest that we need to revise our ideas about his later output. Apart from one violin bearing a handwritten label from Bozzolo, a town in the territory of Mantua, we do not see instruments specifically labeled from Mantua. However, we have probably been seeing them all along and simply not realizing it. Like many earlier makers, Ceruti described his origins as ‘Cremonese’ on his labels but then did not identify in which town he made them. Origins could be revealed here in the form of wood selections and the types of varnishes and models adopted. The entire subject, therefore, is open for renewed attention.

Expert and violin historian Philip J. Kass has contributed extensively to the Journal of the Violin Society of America, The Strad magazine and the New Grove Dictionary of Music among other publications.